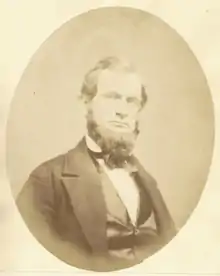

Satterlee Clark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Wisconsin Senate from the 33rd district | |

| In office January 6, 1862 – January 1, 1872 | |

| Preceded by | District established |

| Succeeded by | Lyman Morgan |

| Member of the Wisconsin State Assembly from the Dodge 5th district | |

| In office January 6, 1873 – January 5, 1874 | |

| Preceded by | George Schott |

| Succeeded by | August Heinrich Lehmann |

| Member of the Wisconsin State Assembly from the Marquette district | |

| In office January 1, 1849 – January 7, 1850 | |

| Preceded by | Archibald Nichols |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Spaulding (Marquette & Waushara) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 22, 1816 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Died | September 20, 1881 (aged 65) Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Stroke |

| Resting place | Oakhill Cemetery, Horicon, Wisconsin |

| Spouse | Eliza M. Clark (died 1889) |

| Children |

|

| Relatives |

|

Satterlee Clark (May 22, 1816 – September 20, 1881) was an American attorney, Democratic politician, and Wisconsin pioneer. He served ten years in the Wisconsin State Senate (1862–1872), representing eastern Dodge County, and also served two years in the Wisconsin State Assembly. He wrote a historical essay of his memories of Fort Winnebago and the Black Hawk War in pre-statehood Wisconsin. In his lifetime, he was widely known by the nickname Sat Clark.[1]

Early years

Clark was the eldest son of U.S. Army Major Satterlee Clark of Vermont, an 1807 graduate of the United States Military Academy and a veteran of the War of 1812.[2] Major Clark married Frances Whitcroft, the daughter of a Maryland politician, Burton Whitcroft. Following the War, the elder Clark was assigned to work as a paymaster for the Army in Washington, D.C., where the younger Satterlee Clark was born in 1816. The family moved to Utica, New York, in the 1820s, and at age 10 the younger Clark attended the Utica Free Academy.[2]

Fort Winnebago and the Black Hawk War

In 1828, at age 12, he traveled with his father to Green Bay, then part of the Michigan Territory, where his father was set to operate as sutler for Fort Howard. The next year, in 1829, it was determined that the U.S. Army would set up another fort inland to the south, near the point where the Fox River nearly met the Wisconsin River. The new fort would shortly become known as Fort Winnebago, and soon after its establishment, President Andrew Jackson appointed the 14-year-old Satterlee Clark to serve as sutler for the new outpost. As Clark was too young to accept the role, he contracted with a Detroit merchant, Oliver Newbury, to provide the wares and he worked as the clerk of the goods at Fort Winnebago. According to his own account, he arrived at Fort Winnebago on July 21, 1830.[3][4] He remained there as sutler clerk for most of the remainder of the 1830s and early 1840s, though Henry Merrill was appointed official sutler for the base in 1835.

One of his closest friends during this time was the half-French, half-Winnebago fur trader known as Peter (or Pierre) Pauquette.[3]: 316 Pauquette was well-known throughout the territory as an agent for the American Fur Company, and, through his relationships, Clark learned the languages and became well-acquainted and well-regarded among the Native American tribes of the region.[5]

While working at Fort Winnebago, Clark played a significant role in the Black Hawk War. The war involved a rebellion by a group of aggrieved Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo people, led by a warrior named Black Hawk. In the Spring of 1832, Black Hawk's band crossed into Illinois and was confronted by a group of U.S. Army soldiers and Illinois militia. Black Hawk avoided battle and took his men north into Wisconsin, eventually arriving in the vicinity of Fort Winnebago, which he discovered was now defended by just 30 men. Learning of the danger, the inhabitants of Fort Winnebago selected Satterlee Clark to run to Fort Atkinson to gather reinforcements.[3]: 312–313 Clark, then 16 years old, was selected to make the run due to his familiarity with the land and his good relationships with the Winnebago communities, who gave him shelter as he made the 60 mile trek on foot. General Henry Atkinson, in command at Fort Atkinson, immediately sent 3,000 soldiers to defend Fort Winnebago after receiving the alert from Mr. Clark.[3]: 313 Clark was credited for averting a likely massacre with his swift action.[6]

Clark returned along the same route, and arrived back at Fort Winnebago before the army. With the fort secure, the army sought to pursue Black Hawk's band, which had begun retreating toward the Mississippi River. Clark was one of several young men selected to operate as scouts for the army, along with his friend Peter Pauquette.[3]: 315 He and his companions tracked Black Hawk's band to a crossing on the Wisconsin River, where the Battle of Wisconsin Heights ensued. Following the battle, Clark acknowledges that he and Pauquette each took a scalp from dead Indians and returned to Fort Winnebago.[3]: 315

In the years after the war, Clark was known to be quite sympathetic to the Winnebago.[4] In 1836, Governor Henry Dodge attempted to convince the Winnebago to sell their remaining lands east of the Mississippi River. His effort failed, likely due to the work of Clark and Peter Pauquette convincing many of the Winnebago to refuse the offer.[3]: 318 This resulted in Governor Dodge rescinded Clark's license to trade with the Winnebago.[3]: 318 Pauquette was killed in an altercation with a Winnebago man the day after the treaty was refused.[3]: 318–319

Political career

Through the late 1830s and early 1840s, he served in a number of roles for the Brown County government—Brown County at the time encompassed nearly all of what is now northeast Wisconsin. He also became prominent in the Democratic Party of the Wisconsin Territory and was selected as a delegate to the Democratic Party's Territorial Convention in 1838 which nominated James Duane Doty for delegate to Congress.[7]

Clark studied law while working at Fort Winnebago, and, in 1843 was admitted to the bar. He resigned his sutler duties shortly thereafter and moved to eastern Marquette County (now Green Lake County).[5] There he established an isolated homestead on the prairie near Green Lake, which became known as a haven of hospitality for travelers through the sparsely populated region.[5]

Here, he grew in prominence in the Democratic Party. In the 1848 general election, he was elected as Marquette County's representative to the Wisconsin State Assembly for the 2nd Wisconsin Legislature. During this first term in the Assembly, he was perhaps best known for an anecdote that he climbed the dome of the State Capitol on a sabbath and sang a number of black minstrel songs as people walked to church.[8] He was the Democratic candidate for the 2nd State Senate district in 1849, but was defeated by the Whig candidate George DeGraw Moore. He attempted to regain his Assembly seat in 1850, but lost again, this time to Whig candidate Charles Waldo.[9]

At the time of his death, in 1881, it was noted that Clark had attended every Democratic State Convention from the establishment of the state until his death.[1] At the 1851 Democratic State Convention, he came close to winning the party's nomination for Lieutenant Governor, but ultimately lost out to Timothy Burns.[10] He was, however, chosen as a Democratic presidential elector for the 1852 United States presidential election, and ended up on the winning slate, casting his vote for Franklin Pierce.[5]

In the mid-1850s, Clark relocated to Horicon, Wisconsin, in central Dodge County. He became an increasingly infamous figure in the politics of the state in the bellicose arguments in the run-up to the American Civil War. In 1856 he campaigned to be sent as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention, pledging to cast his vote for Preston Brooks for President—Brooks had, earlier that year, physically attacked abolitionist senator Charles Sumner on the floor of the U.S. Senate.[11] In 1861, following the outbreak of the Civil War, the Democratic Party fell significantly out of favor in Wisconsin, and the papers remarked on Sat Clark as the last party chieftain directing the 1861 State Convention.[12]

Also in 1861, the Wisconsin State Senate expanded from 30 seats to 33, and one of the consequences was the creation of a second Senate district for Dodge County. Clark ran as the Democratic candidate for the 33rd State Senate district, and won election to the 15th Wisconsin Legislature. He would subsequently win re-election four times in this district, serving until 1872. He was then elected to one final term in the Assembly in the 1873 session.

Throughout the Civil War and afterward, Clark was notorious in the state for his stalwart opposition to the war and his defense of Jefferson Davis (who he had known from his years at Fort Winnebago). He considered himself a proud Copperhead.[1] Although his politics were considered extreme, he was personally quite popular and well-liked across the political spectrum. In many of the remembrances of him, it was remarked that his politics were more of a performance. He was known to be a friend of notable Democrats William A. Barstow and Charles H. Larrabee as well as Republicans Alexander Randall and Matthew H. Carpenter. The Wisconsin Historical Society, after his death, recounted how he had charmed Lucy Webb Hayes, the wife of the Republican then-President Rutherford B. Hayes, and earned an invitation to dine with her at the White House.[1]

Later years

After leaving office, Clark was appointed as an officer of the State Agricultural Society, where he served for most of the remainder of his life. He also became employed by the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad Company as a car detective, hired to track down and return cars from the company's train system which had been diverted onto other lines. It was in that capacity he traveled to Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 1881, where he collapsed in the street as he prepared to board a streetcar. He died almost immediately, the cause of death was a stroke.[1]

Personal life and family

Although his father, Major Satterlee Clark, was well-regarded early in his military career, he suffered from alcoholism, which the younger Clark obliquely references in his reminiscences on the vices of the soldiers who operated on the frontier, and the way it shortened their lives.[3] Major Clark was dismissed from service in 1824, and was considered a debtor to the government due to poor bookkeeping as paymaster in Utica. Shortly after his firing, he wrote in the press under the pseudonym "Hancock" making allegations of corruption against the man who had fired him, Secretary of War John C. Calhoun.[13] The allegations resulted in a congressional investigation of Calhoun during his time as Vice President of the United States.[14] Major Clark ultimately received a favorable judgement from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York, restoring some of the pay which had been withheld from him.

Satterlee Clark was one of five children born to Major Clark and Frances Whitcroft. His younger sister, Frances, married Joseph B. Plummer, a Union Army officer who died of wounds during the American Civil War after rising to the rank of brigadier general. His younger brother, Temple Clark, was also a Union Army officer with the 5th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment and rose to the rank of colonel as an adjutant on the staff of General William Rosecrans.[15]

Clark and his wife, Eliza, had at least four children, though one daughter, Charlotte, died in infancy.

Clark's grandfather was Isaac Clark, an American militia officer in the American Revolutionary War who rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Calkins, Colonel Elias A. (1882). "Two Men of Note–William Hull and Satterlee Clark". Report and Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Historical Society. IX: 413–420. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- 1 2 Bagg, Moses M. (1877). The Pioneers of Utica. Utica, New York: Curtiss & Childs. pp. 525–526. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Clark, Satterlee (1879). "Early Times at Fort Winnebago and Black Hawk War Reminiscences". Report and Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Historical Society. VIII: 309–321. Retrieved May 2, 2021.

- 1 2 "Clark, Satterlee [Jr.?] 1816 - 1881". Wisconsin Historical Society. 8 August 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Satterlee Clark". Green Bay Advocate. October 6, 1881. p. 1. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Jones, J. E., ed. (1914). A History of Columbia County, Wisconsin. Vol. I. The Lewis Publishing Company. pp. 69–72. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- ↑ "County meeting". Wisconsin Democrat. August 11, 1838. p. 3. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "A Model Legislator". Janesville Daily Gazette. November 1, 1849. p. 2. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Marquette County". Daily Free Democrat. November 12, 1850. p. 2. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Democratic State Convention". Watertown Chronicle. September 17, 1851. p. 2. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "For the Convention". Wisconsin State Journal. June 3, 1856. p. 2. Retrieved May 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Democratic State Convention". Racine Journal. October 9, 1861. p. 3. Retrieved May 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "The Vice President's Appeal". New York Post. February 17, 1827. p. 1. Retrieved May 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "From the National Intelligencer, Dec. 29". New York Post. January 2, 1827. p. 2. Retrieved May 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Fitch, John (1864). "The Staff". Annals of the Army of the Cumberland. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. pp. 154–155. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ↑ De Bolt, Mary M. (1924). Lineage Book – National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Vol. LXXIV. Washington, D.C.: Press of Judd & Detweiler, Inc. pp. 274. Retrieved May 4, 2021.