| S-200 Angara/Vega/Dubna SA-5 Gammon | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) S-200V missile on its launcher | |

| Type | Strategic SAM system |

| Place of origin | Soviet Union |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1967–present |

| Used by | See list of present and former operators |

| Wars | First Libyan Civil War Syrian civil war Russo-Ukrainian War[1] |

| Production history | |

| Designer | KB-1 design bureau (system), GSKB Spetsmash (launcher)[2] |

| Designed | 1964 |

| Variants | S-200A, S-200V, S-200M, S-200VE, S-200D, S-200C |

| Specifications | |

Guidance system | Semi-active radar homing |

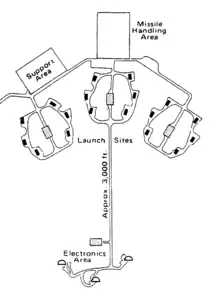

The NPO Almaz S-200 Angara/Vega/Dubna (Russian: С-200 Ангара/Вега/Дубна), NATO reporting name SA-5 Gammon (initially Tallinn),[3] is a long-range, high-altitude surface-to-air missile (SAM) system developed by the Soviet Union in the 1960s to defend large areas from high-altitude bombers or other targets. In Soviet service, these systems were deployed primarily on the battalion level, with six launchers and a fire control radar.

The S-200 can be linked to other longer-range radar systems.

Background

_missile_of_surface-to-air_missile_system_%C2%ABDal%C2%BB_in_Military-historical_Museum_of_Artillery%252C_Engineer_and_Signal_Corps_in_Saint-Petersburg%252C_Russia.jpg.webp)

After trials of the S-25 Berkut in 1955, the Soviet Union started development of the RS-25 Dal long-range missile system with the V-400/5V11 missile. It was initially assigned the "SA-5" designation in the West[4] and codenamed "Griffon", but the project was abandoned in 1964.[5] The SA-5 designation was then assigned to the S-200.

Description

The S-200 surface-to-air missile system was designed for the defense of the most important administrative, industrial and military installations from all types of air attack. The S-200 is an all-weather system that can be operated in various climatic conditions.[6]

The first S-200 operational regiments were deployed in 1966 with 18 sites and 342 launchers in service by the end of the year. By 1968 there were 40 sites, and by 1969 there were 60 sites. The growth in numbers then gradually increased throughout the 1970s (1,100 launchers)[7] and early 1980s until the peak of 130[2] sites and 2,030 launchers was reached in 1980–1990.[7]

Variants

- S-200A "Angara" (Russian: С-200А, NATO reporting name SA-5a), with the V-860/5V21 or V-860P/5V21A missile, introduced in 1967, range 160 km (99 mi), ceiling 20.1 km (12.5 mi).[8]

- S-200V "Vega"[lower-alpha 1] (Russian: С-200В, NATO reporting name SA-5b), with the V-860PV/5V21P or 5V28V missiles, introduced in 1970, range 250 km (160 mi), ceiling 29.2 km (18.1 mi).[8] With the V-870 missile, range increased to 280 km (170 mi) and ceiling to 40 km (25 mi).[8]

- S-200M "Vega-M"[lower-alpha 1] (Russian: С-200М, NATO reporting name SA-5b), with the V-880/5V28 or V-880N/5V28N missiles, introduced 1970,[8] range 300 km (190 mi), ceiling 29 km (18 mi). The V-880N/5V28N was the first missile for the S-200 which could be equipped with a nuclear warhead, with the "N" in the designation standing for "nuclear".[8]

- S-200VE "Vega-E"[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] (Russian: С-200ВЭ, NATO reporting name SA-5b), with the V-880E/5V28E missile, export version with high-explosive warhead only, introduced 1973, range 240 km (150 mi), ceiling 40.8 km (25.4 mi).[10]

- S-200D "Dubna" (Russian: С-200Д, NATO reporting name SA-5c), with the 5V25V, V-880M/5V28M, and V-880MN/5V28MN missiles, introduced in 1976, range 300 km (190 mi),[10] ceiling 40 km (25 mi).[11] The V-880MN/5V28MN were equipped with a 5 kiloton nuclear warhead.[10]

- S-200C "Vega",[lower-alpha 1] a Polish evolution of the S-200VE, resulting from a refit undertaken between 1999 and 2002.[12]

The Iranian air defense force has implemented several improvements on their S-200 systems such as using solid state parts and removing restrictions on working time. They reportedly destroyed a UAV target beyond 100 km range in a military drill in recent years.[13] They use two new solid propellant missiles named Sayyad-2 and Sayyad-3, via interface systems Talash-2 and Talash-3 in cooperation with S-200 system. These missiles can cover medium and long ranges at high altitudes.[14][15] Iran claims to have developed a mobile launcher for the system.[16]

The command post of the S-300 system (SA-20/SA-20A/SA-20B) can manage the elements of the S-200 and S-300 in any combination.[17][18] The S-200 Dubna missile complex can be controlled by the S-300's command post,[18] and the S-300 missile complex can be controlled[19] by the S-400 command post[20] or through a higher-level command post (Organize Use PVO 73N6 "Baikal-1").[21]

Radar

The fire control radar of the S-200 system is the 5N62 (NATO reporting name: Square Pair) H band[22] continuous wave radar, and is used for both the tracking of targets and their illumination. The 5N62V variant could track larger targets like strategic bombers at 450 km (280 mi), smaller aircraft like fighter-bombers at 300 km (190 mi), and cruise missiles at c. 170 km (110 mi).[23] The 5N62 had two main components, the K-1 and K-2 "cabins", with the former containing the antenna. The K-1 could rotate around its own axis at 15 degrees per second, completing a full turn in 24 seconds and would make elevation adjustments at 5.5 degrees per second.[24] A K-1 in assembled state weighed 30 tonnes (66,000 lb).[24] The K-2 cabin contained the command post and weighed about 25 tonnes (55,000 lb).[25]

Initial detection of targets was conducted by a P-14/5N84A (NATO: "Tall King C") A band early warning radar, operating in the 150–170 MHz range at 3–6 RPM,[26] with a PRV-17 (NATO: "Odd Group") height finding radar assisting in determining the target's altitude.[27]

The P-35 (NATO: Bar Lock) E/F band radar could also be associated with the S-200.[22]

Missiles

| 5V21 | |

|---|---|

| Type | Surface-to-air missile |

| Place of origin | Soviet Union |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1967–present |

| Used by | See list of operators |

| Production history | |

| Designer | OKB-2 design bureau (missile), SKB-35 bureau (avionics), NII-125 research institute (solid rocket fuel) |

| Variants | 5V21, 5V28, 5V28V |

| Specifications (5V28V[2]) | |

| Mass | 7,100 kg (15,700 lb) |

| Length | 10,800 mm (35.4 ft) |

| Warhead | Frag-HE |

| Warhead weight | 217 kg (478 lb) |

Detonation mechanism | proximity and command fusing[22] |

| Propellant | dual-thrust liquid-fueled rocket motor |

Operational range | 300 kilometres (190 mi)[22] |

| Flight altitude | 40,000 metres (130,000 ft) |

| Boost time | 4 solid-fueled strap-on rocket boosters |

| Maximum speed | Mach 4 (4,900 km/h; 3,000 mph)[22] |

Guidance system | semi-active radar homing seeker head |

Each missile is launched by 4 solid-fueled strap-on rocket boosters.[28] After they burn out and drop away (between 3 and 5.1 seconds from launch) it fires a 5D67 liquid fueled sustainer rocket engine (for 51–150 seconds) which burns a fuel called TG-02 Samin (50% xylidine and 50% triethylamine), oxidized by an agent called AK-27P (red fuming nitric acid enriched with nitrogen oxides, phosphoric acid and hydrofluoric acid).[29] Maximum range is between 150 km (81 nmi) and 300 km (160 nmi), depending on the model.[30] The missile uses radio illumination mid-course correction to fly towards the target with a terminal semi-active radar homing phase. Maximum missile speed is 2500 m/s and maximum target speed is around Mach 6 for new model and Mach 4 for earlier model. Effective altitude is 300 m (980 ft) to 20,000 m (66,000 ft) for early models and up to 35,000 m (115,000 ft) for later models. The warhead is either 217 kg (478 lb) high-explosive fragmentation (16,000 × 2 g fragmentation pellets and 21,000 × 3.5 g pellets) triggered by radar proximity fuse or command signal, or a 25 kt nuclear warhead triggered by command signal only. Each missile weighs around 7,108 kg (15,670 lb) at takeoff.[30]

Operational history

Ukraine

A Ukrainian S-200 operated by the Ukrainian military during a Ukrainian training exercise fired on a Tupolev Tu-154 passenger aircraft flying from Tel Aviv to Novosibirsk, Siberia Airlines Flight 1812. The airliner was destroyed over the Black Sea on 4 October 2001, killing all 78 people on board.[31]

Ukrainian armed forces possibly used S-200 missiles in 2023, during the Russian invasion, to attack Russian positions in Bryansk Oblast and Crimea.[32][33] It was reported that the missiles were used in an attack on the Crimean Bridge.[34]

Libya

Starting in 1985, Libya received a number of S-200 missile systems.[35] In the following months, Libyan forces fired a number of S-200 missiles on different occasions at US fighter-bombers, missing them.[36] In the USSR, three organizations (CDB Almaz, a test site and a research institute of the Ministry of Defense) conducted computer simulation of the battle, which gave the probability of hitting each of the air targets (3) in the range from 96 to 99%.[37][38]

Syria

Starting in January 1983, Syria received supplies of S-200 missiles from the Soviet Union.[39][40] They were organized into two long range surface to air missile regiments, each composed of two battalions of two batteries each for a total of at least 24 launchers. Later in the 1980s, the Soviet Union agreed to supply a third regiment increasing the number of launchers to 40–50. Initially the missiles were manned by Soviet crews.[41] In April 1984, a U.S. intelligence report cited a Soviet official claiming that training of Syrian personnel was nearly complete and that the transfer of the system to Syrian control was to occur in the near future.[42]

During the initial years of the Syrian civil war, parts of the S-200 systems were occasionally spotted when Syrian Air Defense Force sites were overrun by rebel forces. Most notably radars, missiles and other equipment from S-200 systems was pictured in a state of disrepair when rebels overtook the air defense site in Eastern Ghouta in October 2012.[43][44] On 2 January 2017, the Syrian Army re-captured this air defense base.[45]

Starting with the Russian intervention in the civil war in late 2015, there were new efforts to restore some Syrian S-200 systems. Indeed, on 15 November 2016, the Russian defence minister confirmed that Russian forces repaired Syrian S-200s to operational status.[46] For example, in July 2016, the Syrian Army, with Russian assistance, rebuilt an S-200 site at Kweires airport, near Aleppo.[47] On September 12, 2016, the Israel Defense Forces confirmed that two Syrian S-200 missiles were fired at Israeli aircraft while they were on a mission inside Syrian airspace. The Syrian Defense Ministry claimed that an Israeli jet and a drone were shot down.[48] According to the IDF spokesman's office, the claims are "total lies," and "at no point was the safety of IDF aircraft compromised."[49]

On March 17, 2017, the Israeli Air Force attacked a number of Syrian armed forces targets near Palmyria in Syria. Four Israeli aircraft flew through Lebanese territory and launched Popeye stand off missiles with a range of 78 km toward Syrian territory. Syrian Air defence force (SyADF) after some time alerted one S-200V (SA-5) missile battery and tried to retaliate, 2 out of 4 attacking jets were illuminated with two 5N62 Fire Control Radars and missiles were fired on 2 targets, which then were over southern Lebanon.[50] During the action a number of Syrian S-200 missiles were fired at the Israeli aircraft.[51] One of the Syrian missiles, going ballistic after losing its target, was inbound to a populated area in Israel. The Israeli missile defense fired at least one Arrow missile which intercepted the incoming missile.[52] Two other S-200 missiles landed in other parts of Israel, having lost their target. According to ANNA News, Syria claimed that they had shot down one IAF F-16 aircraft and damaged another.[51] While the Syrian Defense Ministry claimed that an Israeli fighter jet was shot down, which was denied by Israel, Israeli defence minister Avigdor Lieberman threatened to destroy Syrian air defence systems after they fired ground-to-air missiles at Israeli warplanes carrying out strikes.[53] The Jordanian armed forces reported that parts of a missile fell in its territory. There were no casualties in Jordan.[54]

On October 16, 2017, a Syrian S-200 battery located around 50 kilometers east of Damascus fired a missile at an Israeli Air Force surveillance mission over Lebanon. The IAF responded by attacking the battery and destroying the fire control radar with four bombs.[55][56][57] Despite this, the Syrian Defense Ministry said in its statement that the air-defense forces "directly hit one of the jets, forcing [Israeli aircraft] to retreat." Israel said that no plane was hit.

On February 10, 2018, Israel launched an airstrike against targets in Syria with eight fighter aircraft as retaliation for a UAV incursion into Israeli airspace earlier in the day. Syrian air defenses succeeded in shooting down one of the Israeli jets, an F-16I Sufa, with an S-200 missile - this was the first Israeli jet to be shot down in combat since 1982.[58][59] The jet crashed in the Jezreel Valley, near Harduf.[60] Both the pilot and the navigator managed to eject; one was injured lightly, the other more seriously, but both survived and walked out of the hospital one week later.[58][61]

On 10 May 2018, Israeli Air Force launched Operation House of Cards against a number of Iranian and Syrian targets, claiming the destruction of a S-200 radar among different other targets.[62]

On September 17, 2018, a Russian Il-20M ELINT plane was shot down by a Syrian S-200 surface-to-air missile killing all the 15 servicemen on board. Four Israeli F-16 fighter jets attacked targets in Syria's Latakia with standoff missiles, after approaching from the Mediterranean Sea, a statement by the Russian defense ministry said on 18 September. “The Israeli pilots used the Russian plane as cover and set it up to be targeted by the Syrian air defense forces. As a consequence, the Il-20, which has radar cross-section much larger than the F-16, was shot down by an S-200 system missile,” the statement said. The Russian ministry stressed that the Israelis must have known that the Russian plane was present in the area, which didn't stop them from “the provocation”. Israel also failed to warn Russia about the planned operation in advance. The warning came a minute before the attack started, which “did not leave time to move the Russian plane to a safe area,” the statement said.[63] On 21 September, an Israeli delegation visiting Moscow stated that the Israeli attack formation did not use the Russian Il-20 as a shield during the attacks, while blaming the incident on the Syrian Air Defense Force which fired missiles for forty minutes while the Israeli attack formation had already left the area.[64][65] Russian President Vladimir Putin downplayed the incident saying that "it looks accidental, like a chain of tragic circumstances".[66]

On 1 July 2019, a stray S-200 missile fired from Syria, presumably during bombing raids there, hit Northern Cyprus. The missile hit the ground around 1:00 a.m. near the village of Taşkent, also known as Vouno, some 20 kilometers (12 miles) northeast of Nicosia. The missile that hit Cyprus was a Russian-made S-200, said the Turkish Cypriot foreign minister.[67]

On 22 April 2021, a stray S-200 missile exploded in the air some 30 kilometers from the Dimona nuclear reactor over Israel. The missile was fired from Dumayr, part of a salvo in response to Israeli jets conducting strikes on targets in the Syrian-controlled Golan Heights. Israeli air defenses tried to intercept the errant missile, but missed. Around an hour later, IDF said Israeli fighter jets struck the air defense battery which launched the missile.[68][69] On 19 August 2021, in response to an Israeli air raid, the Syrian Air Defense fired several Surface to Air missiles at attacking Israeli jets and missiles. One of them, an S-200 due to the range, exploded above the Dead Sea.[70] On 3 September 2021, Syrian army fired a missile over Tel Aviv which landed in Mediterranean Sea. In response to Syrian missile attack, the Israeli Air Force claim destroyed a battery of the Russian-made S-200 missile system of Syrian Army.[71]

Operators

Current operators

Bulgaria – [2][72] 12 launchers as of 2023.[73]

Bulgaria – [2][72] 12 launchers as of 2023.[73] Iran – 10 upgraded battalions in service as of 2023.[74][75][76] Will be replaced by Sayyad-2/Sayyad-3 (Talash) system.[6]

Iran – 10 upgraded battalions in service as of 2023.[74][75][76] Will be replaced by Sayyad-2/Sayyad-3 (Talash) system.[6] Kazakhstan – 1 battery (3 systems) as of 2023.[77]

Kazakhstan – 1 battery (3 systems) as of 2023.[77] North Korea – 4 battalions (2008).[2] 10 systems as of 2023, with the International Institute for Strategic Studies assessing that their "serviceability [...] is in doubt".[78]

North Korea – 4 battalions (2008).[2] 10 systems as of 2023, with the International Institute for Strategic Studies assessing that their "serviceability [...] is in doubt".[78] Poland – 1 squadron with S-200C as of 2023.[79][80][81] To be replaced by new anti aircraft systems Wisła (MIM-104 Patriot).[82]

Poland – 1 squadron with S-200C as of 2023.[79][80][81] To be replaced by new anti aircraft systems Wisła (MIM-104 Patriot).[82] Syria – 3 regiments in the Syrian Air Defense Force as of 2023.[83] 44 launchers in 2014.[84] Syrian Armed Forces constructed a new S-200 site at Kweires Airport, near Dahab, in July 2016.

Syria – 3 regiments in the Syrian Air Defense Force as of 2023.[83] 44 launchers in 2014.[84] Syrian Armed Forces constructed a new S-200 site at Kweires Airport, near Dahab, in July 2016. Turkmenistan – 2 batteries (12 systems) as of 2023.[85]

Turkmenistan – 2 batteries (12 systems) as of 2023.[85]

Potential operators

Ukraine – Ukraine's last S-200 division was reportedly retired on October 30, 2013,[86] but the weapon may have been brought back into service during the Russian invasion of Ukraine against land targets[87][33]

Ukraine – Ukraine's last S-200 division was reportedly retired on October 30, 2013,[86] but the weapon may have been brought back into service during the Russian invasion of Ukraine against land targets[87][33]

Former operators

Algeria – 10. No longer in service as of 2023.[88]

Algeria – 10. No longer in service as of 2023.[88] Azerbaijan – 1 battalion.

Azerbaijan – 1 battalion. Belarus – Approximately 4 battalions.

Belarus – Approximately 4 battalions. Czechoslovakia – 5 battalions, passed to Czech Republic.

Czechoslovakia – 5 battalions, passed to Czech Republic. Czech Republic – Inherited all Czechoslovak S-200 SAM systems, out of service since mid-1990s.[2]

Czech Republic – Inherited all Czechoslovak S-200 SAM systems, out of service since mid-1990s.[2] East Germany – 4 battalions S-200VE,[89] passed to unified Germany in 1990.[90]

East Germany – 4 battalions S-200VE,[89] passed to unified Germany in 1990.[90] Georgia[2]

Georgia[2] Germany – 4 battalions S-200VE from East Germany received during German reunification in 1990,[90] last site out of service in 1993[91]

Germany – 4 battalions S-200VE from East Germany received during German reunification in 1990,[90] last site out of service in 1993[91] Hungary – 1 battalion.[2]

Hungary – 1 battalion.[2] India - 2 battalions, retired in 2015.[92]

India - 2 battalions, retired in 2015.[92].svg.png.webp) Libyan Arab Jamahiriya – 8 battalions.[2]

Libyan Arab Jamahiriya – 8 battalions.[2] Moldova[2] – 1 battalion.

Moldova[2] – 1 battalion. Mongolia – The Mongolian People's Army operated 4 battalions as of 1985, but it is unlikely there are any operational as of 2011.[93]

Mongolia – The Mongolian People's Army operated 4 battalions as of 1985, but it is unlikely there are any operational as of 2011.[93] Myanmar[28] – No longer in service as of 2023.[94]

Myanmar[28] – No longer in service as of 2023.[94] Russia – No longer in service as of 2014.

Russia – No longer in service as of 2014. Soviet Union – Originally deployed with the ZA-PVO in the strategic air defense role. It was phased out starting in the 1980s and passed on to the successor states before the phasing out process could be completed.[2]

Soviet Union – Originally deployed with the ZA-PVO in the strategic air defense role. It was phased out starting in the 1980s and passed on to the successor states before the phasing out process could be completed.[2] Uzbekistan[2] – No longer in service as of 2023.[95]

Uzbekistan[2] – No longer in service as of 2023.[95]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 The Cyrillic character В is most commonly romanized as a Latin V, but some transliterations (such as the German Duden transliteration) use the Latin W.[9] To keep a consistent style, this article uses the common "V" romanization.

- ↑ Some German sources romanize the Cyrillic Э as Ä. The more common romanization as a Latin E is used in this article for consistency.

References

- ↑ "Russian air defenses intercept five Ukrainian S-200 missiles". Mehr News Agency. 10 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Almaz/Antei Concern of Air Defence S-200 Angara/Vega (SA-5 'Gammon') low to high-altitude surface-to-air missile system". Jane's Information Group. 2 April 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2008.

- ↑ Statement of Dr. John S. Foster, Director, Department of Research and Engineering, U.S. Department of Defense, April 15, 1970, p. 611.

- ↑ "Dal". Astronautix. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ↑ Werrell, Kenneth P. (2000). Hitting a Bullet with a Bullet: A History of Ballistic Missile Defense (PDF) (Report). Air University. p. 11 – via Defense Technical Information Center.

- 1 2 "Зенитный Ракетный Комплекс Большой Дальности С-200 (SA-5 Gammon)" [S-200 Long Range Anti-Aircraft Missile System] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 16 September 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Зенитная Ракетная Система С-200 (SA-5 Gammon)" [Anti-aircraft Missile System S-200]. pvo.guns.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kraus 2019, p. 17.

- ↑ Die Deutsche Rechtschreibung. Duden (in German). Vol. 1 (22nd ed.). Mannheim: Bibliographisches Institut. 2000. p. 118. ISBN 3411040122.

- 1 2 3 Kraus 2019, p. 18.

- ↑ "Зенитный ракетный комплекс С-200В Вега" [Anti-aircraft missile system S-200V Vega]. Ракетная техника (in Russian). Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ Pietrasieński, Jan; Rodzik, Dariusz; Bużantowicz, Witold (20 October 2021). "The Tactical and Technical Functioning Conditions of the S-200C Vega Missile System on the Modern Battlefield" (PDF). Safety & Defense. 7 (2): 80–89. doi:10.37105/sd.160. ISSN 2450-551X. S2CID 244993308.

- ↑ "اس-200 ایران؛ یک سورپرایز برای آواکس های دشمن" [Iran's S-200; A surprise for enemy AWACS] (in Persian). Mashregh News. 19 February 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ "«صیاد 2» زنجیره شکارچیان ایرانی را کامل کرد +عکس" (in Persian). Mashregh News. 8 June 2014. Archived from the original on 26 August 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ "آشنایی با 3 سامانه پدافندی که ایران به جای اس 300 رونمایی کرد +عکس" (in Persian). Mashregh News. 17 November 2014. Archived from the original on 20 November 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ "Iran upgrades S-200 long-range air defence system". 10 July 2013. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Система ПВО "Фаворит" - Средства управления 83М6Е2" [Air defense system "Favorite" - Command post 83M6E2] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Средства управления зенитными комплексами С-300 83М6Е" [Command post for S-300 system 83M6E]. Капустин Яр (in Russian). Archived from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "ЗРС С-400 "Триумф": Обнаружение - дальнее, сопровождение - точное, пуск - поражающий" (in Russian). 3 June 2008. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Система С-200" [S-200 system]. Военное дело (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Автоматизированная система управления Группировка ПВО 73Н6 'Байкал-1'" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "S-200 SA-5 GAMMON". Federation of American Scientists. 3 July 1998. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ↑ Kraus 2019, p. 51.

- 1 2 Kraus 2019, p. 52.

- ↑ Kraus 2019, p. 54.

- ↑ Kraus 2019, p. 45.

- ↑ Kraus 2019, p. 47.

- 1 2 "S-200 (SA-5 Gammon)". Missile Threat. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ "Marschtriebwerk 5D67" (in German). University of Ulm. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- 1 2 "Flugkörper des Komplexes S-200" (in German). University of Ulm. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ↑ Wines, Michael (14 October 2001). "After 9 Days, Ukraine Says Its Missile Hit A Russian Jet". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ↑ "Frontline report: Ukraine employs modified S-200 missiles to attack rear Russian targets". Euromaidan Press. 10 July 2023.

- 1 2 Axe, David (10 July 2023). "Ukraine's Newest Deep-Strike Missile Is An Ex-Soviet Antique—With a Few Tweaks". Forbes. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ↑ Radford, Antoinette; Baker, Graeme (12 August 2023). "Ukraine war: Crimea bridge targeted by missiles, Russia says". BBC News.

- ↑ Chang, Edward (5 December 2017). "'Smoke 'Em'". War Is Boring.

- ↑ "Excerpts From News Sessions on Clash With Libya's Forces". The New York Times. Associated Press. 25 March 1986. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ "Покорение "Ангары"" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ "Зенитная Ракетная Система С-200 Боевое Применение" [S-200 Anti-Aircraft Missile System]. pvo.guns.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ "U.S. Tells Soviet of Concern Over New Missiles for Syria". The New York Times. 8 January 1983. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ "Soviet Is Said to Deploy New Missiles in Syria". The New York Times. Reuters. 18 January 1983. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ Friedman, Thomas L. (21 March 1983). "Syrian Army Said to Be Stronger Than Ever, Thanks to Soviet". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ National Intelligence Daily (PDF) (Report). Central Intelligence Agency. 2 April 1984. p. 5.

- ↑ "Civil War in Syria (8): The Fall of Military Bases". 16 November 2012. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "Syrian rebels say capture air defense base near Damascus". Reuters. 5 October 2012. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ Fadel, Leith (2 January 2017). "Syrian Army captures Air Defense Base in East Ghouta". Al-Masdar News. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ Binnie, Jeremy (17 November 2016). "Syria now operating 'restored' S-200 SAMs". Jane's Defence Weekly. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ "Russia's military presence mounts in Kuweires airport: sources". Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ "Овим руским оружјем је Сирија оборила израелски војни авион" [Syria shot down an Israeli military plane with this Russian weapon]. Правда (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Elwazer, Schams; Hume, Tim; Liebermann, Oren (13 September 2016). "IDF denies Syrian claim to have shot down Israeli warplane, drone". CNN. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ↑ "Израиль нанес авиаудар по целям в Сирии, получив ответ зенитными ракетами". EADaily (in Russian). Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- 1 2 Cenciotti, David (17 March 2017). "Syria claims it shot down an Israeli combat plane; Israel denies: dissecting the latest IAF strike on Damascus". The Aviationist. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Cenciotti, David (18 March 2017). "Israel Bombed Damascus — And Didn't Need Stealth Fighters to Do It". War Is Boring. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ "Israel threatens to 'destroy without hesitation' Syrian air defence systems". Hindustan Times. Agence France-Presse. 19 March 2017. Archived from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Weizman, Steve. "Netanyahu: Syria raids targeted 'advanced' Hezbollah arms". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017 – via Yahoo! News.

- ↑ Zitun, Yoav (16 October 2017). "IAF retaliates against Syrian surface-to-air missile battery". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "חיל האוויר השמיד בסוריה סוללה ששיגרה טיל לעבר מטוסים". ynet. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "צה"ל תקף סוללת נ"מ של צבא סוריה". mako (in Hebrew). 16 October 2017. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- 1 2 "Critically wounded pilot downed in Syria strike walks out of hospital". The Times of Israel. 18 February 2018. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018.

- ↑ Zitun, Yoav (25 February 2018). "Investigation finds pilots of downed F-16 failed to defend themselves". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ↑ Ensor, Josie (10 February 2018). "Israel strikes Iranian targets in Syria after F-16 fighter jet shot down". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ↑ "Pilot of downed F-16 jet regains consciousness, taken off respirator". The Times of Israel. 11 February 2018. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018.

- ↑ Baruch, Uzi; Finkler, Kobi (10 May 2018). "IDF attacks dozens of Iranian targets in Syria". Israel National News.

- ↑ "Russian aircrew deaths: Putin and Netanyahu defuse tension". BBC News. 18 September 2018. Archived from the original on 19 September 2018.

- ↑ Gross, Judah Ari (21 September 2018). "Israel: Russia accepts our take on Syrian downing of plane, coordination goes on". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 13 November 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ "Syria fired missiles for 40 minutes after Israeli strike, hitting Russian plane". The Times of Israel. 21 September 2018. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ "Putin says Israel did not shoot down Russian plane, calls it a tragic accident". The Times of Israel. 18 September 2018.

- ↑ "Missile that hit Northern Cyprus Russian-made S-200 fired from Syria, foreign minister says". Daily Sabah. 1 July 2019. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019.

- ↑ Gross, Judah Ari (22 April 2021). "'Errant Syrian missile' fired at Israeli jet explodes near Dimona nuclear site". The Times of Israel.

- ↑ Newdick, Thomas (22 April 2021). "Syrian Surface-To-Air Missile Flew Way Off Course Triggering Alarms Before Exploding Over Israel". The Drive.

- ↑ Ahronheim, Anna; Joffre, Tzvi (21 August 2021). "Israel accused of striking Syrian site, air defenses kill 4 civilians". The Jerusalem Post.

- ↑ GDC (4 September 2021). "Israeli F-16I Destroyed Russian-made S-200 SAM In Syria". Global Defense Corp. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ↑ Nikolov, Boyko (4 July 2023). "Bulgaria could have sent S-300 and S-200 to Ukraine for $200M". BulgarianMilitary.com. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ↑ IISS 2023, p. 78.

- ↑ "Анализ состояния ПВО и ВВС Ирана" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Iran upgrades S-200 long-range air defence system". AirforceTechnology. 10 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ↑ IISS 2023, p. 327.

- ↑ IISS 2023, pp. 179–180.

- ↑ IISS 2023, p. 264.

- ↑ Lubiejewski, Sylwester (29 May 2023). "Conclusions from the use of aviation in the first half of the first year of the Ukrainian-Russian war" (PDF). Security and Defence Quarterly. 42 (2): 90. doi:10.35467/sdq/161959. eISSN 2544-994X. ISSN 2300-8741. S2CID 258972927.

- ↑ Zięć, Krystian; Smura, Tomasz; Oleksiejuk, Michał; Ciastoń, Rafał; Czulda, Robert (2022). Polskie Siły Powietrzne w operacjach XXI wieku (PDF) (Report) (in Polish). Warsaw: Casimir Pulaski Foundation. ISBN 9788361663195. OCLC 1338055287. Retrieved 18 July 2023.

- ↑ IISS 2023, p. 122.

- ↑ Górski, Maciej (23 October 2014). "Rakiety systemu S-200 i ich służba w Wojsku Polskim". konflikty.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ↑ IISS 2023, pp. 356.

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies (2014). The Military Balance 2014 (Report). Routledge. p. 346. ISSN 0459-7222.

- ↑ IISS 2023, p. 200.

- ↑ "Україна остаточно відмовилася від ЗРК С-200" [Ukraine finally abandoned the S-200 air defense system]. Український мілітарний портал (in Ukrainian). 11 November 2013. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ↑ Newdick, Thomas (10 July 2023). "Is Ukraine Using Old S-200 SAMs In The Land-Attack Role?". The Drive. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ↑ IISS 2023, pp. 315–317.

- ↑ Kraus 2019, pp. 18–20, 28–30.

- 1 2 Kraus 2019, pp. 12–13, 27.

- ↑ Kraus 2019, p. 27.

- ↑ Deb, Sheershoo (23 August 2020). "Full List of India's Air Defence System-Shield of India". DefenceXP. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ↑ "World Missile Directory". Flight International. 2 February 1985. p. 62. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012.

- ↑ IISS 2023, pp. 275–277.

- ↑ IISS 2023, pp. 205–206.

Sources

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (2010). Hackett, James (ed.). The Military Balance 2010 (Report). Routledge. ISSN 0459-7222.

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (2023). Hackett, James (ed.). The Military Balance 2023 (Report). Routledge. ISBN 9781032508955. ISSN 0459-7222.

- Kraus, Peter (2019). Luftverteidigung der DDR: Fla-Ra-Komplex S-200 »Wega« (in German). Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 9783613042124. OCLC 1112139017.