| |||||||||||||||||

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 69.67% (first round) 68.78% (second round) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Second round results by federal subject Yeltsin: 45–50% 50–55% 55–60% 60–65% 65–70% 70–75% 75–80% Zyuganov: 45–50% 50–55% 55–60% 60–65% | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

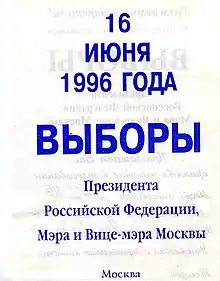

Presidential elections were held in Russia on 16 June 1996, with a second round being held on 3 July. It resulted in a victory for the incumbent President of Russia Boris Yeltsin, who ran as an independent politician. Yeltsin defeated Communist challenger Gennady Zyuganov in the run-off, receiving 54.4% of the vote. Yeltsin's second inauguration ceremony took place on 9 August.

Yeltsin would not complete the second term for which he was elected, as he resigned on 31 December 1999, eight months before the scheduled end of his term on 9 August 2000. This was the first presidential election to take place in post-Soviet Russia. This has also been so far the only Russian presidential election in which no candidate was able to win on the first round, and as such a run-off was necessary.

Background

In 1991, Boris Yeltsin was elected to a five-year term as President of Russia, which was still a part of the Soviet Union at the time. The next election was scheduled be held sometime in 1996.[1] In late December 1991, Soviet Russia became a sovereign nation in wake of the dissolution of the Soviet Union. This meant that the scheduled election would now be the first ever presidential election to be held in a fully sovereign Russia.[2]

In a 1993 Russian government referendum question (III), Russian voters rejected holding an early presidential election, and the presidential election remained scheduled to be held in the year 1996. Later in 1993, the Constitution of Russia was adopted. In the constitution, future presidential terms were stipulated to last for four years, meaning that the 1996 election would elect a president to serve a four-year term. When incumbent president Yeltsin launched his reelection campaign in early 1996, he was widely predicted to lose.[3] Public opinion of Yeltsin was at a historical low point.[3] Due to this, there was talk about Yeltsin potentially postponing or canceling the election; however, he ultimately decided against this.[4]

Shortly before the election campaign, Yeltsin had faced a number of significant political humiliations which harmed his political stature. In the 1995 Russian legislative election, the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) had achieved dominance in the State Duma.[4][3] On 9 January 1996, Chechen rebels seized thousands of hostages in Dagestan and Yeltsin's response to this was viewed as a failure.[3] Additionally, Yeltsin was overseeing a terrible economy. Russian economy was still contracting and many workers had continued to be unpaid for months.[3]

By early 1996, Yeltsin's public approval was so poor that he was polling at fifth place among presidential candidates, with only 8 percent support, while CPRF leader Gennady Zyuganov was in the lead with 21 percent support. When Zyuganov showed up at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in February 1996, many Western leaders and the international media were eager to see him, and treated him with regards to believing that he would likely be the next president of Russia.[3]

Candidates

Registered candidates

Withdrawn candidates

| Candidate name, age, political party |

Political offices | Campaign | Details | Registration date | Date of withdrawal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aman Tuleyev (52) Independent |

.jpg.webp) |

Chairman of the Kemerovo Oblast Council of People's Deputies | (campaign) | He was registered as a candidate on 26 April 1996, but withdrew his candidacy on 8 June 1996 to support Gennady Zyuganov. Since Tuleyev withdrew his candidacy after the deadline, he was included in the ballots and even received 308 votes during the early voting. | 26 April 1996[5][6] | 8 June 1996 | |

Campaigning

Vladimir Bryntsalov

Pharmaceutical businessman Vladimir Bryntsalov ran as the candidate of the Russian Socialist Party.

Brytsalov claimed that his leadership would eliminate the country's poverty, promising that if he were elected, there would be "no poor pensioners, no poor workers, no poor entrepreneurs, no poor farmers."[8]

His plan, which he dubbed "Russian socialism", was for large companies to begin paying wages comparable to companies in other industrialized nations. The plan anticipated that the employees of the companies would consequentially pay larger income taxes, spend more on consumer goods, and increase their productivity at their jobs. The feasibility of this plan was criticized, as Russian companies were considered to be unable to pay such wages.[8]

Brytsalov promoted himself with the superlative claim of being "the richest man in Russia" and flaunted his wealth.[8]

Despite being a (recently elected) deputy of the State Duma, Brytsalov did not have a voting-record. In his legislative career, he had very low attendance and extremely little participation.[9]

Brytsalov was seen as a marginal candidate, and was generally regarded as unlikely to win the election.[8]

Mikhail Gorbachev

Former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev ran as an independent candidate. He ran as a self-proclaimed social democrat. His campaign was hampered both by strong public disdain towards him and a strong lack of media coverage for his candidacy.

Svyatoslav Fyodorov

Politician and renown ophthalmologist Svyatoslav Fyodorov ran as the candidate of the Party of Workers' Self-Government. He is the founder and leader of the party, which was, at the time, arguably the most influential social-democratic movement in Russia.[10]

Fyodorov was considered to be on the center-left of the political spectrum.[11]

In 1994 Fyodorov had described his political objective by stating, "I want peasants to own farms, workers to own factories, physicians to own clinics, and everyone to pay a 30% tax, and the rest is theirs."[10]

Fyodorov advocated for the mass creation of joint stock companies to guarantee workers a share of profits and allow them to actively participate in management of their companies. He dubbed this concept "democratic capitalism" or "popular socialism".[10] He had advocated such a policy since as early as 1991.[12] Fyodorov advocated for economic freedom, simple and moderate taxation, stimulation of production, and a ban on exports of most raw materials.[10] Fyodorov promised that his policies would double the nation's GDP within five years.[13] Fyodorov proclaimed to draw inspiration in his politics from both Ross Perot and Deng Xiaoping.[10]

Up until early May, Fyodorov unsuccessfully attempted to negotiate the creation of a third force coalition, with negotiations largely centering on a coalition between him and fellow candidates Yavlinsky and Lebed.[14]

Alexander Lebed

General Alexander Lebed ran as the nominee of the Congress of Russian Communities, a centrist nationalist party. Lebed promoted himself as an authoritative leader that would introduce law and order, tackle corruption and allow capitalism to blossom.[15][16] While he presented an authoritarian personality, he held moderate positions.[17]

After reaching an informal agreement with Yeltsin in April (under which Lebed promised to endorse Yeltsin in the second round of the election), Lebed began to see positive news coverage, as well as a greater overall quantity of media coverage. This was done as part of an effort by Yeltsin's camp to promote Lebed in the hopes that he would syphon off votes from other nationalist candidates in the first-round.[4]

Up until early May, Lebed had entertained negotiations with Yavlinsky and Fyodorov to jointly form a third force coalition.[4]

Martin Shakkum

Martin Shakkum ran as an independent candidate. An associate of radical economist Stanislav Shatalin, Shakkum was on the right wing of the Russian political spectrum.[16] While he presented an authoritarian personality, he held moderate positions on many social issues.[17]

Aman Tuleyev

Independent candidate Aman Tuleyev (a member of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation) styled himself as a "Muslim Communist".[18] The head of the Kemerovo Oblast legislature, Tuleyev was considered to be charismatic, energetic, and well as well-liked by the Communist Party's base. He turned-in his signatures the day before the deadline. He was considered to be a fallback communist candidate, in case Zyuganov's candidacy faltered.[19]

Tuleyev's rhetoric straddled between hard-line communism and social-democracy. Generally a hard-liner, he had nonetheless occasionally taken moderate stances, such as seeking tax cuts. Tuleyev's positions centered upon communism and creating a disciplined (uncorrupt) government.[19]

Tuleyev dropped out of the race on 8 June and endorsed Zyuganov.[20]

Despite the fact that Tuleyev dropped out of the race before the election, he had already been on the ballot during a portion of the early voting period.

Yury Vlasov

Politician and former Olympic weightlifter Yury Vlasov ran as an independent candidate. His politics were characterized as nationalist.[5][16] Vlasov openly espoused antisemitic rhetoric.[21]

Vlasov dubbed his politics as "people's patriotism".[22] His campaign platform proclaimed, "There is only one single force that is able to unite almost all and at the same time become the ideological basis of the Russian state – popular patriotism".[23]

While he had been a supporter of democratic reforms in the Soviet Union, following its collapse Vlasov had embraced authoritarian political views.[24]

Vlasov likened his politics to Gaullism. He claimed that his politics were a more effective unifying force than communist or democratic ideals.[22]

While he was nominally an independent candidate, Vlasov's campaign was supported by the People's National Party. However, by the end of the election, many in the party grew dissatisfied with Vlasov's campaign style, believing he failed to campaign aggressively enough.[25]

Despite polling at under one percent, Vlasov had stated that he anticipated capturing between six and seven percent of the vote. He swore to refuse supporting either Yeltsin or support Zyuganov in the runoff.[22]

Grigory Yavlinsky

Grigory Yavlinsky ran as the nominee of Yabloko. Yavlinsky officially accepted Yabloko's nomination on 27 January.[13]

In terms of social issues, Yavlinsky occupied the political left.[26] In terms of economic issues, Yavlinsky occupied the far-right of the Russian political spectrum. His ideology most strongly appealed to Russia's population of young intellectuals.[16]

Yabloko has been a programmatic party, as opposed to a populist one. This proved to be a weakness for Yavlinsky's campaign, as he and his party opted to maintain their long-established party positions on many issues, rather than reshaping their agenda in order to better capitalize on the political tides. This had also been the case in the preceding 1995 electoral campaign, during which Yabloko similarly had opted to focus on complex economic issues, rather than focusing on bread and butter issues.[26]

Up until early May Yavlinsky unsuccessfully attempted to negotiate the creation of a third force coalition, with negotiations largely centering on a coalition between him and fellow candidates Lebed and Fyodorov.[4]

Boris Yeltsin

Incumbent Boris Yeltsin ran for reelection as an independent candidate.

While his prospects of winning were originally faltering, Yeltsin was able to resuscitate his image and pull off a successful campaign.[4]

Yeltsin's original strategy, devised by Oleg Soskovets, involved him pivoting towards the nationalist wing of Russia's politics in order to directly compete for votes with Zyuganov and Zhirinovsky.[4] However, this strategy was ultimately abandoned in favor of one devised by reformists, British and American consultants. Yeltsin's new campaign strategy was, essentially, to convince voters that they had to choose him as the lesser of two evils. This strategy sought to recast Yeltsin as an individual single-handedly fighting to stave off communist control. The campaign framed a narrative that portrayed Yeltsin as Russia's best hope for stability.[4] The campaign worked to shift the narrative of the election into a referendum on whether voters wanted to return to their communist past (with Zyuganov), or continue with reforms (with Yeltsin).[4]

Yeltsin was able to leverage the power of his office. This included using government funds to finance campaign promises, utilizing state media organizations, and currying favoritism amongst financial and media oligarchs.[4]

Two days after the conclusion of the first round, Yeltsin appointed former general Alexander Lebed, who had finished third with 14.7% of vote, to the post of Secretary of Security Council of the Russian Federation and the President's National Security Advisor.[27] Lebed in turn endorsed Yeltsin in the runoff election. Meanwhile, Yeltsin suffered from a serious heart attack and disappeared from public view. His condition was kept secret through 3 July second round election. During this period of time, Yeltsin's campaign team created a "virtual Yeltsin" shown in the media through staged interviews that never happened and pre-recorded radio addresses.[3]

Vladimir Zhirinovsky

Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR) leader Vladimir Zhirinovsky campaigned on nationalist rhetoric.

After his surprisingly strong third-place finish in the 1991 presidential election and the surprisingly strong first-place performance of the LDPR in the 1993 legislative election, Zhirinivsky had once been seen as a rising force in Russian politics, and a future contender for the presidency.[4][28][29] However, boorish and outlandish conduct by Zhirinovsky had diminished the public perception of his stature to such a degree that, by 1996, he was seen as a buffoonish figure and was no longer seen as a viable candidate.[4][29]

Gennady Zyuganov

Communist Party of the Russian Federation-leader Gennady Zyuganov successfully advanced to the second-round of the election, where he was defeated by Yeltsin.

Coming off of a very successful Communist Party performance in the 1995 legislative election, when he launched his campaign, Zyuganov had originally been seen as the frontrunner to win the election.[4]

Conduct

.JPG.webp)

Although most contemporaneous reports certified the 1996 election result, the election has been associated with various counts of pro-Yeltsin media bias and foreign influence.

Contemporary analysis

In their 1996 report, the International Republican Institute stated that their election observers, "witnessed no deliberate attempts to commit electoral fraud and, indeed, in the tracking of protocols through the various levels of Russia's electoral system, observed transparency in the process."[30]

In their 1996 analysis, the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs declared that, while the election failed to be "free and fair" in regards to media coverage and campaign financing, it appeared to have largely succeeded in being "free and fair" in regards to the administration of voting and vote-counting.[31]

Observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) reported in 1996 that the first round of the election, "appeared to be generally well run, and not seriously marred by some problems which occurred in the pre-election campaign. The delegation considered the first round of the Russian Presidential elections to have been conducted in a generally free and fair manner."[32]

The OSCE also reported that, "Delegation members considered voter participation in the political campaign to be quite active compared to previous Russian elections. A relatively open flow of information concerning candidates and their platforms was made available to voters during the pre-election campaign. However, opposition candidates charged that the state controlled electronic broadcast media did not provide fair and balanced coverage, and this was also observed to be the case by delegation members. The bias appeared to be primarily in favor of the President."[32] Additionally, the OSCE reported that, "The delegation found that Polling Station Election Committees (PSECs) generally followed proper procedures and enforced the one-man-one-vote principle, although scattered instances of minor irregularities, such as family voting and voting outside of polling booths were observed."[32]

In a 1996 post-election analysis published in the journal Presidential Studies Quarterly, Erik Depov asserted, "The inaccuracy of many early predictions was primarily because Yeltsin's successful re-election bid had as much to do with the dynamics of the electoral campaign as with the results of his first term in office. If the 1996 presidential campaign proved anything, it illustrated the danger of underestimating Yeltsin's ability to meet a serious political challenge head on and prevail despite apparently insurmountable odds."[2]

During the campaign, Yeltsin's opponents criticized his use of state coffers to fund programs that would bolster his approval with voters.[33] Yeltsin had been utilizing state finances to fund programs (such as pensions) with the aim of convincing voters of his willingness to fulfill promises he which he was making on the campaign trail.[33] Yeltsin's opponents charged that, in doing this, he was essentially buying votes. However, Yeltsin's team argued that he was simply doing his job as president.[33]

During the second round campaign, Zyuganov asserted in a letter to the parliament, the Central Electoral Commission, and the media that Yeltsin was buying votes with money that should be used to pay wage and pension arrears and that he had pressured local leaders into working for his campaign. He also alleged that Yeltsin was using "tens of trillions of rubles" from the state budget for campaign purposes. Zyuganov argued that such practices would call into question the results of the voting and urged immediate measures that would insure equal conditions for the candidates.[34]

Pro-Yeltsin media bias

Yeltsin benefited from an immense media bias favoring his campaign.[4][35]

In 1991, at the time of the previous presidential election, Russia had only two major television channels. RTR had supported Yeltsin, while ORT had criticized him and provided broad coverage of the views of his opponents. In the 1996 election, however, none of Russia's major television networks were critical of Yeltsin.[35][31] Yeltsin had successfully enlisted the national television channels (ORT, RTR, NTV) and most of the written press to essentially act as agents of his campaign.[4][35]

The European Institute for Media found that Yeltsin received 53% of all media coverage of the campaign, while Zyuganov received only 18%. In their evaluation of the biases of news stories, EIM awarded each candidate 1 point for every positive story they received and subtracted a point for every negative story they received. In the first round of the election, Yeltsin scored +492 and Zyuganov scored −313. In the second round of the election, Yeltsin scored +247 and Zyuganov scored −240.[35]

Television networks marginalized all of Yeltsin's opponents aside from Zyuganov, helping to create the perception that there were only two viable candidates. This allowed Yeltsin to pose as the lesser-evil. Near the end of the election's first-round, however, the networks began also providing coverage to the candidacy of Lebed,[31] who had already agreed to support Yeltsin in the second round.[4]

Supplementing the work of the numerous public relations and media firms that were hired by the Yeltsin campaign, a number of media outlets "volunteered" their services to Yeltsin's reelection effort. For instance, Kommersant (one of the most prominent business newspapers in the country) published an anti-communist paper called Ne Dai Bog (meaning, "God forbid").[4] At ORT, a special committee was placed in charge of planning a marathon of anticommunist films and documentaries to be broadcast on the channel ahead of the election.[4]

Led by the efforts of Mikhail Lesin, the media painted a picture of a fateful choice for Russia, between Yeltsin and a "return to totalitarianism." They even played up the threat of civil war if a Communist were elected president.[36]

One of the reasons for the media's overwhelming favoritism of Yeltsin was their fear that a Communist government would dismantle Russia's right to a free press.[35][29] Another factor contributing to the media's support of Yeltsin was that his government still owned two of the national television channels, and still provided the majority of funding to the majority of independent newspapers.[35] In addition, Yeltsin's government also was in charge of supplying licenses to media outlets. Yeltsin's government and Luzhkov, mayor of Moscow, flexed their power and reminded the owners, publishers, and editors that newspaper licenses and Moscow leases for facilities were "under review".[35] There were also instances of direct payments made for positive coverage (so-called "dollar journalism").[35]

Yeltsin had managed to enlist Russia's emerging business elite to work in his campaign, including those who ran media corporations. This included Vladimir Gusinsky, owner of Most Bank, Independent Television and NTV. NTV which had, prior to the campaign, been critical towards Yeltsin's actions in Chechnya, changed the tone of their coverage. Igor Malashenko, Gusinsky's appointed head of NTV, even joined the Yeltsin campaign and led its media relations in a rather visible conflict-of-interest.[35] In early 1996, Gusinsky and his political rival Boris Berezovsky (chairman of the Board of ORT) decided that they would put aside their differences in order to work together to support the reelection Boris Yeltsin.[4] By mid-1996, Yeltsin had recruited a team of a handful of financial and media oligarchs to bankroll the Yeltsin campaign and guarantee favorable media coverage the president on national television and in leading newspapers.[37] In return, Yeltsin's presidential administration allowed well-connected Russian business leaders to acquire majority stakes in some of Russia's most valuable state-owned assets.[38]

Additionally, to further guarantee consistent media coverage, in February Yeltsin had fired the chairperson of the All-Russia State Television and Radio Broadcasting Company and replaced him with Eduard Sagalaev.[39][40]

While the anti-communist pro-Yeltsin media bias certainly contributed to Yeltsin's victory, it was not the sole factor. A similar anti-communist media bias in the run-up to the 1995 parliamentary elections had failed to prevent a communist victory.[41] Additionally, Yeltsin himself had been able to win the 1991 presidential election in spite of a strongly unfavorable media bias towards him.[42]

Violations of campaign laws

Yeltsin's campaign disregarded numerous campaign regulations. Analysis has indicated that Yeltsin's campaign spent well in excess of spending limits.[4] Yeltsin also violated a law against broadcasting advertisements before 15 March.[43] Yeltsin undertook many abuses of his power in order to assist his campaign effort.[44]

Following the election a financial fraud investigation was launched against Yeltsin's campaign.

Fraud

Some instances of fraud were indicated to have taken place, but the various political actors, including the opposition, did not challenge the result.[45]

The Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation found in 1996 that the original second-round results reported from Mordovia were falsified. A significant number of votes that had been cast for Zyuganov were recorded as "Against All Candidates". The vote totals from Mordovia were subsequently adjusted by the Central Election Commission in order to remedy this.[46][47]

The Central Election Commission also discovered fraud in Dagestan, an ethnic republic which had experienced a very improbable change in voting patterns between rounds. The vote totals were revised to remedy this.[48][49][50][51]

Another instance of fraud was discovered in Karachay-Cherkessia by the Central Election Commission. The vote totals were adjusted to remedy for this as well.[52]

Allegations of unfairness and fraud

There have been a number of allegations claiming that there were further, and greater, instances of fraud than the aforementioned instances that had been discovered by the Central Election Commission. They include a number of allegations that assert that the election was unfair and favored Yeltsin, as well as some allegations that go as far as to assert that the entire election was fraudulent.[53]

In addition to federal subjects in which fraud was discovered by the CEC, some results, such as those from Russia's ethnic republics of Tatarstan and Bashkortostan, showed highly-unlikely changes in voting patterns between the two rounds of voting. That has aroused suspicions of election fraud.[49][50][51] However, any fraud that may have contributed to those discrepancies is unlikely to have had a material effect on the outcome of the election.[54] One hypothesis that has been given for the dramatic increase in support that Yeltsin saw in some regions was that prior to the second round vote, administrative pressure was applied in those regions to coerce voters into supporting Yeltsin.[44][55]

Allegations have been made by some that in the first round of the election, several regions of Russia committed electoral fraud in favor of Zyuganov.[56] It has also been further alleged by some that several of the republics switched the direction of their fraud during the second round to favor Yeltsin instead.[56]

Mikhail Gorbachev has voiced a belief that the results of the election were falsified. He has stated that he believes that the results underreported his actual share of the vote.[57]

At a meeting with opposition leaders in 2012, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev was reported to have said, "There is hardly any doubt who won [that race]. It was not Boris Nikolaevich Yeltsin."[53]

American influence

After the election, a group of American consultants that worked for the Yeltsin campaign sought to take credit for Yeltsin's successful reelection in a profile published in the July 1996 issue of Time magazine with the headline, "Yanks to the Rescue".[58][59] Their account was later the basis of the 2003 comedy Spinning Boris. However, there was reporting that indicated that their work for Yeltsin's campaign did not play a consequential role in shaping the campaign, with Time receiving accusations of poor journalism and sensationalism for publishing the consultants' claims about their importance to the campaign without practicing skepticism.[60][61] Additionally, it had not at all been unusual for foreign consultants to work on campaigns in the nation's fledgling electoral politics.[62]

Knowing that his voter base was pro-Western, Yeltsin lobbied President Clinton to speak praisefully of Russia's transition to democracy. Yeltsin believed that this would strengthen his support from voters.[63] Yeltsin warned President Clinton of the possible ramifications of a Zyuganov victory, saying, "There is a U.S. press campaign suggesting that people should not be afraid of the communists; that they are good, honorable and kind people. I warn people not to believe this. More than half of them are fanatics; they would destroy everything. It would mean civil war. They would abolish the boundaries between the republics. They want to take back Crimea; they even make claims against Alaska. ... There are two paths for Russia's development. I do not need power. But when I felt the threat of communism, I decided that I had to run. We will prevent it."[64] In their conversations, President Clinton assured Yeltsin that he would give him his publicly declared personal endorsement, saying, "I've been trying to find a way to say to the Russian people 'this election will have consequences,' and we are clear about what it is we support."[64][65] Yeltsin made other requests, such as admission into the G8 (not granted), a $2.5 billion direct cash loan to the government (not granted), and a delay in NATO expansion (granted). Clinton refrained from undertaking covert operations to support Yeltsin, however, to prevent spurring backlash if such efforts were to be discovered.[66]

In January 1997, noting the support Yeltsin had received in 1996 from the Clinton administration, former candidate Alexander Lebed visited the United States to rally support from American businesses for a potential run in the 2000 Russian presidential election. As one analyst wrote at the time (of Lebed): "He may perceive that Yeltsin benefited greatly from support from the Americans in the last campaign. Bill Clinton made a trip to Moscow during the campaign. And the International Monetary Fund extended loans that enabled the Government to make credible promises to pay wages."[67][68]

Some have argued that the role of American president Bill Clinton's administration in securing an International Monetary Fund loan for Russia had an impact on the election, with some critics characterizing it as an act of foreign electoral intervention.[69][70]

Opinion polls

Results

| Candidate | Party | First round | Second round | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||

| Boris Yeltsin | Independent | 26,665,495 | 35.79 | 40,203,948 | 54.40 | |

| Gennady Zyuganov | Communist Party | 24,211,686 | 32.49 | 30,102,288 | 40.73 | |

| Alexander Lebed | Congress of Russian Communities | 10,974,736 | 14.73 | |||

| Grigory Yavlinsky | Yabloko | 5,550,752 | 7.45 | |||

| Vladimir Zhirinovsky | Liberal Democratic Party | 4,311,479 | 5.79 | |||

| Svyatoslav Fyodorov | Party of Workers' Self-Government | 699,158 | 0.94 | |||

| Mikhail Gorbachev | Independent | 386,069 | 0.52 | |||

| Martin Shakkum | Socialist People's Party | 277,068 | 0.37 | |||

| Yury Vlasov | Independent | 151,282 | 0.20 | |||

| Vladimir Bryntsalov | Russian Socialist Party | 123,065 | 0.17 | |||

| Aman Tuleyev[lower-alpha 1] | Independent | 308 | 0.00 | |||

| Against all | 1,163,921 | 1.56 | 3,604,462 | 4.88 | ||

| Total | 74,515,019 | 100.00 | 73,910,698 | 100.00 | ||

| Valid votes | 74,515,019 | 98.58 | 73,910,698 | 98.95 | ||

| Invalid/blank votes | 1,072,120 | 1.42 | 780,592 | 1.05 | ||

| Total votes | 75,587,139 | 100.00 | 74,691,290 | 100.00 | ||

| Registered voters/turnout | 108,495,023 | 69.67 | 108,589,050 | 68.78 | ||

| Source: Nohlen & Stöver,[71] Colton,[72] CEC | ||||||

- ↑ Withdrew his candidacy before the election but received 308 votes during the early voting (up to the withdrawal of the candidature), which were credited as valid.

First round results by federal subject

| Federal subjects with a plurality of vote for Yeltsin |

| Federal subjects with a plurality of vote for Zyuganov |

| Boris Yeltsin Independent |

Gennady Zyuganov CPRF |

Alexander Lebed KRO |

Grigory Yavlinsky Yabloko |

Vladimir Zhirinovsky LDPR |

Vladimir Bryntsalov RSP |

Svyatoslav Fyodorov PST |

Mikhail Gorbachev Independent |

Martin Shakkum Independent |

Yury Vlasov Independent |

Aman Tuleyev Independent |

Against all | Total | Invalid ballots | Registered voters/turnout | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal subject | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | No. | No. | % |

| Adygea | 45,374 | 20.0% | 116,701 | 51.5% | 31,710 | 14.0% | 11,977 | 5.3% | 11,494 | 5.1% | 319 | 0.1% | 2,245 | 1.0% | 557 | 0.3% | 720 | 0.3% | 342 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 2,380 | 1.1% | 223,819 | 2,799 | 338,369 | |

| Agin-Buryat Autonomous Okrug | 13,647 | 44.7% | 10,903 | 35.7% | 1,630 | 5.3% | 794 | 2.6% | 1,732 | 5.7% | 72 | 0.2% | 231 | 0.7% | 340 | 1.1% | 77 | 0.3% | 42 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 384 | 1.3% | 29,852 | 656 | 44,176 | |

| Altai Krai | 300,499 | 21.8% | 578,478 | 42.0% | 267,212 | 19.4% | 69,619 | 5.1% | 101,669 | 7.4% | 1,642 | 0.1% | 9,439 | 0.7% | 6,387 | 0.5% | 4,688 | 0.3% | 1,861 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 18,521 | 1.3% | 1,360,019 | 18,140 | 1,950,248 | |

| Altai Republic | 27,562 | 28.5% | 42,204 | 43.6% | 12,614 | 13.0% | 3,347 | 3.5% | 4,671 | 4.8% | 173 | 0.2% | 836 | 0.9% | 967 | 1.0% | 473 | 0.5% | 228 | 0.2% | 2 | 0.0% | 1,552 | 1.6% | 94,629 | 2,158 | 130,610 | |

| Amur Oblast | 127,223 | 26.6% | 200,186 | 41.9% | 56,610 | 11.8% | 28,985 | 6.1% | 37,852 | 7.9% | 756 | 0.2% | 5,651 | 1.2% | 2,374 | 0.5% | 1,484 | 0.3% | 867 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 10,222 | 2.1% | 472,210 | 6,105 | 697,451 | |

| Arkhangelsk Oblast | 288,225 | 40.9% | 129,200 | 18.3% | 121,910 | 17.3% | 76,136 | 10.8% | 46,277 | 6.6% | 1,440 | 0.2% | 11,037 | 1.6% | 3,981 | 0.6% | 3,805 | 0.5% | 1,590 | 0.2% | 34 | 0.0% | 13,874 | 2.0% | 697,608 | 8,045 | 1,056,542 | |

| Astrakhan Oblast | 150,190 | 29.5% | 185,925 | 36.5% | 82,140 | 16.1% | 30,710 | 6.0% | 36,407 | 7.2% | 704 | 0.1% | 4,674 | 0.9% | 1,623 | 0.3% | 916 | 0.2% | 762 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 7,018 | 1.4% | 501,069 | 7,699 | 734,487 | |

| Bashkortostan | 769,089 | 34.2% | 941,539 | 41.9% | 200,859 | 8.9% | 152,557 | 6.8% | 64,541 | 2.9% | 3,949 | 0.2% | 12,256 | 0.5% | 17,411 | 0.8% | 7,202 | 0.3% | 2,992 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 31,861 | 1.4% | 2,204,156 | 45,139 | 2,846,065 | |

| Belgorod Oblast | 189,320 | 22.9% | 383,688 | 46.4% | 140,322 | 17.0% | 47,592 | 5.8% | 35,666 | 4.3% | 1,018 | 0.1% | 4,336 | 5.8% | 2,777 | 0.3% | 1,220 | 0.2% | 1,106 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 10,373 | 1.3% | 817,418 | 10,397 | 1,093,357 | |

| Bryansk Oblast | 210,257 | 26.2% | 397,454 | 49.6% | 92,948 | 11.6% | 27,904 | 3.5% | 40,777 | 5.1% | 856 | 0.1% | 4,746 | 0.6% | 2,657 | 0.3% | 1,190 | 0.2% | 1,035 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 10,247 | 1.3% | 790,071 | 11,528 | 1,110,307 | |

| Buryatia | 134,856 | 30.6% | 177,293 | 40.2% | 46,609 | 10.6% | 33,451 | 7.6% | 21,329 | 4.8% | 554 | 0.1% | 5,464 | 1.2% | 2,544 | 0.6% | 1,190 | 0.3% | 770 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 6,185 | 0.4% | 430,245 | 10,541 | 688,483 | |

| Chechnya | 239,905 | 65.1% | 60,119 | 16.3% | 9,371 | 2.5% | 15,666 | 4.3% | 5,172 | 1.4% | 817 | 0.2% | 3,804 | 1.0% | 6,508 | 1.8% | 1,118 | 0.3% | 1,489 | 0.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 8,190 | 2.2% | 352,159 | 16,318 | 507,243 | |

| Chelyabinsk Oblast | 685,273 | 36.6% | 463,071 | 24.7% | 371,120 | 19.8% | 164,230 | 8.8% | 97,937 | 5.2% | 2,703 | 0.2% | 13,732 | 0.7% | 8,936 | 0.5% | 6,594 | 0.4% | 2,716 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 25,542 | 1.4% | 1,841,854 | 30,487 | 2,663,820 | |

| Chita Oblast | 130,011 | 24.5% | 207,282 | 39.1% | 61,981 | 11.7% | 29,071 | 5.5% | 68,603 | 13.0% | 840 | 0.2% | 6,688 | 1.3% | 2,870 | 0.5% | 1,794 | 0.3% | 949 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 11,116 | 2.1% | 521,205 | 8,645 | 823,229 | |

| Chukotka Autonomous Okrug | 20,859 | 48.5% | 5,808 | 13.5% | 7,337 | 17.1% | 2,741 | 6.4% | 3,254 | 7.6% | 114 | 0.3% | 844 | 2.0% | 264 | 0.6% | 116 | 0.3% | 124 | 0.3% | 17 | 0.0% | 1,123 | 2.6% | 42,601 | 418 | 58,848 | |

| Chuvashia | 132,422 | 20.6% | 347,524 | 53.9% | 49,296 | 7.7% | 29,446 | 3.2% | 27,381 | 4.3% | 977 | 0.2% | 20,906 | 3.2% | 2,329 | 4.3% | 2,166 | 0.3% | 916 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 7,068 | 1.1% | 620431 | 23,945 | 959,432 | |

| Dagestan | 230,614 | 28.5% | 511,202 | 63.2% | 10,799 | 1.3% | 13,753 | 1.7% | 9,041 | 1.1% | 1,026 | 0.1% | 2,208 | 0.3% | 2,791 | 0.4% | 703 | 0.1% | 622 | 0.1% | 15 | 0.0% | 4,336 | 0.5% | 787,110 | 21,418 | 1,172,872 | |

| Evenk Autonomous Okrug | 3,678 | 43.4% | 1,694 | 20.0% | 1,390 | 16.4% | 553 | 6.3% | 597 | 7.1% | 16 | 0.2% | 140 | 1.7% | 69 | 0.8% | 41 | 0.5% | 30 | 0.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 157 | 1.9% | 8,345 | 125 | 12,932 | |

| Ingushetia | 37,129 | 46.3% | 19,653 | 24.5% | 1,786 | 2.2% | 12,195 | 15.2% | 1,398 | 1.7% | 305 | 0.4% | 616 | 0.8% | 3,574 | 4.5% | 299 | 0.4% | 148 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,534 | 1.9% | 78,647 | 1,614 | 114,605 | |

| Irkutsk Oblast | 363,648 | 32.2% | 311,353 | 27.6% | 183,962 | 16.3% | 100,075 | 8.9% | 95,810 | 8.5% | 1,698 | 0.2% | 22,271 | 2.0% | 7,150 | 0.6% | 4,552 | 0.4% | 2,635 | 0.2% | 11 | 0.0% | 19,003 | 1.7% | 1,112,168 | 17,019 | 1,798,752 | |

| Ivanovo Oblast | 204,084 | 29.6% | 160,105 | 23.2% | 203,997 | 29.6% | 41,38 | 6.1% | 48,275 | 7.0% | 1,128 | 0.2% | 4,215 | 0.6% | 2,549 | 0.4% | 1,864 | 0.3% | 1,082 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 11,199 | 1.6% | 642,094 | 8,954 | 957,607 | |

| Jewish Autonomous Oblast | 28,859 | 30.4% | 31,220 | 32.8% | 14,544 | 15.3% | 6,134 | 6.5% | 7,594 | 8.0% | 201 | 0.2% | 1,725 | 1.8% | 626 | 0.7% | 348 | 0.4% | 190 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 2,318 | 2.4% | 93,759 | 1,294 | 140,631 | |

| Kabardino-Balkaria | 163,872 | 43.8% | 139,521 | 37.3% | 36,685 | 9.8% | 12,590 | 3.4% | 5,358 | 1.4% | 465 | 0.1% | 1,809 | 0.5% | 1,290 | 0.3% | 712 | 0.2% | 452 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 2,824 | 0.8% | 365,578 | 8,947 | 507,194 | |

| Kaliningrad Oblast | 173,769 | 33.5% | 119,830 | 23.1% | 110,264 | 19.3% | 66,703 | 12.9% | 37,412 | 7.2% | 878 | 0.2% | 3,189 | 0.6% | 2,245 | 0.4% | 821 | 0.2% | 823 | 0.2% | 9 | 0.0% | 7,506 | 1.5% | 513,449 | 5,818 | 724,142 | |

| Kalmykia | 88,615 | 58.5% | 38,954 | 25.7% | 8,215 | 5.4% | 3,791 | 2.5% | 5,407 | 3.6% | 177 | 0.1% | 633 | 0.4% | 531 | 0.4% | 227 | 0.2% | 121 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,372 | 0.9% | 148,053 | 3,443 | 200,224 | |

| Kaluga Oblast | 190,706 | 31.4% | 241,933 | 35.4% | 94,650 | 15.6% | 45,258 | 7.5% | 31,018 | 5.1% | 1,140 | 0.2% | 5,249 | 0.9% | 2,379 | 0.4% | 2,791 | 0.5% | 1,158 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 9,194 | 1.5% | 598,476 | 8,352 | 832,954 | |

| Kamchatka Oblast | 57,435 | 34.3% | 31,307 | 18.8% | 23,549 | 14.1% | 28,935 | 17.3% | 16,689 | 10.0% | 347 | 0.2% | 1,731 | 1.0% | 872 | 0.5% | 542 | 0.3% | 487 | 0.3% | 20 | 0.0% | 3,840 | 2.3% | 165,754 | 1,740 | 282,857 | |

| Karachay-Cherkessia | 54,823 | 25.8% | 117,677 | 55.4% | 18,624 | 8.8% | 6,527 | 3.1% | 5,286 | 2.5% | 616 | 0.3% | 1,014 | 0.5% | 1,060 | 0.5% | 525 | 0.3% | 229 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,619 | 0.8% | 208,000 | 4,322 | 293,024 | |

| Karelia | 165,584 | 42.4% | 66,428 | 17.0% | 47,0543 | 12.0% | 55,768 | 14.3% | 33,134 | 8.5% | 744 | 0.2% | 3,817 | 1.0% | 1,914 | 0.5% | 2,066 | 0.5% | 722 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 7,573 | 1.9% | 384,803 | 6,137 | 577,087 | |

| Kemerovo Oblast | 332,376 | 23.0% | 561,397 | 38.9% | 220,789 | 15.3% | 77,099 | 5.3% | 167,925 | 11.6% | 1,565 | 0.1% | 23,566 | 1.6% | 7,154 | 0.5% | 5,260 | 0.4% | 1,967 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 23,640 | 0.6% | 1,422,738 | 21,111 | 2,167,343 | |

| Khabarovsk Krai | 288,585 | 39.0% | 169,586 | 22.9% | 90,550 | 12.2% | 77,077 | 10.4% | 64,007 | 8.7% | 988 | 0.1% | 15991 | 2.2% | 5,097 | 0.7% | 2,680 | 0.4% | 1,391 | 0.2% | 5 | 0.0% | 16,239 | 2.2% | 732,196 | 7,580 | 1,103,898 | |

| Khakassia | 75,801 | 29.2% | 91,956 | 35.5% | 32,491 | 12.5% | 18,784 | 7.3% | 25,108 | 9.7% | 458 | 0.2% | 3,098 | 1.2% | 1,643 | 0.6% | 1,074 | 0.4% | 677 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 4,255 | 1.6% | 255,345 | 3,866 | 393,711 | |

| Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug | 271,345 | 52.5% | 66,241 | 12.8% | 78,175 | 15.1% | 34,138 | 6.6% | 39,217 | 7.6% | 799 | 0.2% | 7,178 | 1.4% | 2,984 | 0.6% | 2,424 | 0.5% | 822 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 7,040 | 1.4% | 510,363 | 6,143 | 827,553 | |

| Kirov Oblast | 272,471 | 31.2% | 252,624 | 29.0% | 119,504 | 13.7% | 105,934 | 12.2% | 75,155 | 8.6% | 1,688 | 0.2% | 7,232 | 0.8% | 3,706 | 0.4% | 3,499 | 0.4% | 1,609 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 17,554 | 2.0% | 860,976 | 11,194 | 1,199,668 | |

| Komi Republic | 202,373 | 40.5% | 81,572 | 16.3% | 90,830 | 18.2% | 47,240 | 9.5% | 49,103 | 9.8% | 878 | 0.18% | 4,262 | 0.9% | 2,992 | 0.6% | 1,990 | 0.4% | 949 | 0.2% | 3 | 0.0% | 9,193 | 1.8% | 491,385 | 8,572 | 799,889 | |

| Komi-Permyak Autonomous Okrug | 37,649 | 53.3% | 16,751 | 23.7% | 3,850 | 5.5% | 2,116 | 3.0% | 6,013 | 8.5% | 174 | 0.3% | 360 | 0.5% | 603 | 0.9% | 208 | 0.3% | 116 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,460 | 2.01% | 69,300 | 1,350 | 102,136 | |

| Koryak Autonomous Okrug | 7,270 | 46.0% | 2,367 | 15.0% | 2,497 | 15.8% | 1,411 | 8.9% | 1,028 | 6.5% | 55 | 0.4% | 208 | 1.3% | 136 | 0.9% | 66 | 0.4% | 45 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 459 | 2.9% | 15,542 | 267 | 21,783 | |

| Kostroma Oblast | 122,971 | 28.0% | 125,399 | 28.6% | 102,078 | 23.3% | 34,112 | 7.8% | 33,426 | 7.6% | 747 | 0.2% | 3,357 | 0.8% | 2,024 | 0.5% | 1,197 | 0.3% | 875 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 6,940 | 1.6% | 433,126 | 5,730 | 596,580 | |

| Krasnodar Krai | 682,602 | 26.3% | 1,024,603 | 39.4% | 454,555 | 17.5% | 165,231 | 6.4% | 165,721 | 6.4% | 4,284 | 0.2% | 23,266 | 0.9% | 8,092 | 0.3% | 5,498 | 0.2% | 4,002 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 31,460 | 1.2% | 2,569,314 | 29,791 | 3,878,024 | |

| Krasnoyarsk Krai | 523,135 | 34.8% | 428,781 | 28.5% | 208,494 | 13.9% | 150,527 | 10.0% | 113,853 | 7.6% | 1,947 | 0.1% | 13,264 | 0.9% | 8,885 | 0.6% | 6,127 | 0.4% | 2,471 | 0.2% | 20 | 0.0% | 26,434 | 1.8% | 1,484,038 | 19,410 | 2,141,669 | |

| Kurgan Oblast | 170,311 | 29.3% | 218,464 | 37.5% | 64,877 | 11.1% | 38,479 | 6.6% | 58,143 | 10.0% | 1,071 | 0.2% | 4,582 | 0.8% | 3,112 | 0.5% | 2,029 | 0.4% | 958 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 12,139 | 2.1% | 574,165 | 7,996 | 786,510 | |

| Kursk Oblast | 177,328 | 24.1% | 376,880 | 51.1% | 81,555 | 11.1% | 39,641 | 5.4% | 28,666 | 3.9% | 971 | 0.1% | 4,280 | 0.6% | 2,661 | 0.4% | 1,145 | 0.2% | 1,140 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 9,626 | 1.3% | 723,893 | 13,244 | 1,007,467 | |

| Leningrad Oblast | 348,505 | 37.5% | 215,511 | 23.2% | 168,540 | 18.1% | 107,896 | 11.6% | 39,882 | 4.3% | 2,210 | 0.2% | 11,038 | 1.2% | 5,757 | 0.6% | 3,491 | 0.4% | 1,812 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 15,735 | 1.7% | 920,377 | 9,858 | 1,329,030 | |

| Lipetsk Oblast | 168,077 | 25.1% | 310,671 | 46.4% | 88,165 | 13.2% | 37,251 | 5.6% | 35,638 | 5.3% | 750 | 0.1% | 4,616 | 0.7% | 1,898 | 0.3% | 1,279 | 0.2% | 1,070 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 10,084 | 1.5% | 659,499 | 10,535 | 945,709 | |

| Magadan Oblast | 40,679 | 36.9% | 17,666 | 16.0% | 26,288 | 23.9% | 6,770 | 6.2% | 12,021 | 10.9% | 259 | 0.2% | 1,570 | 1.4% | 517 | 0.5% | 421 | 0.4% | 296 | 0.3% | 5 | 0.0% | 2,677 | 2.4% | 109,169 | 987 | 170,058 | |

| Mari El Republic | 93,124 | 24.4% | 166,131 | 43.4% | 41,948 | 11.0% | 28,179 | 7.4% | 28,418 | 7.4% | 650 | 0.2% | 5,047 | 1.3% | 1,790 | 0.5% | 2,327 | 0.6% | 696 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 7,395 | 1.9% | 375,705 | 6,756 | 550,104 | |

| Mordovia | 116,693 | 24.1% | 240,263 | 49.7% | 51,434 | 10.6% | 14,493 | 3.0% | 33,138 | 6.9% | 627 | 0.1% | 3,323 | 0.7% | 1,439 | 0.3% | 652 | 0.1% | 961 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 4,396 | 0.9% | 467,419 | 15,927 | 688,846 | |

| Moscow | 2,861,058 | 61.2% | 694,862 | 14.9% | 449,900 | 9.6% | 372,524 | 8.0% | 68,285 | 1.5% | 8,891 | 0.2% | 37,790 | 0.8% | 23,524 | 0.5% | 29,858 | 0.6% | 20,614 | 0.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 67,873 | 1.5% | 4,635,180 | 42,771 | 6,784,920 | |

| Moscow Oblast | 1,675,374 | 44.2% | 912,684 | 24.1% | 571,886 | 15.1% | 298,656 | 7.9% | 113,883 | 3.0% | 9,575 | 0.3% | 34,510 | 0.9% | 17,478 | 0.5% | 31,929 | 0.8% | 11,721 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 65,959 | 1.7% | 3,743,655 | 50,920 | 5,375,052 | |

| Murmansk Oblast | 190,719 | 40.6% | 56,789 | 12.1% | 119,396 | 25.4% | 45,435 | 9.7% | 32,775 | 7.0% | 1,154 | 0.3% | 4,177 | 0.9% | 2,447 | 0.5% | 1,166 | 0.3% | 1,743 | 0.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 9,345 | 2.0% | 465,188 | 4,355 | 787,978 | |

| Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 9,033 | 42.6% | 3,891 | 18.4% | 2,537 | 12.0% | 1,619 | 7.6% | 2,104 | 9.9% | 64 | 0.3% | 465 | 2.2% | 215 | 1.0% | 105 | 0.5% | 68 | 0.3% | 12 | 0.0% | 738 | 3.5% | 20,851 | 332 | 29,097 | |

| Nizhny Novgorod Oblast | 657,961 | 34.8% | 614,467 | 32.5% | 279,053 | 14.8% | 134,905 | 7.1% | 102,621 | 5.4% | 4,426 | 0.2% | 16,620 | 0.9% | 8,070 | 0.4% | 5,074 | 0.3% | 4,220 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 32,601 | 1.7% | 1,860,018 | 29,046 | 2,852,173 | |

| North Ossetia-Alania | 57,849 | 19.3% | 187,007 | 62.3% | 28,895 | 9.6% | 5,390 | 1.8% | 9,703 | 3.2% | 460 | 0.2% | 1,705 | 0.6% | 861 | 0.3% | 503 | 0.2% | 556 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 3,303 | 1.1% | 296,132 | 3,899 | 435,145 | |

| Novgorod Oblast | 148,515 | 35.7% | 98,682 | 23.7% | 76,912 | 18.5% | 45,786 | 11.0% | 25,813 | 6.2% | 960 | 0.2% | 3,398 | 0.8% | 2,437 | 0.6% | 1,250 | 0.3% | 773 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 7,045 | 1.7% | 411,531 | 4,734 | 577,881 | |

| Novosibirsk Oblast | 371,210 | 25.6% | 506,791 | 35.0% | 144,918 | 10.0% | 202,117 | 13.9% | 141,440 | 9.8% | 1,505 | 0.1% | 14,609 | 1.0% | 16,106 | 1.1% | 3,086 | 0.2% | 1,864 | 0.1% | 2 | 0.0% | 24,735 | 1.7% | 1,428,383 | 21,131 | 2,036,398 | |

| Omsk Oblast | 369,782 | 32.8% | 417,029 | 37.0% | 94,396 | 8.4% | 101,027 | 9.0% | 78,352 | 7.0% | 1,364 | 0.1% | 8,693 | 0.8% | 5,061 | 0.5% | 7,961 | 0.7% | 1,907 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 23,244 | 2.1% | 1,108,816 | 18,689 | 1,528,138 | |

| Orenburg Oblast | 288,865 | 26.0% | 468,689 | 42.1% | 151,489 | 13.6% | 65,027 | 5.8% | 83,523 | 8.5% | 1,836 | 0.2% | 10,316 | 0.9% | 7,036 | 0.6% | 2,378 | 0.2% | 1,620 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 13,920 | 1.3% | 1,094,699 | 17,835 | 1,582,780 | |

| Oryol Oblast | 109,020 | 21.5% | 275,643 | 54.3% | 59,782 | 11.8% | 19,788 | 3.9% | 22,402 | 4.4% | 589 | 0.1% | 3,187 | 0.6% | 1,580 | 0.3% | 783 | 0.2% | 788 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 8,002 | 1.6% | 501,754 | 6,377 | 687,020 | |

| Penza Oblast | 181,839 | 20.8% | 442,066 | 50.6% | 105,389 | 12.1% | 60,565 | 6.9% | 46,188 | 5.3% | 1,055 | 0.1% | 5,775 | 0.7% | 2,447 | 0.3% | 1,724 | 0.2% | 1,289 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 12,508 | 1.4% | 860,845 | 12,836 | 1,166,105 | |

| Perm Krai | 742,968 | 55.3% | 216,713 | 16.1% | 130,203 | 6.7% | 96,926 | 7.2% | 83,952 | 6.2% | 2,346 | 0.2% | 12,410 | 0.9% | 8,303 | 0.6% | 4,295 | 0.3% | 2,367 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 23,795 | 1.8% | 1,324,278 | 20,067 | 2,020,049 | |

| Primorsky Krai | 308,747 | 29.6% | 256,574 | 24.6% | 203,384 | 19.5% | 74,840 | 7.2% | 133,029 | 12.7% | 1,889 | 0.2% | 13,094 | 1.3% | 5,751 | 0.6% | 8,692 | 0.8% | 2,084 | 0.2% | 42 | 0.0% | 23,619 | 2.3% | 1,031,745 | 13,097 | 1,580,011 | |

| Pskov Oblast | 121,667 | 24.8% | 149,056 | 30.4% | 115,549 | 23.6% | 34,537 | 7.0% | 49,999 | 10.2% | 832 | 0.2% | 3,319 | 0.7% | 2,028 | 0.4% | 1,196 | 0.2% | 738 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 7,023 | 1.4% | 485,935 | 4,497 | 648,971 | |

| Rostov Oblast | 725,949 | 29.1% | 873,609 | 35.0% | 500,263 | 20.0% | 192,273 | 7.7% | 115,162 | 4.6% | 3,114 | 0.1% | 15,082 | 0.6% | 7,925 | 0.3% | 5,312 | 0.2% | 3,591 | 0.1% | 2 | 0.0% | 26,318 | 1.1% | 2,468,600 | 27,853 | 3,301,262 | |

| Ryazan Oblast | 186,477 | 24.7% | 302,484 | 40.1% | 149,544 | 19.8% | 42,242 | 5.6% | 40,968 | 5.4% | 1,089 | 0.1% | 4,981 | 0.7% | 2,641 | 0.4% | 2,347 | 0.3% | 1,372 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 12,206 | 1.6% | 746,351 | 8,525 | 1,027,429 | |

| Sakha Republic | 228,398 | 51.9% | 90,529 | 20.6% | 55,551 | 12.6% | 20,620 | 4.7% | 16,099 | 3.7% | 715 | 0.2% | 1158 | 0.3% | 3,459 | 0.8% | 1,158 | 0.3% | 770 | 0.2% | 12 | 0.0% | 7,342 | 1.7% | 429,300 | 11,178 | 611,990 | |

| Sakhalin Oblast | 87,577 | 29.9% | 78,935 | 26.9% | 54,755 | 18.7% | 27,174 | 9.3% | 26,581 | 9.1% | 569 | 0.2% | 4,030 | 1.4% | 1,683 | 0.6% | 1,207 | 0.4% | 566 | 0.2% | 32 | 0.0% | 6,181 | 2.1% | 289,290 | 4,018 | 462,223 | |

| Saint Petersburg | 1,137,382 | 49.6% | 342,466 | 14.9% | 321,244 | 14.0% | 347,488 | 15.2% | 49,273 | 2.2% | 4,114 | 0.2% | 25,410 | 1.1% | 17,640 | 0.8% | 6,748 | 0.3% | 6,320 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 25,467 | 1.1% | 2,283,552 | 9,415 | 3,695,014 | |

| Samara Oblast | 620,526 | 36.1% | 604,110 | 35.2% | 200,054 | 11.7% | 105,776 | 6.2% | 96,378 | 5.6% | 1,807 | 0.1% | 16,932 | 1.0% | 8,198 | 0.5% | 11,351 | 0.7% | 4,471 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 27,684 | 1.6% | 1,697,287 | 20,298 | 2,459,138 | |

| Saratov Oblast | 426,533 | 28.4% | 624,996 | 41.6% | 191,822 | 12.8% | 79,404 | 5.3% | 106,482 | 7.1% | 2,201 | 0.2% | 14,135 | 0.9% | 5,445 | 0.4% | 4,131 | 0.3% | 2,854 | 0.2% | 2 | 0.0% | 25,043 | 1.7% | 1,483,048 | 19,830 | 2,045,823 | |

| Smolensk Oblast | 141,854 | 22.0% | 287,621 | 44.6% | 102,726 | 15.9% | 32,942 | 5.1% | 53,764 | 8.3% | 783 | 0.1% | 3,834 | 0.6% | 2,347 | 0.4% | 1,603 | 0.3% | 918 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 9194 | 1.4% | 637,586 | 7,675 | 885,377 | |

| Stavropol Krai | 302,236 | 22.0% | 603,570 | 43.9% | 265,729 | 19.3% | 56,353 | 4.1% | 84,991 | 6.2% | 2,133 | 0.2% | 10,654 | 0.8% | 8,219 | 0.6% | 5,397 | 0.4% | 2,091 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 16,479 | 1.2% | 1,357,852 | 15,933 | 1,862,784 | |

| Sverdlovsk Oblast | 1,302,951 | 59.5% | 255,514 | 11.7% | 310,841 | 14.2% | 117,496 | 5.4% | 107,039 | 4.9% | 2,980 | 0.1% | 23,103 | 1.1% | 9,368 | 0.5% | 5,850 | 0.3% | 3,671 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 30,353 | 1.4% | 2,169,166 | 22,506 | 3,440,385 | |

| Tambov Oblast | 144,669 | 20.9% | 361,552 | 52.3% | 81,045 | 11.7% | 32,003 | 4.6% | 42,183 | 6.1% | 991 | 0.1% | 5,576 | 0.8% | 2,103 | 0.3% | 1,343 | 0.2% | 1,174 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 9,413 | 1.4% | 682,052 | 9,829 | 976,750 | |

| Tatarstan | 745,181 | 38.4% | 740,451 | 38.1% | 143,429 | 7.4% | 134,161 | 6.9% | 50,119 | 2.6% | 3,553 | 0.2% | 17,895 | 0.9% | 15,775 | 0.8% | 4,620 | 0.2% | 3,289 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 31,374 | 1.6% | 1,889,847 | 53,720 | 2,635,844 | |

| Taymyr Autonomous Okrug | 9,434 | 49.7% | 2,304 | 12.1% | 2,843 | 15.0% | 1,234 | 6.5% | 1,920 | 10.1% | 33 | 0.2% | 292 | 1.5% | 192 | 1.0% | 100 | 0.5% | 35 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 386 | 2.0% | 18,773 | 207 | 28,940 | |

| Tomsk Oblast | 178,881 | 36.0% | 113,281 | 22.1% | 100,788 | 19.7% | 55,780 | 10.9% | 36,419 | 7.1% | 725 | 0.1% | 4,026 | 0.8% | 3,096 | 0.6% | 1,525 | 0.3% | 881 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 8,224 | 1.6% | 503,626 | 8,252 | 745,336 | |

| Tula Oblast | 311,280 | 30.0% | 314,098 | 30.2% | 249,663 | 24.0% | 68,439 | 6.6% | 47,545 | 4.6% | 1,462 | 0.1% | 6,196 | 0.6% | 3,334 | 0.3% | 3,543 | 0.3% | 1,762 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 15,702 | 1.5% | 1,023,024 | 16,031 | 1,440,267 | |

| Tuva | 69,971 | 59.9% | 24,716 | 21.2% | 5,297 | 4.5% | 4,926 | 4.2% | 3,529 | 3.0% | 175 | 0.2% | 532 | 0.5% | 1,167 | 1.0% | 246 | 0.2% | 169 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 1,170 | 1.0% | 111,898 | 4,851 | 170,685 | |

| Tver Oblast | 299,435 | 32.1% | 313,168 | 33.6% | 159,813 | 17.1% | 64,843 | 7.0% | 51,496 | 5.5% | 1,587 | 0.2% | 6,799 | 0.7% | 3,551 | 0.4% | 3,820 | 0.4% | 1,804 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 16,367 | 1.8% | 922,683 | 9,750 | 1,256,109 | |

| Tyumen Oblast | 238,171 | 39.1% | 116,491 | 27.3% | 80,961 | 13.3% | 34,850 | 5.7% | 57,206 | 9.4% | 982 | 0.2% | 4,988 | 0.8% | 3,224 | 0.5% | 2,150 | 0.4% | 982 | 0.2% | 18 | 0.0% | 10,770 | 1.77% | 600,693 | 8,920 | 907,788 | |

| Udmurtia | 271,865 | 36.8% | 225,074 | 30.5% | 85,125 | 11.5% | 68,215 | 9.2% | 44,243 | 6.0% | 1,404 | 0.2% | 6,802 | 0.9% | 5,092 | 0.7% | 3,056 | 0.4% | 1,679 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 14,731 | 2.0% | 727,286 | 11,375 | 1,151,991 | |

| Ulyanovsk Oblast | 184,218 | 23.8% | 355,066 | 45.8% | 95,559 | 12.3% | 45,748 | 5.9% | 57,67 | 7.4% | 989 | 0.1% | 7,158 | 0.9% | 2,557 | 0.3% | 2,061 | 0.3% | 1,136 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 11,355 | 1.5% | 763,014 | 11,682 | 1,090,344 | |

| Ust-Orda Buryat Autonomous Okrug | 21,827 | 37.0% | 23,604 | 40.0% | 5,041 | 8.5% | 2,335 | 4.0% | 2,691 | 4.6% | 107 | 0.2% | 663 | 1.1% | 419 | 0.7% | 161 | 0.3% | 98 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 811 | 1.4% | 57,757 | 1,244 | 82,940 | |

| Vladimir Oblast | 270,736 | 30.9% | 261,808 | 29.9% | 174,490 | 19.9% | 64,783 | 7.4% | 58,774 | 6.7% | 1,591 | 0.2% | 6,980 | 0.8% | 3,618 | 0.4% | 3,923 | 0.5% | 1,957 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 14,222 | 1.6% | 862,882 | 13,592 | 1,243,738 | |

| Volgograd Oblast | 411,822 | 28.6% | 576,802 | 40.0% | 196,609 | 13.7% | 92,623 | 6.4% | 94,418 | 6.6% | 1,995 | 0.1% | 19,237 | 1.3% | 6,055 | 0.4% | 3,543 | 0.3% | 2,572 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 19,832 | 1.4% | 1,425,508 | 14,897 | 2,003,793 | |

| Vologda Oblast | 306,663 | 45.2% | 126,665 | 18.7% | 119,719 | 17.6% | 40,200 | 5.9% | 48,338 | 7.1% | 1,320 | 0.2% | 5,894 | 0.9% | 4,633 | 0.7% | 2,295 | 0.3% | 1,302 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 14,799 | 2.2% | 671,828 | 7,054 | 983,482 | |

| Voronezh Oblast | 319,402 | 22.7% | 641,540 | 45.5% | 246,234 | 17.5% | 62,458 | 4.4% | 82,429 | 5.8% | 1,846 | 0.1% | 10,767 | 0.8% | 4,316 | 0.3% | 2,247 | 0.2% | 2,428 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 19,982 | 1.4% | 1,393,649 | 16,799 | 1,963,015 | |

| Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 104,486 | 55.3% | 17,360 | 9.2% | 29,789 | 15.8% | 11,824 | 6.3% | 14,304 | 7.6% | 352 | 0.2% | 2,975 | 1.6% | 1,286 | 0.7% | 1,086 | 0.6% | 315 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 2,713 | 1.43% | 186,490 | 2,577 | 296,650 | |

| Yaroslavl Oblast | 260,919 | 32.9% | 144,188 | 18.2% | 245,613 | 31.0% | 65,886 | 8.3% | 38,380 | 4.8% | 1,157 | 0.2% | 4,896 | 0.6% | 3,338 | 0.4% | 4,113 | 0.5% | 1,464 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 12,865 | 1.6% | 782,819 | 9,462 | 1,098,249 | |

| Sources: Central Election Commission International Republican Institute;Electoral Geography 2.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Second round results by federal subject

| Federal subjects with a plurality of vote for Yeltsin |

| Federal subjects with a plurality of vote for Zyuganov |

| Boris Yeltsin Independent |

Gennady Zyuganov CPRF |

Against all | Total | Invalid ballots | Registered voters/turnout | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal subject | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||||||||||||||||||

| Adygea | 76,146 | 34.5% | 133,665 | 60.5% | 7,575 | 3.4% | 217,386 | 3,435 | 340,508 | 64.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Agin-Buryat Autonomous Okrug | 14,405 | 49.2% | 13,839 | 47.2% | 599 | 28,843 | 457 | 44,231 | 66.3% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Altai Krai | 505,270 | 38.6% | 727,548 | 55.5% | 65,029 | 5.0% | 1,297,847 | 12,605 | 1,953,564 | 67.1% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Altai Republic | 40,026 | 43.0% | 48,057 | 51.7% | 3,527 | 91,610 | 1,385 | 131,097 | 71.0% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Amur Oblast | 186,867 | 40.7% | 243,823 | 53.1% | 24,993 | 5.4% | 455,683 | 3,733 | 700,393 | 65.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Arkhangelsk Oblast | 448,477 | 63.9% | 194,704 | 27.8% | 52,315 | 7.5% | 695,496 | 6,215 | 1,058,566 | 66.4.% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Astrakhan Oblast | 229,153 | 47.3% | 233,738 | 48.2% | 21,623 | 4.5% | 484,514 | 4,567 | 735,471 | 66.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bashkortostan | 1,170,774 | 52.2% | 990,148 | 44.1% | 83,484 | 3.7% | 2,244,406 | 50,577 | 2,851,338 | 80.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Belgorod Oblast | 300,481 | 36.3% | 485,024 | 57.6% | 33,850 | 4.1% | 819,355 | 8,779 | 1,098,946 | 75.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bryansk Oblast | 286,515 | 36.3% | 467,552 | 59.2% | 27,173 | 3.4% | 781,240 | 8,186 | 1,114,079 | 70.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Buryatia | 192,933 | 45.3% | 210,791 | 49.5% | 16,036 | 3.8% | 419,760 | 6,108 | 689,933 | 61.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chechnya | 275,455 | 73.4% | 80,877 | 21.5% | 15,184 | 4.0% | 371,516 | 3,887 | 503,671 | 74.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chelyabinsk Oblast | 1,081,811 | 58.5% | 646,306 | 35.0% | 98,015 | 1,826,132 | 22,594 | 2,667,324 | 69.5% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chita Oblast | 209,803 | 40.9% | 269,459 | 52.5% | 27,348 | 506,510 | 6,553 | 827,378 | 62.1% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chukotka Autonomous Okrug | 30,009 | 74.3% | 7,730 | 19.1% | 2,435 | 6.0% | 40,174 | 223 | 52,771 | 76.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chuvashia | 205,959 | 31.8% | 405,129 | 62.6% | 21,614 | 632,702 | 14,564 | 962,349 | 67.3% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Dagestan | 471,231 | 53.1% | 401,069 | 44.3% | 7,423 | 0.8% | 879,723 | 15,263 | 1,208,348 | 73.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Evenk Autonomous Okrug | 5,273 | 65.8% | 2,272 | 28.3% | 409 | 5.1% | 7,954 | 65 | 12,852 | 62.3% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ingushetia | 75,768 | 79.8% | 14,738 | 15.5% | 3,136 | 3.3% | 93,642 | 1,308 | 113,849 | 83.5% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Irkutsk Oblast | 578,469 | 52.6% | 437,105 | 39.8% | 69,087 | 1,084,661 | 14,331 | 1,802,839 | 61.1% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ivanovo Oblast | 349,433 | 53.2% | 256,556 | 39.1% | 45,408 | 6.9% | 651,407 | 5,392 | 957,311 | 68.7% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Jewish Autonomous Oblast | 45,791 | 49.4% | 40,464 | 43.7% | 5,333 | 91,588 | 1,057 | 141,466 | 65.6% | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kabardino-Balkaria | 259,313 | 63.6% | 135,287 | 33.2% | 7,952 | 2.0% | 402,552 | 5,133 | 513,132 | 79.7% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kaliningrad Oblast | 289,088 | 57.7% | 177,077 | 35.3% | 30,770 | 6.1% | 496,935 | 4,144 | 724,343 | 69.3% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kalmykia | 103,515 | 70.3% | 39,354 | 26.7% | 2,919 | 2.0% | 145,788 | 1,523 | 200,806 | 73.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kaluga Oblast | 290,595 | 49.0% | 272,592 | 46.0% | 29,800 | 5.0% | 592,987 | 5,036 | 839,267 | 71.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kamchatka Krai | 99,980 | 62.3% | 47,664 | 29.7% | 12,901 | 8.0% | 160,454 | 1,210 | 274,830 | 58.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Karachay-Cherkessia | 109,747 | 50.7% | 101,379 | 46.9% | 5,286 | 2.4% | 216,412 | 3,546 | 296,321 | 74.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Karelia | 251,205 | 66.8% | 100,104 | 26.6% | 25,025 | 6.6% | 376,334 | 3,059 | 580,909 | 65.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kemerovo Oblast | 567,761 | 42.0% | 704,322 | 52.1% | 80,109 | 5.9% | 1,352,182 | 14,501 | 2,169,590 | 63.1% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Khabarovsk Krai | 430,870 | 59.4% | 246,378 | 34.0% | 47,765 | 6.6% | 725,013 | 5,539 | 1,106,030 | 66.2% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Khakassia | 116,729 | 116,644 | 11,842 | 491,550 | 4,877 | 814,347 | 62.5% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug | 368,650 | 75.0% | 100,303 | 20.4% | 22,707 | 4.6% | 491,660 | 4,877 | 814,664 | 61.1% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kirov Oblast | 425,465 | 51.2% | 348,835 | 42.0% | 56,929 | 6.8% | 831,229 | 7,887 | 1,201,171 | 69.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Komi Republic | 308,250 | 65.0% | 134,224 | 28.3% | 31,577 | 6.7% | 474,051 | 4,889 | 791,846 | 60.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Komi-Permyak Autonomous Okrug | 44,136 | 63.6% | 22,908 | 33.0% | 2,384 | 3.4% | 69,428 | 879 | 102,567 | 68.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Koryak Autonomous Okrug | 10,364 | 70.6% | 3,401 | 23.2% | 915 | 6.2% | 14,680 | 173 | 21,889 | 67.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kostroma Oblast | 208,153 | 50.3% | 178,238 | 43.0% | 27,709 | 6.7% | 414,110 | 3,358 | 598,475 | 69.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Krasnodar Krai | 1,116,007 | 44.3% | 1,308,765 | 51.9% | 96,752 | 3.8% | 2,521,524 | 20,997 | 3,904,612 | 65.2% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Krasnoyarsk Krai | 764,633 | 53.9% | 572,555 | 40.4% | 80,834 | 5.7% | 1,418,022 | 12,987 | 2,145,968 | 66.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kurgan Oblast | 246,097 | 43.8% | 284,731 | 44.3% | 30,668 | 11.9% | 561,495 | 5,436 | 786,547 | 72.1% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kursk Oblast | 258,183 | 36.8% | 419,756 | 59.7% | 24,699 | 3.5% | 702,638 | 9,739 | 1,010,449 | 70.5% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Leningrad Oblast | 570,702 | 61.8% | 300,501 | 32.5% | 52,915 | 5.7% | 924,118 | 6,123 | 1,344,260 | 69.3% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Lipetsk Oblast | 259,529 | 39.0% | 378,393 | 56.9% | 27,217 | 4.1% | 665,139 | 6,947 | 948,106 | 71.0% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Magadan Oblast | 65,965 | 64.0% | 28,573 | 27.7% | 8,528 | 8.3% | 103,066 | 703 | 166,632 | 62.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mari El | 154,301 | 41.3% | 199,872 | 53.5% | 19,628 | 5.2% | 373,801 | 4,904 | 550,715 | 68.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mordovia | 238,441 | 47.3% | 249,451 | 49.8% | 16,328 | 2.9% | 504,220 | 18,283 | 692,878 | 75.5% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Moscow | 3,629,464 | 77.8% | 842,092 | 18.1% | 193,785 | 4.1% | 4,665,341 | 30,767 | 6,672,788 | 70.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Moscow Oblast | 2,462,197 | 64.7% | 1,146,348 | 30.1% | 194,639 | 5.2% | 3,803,184 | 31,745 | 5,417,224 | 70.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Murmansk Oblast | 303,401 | 70.6% | 94,664 | 22.0% | 31,851 | 7.4% | 429,916 | 2,726 | 763,877 | 56.7% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 11,919 | 62.3% | 5,596 | 29.2% | 1,625 | 8.5% | 19,140 | 229 | 28,606 | 67.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Nizhny Novgorod Oblast | 967,307 | 791,738 | 91,315 | 2,860,893 | 19,108 | 1,850,360 | 65.5% | |||||||||||||||||||||

| North Ossetia-Alania | 133,748 | 43.8% | 164,308 | 53.8% | 7,317 | 2.4% | 305,373 | 5,691 | 441,614 | 70.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Novgorod Oblast | 244,129 | 59.6% | 140,329 | 34.2% | 25,371 | 6.2% | 409,829 | 2,999 | 584,018 | 70.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Novosibirsk Oblast | 596,564 | 43.7% | 666,858 | 48.9% | 85,698 | 6.3% | 1,349,120 | 14,673 | 2,039,828 | 67.0% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Omsk Oblast | 514,384 | 46.8% | 528,562 | 48.1% | 57,177 | 5.1% | 1,100,123 | 12,464 | 1,525,989 | 73.0% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Orenburg Oblast | 160,162 | 32.3% | 316,213 | 63.8% | 1,151 | 3.9% | 495,526 | 4,180 | 686,945 | 67.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Oryol Oblast | 441,163 | 42.1% | 583,090 | 55.7% | 45,423 | 2.2% | 1,047,660 | 11,408 | 1,595,245 | 62.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Penza Oblast | 299,780 | 37.3% | 497,773 | 61.9% | 38,734 | 0.8% | 804,316 | 8,118 | 1,168,541 | 72.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Perm Krai | 933,294 | 71.6% | 310,546 | 23.8% | 60,109 | 4.6% | 1,303,949 | 13,446 | 2,022,676 | 65.2% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Primorsky Krai | 524,428 | 52.8% | 395,463 | 39.8% | 74,206 | 7.4% | 994,107 | 9,300 | 1,586,108 | 63.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pskov Oblast | 217,500 | 45.6% | 231,201 | 48.5% | 28,212 | 5.9% | 476,913 | 3,932 | 656,216 | 73.3% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rostov Oblast | 1,219,594 | 51.1% | 1,063,135 | 44.6% | 102,293 | 4.3% | 2,385,022 | 21,740 | 3,295,420 | 73.2% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ryazan Oblast | 313,087 | 43.0% | 379,626 | 52.1% | 36,175 | 4.9% | 728,888 | 65,75 | 1,031,496 | 71.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sakha Republic | 274,570 | 64.7% | 126,888 | 29.9% | 17,293 | 4.1% | 428,752 | 5,979 | 601,252 | 70.7% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sakhalin Oblast | 152,795 | 54.0% | 111,085 | 39.2% | 19,578 | 6.8% | 283,458 | 2,792 | 461,110 | 62.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Samara Oblast | 910,134 | 52.4% | 747,946 | 43.1% | 79,083 | 4.5% | 1,737,163 | 14,781 | 2,455,498 | 71.5% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Saratov Oblast | 664,799 | 44.6% | 753,173 | 50.5% | 73,309 | 4.9% | 1,491,281 | 16,910 | 2,042,831 | 73.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Smolensk Oblast | 234,125 | 38.5% | 345,190 | 56.7% | 29,352 | 4.8% | 608,667 | 4,990 | 887,257 | 69.2% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Stavropol Krai | 548,749 | 41.3% | 722,889 | 54.4% | 56,324 | 4.3% | 1,327,962 | 12,576 | 1,870,996 | 71.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Saint Petersburg | 1,759,950 | 74.1% | 502,553 | 21.2% | 112,723 | 4.7% | 2,375,206 | 7,571 | 3,659,544 | 65.3% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sverdlovsk Oblast | 1,726,549 | 77.5% | 401,515 | 18.0% | 98,563 | 4.5% | 2,226,627 | 17,934 | 3,452,336 | 65.1% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tambov Oblast | 217,499 | 32.9% | 419,639 | 63.4% | 24,705 | 3.7% | 661,843 | 5,882 | 980,607 | 68.1% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tatarstan | 1,253,121 | 63.1% | 658,782 | 33.2% | 74,178 | 3.7% | 1,986,081 | 53,145 | 2,632,389 | 77.5% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Taymyr Autonomous Okrug | 12,787 | 72.2% | 3,851 | 21.7% | 1,082 | 6.1% | 17,720 | 135 | 28,920 | 61.8% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tomsk Oblast | 290,199 | 59.8% | 165,241 | 34.1% | 29,667 | 6.1% | 485,107 | 5,328 | 744,010 | 66.01 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tula Oblast | 536,783 | 53.0% | 421,169 | 41.6% | 54,934 | 5.4% | 1,012,866 | 11,042 | 1,440,510 | 71.2% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tuva | 73,113 | 64.8% | 37,227 | 33.0% | 2,433 | 2.2% | 112,763 | 3,160 | 171,742 | 67.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tver Oblast | 455,731 | 50.5% | 396,627 | 44.0% | 40,877 | 5.5% | 902,235 | 6,387 | 1,268,488 | 71.7% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Tyumen Oblast | 343,391 | 56.0% | 234,743 | 38.6% | 30,539 | 5.4% | 608,673 | 6,528 | 915,585 | 67.3% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Udmurtia | 392,551 | 53.4% | 302,649 | 41.2% | 40,302 | 5.4% | 735,502 | 7,513 | 1,156,145 | 64.3% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ulyanovsk Oblast | 286,860 | 38.1% | 426,778 | 57.0% | 35,168 | 4.9% | 748,806 | 9,460 | 1,093,057 | 69.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ust-Orda Buryat Autonomous Okrug | 29,014 | 49.5% | 28,016 | 47.8% | 1,610 | 2.7% | 58,640 | 974 | 82,814 | 72.0% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Vladimir Oblast | 421,352 | 52.1% | 342,077 | 42.3% | 46,057 | 5.6% | 809,486 | 7,661 | 1,250,544 | 65.4% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Volgograd Oblast | 616,368 | 44.2% | 703,784 | 50.5% | 63,496 | 4.5% | 1,383,648 | 10,546 | 2,006,436 | 69.6% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Vologda Oblast | 426,532 | 64.4% | 189,989 | 28.7% | 45,558 | 6.9% | 661,979 | 4,814 | 989,121 | 67.5% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Voronezh Oblast | 501,114 | 37.3% | 781,260 | 58.1% | 62,022 | 4.6% | 1,344,396 | 11,052 | 1,968,924 | 68.9% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug | 467,896 | 60.2% | 243,526 | 31.4% | 55,520 | 8.4% | 776,932 | 6,004 | 1,100,070 | 66.2% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yaroslavl Oblast | 467,896 | 60.0% | 243,526 | 31.8% | 55,510 | 8.2% | 766,932 | 6,004 | 1,100,080 | 70.3% | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sources: Central Election Commission; Central Election Commission; Central Election Commission; International Republican Institute;Electoral Geography 2.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Red Belt (Russia), term describing federal subjects that had strong support for Zyuganov's Communist Party of the Russian Federation

- Third force (1996 Russian presidential election), a proposed electoral bloc

References

- ↑ "Report on the Russian Presidential Elections March 26, 2000" (PDF). CSCE. 2000.

- 1 2 Depoy, Eric (1996). "Boris Yeltsin and the 1996 Russian Presidential Election". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 26 (4): 1140–1164. JSTOR 27551676.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 David M. Kotz. Russia's Path From Gorbachev To Putin. pp. 260–264.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 McFaul, Michael (1997). Russia's 1996 Presidential Election: The End of Polarized Politics. Stanford University in Stanford, California: Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 9780817995027.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Russian Election Watch, May 9, 1996". 9 May 1996. Archived from the original on 4 January 2001. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Выдвижение и регистрация кандидатов". 1996. Archived from the original on 9 October 1999. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ↑ "Newsline – March 5, 1996". www.rferl.org. RadioFreeEuroupe/RadioLiberty. 5 March 1996. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 O'Connor, Eileen (6 June 1996). "Russia's Ross Perot". www.cnn.com. CNN. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Справочник Вся Дума. — Коммерсант-Власть, 25 January 2000. — № 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Svyatoslav Fedorov". www.cs.ccsu.edu. CCSU. 1996. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ Solovei, Valery (1996). "Strategies of the Main Presidential Candidates" (PDF). Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Yasmann, Victor (13 June 1991). "FEDOROV: "REVIVED RUSSIA WILL SURPASS US AND JAPAN"". www.friends-partners.org. Radio Free Europe/ Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 23 September 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2018.

- 1 2 "Russian Election Watch, February 9, 1996". 9 February 1996. Archived from the original on 29 January 2000. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ↑ McFaul, Michael (1997). Russia's 1996 Presidential Election: The End of Polarized Politics. Stanford University in Stanford, California: Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 9780817995027.

- ↑ Smith, Kathleen E. (2002). Mythmaking in the New Russia. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 The 1996 Russian presidential election / Jerry F. Hough, Evelyn Davidheiser, Susan Goodrich Lehmann. Brookings occasional papers.

- 1 2 Obshchaya Gazetta 5/18/95

- ↑ Witte, John; Bourdeaux, Michael. Proselytism and Orthodoxy in Russia: The New War for Souls. p. 127.

- 1 2 "Russian Election Watch, April 18, 1996". 18 April 1996. Archived from the original on 5 December 2000. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "Russian Presidential Elections". www.cs.ccsu.edu. CCSU. 1996. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- ↑ Bohlen, Celestine (2 March 1999). "Russia's Stubborn Strains of Anti-Semitism". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 "Newsline – May 30, 1996". www.rferl. RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 30 May 1996. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ↑ Предвыборная программа кандидата на пост президента России Юрия Власова

- ↑ Rus'bez vozhdya (Soyuz zhurnalistov, Vororonzeh, 1995 pages 97–104, 495–512)

- ↑ Shenfield, Stephen (8 July 2016). Russian Fascism: Traditions, Tendencies and Movements: Traditions, Tendencies and Movements. Routledge.

- 1 2 White, David (2006). The Russian Democratic Party Yabloko: Opposition in a Managed Democracy. Ashgate Publishing, LTD.

- ↑ Law-and-Order Candidate Finds Himself in Role of Kingmaker, by CAROL J. WILLIAMS, Los Angeles Times, 18 June 1996

- ↑ Kartsev, Vladimir; Bludeau, Todd (1995). !Zhirinovsky!. New York: Columbia University Press.

- 1 2 3 Nichols, Thomas S. (1999). The Russian Presidency, Society and Politics in the Second Russian Republic. St. Martin’s Press.

- ↑ "Russia Presidential Election Observation Report" (PDF). www.iri.org. International Republican Institute. 1996. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Assessing Russia's Democratic Presidential Election".

- 1 2 3 "Report on the Election of the President of the Russian Federation". www.oscepa.org. OSCE. 1996. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- 1 2 3 "CNN - Yeltsin leads election poll - April 22, 1996". CNN.

- ↑ "Newsline – June 27, 1996". www.rferl.org. RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 27 June 1996. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Russian Election Watch, Aug. 1, 1996". 1 August 1996. Archived from the original on 28 January 2000. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ↑ Борис-боец // The New York Times, 30 апреля 2007

- ↑ Treisman, Daniel (November–December 2000). "Blaming Russia First". Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 3 August 2004. Retrieved 8 July 2004.

- ↑ See, e.g., Sutela, Pekka (1994). "Insider Privatization in Russia: Speculations on Systemic Changes". Europe-Asia Studies. 46 (3): 420–21. doi:10.1080/09668139408412171.

- ↑ Скандал вокруг ВГТРК разрастается. Госдума намерена вызвать Сагалаева на ковер

- ↑ "Report on the Election of the President of the Russian Federation". www.oscepa.org. OSCE. 1996. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Brudny, Yitzhak M (1997). "In pursuit of the Russian presidency: Why and how Yeltsin won the 1996 presidential election". Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 30 (3): 255–275. doi:10.1016/S0967-067X(97)00007-X.

- ↑ Englund, William (11 June 2011). "A defining moment in the Soviet breakup". Washington Post. Retrieved 12 September 2018.

- ↑ "Russian Election Watch, May 15, 1996". 15 May 1996. Archived from the original on 27 January 2000. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ↑ Gel'man, Vladimir (2015). Authoritarian Russia: Analyzing Post-Soviet Regime Changes. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8229-8093-3.

- ↑ "The Election of President of the Russian Federation 1996: A Technical Analysis" (PDF). www.ifes.org. International Foundation for Electoral Systems. 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- ↑ "07.08.1996 ПОСТАНОВЛЕНИЕ ЦЕНТРАЛЬНОЙ ИЗБИРАТЕЛЬНОЙ КОМИССИИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ". www.cikrf.ru. Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation. 7 August 1996. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ↑ "19.07.1996 ПОСТАНОВЛЕНИЕ ЦЕНТРАЛЬНОЙ ИЗБИРАТЕЛЬНОЙ КОМИССИИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ". www.cikrf.ru. Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation. 19 July 1996. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- 1 2 "Russian Elections: An Oxymoron of Democracy" (PDF). CALTECH/MIT VOTING TECHNOLOGY PROJECT. March 2008. pp. 2–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- 1 2 M. Steven Fish (2005). Democracy Derailed in Russia: The Failure of Open Politics. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9781139446853.

- 1 2 Ordeshook, Peter; Myagkov, Misha (March 2008). "Russian Elections: An Oxymoron of Democracy" (PDF). www.caltech.edu. Caltech. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ "06.11.1997 ПОСТАНОВЛЕНИЕ ЦЕНТРАЛЬНОЙ ИЗБИРАТЕЛЬНОЙ КОМИССИИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ". www.cikrf.ru. Central Election Commission of the Russian Federation. 6 November 1997. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- 1 2 "Rewriting Russian History: Did Boris Yeltsin Steal the 1996 Presidential Election?". Time. 24 February 2012.

- ↑ Jerry F. Hough (2001). The Logic of Economic Reform in Russia. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 186–7. ISBN 978-0815798590.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Ross, Cameron (19 July 2013). Federalism and Democratisation in Russia. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- ↑ Gallagher, Tom (8 July 2017). "One Fait Accompli After Another: Mikhail Gorbachev on the New Russia". www.lareviewofbooks.org. Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ↑ "Arnie's spin doctors spun for Yeltsin too". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ↑ TIME Exclusive Yanks To The Rescue, Time. July 1996.

- ↑ Stanley, Alessandra (9 July 1996). "Moscow Journal;The Americans Who Saved Yeltsin (Or Did They?)". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ↑ McFaul, Michael (21 July 1996). "Yanks Brag, Press Bites". The Weekly Standard. Archived from the original on 22 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ↑ Hockstader, Lee; Hoffman, David (7 July 1996). "Yeltsin Campaign Rose from Tears to Triumph". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ↑ Bershidsky, Leonid (31 August 2018). "Bill Clinton and Boris Yeltsin Missed Historic Opportunity". www.bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- 1 2 Eckel, Mike (30 August 2018). "Putin's 'A Solid Man': Declassified Memos Offer Window into Yeltsin-Clinton Relationship". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- ↑ Lantz, Matthew (1997). The Russian Election Compendium. Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Shimer, David (26 June 2020). "Election meddling in Russia: When Boris Yeltsin asked Bill Clinton for help". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286.

- ↑ Swarns, Rachel L. (23 January 1997). "Unlikely Meeting of Minds: Lebed Meets The Donald". The New York Times.

- ↑ Singer, Mark (12 May 1997). "Searching for Trump's Soul". The New Yorker.

- ↑ Jones, Owen (5 January 2017). "Americans can spot election meddling because they've been doing it for years". The Guardian.

- ↑ Agrawal, Nina (21 December 2016). "The U.S. is no stranger to interfering in the elections of other countries". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Nohlen, D; Stöver, P (2010). Elections in Europe: A data handbook. p. 1642. ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7.

- ↑ Timothy J. Colton (2000). Transitional Citizens: Voters and What Influences Them in the New Russia. Harvard University Press. pp. 234–5. ISBN 9780674029804.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)