Reptile skin is covered with scutes or scales which, along with many other characteristics, distinguish reptiles from animals of other classes. They are made of alpha and beta-keratin and are formed from the epidermis (contrary to fish, in which the scales are formed from the dermis). The scales may be ossified or tubercular, as in the case of lizards, or modified elaborately, as in the case of snakes.[1]

The scales on the top of lizard and snake heads has also been called pileus, after the Latin word for cap, referring to the fact that these scales sit on the skull like a cap.[2]

Lizard scales

Lizard scales vary in form from tubercular to platelike, or imbricate (overlapping). These scales, which on the surface are composed of horny (keratinized) epidermis, may have bony plates underlying them; these plates are called osteoderms.

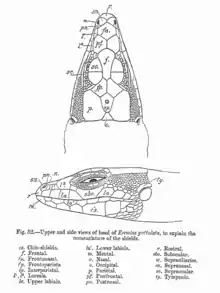

Lizard scales may differ strongly in form on different parts of the lizard and are often of use in taxonomy to differentiate species (or higher taxa, such as families). For instance, members of the family Lacertidae have large head plates (Figure 2) while geckos have no such "plates" but only very small head scales.

While scales are an integral part of reptile taxonomy, the terminology is not entirely consistent. For instance, the scales between the nostrils are sometimes called supranasals[3] and sometimes internasals.

Snake scales

Snakes are entirely covered with scales or scutes of various shapes and sizes. Scales protect the body of the snake, aid it in locomotion, allow moisture to be retained within and give simple or complex colouration patterns which help in camouflage and anti-predator display. In some snakes, scales have been modified over time to serve other functions such as 'eyelash' fringes, and protective covers for the eyes with the most distinctive modification being the rattle of the North American rattlesnakes. Snakes periodically moult their scaly skins and acquire new ones. This permits replacement of old worn out skin, disposal of parasites and is thought to allow the snake to grow. The shape and arrangement of scales is used to identify snake species.

The shape and number of scales on the head, back and belly are characteristic to family, genus and species. Scales have a nomenclature analogous to the position on the body. In "advanced" (Caenophidian) snakes, the broad belly scales and rows of dorsal scales correspond to the vertebrae, allowing scientists to count the vertebrae without dissection.

Scutes

In crocodiles and turtles, the dermal armour is formed from the deeper dermis rather than the epidermis , and does not form the same sort of overlapping structure as snake scales. These dermal scales are more properly called scutes. Similar dermal scutes are found in the feet of birds and tails of some mammals, and are believed to be the primitive form of dermal armour in reptiles.

Ecdysis

The shedding of scales is called ecdysis, or, in normal usage moulting or sloughing.

Moulting performs a number of functions: firstly, the old and worn skin is replaced; secondly, it helps to get rid of parasites such as mites and ticks. Renewal of the skin by moulting is supposed to allow growth in some animals such as insects, however this view has been disputed in the case of snakes.[4][5]

In the case of lizards, this coating is shed periodically and usually comes off in flakes, but some lizards (such as those with elongated bodies) shed the skin in a single piece. Some geckos will eat their own shed skin.

Snakes always shed the complete outer layer of skin in one piece.[1] Snake scales are not discrete but extensions of the epidermis, hence they are not shed separately but are ejected as a complete contiguous outer layer of skin during each moult, akin to a sock being turned inside out.[4] Moulting is repeated periodically throughout a snake's life. Before a moult, the snake stops eating and often hides or moves to a safe place. Just prior to shedding, the skin becomes dull and dry looking and the snake's eyes turn cloudy or blue-coloured. The old layer of skin splits near the mouth and the snake wriggles out, aided by rubbing against rough surfaces. In many cases the cast skin peels backward over the body from head to tail, in one piece like an old sock. A new, larger, and brighter layer of skin has formed underneath.[4][6] An older snake may shed its skin only once or twice a year, but a younger snake that is still growing may shed up to four times a year.[6]

See also

Cited references

- 1 2 Smith, Malcolm A. (1931). The Fauna of British India, Ceylon and Burma. Vol. I.—Loricata, Testudines. London: Secretary of State for India in Council. (Taylor and Francis, printers). xxviii + 185 pp. + Plates I-II. ("Skin", p. 30).

- ↑ Friederich, Ursel (1078). "Der Pileus der Squamata". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde. A (307): 1–64.

- 1 2 3 Boulenger, G.A. (1890). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Reptilia and Batrachia. London: London: Secretary of State for India in Council. (Taylor and Francis, printers).

- 1 2 3 "Are Snakes Slimy?". SZGdocent.org. Singapore Zoological Gardens. Retrieved 14 August 2006.

- ↑ "ZooPax Scales Part 3". WhoZoo.org.

- 1 2 "General Snake Information". Division of Wildlife, South Dakota. Archived from the original on 25 November 2007.

References

- Daniels, J.C. (2002). Book of Indian Reptiles and Amphibians. Mumbai: Bombay Natural History Society/Oxford University Press.

- Smith, Malcolm A. (1935). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Reptilia and Amphibia. Vol. II.—Sauria. London: Secretary of State for India in Council. (Taylor and Francis, printers). xiii + 440 pp. + Plate I + 2 maps.

- Smith, Malcolm A. (1943). The Fauna of British India, Ceylon and Burma, Including the Whole of the Indo-Chinese Sub-region. Reptilia and Amphibia. Vol. III.—Serpentes. London: Secretary of State for India. (Taylor and Francis, printers). xii + 583 pp.