A policeman is a hand-held flexible natural-rubber or plastic scraper. The common type of it is attached to a glass rod and used in chemical laboratories to transfer residues of precipitate or solid on glass surfaces when performing gravimetric analysis. This equipment works well under gentle, delicate and precise requirement. A policeman also comes in various sizes, shapes, and types. Some of them come in one-piece flexible plastic version and some in stainless. The origin of the policeman and its name cannot be identified for sure but some clues led back to the 19th century from German chemist Carl Remigius Fresenius.

Structure

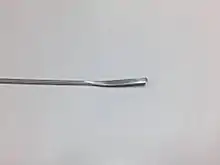

A policeman is generally a flexible natural-rubber blade attached to a glass rod, which is typically 5 mm to 6 mm diameter and 150 mm long. However, it also comes in various sizes and shapes depending on its uses. The rubber material provides chemical resistance. In some designs, there is no glass rod, but instead the whole item is made of plastic or stainless steel and is shaped into a spatula or scraper shape at the end.

Uses

A policeman can be used for cleaning the inside of glassware, or for getting the last bit of precipitate out of a vessel. Especially in chemical laboratories it is often used to transfer residues of precipitate or solid on glass surfaces when performing the gravimetric analysis.

It also used in biological laboratories, to transfer tissue culture cells from a plate to a suspension. It feature is to prevent the glass rod from scratching or breaking glassware.

Origin

There is no answer on where the name "policeman" comes from, though it may be related to the function of the instrument.

- It is like the police in that it protects the beaker from scratching.[1]

- It is like the police in that it gathers up any stray or escaped particles of precipitate on the beaker wall.[1]

In chemistry, gravimetric analysis is essential. After precipitating the chemical element of interest, successfully transferring all of the precipitate to the filtration funnel for separation from the supernatant liquid is required. This can be done by using a stream of distilled water from a wash bottle. This is less effective because dense precipitates may become compacted at the bottom of the beaker, while light precipitates may be dispersed on the walls of the beaker. A glass rod can be used to remove the precipitate but this risks poking a hole in the bottom of the beaker or scratching the beaker wall. In the 19th century, German chemist, Carl Remigius Fresenius suggested a solution to overcome this problem using a device similar to the rubber policeman.[1]

Then rubber policeman was also recorded in 1910 edition of J. C. Olsen's textbook of quantitative analysis that states "particles adhering to the glass must be removed by means of a so-called policeman, which is made by inserting the end of a rather thick large-sized glass stirring-rod into a short piece of rubber tubing. The rubber tube should be left protruding slightly beyond the end of the glass tube and sealed together with a little bicycle [i.e. rubber] cement."[1]

However, it seems that Olsen has nothing to do with the mass production and sales of this invention. Instead, Oesper Collections catalog indicated that Henry Heil Company of St. Louis sold policemen as early as 1904.[1]

The second speculation is the most likely the one since in the 1937 edition of Hackh's Chemical Dictionary "platinum policeman," defined as "a platinum-iridium claw that fits over a glass rod and is used to hold a quantitative filter during ignition,"[2] which the purpose of the policeman was to prevent the escape of stray filter paper from the crucible during the ignition process that causes thermal updrafts from the burner. Therefore, for policeman, it likely means to prevent the escape of stray precipitate.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jensen, William B (2008). "The Origin of the Rubber Policeman" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Education. 85 (776): 776. Bibcode:2008JChEd..85..776J. doi:10.1021/ed085p776. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Hackh, Ingo Waldemar Dagobert; Grant, Julius (1937). Hackh's chemical dictionary: containing the words generally used in chemistry. The University of California: P. Blakiston's son & co., inc. p. 564.