Sámuel Nemessányi Hungarian: Nemessányi Sámuel (12 January 1837, in Verbicz-Hušták, Liptószentmiklós, Liptó County – 5 March 1881, Budapest) was a Hungarian luthier, a maker of stringed instruments, such as: violins, violas, and cellos. Nemessányi is considered the most talented and important maker in the Hungarian violin-making school. During his lifetime, he was already acknowledged as the most outstanding craftsmen of stringed instruments in all of Hungary and his instruments are of great importance to Hungarians. His life and work strikingly parallel that of Italian luthier Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù.

Early life

Not much is known about Nemessányi's early life. His middle name of Félix is thought to be wrong, as it does not appear in any known documentation (marriage or birth certificate). It was assumed that he was born in Eperjes (now Prešov, Slovakia), but it is now known that Nemessányi was indeed born in Liptószentmiklós (now Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovakia) to the son of an impoverished shoemaker. His father had urged young Samuel to take up glass blowing, but found that his interest lay in working with wood. At the age of 18, he moved to Pest to learn carpentry and cabinet making.

By a stroke of luck, the workshop where he served his apprenticeship was very close to the violin shop of noted German luthier Johann Baptist Schweitzer. Nemessányi then met Thomas Zach, an assistant to Schweitzer and also a talented maker himself. In April 1855, impressed by Nemessányi's skill with woodworking, Zach took the talented young man as his apprentice and Nemessányi began his training in the most regarded violin shop by the most famous luthiers in Hungary.

Nemessányi's talent developed remarkably under the guidance of his mentors and due to his exceptionally quick progress, he managed to finish the usual 4-year apprenticeship in only 3 years. On May 4, 1858, following the advice of his mentors, he traveled to Prague to meet with Hungarian maker Anton Sitt, a former Schweitzer pupil himself. At Sitt's shop, Nemessányi had the opportunity to examine and repair many fine, old Italian instruments. After spending a year working with Sitt, Nemessányi returned to Hungary a master of his craft at the age of 22.

Middle years

Nemessányi moved to Szeged where he found his first wife. He was married on January 21, 1861 to the 18-year-old Anne Boldizsár. He was well-liked in Szeged and he enjoyed profitable working conditions. Being the restless character that he was, he was soon dissatisfied with the quiet of Szeged. He gathered all his tools and moved his family around from town to town, such as Pécs (Fünfkirchen), working for varied lengths of time in each.

Upon receiving an invitation, Nemessányi uprooted his family once more and moved to Pest, where his reputation as a violin maker was growing. On April 4, 1863, he received his masters diploma from the Pest Musical Instrument Maker's Guild and was accepted as a member. The Nemessányi's moved to 7, Hajó St. (today's Fehér Hajó St.) which was formerly the property of deceased violin maker, Franz Tischenant.

The music scene in Pest was rapidly expanding, thus giving Nemessányi an opportunity to further develop his work. He soon was able to move to a better location at 4, Gránátos St. where he soon became overwhelmed with repairs and orders for new instruments by artists, gypsy violinists, and wealthy amateurs. Nemessányi profited greatly from his work but also received additional support from his father-in-law. Nemessányi was overly generous, usually borrowing money to poor friends which led to a constant lack of it. What few funds remained were spent on his excessive taste for wine, which would eventually become his fatal vice.

In May 1870, Nemessányi's young wife died and his love of adventure and preference for wine suddenly stopped. His four children were taken into custody by their grandparents in Szeged. It was during this period that Nemessányi took on two apprentices: Karl Hermann Voigt and Béla Szepessy. Voigt only stayed with Nemessányi for a year, returning to Vienna soon after. He was replaced by Eduard Bartek, a talented young man. It was not long before Nemessányi took a liking to Bartek's sister, Anna. They were wed in Szeged in 1872 with the support of the Boldizsárs.

Nemessányi returned to his work with a fresh outlook to the newly appointed capital of Budapest. New clients often had to wait for months for their instruments due to his heavy workload. Nemessányi's new wife found his adventurous lifestyle too much to bear and soon left him with their two daughters. To make matters worse, Szepessy also left and travelled to Vienna, Munich, and finally to London where he established himself as a first-rate maker and shop owner. Were it not for Anna Boldizsár's mother, Nemessányi would have remained alone in despair.

She moved to Budapest and brought Nemessányi's four children from his first marriage. They rented a flat at 7 Hatvani St. (today's Kossuth Lajos St.) and she took care of the children and housework. Nemessányi's workshop was once again prospering and in his beautifully furnished drawing room, he hosted the best musicians Budapest had to offer, such as: Ede Reményi, Károly Huber, and his son, the famous prodigy, Jenő Hubay.

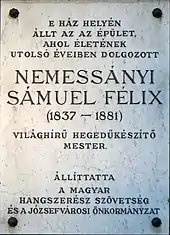

Nemessányi's excessive ways soon began to take over his tranquil life. He wasted the inheritance from his first marriage and his mother-in-law was forced to return to Szeged with the rest of the money and his children, so that they would receive a good education. Nemessányi was once again alone. He left his large flat and moved around to various places in Budapest. Luise Nemessányi, the widow of his brother, became his new partner and she let him stay at 18 Nagyfuvaros St. where she ran a grocery shop. They had two children together. The relationship between Nemessányi and the Boldizsár's was soon restored and even Anna Bartek forgave him for his ways.

Early death

Nemessányi's shaky lifestyle took a great toll on his health. His excessive drinking led to his early demise at the height of his most productive period. On March 5, 1881, he suffered a stroke and collapsed in the street, dying shortly afterward. He was barely 44 years old.

Although none of his sons chose violin making, Nemessányi's apprentices, Béla Szepessy and Eduard Bartek, are generally credited for carrying on the Nemessányi line throughout the late 19th and early 20th century. Bartek taught Paul Pilát who taught many talented apprentices, including: Dezső Bárány, Mihály Reményi, and János Spiegel to name a few.

Despite the fact that Nemessányi was irresponsible, impulsive, and careless, he was a kind and compassionate man whom everyone liked. He was truly a dramatic figure in the world of violin making and left a sizable impression in the Hungarian violin-making school. His life leads a striking parallel with that of Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù who also lived excessively with the drink and died in his early 40s, at the height of his career. Nemessányi's talent with Guarnerian modeling only enhance this fact.

Labels

During his early working years, he wrote his labels by hand. As early as 1863, he began to use printed labels. New labels were ordered in 1871 with larger letters and were mistakenly printed with "Samueli". In some cases he erased the extra 'i', but on some, he left it as it was. On occasion, Nemessányi was known to use the brand mark of "N S". In faked violins, there almost always exists a brand mark, even though Nemessányi barely used it in his own instruments.

His labels appear as such:

Samuel Nemessányi fecit Pestini, 1874

Samuel Nemessányi fecit ad formam Antonio Stradiuarii Pestini 1865

Csinálta Nemessányi Samu Pécsen S.N. 1861 II

Nemessányi Sam P. Maggini után Bpesten 1879

It should be mentioned that it is disputed that Nemessányi ever created a Maggini model.

Samuel Nemessányi fecit ad formam Joseph Guarnerii pestini anno 1879

Instruments

Due to his lifestyle, Nemessányi's work reflected his moods. When he had to deal with unpleasant clients or suffered from depression, he often produced inferior work; however, at his best, he distanced himself from everyone, producing master instruments within a few weeks. These are the instruments that are often compared closely with that of Stradivari and Guarneri.

Nemessányi had a predilection for del Gesù models. He copied some instrument models so perfectly that his unbranded and unlabeled instruments were often in circulation as genuine del Gesù's and other famous Italian makers. Due to this, only a small number of instruments are known to be made by him. Genuine violins and cellos made by Nemessányi himself are outstanding instruments and compare favourably with the best of 18th- and 19th-century instruments. William Henley had this to say about Nemessányi's instruments. "Tonal quality completely congenial to the bravura soloist, neither string dull or unequal, but a splendidly free emission of sonorous strength and brilliancy..."

Nemessányi had a special gift with wood, always using beautifully flamed maple and tight-grained spruce for his instruments. He was often able to work as thin as 2.2 millimetres under the bridge with his best quality spruce. The final shape of each instrument depended on the acoustic qualities of the wood he was working with, resulting in different measurements for nearly every instrument. It is also known that he was an excellent restorer.

Even though Nemessányi's best instruments look nearly identical to their Italian counterparts, it is not this fact alone that created the illusion that some were indeed the genuine articles. It is their playability that also compares favourably with the instruments they were meant to represent. Herbert Goodkind said this about the playability of Nemessányi's instruments: "They possess both mellowness and power, and an ease and evenness of response that enables the performer to produce the gamut of dynamic shadings from pianissimo to fortissimo without loss of quality."

Heinrich W. Ernst once owned a Del Gesù with a label that read "Joseph Guarnerius fecit Cremona 17__". Even though its measurements and appearance match that of a genuine Del Gesù, it was made around 1860 by Samuel Nemessányi. It is illustrated in "Journal of the Violin Society of America" Vol. II, No. 2 by Herbert Goodkind.

As a copyist, Nemessányi is placed in the ranks of the Voller Brothers, Vuillaume, Lupot and John Lott.

Sources

- Original research by László and Mihály Reményi: Original biographical information from an article by László Reményi: VIOLINS AND VIOLINISTS: February, March, and April 1950.

- Benedek, Peter: VIOLIN MAKERS OF HUNGARY: 1997: Heichlinger Druckerei GmbH, Garching.

- Henley, William: UNIVERSAL DICTIONARY OF VIOLIN AND BOW MAKERS in 5 volumes: 1956-60: AMATI PUBLISHING LTD

- Goodkind, Herbert: JOURNAL OF THE VIOLIN SOCIETY OF AMERICA Vol. II, No. 2.