Hugh of Lincoln | |

|---|---|

St Hugh of Lincoln with his swan Altarpiece showing the saint in the Carthusian habit from the Charterhouse of Saint-Honoré, Thuison, near Abbeville, France (c. 1490-1500) | |

| Bishop of Lincoln | |

| Born | c. 1140[1][2][3] Avalon, Dauphiné, Holy Roman Empire |

| Died | 16 November 1200 (aged 59–60)[4] London, England |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Anglican Communion |

| Canonized | 17 February 1220 by Pope Honorius III |

| Major shrine | St Mary's Cathedral Lincoln, England Parkminster Charterhouse West Sussex |

| Feast | 16 November (Catholic Church) 17 November (Church of England) |

| Attributes | a white swan |

| Patronage | sick children, sick people, shoemakers, swans and Roman Catholic Diocese of Nottingham |

Hugh of Lincoln, O.Cart. (c. 1140[note 1] – 16 November 1200), also known as Hugh of Avalon, was a French-born Benedictine and Carthusian monk, bishop of Lincoln in the Kingdom of England, and Catholic saint. His feast is observed by Catholics on 16 November and by Anglicans on 17 November.

Biography / Vita

Hugh was born at the château of Avalon,[5][2][3] (near the border of the Dauphiné with Savoy) as the son of Guillaume, seigneur of Avalon. His mother, Anne de Theys, died when he was eight, and because his father was a soldier, he went to a boarding-school for his education.[6] Guillaume retired from the world to the Augustinian monastery of Villard-Benoît, near Grenoble, and took his son Hugh, with him.[7][8]

At the age of fifteen, Hugh became a religious novice; he was ordained a deacon at the age of nineteen.[9] About 1159, he was sent as prior to the nearby monastery at Saint-Maximin,[10] presumably already a priest. From that community, he left the Benedictine Order and entered the Carthusian monastery of the Grande Chartreuse,[5] then at the height of its reputation for the rigid austerity of its rules and the earnest piety of its members. There he rose to become procurator of his new Order, in which office he served until he was sent in 1179[11] to become prior of the Witham Charterhouse in Somerset, the first Carthusian house in England.[5]

In 1178 or 1179 King Henry II of England, as part of his penance for the 1170 murder of Thomas Becket, in lieu of going on crusade (as, in his first remorse, he had promised to do), had established a Carthusian charterhouse, which was settled by monks sent from the Grande Chartreuse.[12] There were difficulties in advancing the building works, however, and the first prior was recalled and a second soon died.[13] It was by the special request of the English king that Hugh, whose fame had reached him through one of the nobles of Maurienne, became prior.[7]

Hugh found the monks in dire straits, living in log huts and with no plans yet advanced for the construction of more-permanent monastery buildings. Hugh interceded with the king for royal patronage and at last, probably on 6 January 1182, Henry issued a charter of foundation and endowment for Witham Charterhouse. Hugh's first attention focussed on the building of the Charterhouse. He prepared his plans and submitted them for royal approbation, exacting full compensation from the king for any tenants on the royal estate who would have to be evicted to make room for the building.[7] Hugh presided over the new house till 1186 and attracted many to the community. Among the frequent visitors was King Henry, for the charterhouse lay near the borders of the king's chase in Selwood Forest, a favourite hunting-ground. Hugh admonished Henry for keeping dioceses vacant in order to keep their income for the royal chancellery.

In May 1186, Henry summoned a council of bishops and barons at Eynsham Abbey to deliberate on the state of the Church and on the filling of vacant bishoprics, including Lincoln. On 25 May 1186 the cathedral chapter of Lincoln was ordered to elect a new bishop, and Hugh was elected.[5] Hugh insisted on a second, private election by the canons, securely in their chapterhouse at Lincoln rather than in the king's chapel - the result confirmed his election.

Hugh was consecrated Bishop of Lincoln on 21 September 1186[14] at Westminster.[5] Almost immediately he established his independence of the crown, excommunicating a royal forester and refusing to seat one of Henry's courtly nominees as a prebendary of Lincoln; he softened the king's anger by his diplomatic address and tactful charm. After the excommunications, he came upon the king hunting and was greeted with dour silence. He waited several minutes and the king called for a needle to sew up a leather bandage on his finger. Eventually Hugh said, with gentle mockery, "How much you remind me of your cousins of Falaise" (where William I's unmarried mother Herleva, a tanner's daughter, had come from). At this Henry just burst out laughing and was reconciled. As a bishop, Hugh was exemplary, constantly in residence or travelling within his diocese, generous with his charity, and scrupulous in the appointments he made. He raised the quality of education at the cathedral school. Hugh was also prominent in trying to protect the Jews, great numbers of whom lived in Lincoln, in the persecution they suffered at the beginning of Richard I's reign (1189-1199), and he put down popular violence against them – as later occurred following the 1255 death of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln – in several places.

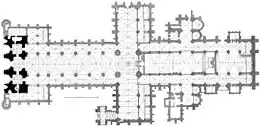

An earthquake had badly damaged Lincoln Cathedral in 1185, and Hugh set about rebuilding and greatly enlarging the structure in the new Gothic style; however, he only lived to see the choir well begun. In 1194, he expanded the St Mary Magdalen's Church, Oxford. Along with Bishop Herbert of Salisbury, Hugh resisted the king's demand for 300 knights for a year's service in his French wars; the entire revenue of both men's offices was then seized by royal agents.[15]

As one of the premier bishops of the Kingdom of England Hugh more than once accepted the role of diplomat to France for King Richard and then for King John in 1199, a trip that ruined his health. He consecrated St Giles' Church, Oxford, in 1200. There is a cross consisting of interlaced circles cut into the western column of the tower that is believed to commemorate this. Also in commemoration of the consecration, St Giles' Fair was established and continues to take place each September to this day.[16] While attending a national council in London, a few months later, Hugh was stricken with an unnamed ailment and died two months later on 16 November 1200.[14][17] He was buried in Lincoln Cathedral.

Bishop Hugh was responsible for the building of the first (wooden) Bishop's Palace at Buckden in Huntingdonshire, halfway between Lincoln and London. Later additions to the Palace were more substantial, and a tall brick tower was added in 1475, protected by walls and a moat, and surrounded by an outer bailey. It was used by the bishops until 1842. The Palace, now known as Buckden Towers, is owned by the Claretians and is used as a retreat and conference centre. A Catholic church, dedicated to Saint Hugh, stands on the site.

Veneration

Hugh was canonised by Pope Honorius III on 17 February 1220,[5] and is the patron saint of sick children, sick people, shoemakers and swans. Hugh is honoured in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival[18] and in the Episcopal Church (USA) on 17 November.

Hugh's Vita, or written life, was composed by his chaplain Adam of Eynsham, a Benedictine monk and his constant associate; it remains in manuscript form in the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

Hugh is the eponym of St Hugh's College, Oxford, where a 1926 statue of the saint stands on the stairs of the Howard Piper Library. In his right hand, he holds an effigy of Lincoln Cathedral, and his left hand rests on the head of a swan.

At Avalon, a round tower in the Romantic Gothic style was built by the Carthusians in 1895 in Hugh's honour on the site of the castle where he was born.[19]

Iconography

Hugh's primary emblem is a white swan, in reference to the story of the swan of Stow, Lincolnshire (site of a palace of the bishops of Lincoln) which had a deep and lasting friendship with the saint, even guarding him while he slept. The swan would follow him about, and was his constant companion while he was at Lincoln. Hugh loved all the animals in the monastery gardens, especially a wild swan that would eat from his hand and follow him about, and yet the swan would attack anyone else who came near Hugh.[6]

Legacy

Both Buckden Towers, and the local Roman Catholic Church in nearby St Neots, are administered by the Claretians.[20] In Lincoln, there is the Roman Catholic St Hugh's Church. There are many parish churches dedicated to St Hugh of Lincoln throughout England including the Church of St Hugh of Lincoln in Letchworth founded by Adrian Fortescue.

A number of churches are dedicated to St Hugh of Lincoln in the United States, including: Episcopal Churches in Elgin, Illinois;[21] and Allyn, Washington;[22] St Hugh of Lincoln Roman Catholic Church, Huntington Station, New York[6] and St Hugh of Lincoln Roman Catholic Church in Milwaukee, Wisconsin,[23] St Hugh Roman Catholic Church and School in Coconut Grove, Miami, Florida.[24]

In 2018 St Hugh was made a subject of the BBC Radio 4 drama The Man who bit Mary Magdalene by Colin Bytheway, starring David Jason as the bishop in search of relics that would help in the construction of Lincoln Cathedral.

References

- 1 2 Woolley, Reginald Maxwell (1927). "Chapter I. Early Days". St. Hugh of Lincoln. London : Society for promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 1. Accessed via Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- 1 2 3 Marson, Charles Latimer (1901). "Chapter I. The Boy Hugh". Hugh, Bishop Of Lincoln: A Short Story Of One Of The Makers of Mediaeval England. London: Edward Arnold. p. 2. Accessed via Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- 1 2 3 Thurston, Herbert (1898). "Book I. Chapter I. The Birth And Early Years of St. Hugh". The Life of Saint Hugh of Lincoln. London : Burns and Oates. p. 2. Accessed via Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ↑ Marson, Charles Latimer (1901). "Chapter X. Homeward Bound". Hugh, Bishop Of Lincoln: A Short Story Of One Of The Makers of Mediaeval England. London: Edward Arnold. p. 154. Accessed via Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 British History Online Bishops of Lincoln Archived 9 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine accessed on 28 October 2007

- 1 2 3 "St. Hugh of Lincoln – Roman Catholic Church". sthugh.org. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- 1 2 3 "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Saint Hugh of Lincoln". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ↑ Thurston, Herbert (1898). "Book I. Chapter I. The Birth And Early Years of St. Hugh". The Life of Saint Hugh of Lincoln. London : Burns and Oates. p. 13. Accessed via Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ↑ Thurston, Herbert (1898). "Book I. Chapter III. Preaching And Parochial Ministry". The Life of Saint Hugh of Lincoln. London : Burns and Oates. p. 23. Accessed via Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ↑ Thurston, Herbert (1898). "Book I. Chapter III. Preaching And Parochial Ministry". The Life of Saint Hugh of Lincoln. London : Burns and Oates. p. 25. Accessed via Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ↑ Woolley, Reginald Maxwell (1927). "Chapter III. The Founding of Witham". St. Hugh of Lincoln. London : Society for promoting Christian Knowledge. p. 25. Accessed via Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 August 2023.

- ↑

Coppack, Glyn; Aston, Michael (2002). Christ's Poor Men: The Carthusians in England. Sutton Series. Tempus. p. 27. ISBN 9780752419619. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

When the first [Carthusian] house in England was established at Witham, it was the Grande Chartreuse that provided the founding party in 1178/9, led by a monk called Narbert.

- ↑

Coppack, Glyn; Aston, Michael (2002). Christ's Poor Men: The Carthusians in England. Sutton Series. Tempus. p. 28. ISBN 9780752419619. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

Narbert could not cope and was recalled to France to be replaced by a new monk, Hamon, who fared little better and died shortly after his arrival from exposure. It was at this time that Henry I began to provide more seriously for the community [...].

- 1 2 Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 255

- ↑ Robinson, J. Armitage. "Peter of Blois" in Somerset Historical Essays, pp. 128 f. Oxford University Press (London), 1921.

- ↑ St Giles' Fair Archived 11 September 2012 at archive.today, St Giles' Church.

- ↑ Thurston, Herbert (1898). "Book IV. Chapter VII. The Death of St. Hugh". The Life of Saint Hugh of Lincoln. London : Burns and Oates. p. 533. Accessed via Internet Archive. Retrieved 10 August 2023.

- ↑ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ↑ La tour d'Avalon accessed on 28 October 2007

- ↑ "RC Parish of St Hugh of Lincoln and St Joseph, Cambridgeshire - Home Page". Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ "St. Hugh Episcopal | Elgin, IL | A Faith Community". St. Hugh Episcopal | Elgin, IL | A Faith Community. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ↑ "St. Hugh". sthughchurch.org. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ↑ "St. Hugh of Lincoln Catholic Church". St. Hugh of Lincoln. Wordpress & DreamHost. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ↑ "St. Hugh Catholic Church & School". sthughmiami.org. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hugh, St". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 857.

Notes

Sources

- British History Online Bishops of Lincoln accessed on 28 October 2007

- King, Richard John Handbook to the Cathedrals of England: Eastern Division (1862) (On-line text).

- La tour d'Avalon accessed on 28 October 2007 – In French

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

External links

- Catholic Saints Info: St. Hugh of Lincoln

- Friends of Buckden Towers

- The RC Parish of St Hugh of Lincoln Buckden and St Joseph in St Neots