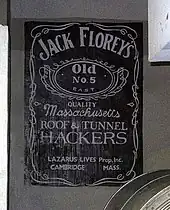

Roof and tunnel hacking is the unauthorized exploration of roof and utility tunnel spaces.[1] The term carries a strong collegiate connotation, stemming from its use at MIT and at the U.S. Naval Academy, where the practice has a long history. It is a form of urban exploration.

Some participants use it as a means of carrying out collegiate pranks, by hanging banners from high places or, in one notable example from MIT, placing a life-size model police car on top of a university building.[2] Others are interested in exploring inaccessible and seldom-seen places; that such exploration is unauthorized is often part of the thrill. Roofers, in particular, may be interested in the skyline views from the highest points on a campus.

On August 1, 2016, Red Bull TV launched the documentary series URBEX – Enter At Your Own Risk, which also chronicles roof and tunnel hacking.

Vadding

Vadding is a verb which has become synonymous with urban exploration. The word comes from MIT where, for a time in the late 1970s, some of the student population was addicted to a computer game called ADVENT (also known as Colossal Cave Adventure). In an attempt to hide the game from system administrators who would delete it if found, the game file was renamed ADV. As the system administrators became aware of this, the filename was changed again, this time to the permutation VAD. The verb vad appeared, meaning to play the game. Likewise, vadders were people who spent a lot of time playing the game.

Thus, vadding and vadders began to refer to people who undertook actions in real life similar to those in the game. Since ADVENT was all about exploring tunnels, the MIT sport of roof and tunnel hacking became known as vadding.

Today, the word vadding is rarely used at MIT (usually only by old-timers) and roof and tunnel hacking has returned as the preferred descriptive term. Those who participate in it generally refer to it simply as "hacking".

Roof hacking

Many buildings at American universities have flat roofs, whereas pitched roofs designed to shed snow or heavy rain present safety challenges for roof hackers. Entry points, such as trapdoors, exterior ladders, and elevators to penthouses that open onto roofs, are usually tightly secured. Roofers bypass locks (by lock picking or other methods), or use unsecured entry points to gain access to roofs. Once there, explorers may take photographs or enjoy the view; pranksters may hang banners or execute other sorts of mischief.

Bell towers in some colleges are also prone to being a target for rooftopers.

Tunnel hacking

Some universities have utility tunnels to carry steam heat and other utilities. Utility tunnels are usually designed for infrequent access for maintenance and the installation of new utilities, so they tend to be small and often cramped. Sometimes, utilities are routed through much larger pedestrian access tunnels (MIT has a number of such tunnels, reducing the need for large networks of steam tunnels; for this reason, there is only one traditional steam tunnel at MIT, built before many buildings were connected).

Tunnels range from cold, damp, and muddy to unbearably hot (especially during cold weather). Some are large enough to allow a person to walk freely; others are low-ceilinged, forcing explorers to stoop, bend their knees, or even crawl. Even large tunnels may have points where crisscrossing pipes force an explorer to crawl under or climb over a pipe—a highly dangerous activity, especially when the pipe contains scalding high-pressure steam (and may not be particularly well insulated, or may have weakened over the years since installation).

Tunnels also tend to be loud. Background noise may prevent an explorer from hearing another person in the tunnel—who might be a fellow explorer, a police officer, or a homeless person sheltering there. Tunnels may be well lit or pitch-dark, and the same tunnel may have sections of both.

Tunnel access points tend to be in locked mechanical rooms where steam pipes and other utilities enter a building, and through manholes. As with roofs, explorers bypass locks to enter mechanical rooms and the connected tunnels. Some adventurers may open manholes from above with crowbars or specialized manhole-opening hooks.

Shafting

Buildings may have maintenance shafts for passage of pipes and ducts between floors. Climbing these shafts is known as shafting. The practice is similar to buildering, which is done on the outsides of buildings.

Regular use of a shaft can wear down insulation and cause other problems. To fix these problems, hackers sometimes take special trips into the shafts to correct any problems with duct tape or other equipment.

A dangerous variant of shafting involves entering elevator shafts, either to ride on the top of the elevators, or to explore the shaft itself. This activity is sometimes called elevator surfing. The elevator is first switched to "manual" mode, before boarding or exiting, and back to "automatic" mode after, to allow normal operation (and avoid detection). Switching elevators, getting too near the ceiling (or under the elevator) or the counterweight (or cables), or otherwise failing to follow safety precautions can lead to death or injury. Crackdowns may increase in both frequency and harshness, both legally and with respect to physical access to coveted locations.

Some shafts (such as those intended for but lacking an elevator) are accessible by use of rope but are not actually climbable by themselves.

Dangers

Legal dangers

Universities generally prohibit roof and tunnel hacking, either by explicit policies or blanket rules against entry into non-public utility spaces. The reasoning behind these policies generally stems from concern for university infrastructure and concern for students. Consequences vary from university to university; those caught may be warned, fined, officially reprimanded, suspended, or expelled. Depending on the circumstances, tunnelers and roofers may be charged with trespassing, breaking and entering, or other criminal charges.

MIT, once a vanguard of roof and tunnel hacking (books have been published on hacks and hacking at MIT), has been cracking down on the activity. In October 2006, three students were caught hacking near a crawl space in the MIT Faculty Club, arrested by the MIT police, and later charged with trespassing, breaking and entering with the intent to commit a felony.[3] The charges raised an outcry among students and alumni who believed that MIT ought to have continued its history of handling hacking-related incidents internally.[4]

Charges against those students were eventually dropped. In June 2008, another graduate student was arrested and faced charges of breaking and entering with intent to commit a felony and possession of burglarious instruments after being caught after-hours in a caged room in a research building's basement.[5]

Risks to building infrastructure

Utility tunnels carry everything from drinking water to power to fiber-optic network cabling. Some roofs have high power radio broadcast or radio reception equipment and weather-surveillance equipment, damage to which can be costly. Roofs and tunnels also may contain switches, valves, and controls for utility systems that were not designed to be accessible to the general public.

Due to security concerns there has been a trend towards installing intrusion alarms to protect particularly hazardous or high-value equipment.

Personal hazards

Roofs are dangerous; aside from the obvious risk of toppling over the edge (especially at night, in inclement weather, or after drinking) students could be injured by high-voltage cabling or by microwave radiation from roof-mounted equipment.[6] In addition, laboratory buildings often vent hazardous gasses through exhaust stacks on the roof.

Tunnels can be extremely dangerous—superheated steam pipes are not always completely insulated; when they are insulated, it is occasionally with carcinogenic materials like asbestos. Opening or damaging a steam valve or pipe can be potentially deadly. Steam contains significantly more thermal energy than boiling water, and transfers that energy when it condenses on solid objects such as skin. It is typically provided under high pressure, meaning that comparatively minor pipe damage can fill a tunnel with steam quickly. In 2008, a high-pressure steam pipe exploded in the subbasement of Building 66 at MIT, apparently due to a construction defect. The explosion and ensuing flood caused extensive damage and lethal conditions in the subbasement.[7]

Confined spaces contain a range of hazards—from toxic gases like hydrogen sulfide and carbon monoxide, to structures that may flood or entrap an adventurer. An explorer who enters a tunnel via a lock bypass method or via an inadvertently-left-open door may find themself trapped if the door locks behind them—quite possibly in an area with no cell phone reception, and no one within earshot.

See also

References

- ↑ Ninjalicious (2005). Access All Areas: A User's Guide to the Art of Urban Exploration. Infilpress. p. 223. ISBN 9780973778700. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ↑ "CP Car on the Great Dome". Retrieved 23 August 2010.

- ↑ Wang, Angeline (16 February 2007). "Three Students Face Felony Charges After Tripping E52 Alarm". The Tech. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ↑ Wang, Angeline (5 February 2008). "Hacking Tradition Under Fire?". The Tech. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ↑ Chu, Austin (13 June 2008). "Grad Student Found In NW16 Basement Faces Felony Charges". The Tech. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- ↑ Occupational Safety and Health Administration

- ↑ Guo, Jeff (4 November 2008). "Steam Pipe Explosion Damages Building 66". The Tech. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

External links

- MIT hacks site; deals primarily with pranks, some of which involve a roof hacking component

- Infiltration.org page on college tunnels

- Daily Princetonian article on a student injured in a fall while exploring a tower in the university's chapel

- UCSDSecrets, an introductory blog about UCSD. including its tunnels

- Institute Historian, T. F. Peterson, Nightwork: A History of Hacks and Pranks at MIT (revised edition), MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 2011. ISBN 978-0-262-51584-9—Extensive documentation, many photographs, special essays

- "Abandon Hope, Part 1" and "Abandon Hope, Part 2", a two-part article on the Columbia University tunnels