Climate change is having a considerable impact in Malaysia. Increasing temperatures are likely to greatly increase the number of heatwaves occurring annually. Variations in precipitation may increase the frequency of droughts and floods in various local areas. Sea level rise may inundate some coastal areas. These impacts are expected to have numerous environmental and socioeconomic effects, exacerbating existing environmental issues and reinforcing inequality.

Malaysia itself contributes emissions given its significant use of coal and natural gas. However, the use of hydropower has expanded in the 21st century, and other potential energy sources such as solar power and biomass are being explored. The government anticipates the need to adapt in areas such as health and coastal defenses, and has ratified the Paris Agreement. Malaysia has experienced warming and rainfall irregularities particularly in the last two decades[1]

Emissions

As of 2000, the largest sectoral contributor to greenhouse gas emissions was the energy sector, whose 58 million Tonnes (Mt) of CO2 equivalent emissions made up 26% of the national total. This was followed by the transport sector with 36 Mt, or 16%.[2]: 7 Other estimates put the energy sector as producing 55% of CO2 emissions in 2011, and 46% in 2013.[3]

Fossil fuels remain the primary fuel for electricity generation. Demand for electricity grew 64% in the decade prior to 2017. In 2017, over 44% of electricity was produced from burning coal, and 38% from natural gas. The 17% produced through renewable energy came almost completely from hydropower, with other renewables producing just 0.5% of electricity. Coal usage has been increasing, overtaking natural gas usage in 2010. The percentage produced by natural gas has decreased from 57% in 1995, when coal produced only 9%. Most coal is imported, due to the high costs of mining domestic deposits. Much of this change is due to the amount of natural gas being used deliberately being maintained at its 2000 levels, leaving further demand to be taken up by coal as part of diversification. Natural gas production continued to increase, but was diverted to exports. At one point oil was a significant fuel for electricity generation, producing 21% of electricity in 1995, but as oil prices rose this decreased to 2% in 2010 and 0.6% in 2017.[3]

Hydropower is concentrated in East Malaysia, although potential also exists in Perak and Pahang. Despite the recent increase in coal use, no new coal capacity is expected under current plans, which instead target natural gas, and to a lesser extent solar and hydropower. CO2 and CH4 emissions decreased from 2010 to 2017, during a period of hydropower expansion, while the growth in N2O emissions slowed.[3]

Short-lived climate pollutants are related to high levels of air pollution in major cities.[2]: 5

Deforestation, particularly for palm oil and natural rubber production, is also a major contributor to the country's greenhouse gas emissions. A 2016 study estimated deforestation and land use change between 2010 and 2015 contributed to 22.1 million Mg annual CO2 emissions.[4]

Impacts

Existing environmental pressures on natural resources are expected to be exacerbated.[5]: 3 Natural disasters already cause around $1.3 billion in damage annually, mostly due to flooding.[5]: 21

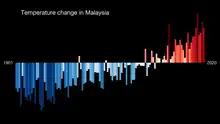

Temperature changes

Temperatures rose by 0.14–0.25 °C per decade from 1970 to 2013.[5]: 6 By 2090, they are projected to rise between an additional 0.8 °C and 3.11 °C depending on global emissions.[5]: 2 There is little expected seasonal variation for temperature increase.[5]: 10 However, heatwaves are expected to increase in frequency and intensity. Currently, a period of three days at the extreme high of expected temperatures has a 2% probability of occurring. Under high emissions scenarios, this will increase to 93%, reflecting the overall higher temperatures.[5]: 12 Such high temperatures will worsen existing urban heat islands such as Kuala Lumpur, which can already reach temperatures 4–6 °C (39–43 °F) higher than surrounding areas.[5]: 20 Annual heat-related deaths among the elderly may go from less than 1 per 100,000 to 45 per 100,000 in high-emission scenarios.[2]: 1 [5]: 23 Coral bleaching is another expected effect, which will have both environmental and economic impacts.[5]: 18

Precipitation and flooding

A reliance on surface water leaves Malaysia vulnerable to precipitation changes, however models do not show significant expected changes, and Kelantan and Pahang may see more water than they do at present.[5]: 15 Rainfall is expected to increase, and more so in East Malaysia than Peninsular Malaysia. The precise magnitude of the increase varies between predictions, and between potential emissions scenarios. Under the scenarios predicting high levels of global emissions, the increase is expected to be around 12% above the current 2,732 millimetres (107.6 in). Flooding, exacerbated by extreme rainfall events, is a present and growing risk.[5]: 2, 6–7, 11 With no action taken, under a high emissions scenario floods may affect an average of 234,500 people annually between 2070 and 2100.[2]: 1 Extreme rainfall events may deposit up to 32% more rain in 2090. In 2010, around 130,000 people in the country were exposed to potential 1-in-25-year flood events. Under high emissions, this will increase to 200,000 by 2030. Even in low emission scenarios, 1-in-100-year events are expected to become 1-in-25-year occurrences.[5]: 13–14 Ecosystem degradation and the spread of urban areas have weakened natural flood resilience.[5]: 16

Sea level rise

From 1993 to 2015, sea levels rose between 3.3 millimetres (0.13 in) and 5 millimetres (0.20 in) annually, depending on location.[5]: 16 In the future, sea levels are expected to rise 0.4–0.7m, with East Malaysia being particularly vulnerable. Coastal agricultural areas are a noted area of risk, and current mangrove habitats may disappear by 2060.[5]: 17 Such a rise will increase the impact of typhoons, which themselves may be increased in intensity.[5]: 14–15 This brings risk to current ecotourism in coastal areas.[5]: 18

Impacts on people

Agriculture is further threatened by droughts and floods. Rice yields may decline by 60%. Other potentially impacted products include rubber, palm oil, and cocoa.[5]: 2 Annual drought probability, which currently lies at 4%, may increase to 9%. Such probability varies by locality, being most likely in Sabah.[5]: 12–13 Overall, precipitation changes will have a more significant impact on agriculture than temperature changes.[5]: 19

Communities most exposed to the impact of climate change are poorer, including those involved in manual labour, agriculture, and fisheries. The impacts of climate change are thus expected to reinforce existing inequality, both in impact and in the ability to adapt.[5]: 22

Mitigation

The International Renewable Energy Agency predicted in 2014 that Malaysia might reach just over 50% of its electricity production from renewables by 2030.[7]

In 2021, the government announced the goal of reaching net zero emissions by 2050 in the Twelfth Malaysia Plan. Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob also said that Malaysia would not build any new coal power plants, would expand electric vehicle infrastructure, and introduce a blue economic blueprint for coastal development.[8]

An attempt to sell 2 million hectares of forest in Sabah as carbon offset credits stalled in 2022 amid local opposition following a lack of consultation and questions as to where profits would go.[9]

Adaptation

Climate resilience measures were included in the Tenth and Eleventh Malaysia Plans.[5]: 3 The government states it has invested in the health service in anticipation of an expected 144% increase in the population at risk of malaria, and expected increases in dengue, diarrhoea, and waterborne diseases.[5]: 23

Adaptation measures such as improving dikes would greatly reduce the impact of sea level rise on coastal communities within this century.[2]: 3

Policies

.jpg.webp)

Malaysia ratified the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1994, and the Kyoto Protocol in 2002. A National Policy on Climate Change was enacted in 2009, along with a National Renewable Energy Policy.[2]: 7 Around this time Malaysia pledged a 40% reduction in carbon intensity by 2020 compared to 2005,[2]: 1 and the Renewable Energy Act was adopted in 2011 alongside the Sustainable Energy Development Authority Act.[2]: 7

In the late 20th century, energy policy centred around diversification for energy security. Renewable energy became more prominent in the 21st century, becoming part of official policy in the 2016–2020 Eleventh Malaysia Plan, alongside the 2016–2025 National Energy Efficiency Action Plan.[3]

Malaysia ratified the Paris Agreement on 16 November 2016, while submitting its first Nationally Determined Contribution. An Intended Nationally Determined Contribution had previously been submitted on 27 November 2015.[5]: 3 [10] The Second National Communication to the UNFCCC emphasises improved Water resource management.[5]: 16

In 2018, the government announced a target for 20% renewable energy by 2025. Hydropower had grown from 5% of the energy mix in 2010 to 17% in 2017, matching much of the increased demand during that time. Solar power has become more used as its price has decreased, such as along the North–South Expressway. There is growing interest in biomass from agricultural waste.[3]

Emission data collected by the Department of Environment is not publicly released.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ Tang, Kuok Ho Daniel (February 2019). "Climate change in Malaysia: Trends, contributors, impacts, mitigation and adaptations". Science of the Total Environment. 650 (Pt 2): 1858–1871. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.650.1858T. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.316. PMID 30290336. S2CID 52923311.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Climate and Health Country Profile – 2015 Malaysia". World Health Organization. 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Siti Norasyiqin Abdul Latif; Meng Soon Chiong; Srithar Rajoo; Asako Takada; Yoon-Young Chun; Kiyotaka Tahara; Yasuyuki Ikegami (15 April 2021). "The Trend and Status of Energy Resources and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in the Malaysia Power Generation Mix". Energies. 14 (8): 2200. doi:10.3390/en14082200.

- ↑ Hamdan, O; Rahman, K Abd; Samsudin, M (June 2016). "Quantifying rate of deforestation and CO2emission in Peninsular Malaysia using Palsar imageries". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 37 (1): 012028. Bibcode:2016E&ES...37a2028H. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/37/1/012028. ISSN 1755-1307. S2CID 132695025.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 World Bank Group; Asian Development Bank (2021). "Climate Risk Country Profile: Malaysia (2021)" (PDF). Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ↑ "Malaysia's 'once in 100 years' flood exposes reality of climate change, better disaster planning needed: Experts". CNA. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ "REmap 2030" (PDF). International Renewable Energy Agency. June 2014. p. 84. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ↑ "12th Malaysia Plan: What you need to know about the 2050 carbon neutral goal and other green measures". CNA. Retrieved 2021-11-19.

- ↑ Cannon, John C. (10 February 2022). "Malaysian officials dampen prospects for giant, secret carbon deal in Sabah". Mongabay. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ↑ "Malaysia's Update of its First Nationally Determined Contribution" (PDF). UNFCCC. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

External links

- "Southeast Asia coal consumption by country, 2010 and 2019". International Energy Agency (IEA).

- "Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2019" (PDF). International Energy Agency (IEA). October 2019.

- "Malaysia Country Summary". World Bank Group Climate Change Knowledge Portal.

- Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (11 May 2020). "Malaysia: CO2 Country Profile". Our World in Data.

- "CO2 Emissions: Malaysia". Climate Trace.

- "The Renewable Energy Roadmap" (PDF). Sustainable Energy Development Authority Malaysia. 28 February 2012.

- "National Energy Efficiency Action Plan". Prime Minister’s Office. 2015.

- "Documents submitted by Malaysia". UNFCCC.