Saint Isaac of Armenia | |

|---|---|

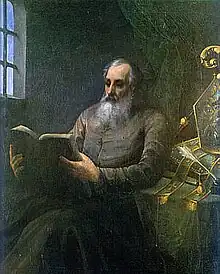

Portrait by Stepanos Nersissian | |

| Catholicos of All Armenians | |

| Born | c. 354 |

| Died | c. 439–441 |

| Venerated in | Oriental Orthodoxy Eastern Orthodoxy Roman Catholicism |

| Feast | 9 September (Roman Catholic Church) [1] Saturday preceding the penultimate Sunday before Lent (Armenian Apostolic Church) 20 November |

Isaac or Sahak of Armenia (354–439) was Catholicos (or Patriarch) of the Armenian Apostolic Church. He is sometimes known as "Isaac the Great," and as "Sahak the Parthian" (Armenian: Սահակ Պարթեւ, Sahak Parthew", Parthian: Sahak-i Parthaw) owing to his fathers Parthian origin, while his mother was an Armenian princess of the Mamikonian family.

Family

Isaac was son of the Christian St. Nerses I and a Mamikonian princess called Sanducht. Through his father he was a Gregorid and was descended from the family of St. Gregory I the Enlightener. He was the fifth Catholicos of the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia after St. Gregory I the Enlightener (301–325), St. Aristaces I (325–333), St. Vrtanes I (333–341) and St. Husik I (341–347). His paternal grandmother was the Arsacid Princess Bambish, the sister of King Tigranes VII (Tiran)[2] and a daughter of King Khosrov III.

Life

Left an orphan at a very early age, Isaac received an excellent literary education in Constantinople, particularly in the Eastern languages. There he married an unnamed woman by whom he had a daughter called Sahakanoush who later married Hamazasp Mamikonian, a wealthy and influential Armenian nobleman. After the death of his wife, he took up a life of seclusion and prayer.[3]

After his election as patriarch in 386, he devoted himself to the religious and scientific training of his people. In 395, while re-building Saint Hripsime Church which had been destroyed by Shapur II, he found an urn containing her relics.[3]

Armenia was then passing through a grave crisis. In 387 it had lost its independence and been divided between the Byzantine Empire and Persia; each division had at its head an Armenian but feudatory king. In the Byzantine territory, however, the Armenians were forbidden the use of the Syriac language, until then exclusively used in divine worship: for this the Greek language was to be substituted, and the country gradually Hellenized; in the Persian districts, on the contrary, Greek was absolutely prohibited, while Syriac was greatly favoured. In this way the ancient culture of the Armenians was in danger of disappearing and national unity was seriously compromised.[4]

To save both Isaac encouraged Mesrop to invent the Armenian alphabet and began to translate the Christian Bible;[5] their translation from the Syriac Peshitta was revised by means of the Septuagint, and even, it seems, from the Hebrew text (between 410 and 430).[3] The liturgy also, hitherto Syrian was translated into Armenian, drawing at the same time on the liturgy of Saint Basil of Caesarea, so as to obtain for the new service a national color. Isaac had already established schools for higher education with the aid of disciples whom he had sent to study at Edessa, Melitene, Constantinople, and elsewhere. Through them he now had the principal masterpieces of Greek and Syrian Christian literature translated, e.g. the writings of Athanasius of Alexandria, Cyril of Jerusalem, Basil, the two Gregorys (Gregory of Nazianzus and Gregory of Nyssa), John Chrysostom, Ephrem the Syrian, etc. Armenian literature in its golden age was, therefore, mainly a borrowed literature.[4]

Through Isaac's efforts the churches and monasteries destroyed by the Persians were rebuilt, education was cared for in a generous way, Zoroastrianism which Shah Yazdegerd I tried to set up was cast out, and three councils held to re-establish ecclesiastical discipline. Isaac is said to have been the author of liturgical hymns.[4]

Two letters, written by Isaac to Theodosius II and to Archbishop Atticus of Constantinople, have been preserved. A third letter addressed to Saint Proclus of Constantinople was not written by him, but dates from the tenth century. Neither did he have any share, as was wrongly ascribed to him, in the First Council of Ephesus of 431, though, in consequence of disputes which arose in Armenia between the followers of Nestorius and the disciples of Acathius of Melitene and Rabbula, Isaac and his church did appeal to Constantinople and through Saint Proclus obtained the desired explanations.

A man of enlightened piety and of very austere life, Isaac owed his deposition by the king in 426 to his great independence of character. In 430, he was allowed to resume his patriarchal throne. In his extreme old age he seems to have withdrawn into solitude, dying at the age of 85 , probably on September 7, 439.[6]

Hovhannes Draskhanakerttsi says his body was taken to Taron and buried in the village of Ashtishat. Several days are consecrated to his memory in the Armenian Apostolic Church.

References

- ↑ "St. Isaac the Great - Saints & Angels".

- ↑ P'awstos Buzandac'i, History of Armenia, p. 81

- 1 2 3 Isavertenc̣, Yakobos. "Armenia and the Armenians" Volume 2, Venice. Armenian Monastery of St. Lazaro, 1875, p. 61 et seq.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 Vailhé, Siméon. "Isaac of Armenia." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 11 November 2021

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "St Isaac the Great", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church 2 ed. ( E. A. Livingstone, ed.) OUP, 2006 ISBN 9780198614425

- ↑ Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "St. Isaac the Great". Encyclopedia Britannica

Sources

- (in French) Les dynasties de la Caucasie chrétienne de l’Antiquité jusqu’au XIXe siècle ; Tables généalogiques et chronologiques, Rome, 1990.

- (in French) Histoire de l'Arménie: des origines à 1071, Paris, 1947.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Isaac of Armenia". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Isaac of Armenia". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.