United States | |

| Value | 10 cents (0.10 U.S. dollar) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 2.268 g |

| Diameter | 17.91[1] mm (0.705 in) |

| Edge | reeded[2] |

| Composition | 1965-present: 75% Cu, 25% Ni clad over copper core 1946-64: 2.5 grams, 90% Ag and 10% Cu |

| Silver | Collectors' versions in silver. 1992-2018: 0.900 fine, 0.0803 troy oz From 2019: 0.999 fine, 0.082[2] troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1946 to present |

| Mint marks | P, D, S, W. Located from 1946 to 1964 on the lower reverse to the left of the torch, since 1968 on the obverse above the date. No mint mark used at Philadelphia before 1980 or at any mint from 1965 to 1967. |

| Obverse | |

| |

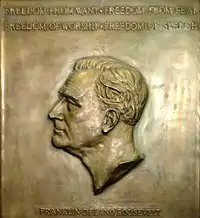

| Design | Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Designer | John R. Sinnock |

| Design date | 1946 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | Torch with branches of olive and oak |

| Designer | John R. Sinnock |

| Design date | 1946 |

The Roosevelt dime is the current dime, or ten-cent piece, of the United States. Struck by the United States Mint continuously since 1946, it displays President Franklin D. Roosevelt on the obverse and was authorized soon after his death in 1945.

Roosevelt had been stricken with polio, and was one of the moving forces of the March of Dimes. The ten-cent coin could be changed by the Mint without the need for congressional action, and officials moved quickly to replace the Mercury dime. Chief Engraver John R. Sinnock prepared models, but faced repeated criticism from the Commission of Fine Arts. He modified his design in response, and the coin went into circulation in January 1946.

Since its introduction, the Roosevelt dime has been struck continuously in large numbers. The Mint transitioned from striking the coin in silver to base metal in 1965, and the design remains essentially unaltered from when Sinnock created it. Without rare dates or silver content, the dime is less widely sought by coin collectors than other modern U.S. coins.

Inception and preparation

President Franklin D. Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, after leading the United States through much of the Great Depression and World War II. Roosevelt had suffered from polio since 1921 and had helped found and strongly supported the March of Dimes to fight that crippling disease, so the ten-cent piece was an obvious way of honoring a president popular for his war leadership.[3][4] On May 3, Louisiana Representative James Hobson Morrison introduced a bill for a Roosevelt dime.[5] On May 17, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. announced that the Mercury dime (also known as the Winged Liberty dime) would be replaced by a new coin depicting Roosevelt, to go into circulation about the end of the year.[6] Approximately 90 percent of the letters received by Stuart Mosher, editor of The Numismatist (the journal of the American Numismatic Association), were supportive of the change, but he himself was not, arguing that the Mercury design was beautiful and that the limited space on the dime would not do justice to Roosevelt; he advocated a commemorative silver dollar instead.[7] Others objected that despite his merits, Roosevelt had not earned a place alongside Washington, Jefferson and Lincoln, the only presidents honored on the circulating coinage to that point.[8] As the Mercury design, first coined in 1916, had been struck for at least 25 years, it could be changed under the law by the Bureau of the Mint. No congressional action was required, though the committees of each house with jurisdiction over the coinage were informed.[9]

Creating the new design was the responsibility of Chief Engraver John R. Sinnock, who had been in his position since 1925.[10] Much of the work in preparing the new coin was done by Sinnock's assistant, later chief engraver Gilroy Roberts.[11] In early October 1945, Sinnock submitted plaster models to Assistant Director of the Mint F. Leland Howard (then acting as director), who transmitted them to the Commission of Fine Arts. This commission reviews coin designs because it was tasked by a 1921 executive order by President Warren G. Harding with rendering advisory opinions on public artworks.[12]

The models initially submitted by Sinnock showed a bust of Roosevelt on the obverse and, on the reverse, a hand grasping a torch, and also clutching sprigs of olive and oak. Sinnock had prepared several other sketches for the reverse, including one flanking the torch with scrolls inscribed with the Four Freedoms. Other drafts showed representations of the goddess Liberty, and one commemorated the United Nations Conference of 1945, displaying the War Memorial Opera House where it took place.[13] Numismatist David Lange described most of the alternative designs as "weak".[14] The models were sent on October 12 by Howard to Gilmore Clarke, chairman of the commission, who consulted with its members and responded on the 22nd, rejecting them, stating that "the head of the late President Roosevelt, as portrayed by the models, is not good. It needs more dignity."[10] Sinnock had submitted an alternative reverse design similar to the eventual coin, with the hand omitted and the sprigs placed on either side of the torch; Clarke preferred this.[15]

Sinnock attended a conference at the home of Lee Lawrie, sculptor member of the commission, with a view to resolving the differences, and thereafter submitted a new model for the obverse, addressing the concerns about Roosevelt's head. The Mint Director, Nellie Tayloe Ross, sent photographs to the commission, which rejected it and proposed a competition among five artists, including Adolph A. Weinman (designer of the Mercury dime and Walking Liberty half dollar) and James Earle Fraser (who had sculpted the Buffalo nickel). Ross declined, as the Mint was under great pressure to have the new coins ready for the March of Dimes campaign in January 1946. The new Treasury Secretary, Fred Vinson, was appealed to, but he also disliked the models and rejected them near the end of December. Sinnock swapped the positions of the date and the word LIBERTY, allowing an enlargement of the head. He made other changes as well; according to numismatic author Don Taxay, "Roosevelt had never looked better!"[15]

Lawrie and Vinson approved the models. On January 8, Ross telephoned the commission, informing them of this. With Sinnock ill (he died in 1947) and the March of Dimes campaign under way, Ross did not wait for a full meeting of the commission, but authorized the start of production. This caused some ill-feeling between the Mint and the commission, but she believed that she had fulfilled her obligations under the executive order.[16]

Design

The obverse of the dime depicts President Roosevelt, with the inscriptions LIBERTY and IN GOD WE TRUST. Sinnock's initials, JS, are found by the cutoff of the bust, to the left of the date. The reverse shows a torch in the center, representing liberty, flanked by an olive sprig representing peace, and one of oak symbolizing strength and independence. The inscription E PLURIBUS UNUM (out of many, one) stretches across the field. The name of the country and the value of the coin are the legends that surround the reverse design,[17] which is symbolic of the victorious end of World War II.[4]

Numismatist Mark Benvenuto suggested that the image of Roosevelt on the coin is more natural than other such presidential portraits, resembling that on an art medal.[4] Walter Breen, in his comprehensive volume on U.S. coins, argued that "the new design was ... no improvement at all on Weinman's [Mercury dime] except for eliminating the fasces [on its reverse] and making the vegetation more recognizably an olive branch for peace."[18] Art historian Cornelius Vermeule called the Roosevelt dime "a clean, satisfying and modestly stylish, no-nonsense coin that in total view comes forth with notes of grandeur".[19]

Some, at the time of design and since, have seen similarities between the dime and a plaque depicting Roosevelt sculpted by African-American sculptor Selma Burke, unveiled in September 1945, which is in the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington; Burke was among those alleging her work was used by Sinnock to create the dime.[18] She advocated for this position until her death in 1994, and persuaded a number of numismatists and politicians, including Roosevelt's son James. Numismatists who support her point to the fact that Sinnock took his depiction of the Liberty Bell, which appears on the 1926 Sesquicentennial half dollar and Franklin half dollar (1948–1963), from another designer without giving credit. However, Robert R. Van Ryzin, in his book on mysteries about U.S. coins, pointed out that Sinnock had sketched Roosevelt from life in 1933 for his first presidential medal (designed by Sinnock), and accounts from the time of issuance of the dime state that Sinnock used those, as well as photographs of the president, to prepare the dime.[20] A 1956 obituary in The New York Times credits Marcel Sternberger with taking the photograph that Sinnock adapted for the dime.[21] According to Van Ryzin, the passage of time has made it impossible to verify or invalidate Burke's assertion. [22]

Production

The Roosevelt dime was first struck on January 19, 1946, at the Philadelphia Mint.[23] It was released into circulation on January 30, which would have been President Roosevelt's 64th birthday.[17] The planned release date had been February 5; it was moved up to coincide with the anniversary.[23] With its debut, Sinnock became the first chief engraver to be credited with the design of a new circulating U.S. coin since those designed by Charles E. Barber were first issued in 1892.[24] There were reports of the new dime being rejected in vending machines, but no changes to the coin were made.[23] The dime's design has not changed much in its over seventy years of production, the most significant alterations being minor changes to Roosevelt's hair and the shifting of the mint mark from reverse to obverse in the 1960s.[24]

At the time the dimes were released, relations with the USSR were deteriorating, and Sinnock's initials, JS, were deemed by some to refer to Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, placed there by a communist sympathizer. Once these rumors reached Congress, the Mint sent out press releases debunking this myth.[25][26] Despite the Mint's denial, there were rumors into the 1950s that there had been a secret deal at the Yalta Conference to honor Stalin on a U.S. coin.[23] The controversy was given fresh life in 1948 with the posthumous release of Sinnock's Franklin half dollar, which bears his initials JRS.[27]

Although usually more coins were struck at Philadelphia than at the other mints during the years the coin was struck in silver, only 12,450,181 were struck there in 1955, fewer than at the Denver Mint or at San Francisco. This was due to a sagging economy and a lackluster demand for coins that caused the Mint to announce in January that the San Francisco Mint would be shuttered at the end of the year. The 1955 dimes from the three facilities are the lowest mintages by date and mint mark among circulating coins in the series, but are not rare, as collectors stored them away in rolls of 50.[28]

With the Coinage Act of 1965, the Mint transitioned to striking clad coins, made from a sandwich of copper nickel around a core of pure copper. There are no mint marks on coins dated from 1965 to 1967, as the Mint made efforts to discourage the hoarding that it blamed for the coin shortages that had preceded the 1965 act.[29] The Mint modified the master hub only slightly when it began clad coinage, but starting in 1981, made minor changes that lowered the coin's relief considerably, leading to a flatter look to Roosevelt's profile. This was done so that coinage dies would last longer. Mint marks resumed in 1968 at Denver and for proof coins at San Francisco. Although the California facility beginning in 1965 occasionally struck dimes for commerce, those bore no mint marks and are indistinguishable from ones minted at Philadelphia.[30] The only dimes to bear the "S" mint mark for San Francisco since 1968 have been proof coins, resuming a series coined from 1946 to 1964 without mint mark at Philadelphia.[31] Starting in 1992, silver dimes with the pre-1965 composition were struck at San Francisco for inclusion in annual proof sets featuring silver coins.[32] Beginning in 2019, these silver dimes are struck in .999 silver, rather than .900, which the Mint no longer uses.[33]

In 1980, the Philadelphia Mint began using a mint mark "P" on dimes.[34] Dimes had been struck intermittently during the 1970s and 1980s at the West Point Mint, in Roosevelt's home state of New York, to meet demand, but none bore a "W" mint mark. This changed in 1996, when dimes were struck there for the 50th anniversary of the Roosevelt design. Just under a million and a half clad 1996-W dimes were minted; these were not released to circulation, but were included in the year's mint set for collectors. In 2015, silver dimes were struck at West Point for inclusion in a special set of coins for the March of Dimes, including a dime struck at Philadelphia and a silver dollar depicting Roosevelt and polio vaccine developer Dr. Jonas Salk.[35] Mintages generally remained high, with a billion coins each struck at Philadelphia and at Denver in many of the clad years.[36]

In 2003, Indiana Representative Mark Souder proposed that former president Ronald Reagan, who was then dying of Alzheimer's disease, replace Roosevelt on the dime once he died, stating that Reagan was as iconic to conservatives as Roosevelt was to liberals. Reagan's wife Nancy expressed her opposition, stating that she was certain the former president would not have favored it either. After Ronald Reagan died in 2004, there was support for a design change, but Souder declined to pursue his proposal.[37]

The Circulating Collectible Coin Redesign Act of 2020 (Pub. L. 116–330 (text) (PDF)) was signed by President Donald Trump on January 13, 2021. It provides for, among other things, special one-year designs for the circulating coinage in 2026, including the dime, for the United States Semiquincentennial (250th anniversary), with one of the designs to depict women.[38]

Collecting

Due to the large numbers struck, few regular-issue Roosevelt dimes command a premium, and the series has received relatively little attention from collectors. Though silver issues remain legal tender and can be removed from circulation and collected via coin roll hunting, clad coins form the majority of the dimes in circulation. Prominent among these are the dimes struck at Philadelphia in 1982, erroneously minted and released without the mint mark "P"; these may sell for $50 to $75. As no official mint sets were issued in 1982 or 1983, even ordinary dimes of those years from Philadelphia or Denver in pristine condition command a significant premium (worn ones do not). Far more expensive are the dimes erroneously issued in proof condition in 1970, 1975 and 1983 that lack the "S" mint mark. One of only two known from 1975 sold at auction in 2011 for $349,600.[24][39]

Citations

- ↑ "Dime". U.S. Mint. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- 1 2 Yeoman, p. 705.

- ↑ The Numismatist & November 1996, p. 1312.

- 1 2 3 The Numismatist & August 2003, p. 109.

- ↑ "A Roosevelt Dime Is Proposed" (PDF). The New York Times. May 4, 1945.

- ↑ The Numismatist & June 1945, p. 612.

- ↑ The Numismatist & July 1945, p. 732.

- ↑ Vermeule, p. 209.

- ↑ The Numismatist & June 1946, p. 646.

- 1 2 Taxay, p. 371.

- ↑ The Numismatist & November 1992, p. 1538.

- ↑ Taxay, pp. v–vi, 371.

- ↑ Vermeule, pp. 209–210.

- ↑ The Numismatist & August 2009, p. 21.

- 1 2 Taxay, pp. 371, 375.

- ↑ Taxay, p. 375.

- 1 2 The Numismatist & March 1946, p. 275.

- 1 2 Breen, p. 329.

- ↑ Vermeule, p. 208.

- ↑ Van Ryzin, pp. 189–213.

- ↑ "Marcel Sternberger; Photographer of Portrait for Roosevelt Dime Dead at 57". The New York Times. October 27, 1956.

- ↑ Van Ryzin, p. 213.

- 1 2 3 4 LaMarre, Tom (March 7, 2011). "Roosevelt on the Dime". Coins. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- 1 2 3 The Numismatist & March 2016, p. 32.

- ↑ Breen, pp. 329–330.

- ↑ Guth & Garrett, p. 64.

- ↑ Breen, p. 416.

- ↑ The Numismatist & January 2017, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Breen, p. 132.

- ↑ The Numismatist & November 1999, p. 1361.

- ↑ Yeoman, pp. 707–719.

- ↑ Yeoman, pp. 1265–1267.

- ↑ Gilkes, Paul (February 22, 2019). "U.S. Mint replaces 90 percent silver alloy with .999 fine silver". Coin World. Retrieved March 23, 2019.

- ↑ Breen, p. 332.

- ↑ The Numismatist & March 2016, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Yeoman, pp. 711–719.

- ↑ The Numismatist & March 2016, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Gilkes, Paul (January 15, 2021). "Circulating Collectible Coin Redesign Act of 2020 signed by president". Coin World. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ Yeoman, p. 713.

Sources

Books

- Breen, Walter (1988). Walter Breen's Complete Encyclopedia of U.S. and Colonial Coins. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-14207-6.

- Guth, Ron; Garrett, Jeff (2005). United States Coinage: A Study by Type. Atlanta, Georgia: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7948-1782-4.

- Taxay, Don (1983). The U.S. Mint and Coinage (reprint of 1966 ed.). New York: Sanford J. Durst Numismatic Publications. ISBN 978-0-915262-68-7.

- Van Ryzin, Robert R. (2009). Fascinating Facts, Mysteries & Myths About U.S. Coins. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. ISBN 978-1-4402-2764-6.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R. S. (2015). A Guide Book of United States Coins (1st Deluxe ed.). Atlanta, Georgia: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7948-4307-6.

Journals

- "New Dime to Honor Roosevelt". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 612. June 1945.

- "Let Well Enough Alone". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 732. July 1945.

- "Roosevelt Dime Put into Circulation". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 275. March 1946.

- Benvenuto, Mark A. (November 1996). "The Roosevelt Dime...a Half Century Later". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 1312.

- Brothers, Eric (January 2017). "1955: The End of an Era". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 51–55.

- Ganz, David L. (November 1992). "An Idea Whose Time Has Not Yet Come". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 1536–1546, 1611–1614.

- Lange, David W. (November 1999). "Grading Roosevelt Dimes". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 1361.

- Lange, David W. (August 2009). "A Look at the Roosevelt Dime". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 21–22.

- McMorrow-Hernandez, Joshua (March 2016). "The Roosevelt Dime Turns Seventy". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 30–35.

- Sanders, Mitch (August 2003). "Rounding Up Roosevelt Dimes". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 109.

- Weikert, Edward L. Jr. (June 1946). "Numismatic News from the Capitol". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 646.

External links

Media related to Roosevelt dimes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Roosevelt dimes at Wikimedia Commons