| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

|

Bahira (Arabic: بَحِيرَىٰ, Classical Syriac: ܒܚܝܪܐ) is the name of a Christian monk in Islamic traditions who is said to have foretold Muhammad's prophethood when they met while Muhammad was accompanying his uncle Abu Talib on a trading journey.[1][2] His name derives from the Syriac word bḥīrā, typically used in that language to describe or address a monk, meaning "tested (by God) and approved", and is not a proper name.[3][4]

Etymology of name

The name Bahira comes from the Syriac language, where it is not a proper name but rather a way of addressing or describing a monk. It is an adjective used to denote someone who has been "tested" and "approved," metaphorically meaning "renowned" or "eminent." It takes the form of the passive participle of b-h-r, which translates as "to try, to prove as silver in the fire."[3]

Islamic traditions

The stories of Bahira originate from Islamic traditions, and they exist in various versions with some contradictory elements.[5] The version that other authors of Muhammad’s biographies commonly adopt is the narrative obtained by Ibn Ishaq,[6][7] ostensibly from Abd Allah ibn Abi Bakr al-Ansari,[8] which is essentially, as follows: It is said that in Bosra, a Syrian city, a monk by the name of Bahira learns the descriptions of the prophet to come from a book handed down through generations. He spots a cloud covering Muhammad, a young boy, among a group of traders from Mecca. The cloud follows Muhammad and covers the tree under which he rests. The tree then lowers its branches until Muhammad is under its shadow. Bahira is curious to meet Muhammad and hosts a banquet for them. He questions Muhammad and sees the "sign of prophethood" on his back, which verifies his assumption that Muhammad is the future prophet. He urges Abu Talib, the uncle of Muhammad, to take him back to Mecca without delay, fearing that the Jews might attack him. Abu Talib listens to the advice, and he takes him back to Mecca right away. Shortly after, three "individuals of the scriptures" become aware of Muhammad’s prophethood and try to get to him. However, Bahira intervenes, reminding them of God and that they cannot alter His plan.[9][7]

In another version of the story recorded by al-Tabari, Bahira is more emphatic in his foretelling of Muhammad’s destiny, calling him the apostle of the Lord of the Worlds after witnessing trees and stones bowing down to him. In this version, it is the Byzantines, not the Jews, who Bahira fears will threaten Muhammad’s life. He advises Abu Talib to take Muhammad home as soon as possible, and Abu Talib arranges for Abu Bakr and Bilal ibn Rabah to accompany Muhammad safely to Mecca. Bahira’s foresight soon becomes reality as seven people from the Byzantine Empire show up with the aim of assassinating Muhammad. This version of the story is also documented by al-Tirmidhi and several other biographers of Muhammad.[10]

According to a variation documented by al-Suhayli, possibly derived from al-Zuhri's, it is a Jewish rabbi, not a Christian monk, who meets the young Muhammad on the journey and foretells his future as a prophet. The meeting happens not in Bosra but in Tayma, a city before Syria. As in Ibn Ishaq’s account, the figure advises Abu Talib to take Muhammad back home quickly, fearing that the Jews will murder him if he reaches Syria.[11][12]

To add a spiritual touch to the marriage of Muhammad and Khadija, many of his biographers narrate that he took another trade trip later in his life and met another monk. Some sources call the monk Nastur or Nastura.[13] The narratives generally show this trade trip as being done by Muhammad for Khadija, and he is joined by her slave, named Maysara. The allegedly al-Zuhri's account says that the destination is Hubasha, while Ibn Ishaq’s says that it is Syria.[14] The monk sees Muhammad sitting under a tree that only prophets use, and he asks Maysara if Muhammad has redness in his eyes. Maysara confirms, and the monk concludes that Muhammad is the imminent prophet.[13] In a version by al-Baladhuri and Ibn Habib, the monk’s conclusion about Muhammad’s prophethood results from seeing him create unlimited food.[15] The story continues with the monk buying Muhammad's goods at a high price and two angels covering Muhammad from the blazing sun on their way back. When they return to Medina, Maysara tells Khadija about his experience, which makes her propose marriage to Muhammad.[13] In Ibn Gani's commentary of the Quran, however, it is Abu Bakr who goes with Muhammad on the trip and is told by the monk that the place under the tree where Muhammad sits is only lastly occupied by Jesus.[16]

Analyses

All the stories and the existence of Bahira were dismissed as fabrications by some medieval Muslim hadith critics, one of whom was al-Dhahabi,[17] who argued:

Where was Abu Bakr [during Muhammad's purported journey with Abu Talib]? He was only 10 years old, 2.5 years younger than the Messenger of God. And where was Bilal during this period? Abu Bakr only bought him following the request of the Prophet when the Prophet was 40 years old—Bilal wasn't even born at that point! Moreover, if a cloud had cast its shadow over [Muhammad], how is it possible that the shade of the tree [below it] would move, for the shadow of the cloud would cover the shade of the tree under which he rested? We also observe no instance of the Prophet reminding Abu Talib of the monk's words, nor do Quraysh mention it to him, and none of those elders recount the tale, despite their eager pursuit and request for a story like that. Had the event really occurred, it would have gained immense popularity among them. Moreover, the Prophet would have retained a consciousness of his prophethood and, therefore, would not have harbored doubts about the first occurrence of the revelation to him in the cave of Hira. There would also have been no reason for him to be concerned about his sanity and approach Khadija, nor would he have ascended the mountain peaks to throw himself down. If Abu Talib had been so worried about the Prophet's life that he returned him to Mecca, how could he later have been satisfied to allow him to travel to Syria to trade on Khadija's behalf?[17]

Christian legend

In the wake of the successful Muslim conquest of significant Byzantine and Persian territories, Eastern Christians, who experienced territorial losses, tried to make sense of it biblically. They concluded that it was a transient punishment for their sins, not an indication of divine support for the Muslim cause. From the early 8th century, recognizing the persistence of Muslim rule, responses have evolved, featuring sophisticated defenses of Christianity and counterarguments to Islamic doctrines through disputation literature.[18] This strategy led to the creation of the Christian version of the legend of Bahira during the reign of Caliph al-Ma'mun (813–33). Based on it, two recensions, East Syrian and West Syrian, later developed.[19] Since "Bahira" in Syriac was not a proper name but a way of addressing or describing a monk, "Sergius" was added to the character's name.[20] Later, a reworked recension in Arabic with more references to the Qur'an emerged, followed by a hybrid recension consisting of the Arabic translation of the Syriac legend and the concluding part of the previous Arabic one.[21] Generally, the stories describe the Qur'an as not a book of divine revelation but merely a compilation of Bahira's teachings to Muhammad.[22][4]

Gallery

A young Muhammad being recognized by the monk Bahira. Miniature illustration on vellum from the book Jami' al-Tawarikh (literally "Compendium of Chronicles" but often referred to as The Universal History or History of the World), by Rashid al-Din Hamadani, published in Tabriz, Persia, 1307 A.D. Now in the collection of the Edinburgh University Library, Scotland

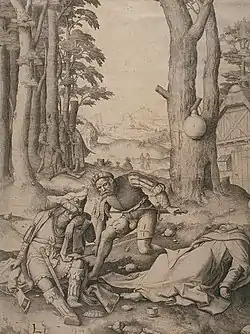

A young Muhammad being recognized by the monk Bahira. Miniature illustration on vellum from the book Jami' al-Tawarikh (literally "Compendium of Chronicles" but often referred to as The Universal History or History of the World), by Rashid al-Din Hamadani, published in Tabriz, Persia, 1307 A.D. Now in the collection of the Edinburgh University Library, Scotland Muhammad and the Monk Sergius, engraving of 1508 by Lucas van Leyden (The soldier takes Muhammad's sword. see text)

Muhammad and the Monk Sergius, engraving of 1508 by Lucas van Leyden (The soldier takes Muhammad's sword. see text)

Bibliography

- Thomas, David; Roggema, Barbara (2009-10-23). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History. Volume 1 (600-900). BRILL. ISBN 978-90-474-4368-1.

- Anthony, Sean W. (2020-04-21). Muhammad and the Empires of Faith: The Making of the Prophet of Islam. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-97452-4.

- Szilágyi, Krisztina (2008). "Muhammad and the Monk: The Making of the Christian Bahira Legend". Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam.

- Maulana Muhammad Ali (2002), The Holy Qur'an: Arabic Text with English Translation and Commentary, New Addition, Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha’ at Islam Lahore Inc., Ohio, USA.

- Osman Kartal (2009), The Prophet’s Scribe Athena Press, London (a novel)

- B. Roggema, The Legend of Sergius Baḥīrā. Eastern Christian Apologetics and Apocalyptic in Response to Islam (The History of Christian-Muslim Relations. Texts and Studies 9; 2008) (includes editions, translations and further references).

- K. Szilágyi, Muhammad and the Monk: The Making of the Christian Baḥīrā Legend, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 34 (2008), in press.

- Abel, A. (1935) “L'Apocalypse de Bahira et la notion islamique du Mahdi” Annuaire de l'Institut de Philologie et d'Histoire Orientale III, 1–12. Alija Ramos, M.

- Roggema, Barbara (2008-08-31). The Legend of Sergius Baḥīrā: Eastern Christian Apologetics and Apocalyptic in Response to Islam. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-474-4195-3.

- Griffith, S. H. (1995). "The legend of the Monk Bahira; the Cult of the Cross and lconoclasm". In P. Canivet; J.-P. Rey (eds.). Muhammad and the Monk Bahîrâ: Reflections on a Syriac and Arabic text from early Abbasid times. Vol. 79. Oriens Christianus. pp. 146–174. ISSN 0340-6407. OCLC 1642167.

- Griffith, S. H. (January 2000). "Disputing with Islam in Syriac: The Case of the Monk of Bêt Hãlê and a Muslim Emir". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 3 (1). Archived from the original on 2006-07-16.

References

- ↑ Abel, A. "Baḥīrā". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second edition. Brill. Brill Online, 2007 [1986].

- ↑ Watt, W. Montgomery (1964). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman, p. 1-2. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 Roggema 2008, p. 57–8.

- 1 2 Roggema, Barbara. "Baḥīrā." Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Edited by: Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Brill Online, 2014 [2011]. Accessed July 12, 2014.

- ↑ Roggema 2008, p. 46.

- ↑ Roggema 2008, p. 38.

- 1 2 Anthony 2020, p. 70.

- ↑ Anthony 2020, p. 71–2.

- ↑ Roggema 2008, p. 38–9.

- ↑ Roggema 2008, p. 39–40.

- ↑ Roggema 2008, p. 44.

- ↑ Anthony 2020, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 Roggema 2008, p. 40.

- ↑ Anthony 2020, p. 71.

- ↑ Roggema 2008, p. 41.

- ↑ Roggema 2008, p. 42.

- 1 2 Anthony 2020, p. 73.

- ↑ Roggema 2008, p. 62.

- ↑ Thomas & Roggema 2009, p. 601–2.

- ↑ Roggema 2008, p. 58.

- ↑ Thomas & Roggema 2009, p. 602.

- ↑ Szilágyi 2008, p. 169.