| Romance comics | |

|---|---|

| |

| Authors | |

| Publishers | |

| Publications |

|

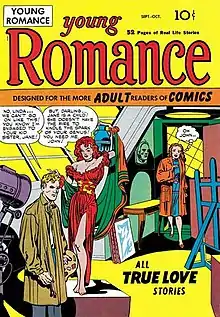

Romance comics are a genre of comic books that were most popular during the Golden Age of Comics. The market for comics, which had been growing rapidly throughout the 1940s, began to plummet after the end of World War II when military contracts to provide disposable reading matter to servicemen ended. This left many comic creators seeking new markets. The romance comic genre was created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, who kicked off Young Romance in 1947 in an effort to tap into new adult audiences. In the next 30 years, over 200 issues of the flagship romance comic would be produced.[1]

History

As World War II ended the popularity of the superhero comics diminished, and in an effort to retain readers comic publishers began diversifying more than ever into such genres as war, Western, science fiction, crime, horror and romance comics.[2] The genre took its immediate inspiration from the romance pulps; confession magazines such as True Story; radio soap operas, and newspaper comic strips that focused on love, domestic strife, and heartache, such as Rex Morgan, M.D. and Mary Worth.[3] Teen humor comics had romantic plots before the invention of romance comics.[1]

By 1950, more than 150 romance titles were on the newsstands from Quality Comics, Avon, Lev Gleason Publications, and DC Comics. The DC Comics romance line was overseen by Jack Miller, who also wrote many stories.[4] Fox Feature Syndicate published over two dozen love comics with 17 featuring "My" in the title—My Desire, My Secret, My Secret Affair, et al.[3]

Charlton Comics published a wide line of romance titles, particularly after 1953 when it acquired the Fawcett Comics line, which included Sweethearts, Romantic Secrets, and Romantic Story. Sweethearts was the comics world's first monthly romance title[5] (debuting in 1948), and Charlton continued publishing it until 1973.

Artists working romance comics during the period included Matt Baker, Frank Frazetta, Everett Kinstler, Jay Scott Pike, John Prentice, John Romita, Sr., Leonard Starr, Alex Toth, and Wally Wood.[6]

Decline and Golden Age demise

Following the implementation of the Comics Code in 1954, publishers of romance comics self-censored the content of their publications, making the stories bland and innocent with the emphasis on traditional patriarchial concepts of women's behavior, gender roles, domesticity, and marriage. When the sexual revolution questioned the values promoted in romance comics, along with the decline in comics in general, romance comics began their slow fade. DC Comics, Marvel Comics and Charlton Comics carried a few romance titles into the middle 1970s, but the genre never regained the level of popularity it once enjoyed. The heyday of romance comics came to an end with the last issues of Young Romance and Young Love in the middle 1970s.[5][6][7]

Charlton and DC artist and editor Dick Giordano stated in 2005:

[G]irls simply outgrew romance comics ... [The content was] too tame for the more sophisticated, sexually liberated, women's libbers [who] were able to see nudity, strong sexual content, and life the way it really was in other media. Hand-holding and pining after the cute boy on the football team just didn't do it anymore, and the Comics Code wouldn't pass anything that truly resembled real-life relationships."[5]

Decades later, romance-themed comics made a modest resurgence with Arrow Publications' "My Romance Stories",[8] Dark Horse Comics' manga-style adaptations of Harlequin novels,[9][10] and long-running serials such as Strangers in Paradise — described by one reviewer as an attempt "to single-handedly update an entire genre with a new, skewed look at relationships and friendships."[11]

In popular culture

Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein derived many of his best-known works from the panels of romance comics:

- Drowning Girl (1963) — Lichtenstein adapted the splash page from "Run for Love!", illustrated by Tony Abruzzo and lettered by Ira Schnapp, in Secret Hearts 83 (DC Comics, November 1962)[12][13][14]

- Hopeless (1963) — adapted from a panel from the same story, "Run for Love!", artwork by Tony Abruzzo and lettered by Ira Schnapp, in Secret Hearts 83 (November 1962)[15]

- Crying Girl (1963) — adapted from "Escape from Loneliness," pencilled by Tony Abruzzo[16] and inked by Bernard Sachs,[17] in Secret Hearts 88 (DC Comics, June 1963)

- Ohhh...Alright... (1964) — also derived from Secret Hearts 88 (June 1963)[18]

- In the Car (sometimes called Driving) (1963) — adapted from a Tony Abruzzo[19] panel in Girls' Romances 78 (DC, September 1961)

- We Rose Up Slowly (1964) — based on a panel from Girls' Romances 81 (January 1962)

- Sleeping Girl (1964) — based on a Tony Abruzzo[20] panel from Girls' Romances 105 (October 1964).[21]

Notable romance comics

| Title | Publisher | Issues | Publ. dates | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Date with Judy | DC | 79 | 1947–1960 | Combined romance with humor |

| Falling in Love | DC | 143 | 1955–1973 | |

| First Love Illustrated | Harvey | 90 | 1949–1963 | Harvey's only notable romance comic |

| Girls' Love Stories | DC | 180 | 1949–1973 | |

| Girls' Romances | DC | 160 | 1950–1971 | |

| Heart Throbs | Quality/ DC | 146 | 1949–1972 | Acquired from Quality in 1957 |

| I Love You | Charlton | 124 | 1955-1980 | |

| Just Married | Charlton | 114 | 1958-1976 | |

| Love Diary | Charlton | 102 | 1958-1976 | |

| Love Romances | Marvel | 101 | 1949-1963 | |

| Lovelorn/ Confessions of the Lovelorn | American | 114 | 1949-1960 | |

| Millie the Model | Marvel | 207 | 1945-1973 | Ostensibly a humor title; only a true romance comic from 1963–1967 |

| My Date Comics | Hillman | 4 | 1947-1948 | Simon & Kirby; first humor-romance comic |

| My Life True Stories in Pictures | Fox | 12 | 1948-1950 | Fox's longest-running romance comic — the only one of the company's 17 romance series with the word "My" in the title to last more than 8 issues |

| Patsy Walker | Marvel | 124 | 1945-1965 | Ostensibly a humor title; only a true romance comic in 1964–1965 |

| Romantic Adventures/ My Romantic Adventures | American | 138 | 1949–1964 | |

| Romantic Secrets | Fawcett/ Charlton | 87 | 1949–1964 | Acquired from Fawcett in 1953 |

| Romantic Story | Fawcett/ Charlton | 130 | 1949–1973 | Acquired from Fawcett in 1954 |

| Secret Hearts | DC | 153 | 1949–1971 | Issue #83 was borrowed by Roy Lichtenstein for the Drowning Girl painting |

| Strangers in Paradise | Abstract Studio | 106 | 1994-2007 | |

| Superman's Girl Friend, Lois Lane | DC | 137 | 1958–1974 | Ditched the romance angle by c. 1970; eventually merged into The Superman Family |

| Sweethearts | Fawcett/ Charlton | 170 | 1948-1973 | First monthly romance comic; acquired from Fawcett in 1954 |

| Teen Confessions | Charlton | 97 | 1959-1976 | |

| Teen-Age Romances | St. John | 45 | 1949-1955 | |

| Teen-Age Love | Charlton | 93 | 1958-1973 | |

| Young Love | Crestwood/ DC | 199 | 1947–1977 | Acquired from Crestwood in 1963 |

| Young Romance | Crestwood/ DC | 208 | 1947–1975 | Generally considered the first romance comic, created by Simon & Kirby. Acquired from Crestwood in 1963 |

Reprints

Comics historian John Benson collected and analyzed St. John Publications' romance comics in Romance Without Tears (Fantagraphics, 2003), focusing on the elusive comics scripter Dana Dutch, and the companion volume Confessions, Romances, Secrets and Temptations: Archer St. John and the St. John Romance Comics (Fantagraphics, 2007). To research the 1950s era of romance comics, Benson interviewed Ric Estrada, Joe Kubert and Leonard Starr, plus several St. John staffers, including editor Irwin Stein, production artist Warren Kremer and editorial assistant Nadine King.

In 2011, an anthology Agonizing Love: The Golden Era of Romance Comics, edited by Michael Barson, was published by Harper Design. In 2012, many of Simon and Kirby's romance comics were reprinted by Fantagraphics in a collection entitled Young Romance: The Best of Simon & Kirby's 1940s-'50s Romance Comics, edited by Michel Gagné.

British romance comics

Romance comics in the United Kingdom also flourished in the mid-1950s with such weekly titles as Mirabelle (Pearson), Picture Romances (Newnes/IPC), Valentine (Amalgamated Press), and Romeo (DC Thomson). All four titles lasted into the 1970s. Other British romance comics included Marilyn (1955–1965), New Glamour (1956–1958), Roxy (1958–1963), Marty (1960–1963), and Serenade (1962–1963); all of which eventually merged into Valentine and Mirabelle (Valentine itself merged into Mirabelle in 1974).[lower-alpha 1]

In 1956–1957 DC Thomson launched a line of monthly romance titles: Blue Rosette Romances, Golden Heart Love Stories, Love & Life Library, and Silver Moon Romances. In April 1965, all four titles were merged into the single weekly Star Love Stories title, with one issue per month maintaining the cover logo from the original companion titles.[23] Star Love Stories, which changed its name to Star Love Stories in Pictures in 1976, lasted until 1990.[24]

The photo comic romance titles Photo Love and Photo Secret debuted in 1979 and 1980 respectively. They both eventually merged into another publication.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ In contrast to romance comics, which were aimed at older teens and young women, the prevalent form of UK comics marketed to females were girls' comics, geared toward younger teens, which also flourished during this period. These weekly comics developed more of a romance angle in the 1980s.[22]

Citations

- 1 2 Mitchell, Claudia A.; Jacqueline Reid-Walsh (2008). Girl Culture. Greenwood Press. pp. 508–509. ISBN 978-0-313-33908-0.

- ↑ Kovacs, George; Marshall, C. W., eds. (2011). Classics and Comics. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 109. ISBN 978-0199734191.

- 1 2 Goulart, Ron (2001). Great American Comic Books. Publications International, Ltd. pp. 161, 169–172. ISBN 0-7853-5590-1.

- ↑ The Comic Reader #77 (Jan. 1970).

- 1 2 3 Nolan, Michelle (2008). Love on the Racks: A History of American Romance Comics. McFarland & Company, Inc. pp. 30, 210. ISBN 978-0-7864-3519-7.

- 1 2 "Profiles: Romance Comics". The Quarter Bin. January 7, 2001. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ↑ Miller, Jenny (2001). "A Very Brief History of Romance Comics". Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Arrow Publications Presents: MyRomanceStory". Arrow Publications LLC. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Press Releases: Harlequin Ginger Blossom Manga". Dark Horse Comics, Inc. May 16, 2005. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ↑ Glazer, Sarah (September 18, 2005). "Manga for Girls". The New York Times. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Cold Cut Distribution Reviews 13 - March 1996". Coldcut.com. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ↑ Tony Abruzzo (a), Ira Schnapp (let). "Run for Love!" Secret Hearts, no. 83, p. 1 (November 1963). DC Comics.

- ↑ Waldman, Diane (1993). Roy Lichtenstein. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. pp. 118–119. ISBN 0-89207-108-7.

- ↑ Arntson, Amy E (2006). Graphic Design Basics. Cengage Learning. p. 165. ISBN 0-495-00693-9.

- ↑ "Secret Hearts 83 (a)". Lichtenstein Foundation. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ↑ "Secret Hearts #88". Grand Comics Database. June 1963. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- ↑ Secret Hearts 88 (DC Comics, June 1963)

- ↑ "Ohhh...Alright..." Lichtenstein Foundation. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ↑ Barsalou, David (2000). "In the Car". Deconstructing Roy Lichtenstein. Retrieved September 14, 2020 – via Flickr.

- ↑ Barsalou, David (5 September 2000). "Sleeping Girl". Deconstructing Roy Lichtenstein (2000). Retrieved September 14, 2020 – via Flickr.

- ↑ "Sleeping Girl". Lichtenstein Foundation. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ↑ Newson, Kezia (2014). How Has The Pre–teen Girls' Magazine Influenced Girls From The 1950s To Present Day?. p. 6. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- ↑ "Star Love Stories," Grand Comics Database. Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ↑ Star Love Stories in Pictures entry, Grand Comics Database. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

External links

- Young Romance at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on December 18, 2011.

- "Classic Good Girl and Romance". SamuelDesign.com (fan site). Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

- Sequential Crush, a blog "devoted to preserving the memory of romance comic books and the creative teams that published them throughout the 1960s and 1970s"