| Total population | |

|---|---|

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Belgrade, Beočin, Bojnik, Nova Crnja, Žitorađa | |

| [1][2] | |

| Languages | |

| Balkan Romani, Serbian, Romano-Serbian, Romanian, Albanian, Hungarian | |

| Religion | |

| Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Sunni Islam, Roman Catholic |

Romani people, or Roma (Serbian: Роми, romanized: Romi), are the fourth largest ethnic group in Serbia, numbering 131,936 (1.98%) according to the 2022 census. However, due to a legacy of poor birth registration and some other factors, this official number is likely underestimated.[3][4] Estimates that correct for undercounting suggest that Serbia is one of countries with the most significant populations of Roma people in Europe at 250,000-500,000. Anywhere between 46,000[5] to 97,000[6] Roma are internally displaced from Kosovo after 1999.

Another name used for the community is Cigani (Serbian Cyrillic: Цигани), although the term is today considered pejorative and is not officially used in public documents. They are divided into numerous subgroups, with different, although related, Romani dialects and history.

Subgroups

As there are difficulties with the data collection, historization, and with the questionable familiarity of the Serbian scholars with Roma lives and culture and significant demographic changes and migrations of Roma population, it is difficult to establish one definite division within Roma community. According to the study of scholar Tihomir Đorđević (1868–1944),[7] main sub-groups include "Turkish Gypsies" (Turski Cigani), "White Gypsies" (Beli Cigani), "Wallachian Gypsies" (Vlaški Cigani) and "Hungarian Gypsies" (Mađarski Cigani).

- Wallachian Roma. Migrated from Romania, through Banat.[8] They have converted to Eastern Orthodoxy and mostly speak Serbian fluently.[9] They are related to the Turkish Roma.[8] T. Đorđević noted several sub-groups.[10]

- Turkish Roma, also known as Arlia. Migrated from Turkey.[11] At the beginning of the 19th century the Turkish Roma lived mainly in southeastern Serbia, in what was the Sanjak of Niš.[12] The Serbian government attempted to force Orthodoxy on them after the conquest of the sanjak (1878), but without particular success.[12] They are mainly Muslims.[12] T. Đorđević noted an internal division between old settlers and new settlers, who had differing traditions, speech, family organization and occupations.[7]

- "White Gypsies", arrived later than other Romani groups, at the end of the 19th century,[8] from Bosnia and Herzegovina.[11] Permanently settled mostly in towns.[8] Serbian-speakers.[8] Sub-group of Turkish Roma.[8] T. Đorđević noted them as living in Podrinje and Mačva, being Muslim, and that they had lost their language.[7]

- Hungarian Roma.

History

Research on Roma migrations is scarce. Roma often lived on the margins and their presence was often not registered in documents so it is difficult to claim any definite historical path of Roma. On some accounts, Roma arrived in Serbia in several waves.[13] The first reference to Roma in Serbia is found in a 1348 document, by which Serbian emperor Stefan Dušan donated some Roma slaves to a monastery in Prizren.[14] In the 15th century, Romani migrations from Hungary are mentioned.[13]

In 1927, a Serbian-Romani humanitarian organization was founded.[15] In 1928, a Romani singing society was founded in Niš.[15] In 1932, a Romani football club was founded.[15] In 1935, a Belgrade student established the first Romani magazine, Romani Lil, and in the same year a Belgrade Romani association was founded.[15] In 1938, an educational organization of Yugoslav Romani was founded.[15]

Culture

The Romani people in Central Serbia are predominantly Eastern Orthodox but a minority of Muslim Romani exists (notably recent refugees from Kosovo), mainly in the southern parts of Serbia. Romani people in multi-ethnic Vojvodina are integrated with other ethnic groups, especially with Serbs, Romanians and Hungarians. For this reason, depending on the group with which they are integrated, Romani are usually referred to as Serbian Romani, Romanian Romani, Hungarian Romani, etc.

The majority of Romani people are Christian and a minority are Muslim. They speak mainly Romani and Serbian. Some also speak the language of other people they have been influenced by: Romanian, Hungarian or Albanian. Đurđevdan (or Ederlezi) is a traditional feast day of Romani in Serbia. In October 2005 the first text on the grammar of the Romani language in Serbia was published by linguist Rajko Đurić, titled Gramatika e Rromane čhibaki - Граматика ромског језика.

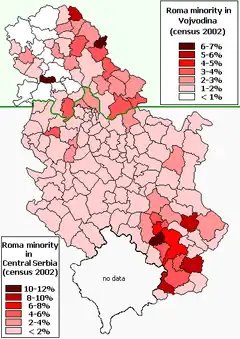

Demographics

.PNG.webp)

There are 131,936 Romani people in Serbia, but unofficial estimates put the figure up to 450,000-550,000.[16] Between 23,000-100,000 Serbian Roma are internally displaced persons from Kosovo.[5][6]

| Census | Population | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1866 | 24,607 | |

| 1895 | 46,000 | |

| 1921 | 34,919 | Analysis of census (including SR Serbia and SR Macedonia).[10] |

| 1948 | 52,181 | |

| 1953 | 58,800 | |

| 1961 | 9,826 | |

| 1971 | 49,894 | |

| 1981 | 110,959 | |

| 1991 | 94,492 | |

| 2002 | 108,193 | |

| 2011 | 147,604 | |

| 2022 | 131,936 |

Discrimination

A large number of Serbian Roma people live in segregated areas, often in slums with houses of different quality,[17][18] some in so-called "cardboard cities" without electricity or water or provision of public services. On 3 April 2009, a group of Romani people who had been living in an unlawful settlement in Novi Beograd were evicted on the orders of the mayor of Belgrade. According to the press, bulldozers accompanied by police officers arrived to clear the site early in the morning before the formal eviction notice was presented to the community. The makeshift dwellings were torn apart while their former occupants watched. The site was cleared in order to make way for an access road to the site of the 2009 Student Games, to be held in Belgrade later this year. Temporary alternative accommodation in the form of containers had apparently been provided by the Mayor of Belgrade, but some 50 residents of the suburb where they had been located attempted to set fire to three of the containers. Many of the evicted Roma have spent five nights sleeping in the open in the absence of any alternative accommodation.[19] There have been incidents of FK Rad hooligan (and skinhead) attacks on Roma, such as the death of thirteen-year-old Dušan Jovanović (1997),[20] and also the death of actor Dragan Maksimović, who was assumed to be Romani (2001).[21]

Due to a record of discrimination, human rights reporting mechanisms have consistently drawn attention to the treatment of the Romani people in Serbia.[22][23] The United Nations have reported persistent discrimination and social exclusion as a concern, particularly stemming from poor birth registration and identity documentation for citizens, and inequitable access to education, housing, employment, and legal protections.[22] The UN has expressed concerns that the state of Serbia has failed to ensure accountability measures that continually monitor and implement these rights.

These persistent challenges cause many Roma to flee Serbia and other Balkan countries for EU countries. There are cases of Serbian children being granted refugee status in Ireland due to persecution due to Roma identity.[24] However, with increasingly strict asylum measures in the EU, countries such as Germany are increasingly labeling Serbia and other Balkan countries as “safe countries of origin” despite a lack of measurable improvement in the ability of Roma groups to realize human rights in these countries.[25][26]

Religion

According to the 2011 Census, most Roma in Serbia are Christians (62.7%). A majority belong to the Eastern Orthodox Church (55.9%), followed by Catholics (3.3%) and various Protestant churches (2.5%). There is also a significant Muslim Roma community living in Serbia, with 24.8% of all Roma being Muslim. A large part of the Roma people did not declare their religion.[27]

Political parties

Notable people

- Rajko Đurić, professor, journalist, and politician

- Srđan Šajn, politician

- Boban Marković, trumpeter

- Fejat Sejdić, trumpeter

- Janika Balaž, tamburitza musician

- Šaban Bajramović, folk and jazz singer

- Džej Ramadanovski, folk singer

- Sinan Sakić, folk singer

- Hasan Dudić, folk singer and former boxer

- Usnija Redžepova, folk singer

- Mina Kostić, pop singer

- Predrag Luka, footballer

- Dejan Osmanović, footballer

- Ahmed Ademović, soldier

- Vida Pavlović, folk singer

See also

Notes

- ↑ This is a census figure. Some 368,136 (5.1% of the population) did not declare any ethnicity. There was not any option for a person to declare multiple ethnicities.

References

- ↑ Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији: Национална припадност [Census of population, households and apartments in 2011 in the Republic of Serbia: Ethnicity] (PDF) (in Serbian). State Statistical Service of the Republic of Serbia. 29 November 2012. p. 8. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "Serbia: Country Profile 2011–2012" (PDF). European Roma Rights Centre. p. 7. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "UNICEF Serbia - Real lives - Life in a day: connecting Roma communities to health services (and more)". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Roma: Discriminated in Serbia, unwanted in Germany | Germany | DW | 10.08.2015". DW.COM. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- 1 2 "EDUCATION OF ROMA CHILDREN as IDPs/RETURNEES". 1 January 2016. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - 1 2 Relief, UN (2010). "Roma in Serbia (excluding Kosovo) on 1st January 2009" (PDF). UN Relief. 8 (1).

- 1 2 3 IFDT 2005, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vlahović 2004, p. 67.

- ↑ Human Rights and Collective Identity: Serbia 2004. Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia. 1 January 2005. ISBN 978-86-7208-106-0.

- 1 2 IFDT 2005, p. 22.

- 1 2 Sait Balić (1989). Džanglimasko anglimasqo simpozium I Romani ćhib thaj kultura. Institut za proučavanje nacionalnih odnosa--Sarajevo. p. 53.

- 1 2 3 Adrian Marsh; Elin Strand (22 August 2006). Gypsies and the Problem of Identities: Contextual, Constructed and Contested. Swedish Research Institute in Istanbul. p. 180. ISBN 978-91-86884-17-8.

- 1 2 Vlahović 2004, p. 66.

- ↑ Djordjević , T.R. (1924). Iz Srbije Kneza Milosa. Stanovnistvo—naselja. Beograd: Geca Kon.

- 1 2 3 4 5 IFDT 2005, p. 23.

- ↑ "Roma in the Balkan context" (PDF). 13 January 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ↑ "Podstandardna romska naselja u Srbiji" (PDF). osce.org. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ↑ "Mapiranje podstandardnih romskih naselja SRB" (PDF). un.org. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ↑ "Everything you need to know about human rights. | Amnesty International". Amnesty.org. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "Smrt u državi nasilja". E-novine.com. 18 October 2012. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "14 GODINA OD SMRTI: Dragan Maksimović Maksa zaslužio da dobije svoju ulicu! – Opustise.rs". 4 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - 1 2 "OHCHR | Serbia Homepage". www.ohchr.org. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ "Serbia/Kosovo". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ Child Migration and Human Rights in a Global Age. Bhabha, Jacqueline. New Jersey: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS. 2016. ISBN 978-0691169101. OCLC 950746587.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "Germany's a Dream for Serbia's Roma Returnees :: Balkan Insight". www.balkaninsight.com. 22 October 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ "Germany: Roma march against asylum-seeker crackdown". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ↑ "Population by national affiliation and religion, Census 2011". Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

Sources

- Vlahović, Petar (2004). Serbia: the country, people, life, customs. Ethnographic Museum. ISBN 978-86-7891-031-9.

- IFDT (2005). Umetnost preživljavanja: gde i kako žive Romi u Srbiji. IFDT. ISBN 978-86-17-13148-5.

Further reading

- Rajko Đurić; Václav Havel (2006). Istorija Roma: (pre i posle Aušvica). Politika. ISBN 978-86-7607-084-8.

- Biljana Sikimić (2005). Banjaši na Balkanu: identitet etničke zajednice. Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti, Balkanološki Institut. ISBN 9788671790482.

- Dragoljub Acković (2009). Romi u Beogradu: istorija, kultura i tradicija Roma u Beogradu od naseljavanja do kraja XX veka. Rominterpres. ISBN 978-86-7561-095-3.

- Zlata Vuksanović-Macura; Vladimir Macura (2007). Stanovanje i naselja Roma u jugoistočnoj Evropi: prikaz stanja i napretka u Srbiji. Društvo za Unapređivanje Romskih Naselja. ISBN 978-86-904327-2-1.

- Roma in Serbia. Fond za humanitarno pravo. 2003. ISBN 978-86-82599-45-6.