The Marquis of Pombal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Secretary of State of Internal Affairs of the Kingdom | |

| In office 6 May 1756 – 4 March 1777 | |

| Monarch | Joseph I |

| Preceded by | Pedro da Mota e Silva |

| Succeeded by | Viscount of Vila Nova de Cerveira |

| Secretary of State of Foreign Affairs and War | |

| In office 2 August 1750 – 6 May 1756 | |

| Monarch | Joseph I |

| Preceded by | Marco António de Azevedo Coutinho |

| Succeeded by | Luis da Cunha Manuel |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 May 1699 Lisbon, Portugal |

| Died | 8 May 1782 (aged 82) Pombal, Portugal |

| Spouse(s) | Teresa de Noronha e Bourbon Mendonça e Almada Eleonora Ernestina von Daun |

| Occupation | Politician, diplomat |

| Cabinet | |

| Signature | |

Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal and 1st Count of Oeiras (13 May 1699 – 8 May 1782), known as the Marquis of Pombal (Marquês de Pombal; Portuguese pronunciation: [mɐɾˈkeʒ ðɨ põˈbal]), was a Portuguese despotic statesman and diplomat who effectively ruled the Portuguese Empire from 1750 to 1777 as chief minister to King Joseph I. A strong promoter of the absolute power and influenced by the Age of Enlightenment, Pombal led Portugal's recovery from the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and reformed the kingdom's administrative, economic, and ecclesiastical institutions. During his lengthy ministerial career, Pombal accumulated and exercised autocratic power. His cruel persecution of the Portuguese lower classes led him to be known as “Nero of Trafaria”, a village he ordered to be burned with all his inhabitants inside, after refusing to follow his orders.[1]

The son of a country squire and nephew of a prominent cleric, Pombal studied at the University of Coimbra before enlisting in the Portuguese Army, where he reached the rank of corporal. Pombal subsequently returned to academic life in Lisbon, but retired to his family's estates in 1733 after eloping with a nobleman's niece. In 1738, with his uncle's assistance, he secured an appointment as King John V's ambassador to Great Britain. In 1745, he was named ambassador to Austria and served until 1749. When Joseph I acceded to the throne in 1750, Pombal was appointed as Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs.

Despite entrenched opposition from the hereditary Portuguese nobility, Pombal gained Joseph's confidence and, by 1755, was the king's de facto chief minister. Pombal secured his preeminence through his decisive management of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, one of the deadliest earthquakes in history; he maintained public order, organized relief efforts, and supervised the capital's reconstruction in the Pombaline architectural style. Pombal was appointed as Secretary of State for Internal Affairs in 1757 and consolidated his authority during the Távora affair of 1759, which resulted in the execution of leading members of the aristocratic party and allowed Pombal to suppress the Society of Jesus. In 1759, Joseph granted Pombal the title of Count of Oeiras and, in 1769, that of Marquis of Pombal.

A leading estrangeirado strongly influenced by his observations of British commercial and domestic policy, Pombal implemented sweeping commercial reforms, establishing a system of royal monopolistic companies and guilds governing each industry. These efforts included the demarcation of the Douro wine region, created to regulate the production and trade of port wine. In foreign policy, although Pombal desired to decrease Portuguese reliance on Great Britain, he maintained the Anglo-Portuguese Alliance, which successfully defended Portugal from Spanish invasion during the Seven Years' War. Pombal enacted domestic policies that prohibited the import of black slaves into mainland Portugal and Portuguese India,[2] and established the "Companhia Geral de Pernambuco e Paraíba" to strengthened the commerce of african slaves to Brazil, put the Portuguese Inquisition under his control with his brother as chief inquisitor,[3] granted civil rights to the New Christians, and institutionalized Censorship with "Real Mesa Censória". Pombal governed autocratically, curtailing individual liberties, suppressing political opposition, and fostered the black slaves trade to Brazil. [4][5] Following the accession of Queen Maria I in 1777, Pombal was stripped of his offices and ultimately exiled to his estates, where he died in 1782. His legacy was only partially rehabilitated about a century after his death, due to efforts by his descendants, and remains highly controversial.

Early life

Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo (Portuguese pronunciation: [sɨβɐʃtiˈɐ̃w ʒuˈzɛ ðɨ kɐɾˈvaʎu i ˈmɛlu]) was born in Lisbon, the son of Manuel de Carvalho e Ataíde, a country squire with properties in the Leiria region, and of his wife Teresa Luísa de Mendonça e Melo. His uncle, Paulo de Carvalho, was a politically-influential cleric and professor at the University of Coimbra.[6] During his youth Sebastião José studied at the University of Coimbra and then served briefly in the army, reaching the rank of corporal, before returning to academic study.[6] He then moved to Lisbon and eloped with Teresa de Mendonça e Almada (1689–1737), the niece of the Count of Arcos. The marriage was a turbulent one, as she had married him against her family's wishes. Her parents made life unbearable for the young couple; they eventually moved to Melo properties near Pombal. Sebastião José continued his academic pursuits, studying law and history and securing admission in 1734 to a royal historical society.[6]

Sebastião José was fluent in Portuguese and French.[5]

Political career

Prior to his appointment as prime minister in 1755, Pombal had a relatively obscure career.[5][7]

In 1738, with his uncle's assistance,[6] Pombal received his first public appointment as the Portuguese ambassador to Great Britain, where, in 1740, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.[8] Carvalho e Melo used his circulation among influential people to "investigate the causes, techniques, and mechanisms of British commercial and naval power."[9] He did not become fluent in the English language during his time in London.[5]

In 1745, he served as the Portuguese ambassador to Austria.[5] The Queen consort of Portugal, Archduchess Mary Anne Josepha of Austria (1683–1754), was fond of him; after his first wife died she arranged for him to marry the daughter of the Austrian field marshal Leopold Josef, Count von Daun. The King, John V, was not pleased, however, and recalled him in 1749. John V died the following year and his son Joseph I of Portugal was crowned king. Joseph I was fond of Pombal; with the Queen Mother's approval he appointed him as Minister of Foreign Affairs. As the King's confidence in him increased, the King entrusted him with more control of the state.

By 1755, the King appointed him Prime Minister. Impressed by English economic success which he had witnessed as ambassador, Pombal successfully implemented similar economic policies in Portugal.

In February 1761, during the reign of D.José I, Pombal banned the import of black slaves within mainland Portugal and Portuguese India,[10] not for humanitarian reasons, which were contrary to his nature, but because they were necessary labor workforce in Brazil. [11] At the same time, he encouraged the trade in black slaves ("the pieces", in the terms of that time) to that colony, and two companies were founded, with the support and direct involvement of the Marquês de Pombal - the Companhia do Grão-Pará and Maranhão and the Companhia Geral de Pernambuco e Paraíba - whose main activity was precisely the trafficking of slaves, mostly Africans, to brazilian lands. The list of shareholders of the two companies included, in addition to the Marquis, many nobles and clergy. [12][13][11] Between 1757 and 1777, a total of 25,365 black slaves were imported to Pará and Maranhão, coming from West African ports.[14]

He reorganised the army and the navy, and ended the Limpeza de Sangue (cleanliness of blood) civil statutes and their discrimination against New Christians, the Jews that had converted to Christianity, to escape the Portuguese Inquisition, and their descendants regardless of genealogical distance,

Pombaline Reforms

The Pombaline Reforms were a series of reforms intended to make Portugal an economically self-sufficient and commercially strong nation, by means of expanding Brazilian territory, streamlining the administration of colonial Brazil, and fiscal and economic reforms both in the colony and in Portugal.[15][16]

During the Age of Enlightenment Portugal was considered small and unprogressive. It was a country of three million people in 1750. The economy of Portugal before the reforms was a relatively stable one, though it had become dependent on colonial Brazil for much of its economic support, and England for much of its manufacturing support, based on the Methuen Treaty of 1703. Even exports from Portugal went mostly through expatriate merchants like the English port wine shippers and French businessmen like Jácome Ratton, whose memoirs are scathing about the efficiency of his Portuguese counterparts.

The need to grow a manufacturing sector in Portugal was made more imperative by the excessive spending of the Portuguese crown, the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, the expenditures on wars with Spain for South American territories, and the exhaustion of gold mines and diamond mines in Brazil.[17]

His greatest reforms were, however, economic and financial, with the creation of several companies and guilds to regulate every commercial activity. He created the Douro Wine Company which demarcated the Douro wine region for production of Port, to ensure the wine's quality; his was the second attempt to control wine quality and production in Europe, after the Tokaj region of Hungary. He ruled with a heavy hand, imposing strict laws upon all classes of Portuguese society, from the high nobility to the poorest working class, and via his widespread review of the country's tax system. These reforms gained him enemies in the upper classes, especially among the high nobility, who despised him as a social upstart; but also from the common people who saw the centralization and control of the wine production as harmful to their own businnesses. After the Company was established in the city of Porto, several riots began in the city against Pombal's reforms. The rioteers even managed to barge their way inside the Company's headquarters and take the Director of the Company as a hostage. Eventually, the riots were eventually calmed but Pombal's brutality was once more shown when he ordered the main rioteers to be executed and their bodies displayed above Porto's medieval gates. After a few months of not being allowed to take the bodies down, the Bishop of Porto had to oficially inquire the king to allow the bodies to be put to rest.

Further important reforms were carried out in education by Pombal: he expelled the Jesuits in 1759, created the basis for secular public primary and secondary schools, introduced vocational training, created hundreds of new teaching posts, added departments of mathematics and natural sciences to the University of Coimbra, closed University of Evora, and introduced new taxes to pay for these reforms. However, many of these reforms were a complete failure, as the old Jesuits schools were not adequately replaced, and it took over one century to recover the same levels of literacy in Portugal.

Lisbon earthquake

_-_Miguel_%C3%82ngelo_Lupi_(Museu_de_Lisboa%252C_MC.PIN.0702).png.webp)

Disaster fell upon Portugal on the morning of 1 November 1755, when Lisbon was awakened by a violent earthquake with an estimated magnitude of 9 on the Richter scale. The city was razed by the earthquake and ensuing tsunami and fires. Pombal survived by a stroke of luck and, unshaken, immediately took upon the task of rebuilding the city, with his famous quote: What now? We bury the dead and heal the living.[18] Despite the calamity, Lisbon suffered no epidemics and, within less than a year, was already partially rebuilt. This rapid recovery can be attributed to the quick response on the part of the Marquis to enact several "Providences" with the aim of stabilizing the situation and helping the inhabitants of Lisbon.[19]

The new central area of Lisbon was designed by a group of architects specifically to resist subsequent earthquakes, employing a new construction method, "caging", which consisted of a wooden framework erected in the early stages of construction, granting the building a better chance of withstanding an earthquake due to the inherent flexibility of the material. Architectural models were built for tests, with the effects of an earthquake being simulated by marching troops around the models. The buildings and major squares of the Pombaline Downtown of Lisbon are one of its main attractions: they are the world's first earthquake-resistant buildings. Pombal also ordered a pioneering survey that was sent to every parish in the country with several questions, including about the earthquake — the Parochial Memories of 1758.

The questionnaire asked whether dogs or other animals behaved strangely prior to the earthquake, whether there was a noticeable difference in the rise or fall of the water level in wells, and how many buildings had been destroyed and what kind of destruction had occurred. It seems that the results were not properly analysed during the 18th century, in part due to the death of the person in charge, but the answers have allowed modern Portuguese scientists to reconstruct the event with greater precision.

Because the marquis was the first to attempt an objective scientific description of the broad causes and consequences of an earthquake, he is regarded as a forerunner of modern seismological scientists.

Spanish invasion

In 1761 Spain concluded an alliance with France by which Spain would enter the Seven Years' War in an effort to prevent British hegemony. The two countries saw Portugal as Britain's closest ally, due to the Treaty of Windsor. As part of a wider plan to isolate and defeat Britain, Spanish and French envoys were sent to Lisbon to demand that the King and Pombal agree to cease all trade or co-operation with Britain or face war. While Pombal was keen to make Portugal less dependent on Britain, this was a long-term goal, and he and the King rejected the Bourbon ultimatum.

On 5 May 1762, Spain sent troops across the border and penetrated into Trás-os-Montes to capture Porto, but they were repelled by the guerrillas and forced to abandon all their conquests but Chaves, after suffering huge losses (10,000 casualties). Thereby the Spanish general, Nicolás de Carvajal, Marquis of Sarriá, soon lost the Spanish King's confidence, and was replaced by Count of Aranda.

In a second invasion (Province of Lower Beira, July 1762) a combined Franco-Spanish army was initially successful in capturing Almeida and several almost undefended fortresses, but they were soon ground to a halt by a small Anglo-Portuguese force entrenched in the hills East of Abrantes. Pombal had sent urgent messages to London requesting military assistance, consequently 7,104 British troops were sent together with William, Count of Schaumburg-Lippe and military staff to organise the Portuguese Army. Victory in the battles of Valencia de Alcántara and Vila Velha – and above all – a scorched earth tactic coupled with guerrilla actions in the Spanish logistic lines induced starvation and eventually the disintegration of the Franco-Spanish army (15,000 casualties, many of them inflicted by the peasants), whose remnants were driven back and pursued to Spain. The Spanish headquarters in Castelo Branco was taken by a Portuguese force under Townshend, and all the strongholds that had previously been occupied by the Bourbon invaders were retaken, with the exception of Almeida.

A third Spanish offensive in the Alentejo (November 1762) also met defeat in Ouguela, Marvão and Codiceira. The invaders were chased again back into Spain and saw several men captured by the advancing allies. According to a report sent to the British government by British ambassador in Portugal, Edward Hay, the Bourbon armies had suffered 30,000 casualties during their invasion of Portugal.

In the Treaty of Paris, Spain had to restore to Portugal Chaves and Almeida plus all the territory taken from Portugal in South America in 1763 (most of Rio Grande do Sul and Colonia do Sacramento). Only the second was given back, while the vast territory of Rio Grande do Sul (together with present-day Roraima) would be reconquered from Spain in the undeclared Hispano-Portuguese war of 1763–1777. However, Portugal also conquered Spanish territory in South America during the Seven Years' War: most of the Rio Negro Valley (1763) and defeated a Spanish invasion aiming to occupy the right bank of the Guaporé River (in Mato Grosso, 1763) and also in the battle of Santa Bárbara, Rio Grande do Sul (1 January 1763). Portugal was able to keep all these territorial gains.

In the years after the invasion, and despite the crucial British assistance, Pombal began to be increasingly concerned at the rise of British power. Despite being an Anglophile he suspected the British were interested in acquiring Brazil and he was alarmed by the seeming ease by which they had taken Havana and Manila from Spain in 1762. As noted by historian Andreas Leutzsch:

"During Pombal's reign Portugal faced foreign threats, such as the Spanish invasion during the Seven Years' War in 1762. Even if Portugal was able to defeat the Spanish with the help of their British allies, this war of Spain and France against British hegemony made him concerned about Portuguese independence and Portugal's colonies."[20]

— In European National Identities: Elements, Transitions, Conflicts

Opposition to the Jesuits

Having lived outside of Portugal in Vienna and London, the latter city in particular being a major centre of the Enlightenment, Pombal increasingly believed that the Society of Jesus, also known as the "Jesuits", had a grip on science and education,[21] and that they were an inherent drag on an independent, Portuguese-style iluminismo.[22] He was especially familiar with the anti-Jesuit tradition of Britain, and in Vienna he had made friends with Gerhard van Swieten, a confidant of Maria Theresa of Austria and a staunch adversary of the Austrian Jesuits' influence. As prime minister Pombal engaged the Jesuits in a propaganda war, which was watched closely by the rest of Europe, and he launched a number of conspiracy theories regarding the order's desire for power. During the Távora affair (see below) he accused the Society of Jesus of treason and attempted regicide, a major public relations catastrophe for the order, in the age of absolutism.

Historians today emphasise the Society's role in trying to protect Native Americans in the Portuguese and Spanish colonies, and the fact that the limitations placed upon the order resulted in the so-called Guarani War in which the population of the Guarani people was halved by Spanish and Portuguese troops. According to a census conducted in 1756 the population of the Guarani from the seven missions was 14,284, which was about 15,000 less than the population in 1750.[23] The former Jesuit missions were occupied by the Portuguese until 1759.

Pombal named his brother, D. Paulo António de Carvalho e Mendonça, chief inquisitor and used the inquisition against the Jesuits. Pombal was thus an important precursor for the suppression of the Jesuits throughout Europe and its colonies,[24] which culminated in 1773, when European absolutists forced Pope Clement XIV to issue a bull empowering them to suppress the order in their domains.[25]

Expulsion of the Jesuits and consolidation of power

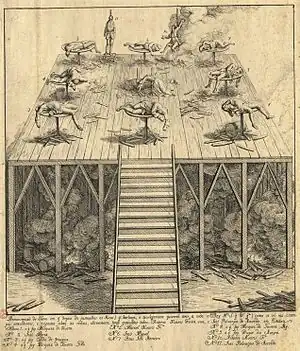

Following the earthquake, Joseph I gave his Prime Minister even more authority, and Pombal became a powerful, progressive dictator. As his power grew, his enemies increased in number, and bitter disputes with the high nobility became frequent. On September 3, 1758, Joseph I was wounded in an attempted assassination when he was returning from a visit to his mistress, the young married Marchioness Teresa de Távora.[26] On December 9, 1758, Pombal formed a special investigatory tribunal (its members were himself and the other secretaries of state).[26] Approximately sixty individuals were convicted when the verdicts of the tribunal were announced January 12, 1759.[26] A number of nobles were sentenced to indefinite imprisonment for their role in the conspiracy.[26] Several nobles, including members of the Távora family and the Duke of Aveiro, were sentenced to execution.[26] They were executed through methods such as the breaking wheel, burning alive, strangling, and beheading.[26] The Duke of Aveiro has generally been regarded as the head of the conspiracy to kill the king.[26] The brutality of the executions stirred controversy in Europe at the time.[26]

On December, 1760, the Marquis, who himself was a "familiar do Santo Oficio" [27](a lay officer of the Inquisition), denounced Father Gabriel Malagrida, a Jesuit, to the Inquisition on charges of heresy.[28][29] He was sentenced to death. On 21 September 1761, the old priest was strangled at the garrote in Rossio Square, then burned on a bonfire and the ashes were thrown into the Tagus river.[30]

After the execution of the Távoras, the persecution of the nobility never stopped. When Pombal left power, around eight hundred political prisoners were released, but in the meantime around two thousand and four hundred had died in prison.[31]

After Pombal had been removed from power by Maria I, an inquiry in the Tavora trial endorsed the guilty verdict of the Duke of Aveiro but exonerated the Tavora family.[32]

There were long-standing tensions between the Portuguese crown and the Jesuits, so that the Távora affair could be considered a pretext for the climax to the conflict that resulted in the Jesuits’ expulsion from Portugal and its empire in 1759. Jesuit assets were confiscated by the crown.[33] According to historians James Lockhart and Stuart Schwartz, the Jesuits' "independence, power, wealth, control of education, and ties to Rome made the Jesuits obvious targets for Pombal's brand of extreme regalism."[33] Pombal showed no mercy, prosecuting every person involved, even women and children. This was the final stroke that broke the power of the aristocracy and ensured the Prime Minister's victory against his enemies. In reward for his swift resolve, Joseph I made his loyal minister Count of Oeiras in 1759. Following the Távora affair, the new Count of Oeiras knew no opposition. Having become the Marquis of Pombal in 1770, he effectively ruled Portugal until Joseph I's death in 1777.

In 1771, botanist Domenico Vandelli published Pombalia, a genus of flowering plants from America, belonging to the family Violaceae and named in honour of the Marquis of Pombal.[34]

Trafaria and Monte Gordo fires and other episodes

In January of 1777, the village of Trafaria was deliberately and completely burned down, with the purpose of capturing rebels who were taking refuge there, with many people dying, either by the fire, or killed by Pina Manique's troops who surrounded the exits .[35]

Pombal ordered the fire of the huts in Monte Gordo aiming to transfer the fishermen to Vila Real de Santo António, where many of those who escaped preferred to later settle in Spain, in Higuerita (Isla Cristina).[36]

In 1757, a popular revolt against the Companhia Geral de Agricultura dos Vinhos do Alto Douro, which had raised the price of wine in the taverns it had a monopoly over, was fiercely repressed by the Marquis. In his own words, "the whole Portuguese nation is horrified by the slightest movement that might appear to be unfaithful to its sovereign". As a result, the city of Porto was occupied by thousands of soldiers, summary trials were carried out and around thirty people were hanged, including several women.[37] The gallows with their corpses were placed in various parts of the city, and later, the heads of the executed were stuck on poles at the entrance to the city.[38]

Decline and death

King Joseph's daughter and successor, Queen Maria I of Portugal, loathed Pombal. She was a devout woman and was influenced by the Jesuits. After acceding to the throne, Maria forced Pombal from office.[39]

She also issued one of history's first restraining orders, commanding that Pombal not be closer than 20 miles to her presence. If she were to travel near his estates, he was compelled to remove himself from his house to fulfill the royal decree. The slightest reference in her hearing to Pombal is said to have induced fits of rage in the Queen.

Pombal's removal was the cause of much rejoicing and disorder in the streets. The Marquis took refuge first in Oeiras and then in his estate near Pombal. The crowd tried to burn down his house in Lisbon, which had to be protected by the troops. Almost all of his former allies abandoned him.[40]

Pombal built a palace in Oeiras, designed by Carlos Mardel. The palace featured formal French gardens enlivened with traditional Portuguese glazed tile walls. There were waterfalls and waterworks set within vineyards.

Pombal died peacefully on his estate at Pombal in 1782. He was a controversial figure in his own era as it is today; today one of Lisbon's busiest squares and the busiest underground station is named Marquês de Pombal in his honour. There is an imposing statue of the Marquis depicting a lion next to him in the square, symbolising the merits of despotic power. This was the first public statue inaugurated by the Military Dictatorship of 1934, based on early projects by one of Pombal's descendants that was mayor of Lisbon. Several intellectuals of the time, such as Almada Negreiros, expressed their dismay and asked this statue to be removed, but it became an important symbol for the Dictatorship and later for the Portuguese Estado Novo.

João Francisco de Saldanha Oliveira e Daun, 1st Duke of Saldanha was his grandson.[41]

See also

References

- ↑ Castelo Branco, Camilo (1882). Perfil do Marquês de Pombal. Porto Editora.

- ↑ Oliveira Ramos, Luís (1971). "Pombal e o esclavagismo" (PDF). Repositório Aberto da Universidade do Porto. pp. 169–170.

- ↑ Freitas, Jordão de (1916). O Marquez de Pombal e o Santo Oficio da Inquisição (Memoria enriquecida com documentos inéditos e facsimiles de assignaturas do benemerito reedificador da cidade de Lisboa) (in Portuguese). Soc. Editora José Bastos. pp. 68, 69.

- ↑ Caldeira, Arlindo Manuel (2013). Escravos e Traficantes no Império Português: O comércio negreiro português no Atlântico durante os séculos XV a XIX (in Portuguese). A Esfera dos Livros. pp. 219–224.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Boxer, C. R. (1977). The Portuguese seaborne empire, 1415-1825. London: Hutchinson. pp. 177–180. ISBN 978-0-09-131071-4. OL 18936702M.

- 1 2 3 4 Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Fausto, Boris; Fausto, Sergio (2014). A Concise History of Brazil. Cambridge University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-107-03620-8.

- ↑ The Royal Society, List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660-2007. See under K-Z: Mello, Sebastian Joseph de Carvalho e, Marquis of Pombal.. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ↑ Maxwell. Naked Tropics: Essays on Empire and Other Rogues. Routledge, 2013. pp. 94-95. ISBN 978-0-415-94577-6.

- ↑ Ramos, Luís O. (1971). "Pombal e o esclavagismo" (PDF). Repositório Aberto da Universidade do Porto.

- 1 2 Caldeira, Arlindo Manuel (2013). Escravos e Traficantes no Império Português: O comércio negreiro português no Atlântico durante os séculos XV a XIX (in Portuguese). A Esfera dos Livros. pp. 219–224.

- ↑ Ramos, Luís O. (1971). "Pombal e o esclavagismo" (PDF). Repositório Aberto da Universidade do Porto.

- ↑ Azevedo, J. Lucio de (1922). O Marquês de Pombal e a sua época (in Portuguese). Annuario do Brasil. p. 332.

- ↑ Boxer (1977), p. 192.

- ↑ Loveman 2004, p. 21.

- ↑ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History: Human capital – Mongolia. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. 2003. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-19-510507-0.

- ↑ Skidmore, Thomas E. Brazil: Five Centuries of Change. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- ↑ Allies, Mary H. "The Voltaire of Portugal," The Catholic World, Vol. XCVI, October 1912/March 1913.

- ↑ Ferreira, Amélia; Esteves, Alexandra Patrícia Lopes (2016). Após a catástrofe: a gestão da emergência e socorro no terramoto de 1755.

- ↑ Leutzsch 2014, p. 188.

- ↑ "The Bismarck of the Eighteenth Century," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. II, 1877.

- ↑ O'Shea, John J. "Portugal, Paraguay and Pombal's Successors," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXXIII, 1908.

- ↑ Jackson, Robert H. (2008). "The Population and Vital Rates of the Jesuit Missions of Paraguay, 1700-1767". The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 38 (3): 401–431. doi:10.1162/jinh.2008.38.3.401. JSTOR 20143650. S2CID 144977776.

- ↑ "Pombal and the Expulsion of the Jesuits from Portugal," The Rambler, Vol. III, 1855.

- ↑ A Matemática em Portugal, de Jorge Buescu, da Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Disney, A. R. (2009). A history of Portugal and the Portuguese empire : from beginnings to 1807. Volume 1, Portugal. Cambridge University Press. pp. 294–297. ISBN 978-0-511-65027-7. OCLC 559058693.

- ↑ Freitas 1916, pp. 10, 106, 122.

- ↑ "Processo do padre Gabriel Malagrida". inquisicao.info (in Portuguese). Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ↑ Azevedo 1922, p. 205.

- ↑ Mostefai, Ourida (2009). "The Condemnation of Fanaticism (by J. Patrick Lee)". Rousseau and l’Infâme. Rodopi. pp. 67–76. ISBN 9789042025059.

- ↑ Saraiva, José Hermano (1986). História concisa de Portugal (10.a edição) (in Portuguese). Publicações Europa-América. pp. 250–251.

- ↑ Disney, A. R. (2009). A history of Portugal and the Portuguese empire : from beginnings to 1807. Volume 1, Portugal. Cambridge University Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-511-65027-7. OCLC 559058693.

- 1 2 Lockhart & Schwartz 1983, p. 391.

- ↑ "Pombalia Vand. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science". Plants of the World Online. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ↑ Branco, Camilo Castelo (1900). Perfil do Marquês de Pombal (in Portuguese). Lopes & Ca. pp. 287–290.

- ↑ Lopes, João Baptista da Silva (1841). Corografia, ou, Memoria económica, estadistica, e topográfica do Reino do Algarve (in Portuguese). Tipografia da Academia Real de Ciências de Lisboa. pp. 382–383.

- ↑ Saraiva (1986), pp. 251–252.

- ↑ Ramos, Rui; Vasconcelos e Sousa, Bernardo; Monteiro, Nuno Gonçalo (2009). "Chap. VII : O tempo de Pombal - O poder do valido e o tempo das providências". História de Portugal. A Esfera dos Livros.

- ↑ Disney, A. R. (2009). A history of Portugal and the Portuguese empire : from beginnings to 1807. Volume 1, Portugal. Cambridge University Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-511-65027-7. OCLC 559058693.

- ↑ Maxwell (1995), pp. 152–153.

- ↑ New International Encyclopedia

Sources

- Alden, Dauril (1968). "Pombal's colonial policy". Royal Government in Colonial Brazil with Special Reference to the Administration of the Marquês of Lavradio, Viceroy, 1769–1779. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520000087.

- Athelstane, John Smith (1843). Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal; with Extracts from his Writings, and from Despatches in the State Paper Office, Never Before Published. Volume 1. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. hdl:2027/nyp.33433082363122. ISBN 978-1402179129.

- Athelstane, John Smith (1843). Memoirs of the Marquis of Pombal; with Extracts from his Writings, and from Despatches in the State Paper Office, Never Before Published. Volume 2. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. hdl:2027/nyp.33433082363130. ISBN 978-1402177675.

- Azevedo, J. Lúcio de (1922). O Marquês de Pombal e a sua Época (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: Anuário do Brasil. ISBN 978-9724739762.

- Branco, Camilo Castelo (1900) - Perfil do Marquês de Pombal (in portuguese)- Lopes & Ca.

- Cheke, Marcus (1938). Dictator of Portugal: A Life of the Marquês of Pombal, 1699–1782. Ayer Company Publishers.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Leutzsch, Andreas (2014). "Portugal: A Future's Past between Land and Sea". In Vogt, Roland; Cristaudo, Wayne; Leutzsch, Andreas (eds.). European National Identities: Elements, Transitions, Conflicts. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1412852685 – via Google Books.

- Lockhart, James; Schwartz, Stuart B. (1983). Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0521299299 – via Internet Archive.

- Loveman, Brian, ed. (2004). "The Iberian military Tradition". For la Patria: Politics and the Armed Forces in Latin America. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-585-28207-7 – via Google Books.

- Maciel, Lizete Shizue Bomura; Neto, Alexandre Shigunov (2006). "Brazilian education in the Pombaline period: a historical analysis of the Pombaline teaching reforms". Educação e Pesquisa. University of São Paulo. 32 (3). doi:10.1590/S1517-97022006000300003. ISSN 1678-4634.

- Maxwell, Kenneth (1995). Pombal, Paradox of the Enlightenment. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521450447 – via Google Books.

- Moore, George (1814). Lives of Cardinal Alberoni, the Duke of Ripperda, and Marquis of Pombal, Three Distinguished Political Adventurers of the Last Century. J. Rodwell. hdl:2027/wu.89094736428. ISBN 978-1270969167.

- Pombal, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, Marquês de. Cartas e outras obras selectas do Marquez de Pombal [selection], 1775–1780.

- Prestage, Edgar. ed. Catholic Encyclopedia, 1911: Marquis de Pombal

- Saraiva, José Hermano (1986). História concisa de Portugal (10.ª edição, in portuguese). Publicações Europa-América

- Skidmore, Thomas E. (1999). Brazil: Five Centuries of Change. Latin American Histories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195058093.

External links

![]() Media related to Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Marquis of Pombal at Wikimedia Commons