Second MacDonald ministry | |

|---|---|

| 1929–1931 | |

| |

| Date formed | 5 June 1929 |

| Date dissolved | 24 August 1931 |

| People and organisations | |

| Monarch | George V |

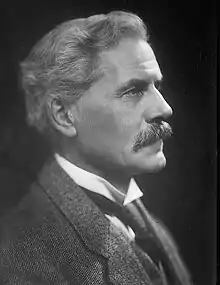

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Prime Minister's history | 1929–1935 |

| Deputy Prime Minister | [note 1] |

| Total no. of members | 86 appointments |

| Member party | Labour Party |

| Status in legislature | 287 / 615 (47%) |

| Opposition party | Conservative Party |

| Opposition leaders |

|

| History | |

| Election(s) | 1929 general election |

| Legislature term(s) | 35th UK Parliament |

| Predecessor | Second Baldwin ministry |

| Successor | First National Government |

The second MacDonald ministry was formed by Ramsay MacDonald on his reappointment as prime minister of the United Kingdom by King George V on 5 June 1929. It was only the second time the Labour Party had formed a government; the first MacDonald ministry held office in 1924.

Background

The government formed lacked a parliamentary majority, its total of 288 seats (arising from 8,300,000 votes) compared to the Conservatives' 255 seats with 8,560,000 votes. Most remaining seats were those of 58 Liberal MPs. The disparity in seats versus votes cast was created by the outcome on boundaries at the time under the first past the post electoral system and the last boundary change under the Representation of the People Act 1918. MacDonald thus had a minority government that needed the support of Lloyd George's MPs to pass legislation. His ministers rapidly faced the problems stemming from the impact of the Great Depression. On the one hand, international bankers insisted that strict budget limits be kept; on the other, trade unions and, particularly, unemployed workers' organisations carried on regular and massive protest actions, including a series of hunger marches.

Policy

The government faced practical enforcement difficulties with its legislation, such as the Coal Mines Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 34), which provided for a 71⁄2-hour daily shift in mines. Owners were guaranteed minimum coal prices through compulsory production quotas among collieries, thus doing away with cut-throat competition. This solution was introduced to prevent a fall in miners' wages.[1] The act introduced a philanthropic cartel replacing the coal merchants' oligopoly to allocate production quotas by control of a central council, while a Mines Reorganisation Commission was established to encourage efficiency through amalgamations. Many mine owners variously offended these provisions due to Labour's lack of enforcement powers.[2]

The Land Utilisation Bill of 1931 would have given ministers sweeping powers to purchase land nationwide (to be run by local authorities and other such bodies). It was mauled by the House of Lords and had no backing from the Treasury so reduced to limited powers to improve agricultural productivity and provide and subsidise smallholdings to the unemployed and agricultural workers, as the Agricultural Land (Utilisation) Act 1931 (21 & 22 Geo. 5. c. 41).[3] Other legislation introduced include the Agricultural Marketing Act 1931 (21 & 22 Geo. 5. c. 42) (which established a board to fix prices for produce),[1] Greenwood's Housing Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 39) (which provided subsidies for slum clearance[4]) and the London Transport Bill 1931 — this was passed by a subsequent Conservative government as the London Passenger Transport Act 1933 (23 & 24 Geo. 5. c. 14). The Housing Act 1930 resulted in the demolition of 245,000 slums by 1939,[5] and the construction of 700,000 new homes.[6] The Housing Act 1930 also allowed local authorities to set up differential rent schemes, with rents related to the incomes of the tenants concerned.[7]

Immediate measures carried out by the government upon taking office included the Unemployment Insurance Act 1929 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 3), which made temporary amendment of the Unemployment Insurance Acts, increasing the state contribution to the fund, the Development (Loan Guarantees and Grants) Act 1929 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 7) authorising grants up to £25 million and a further £25 million in guarantees for public works schemes designed to reduce unemployment, the parallel Colonial Development Act 1929 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 5) authorising grants up to £1 million a year for schemes in the colonies, a measure continuing at the existing levels the subsidies under the Housing Acts, which the Conservatives had threatened to reduce, and a removal of the appointed Guardians whom the Conservatives had put in office in place of the elected Boards in Bedwellty, Chester-le-Street, and Westham.[8] Changes were also made to the taxation system that resulted in the poor paying less tax and the rich paying more.[9]

Expenditure on the insurance fund was raised as a means of ensuring that unemployed persons would not be reduced so quickly to poor relief.[10] The Unemployment Insurance Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 16) increased insurance benefits for certain classes of unemployed who had been on a very low scale, and included a provision that (except in trade disputes) claims for benefits could no longer be disallowed except on the authority of a Court of Referees. Altogether, an estimated 170,000 people were brought into benefit by the combined exchanges in the act. A scheme for training unemployed workers who had little chance of being reabsorbed into their previous occupations was extended, while arrangements were made whereby youths who were helping to support their families out of unemployment pay could live at either the training centres (or lodgings in the vicinity) and have a special remittance of 9 shillings a week made to their homes. In addition, the provision of instruction for unemployed boys and girls between the ages of 14 and 18 was extended.[3]

The Widows', Orphans' and Old Age Contributory Pensions Act 1925 (15 & 16 Geo. 5. c. 70) was amended to cover some hundreds of thousands of additional pensioners, under improved conditions,[8] with the inclusion of widows between the ages of 55 and 70.[4] The Unemployment Insurance Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 16) re-drafted the terms of benefit, so as to remove the major part of the grievance relating to the disqualification of persons alleged to be "not genuinely seeking work", which led to greater numbers of people acquiring unemployment assistance.[11] Other measures carried out in 1929–30 included the Road Traffic Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 43) (which introduced third-party insurance to compensate for property damage and personal injury, made better provisions for road safety,[12] provided greater freedom to municipalities to run omnibus services, the principle of the Fair Wage Clause was applied to all employees on road passenger services, and placed a statutory limit on the working hours of drivers[3]), the Land Drainage Act (which provided some degree of progress in river management[13]), the Public Works Facilities Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 50) (conferring easier borrowing powers), the Workmen's Compensation (Silicosis and Asbestosis) Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 29) (which established disability compensation for asbestos[14]) and the Mental Treatment Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 23).

The 1930 Labour budget provided for largely increased expenditure, contained measures to prevent tax evasion, raised the standard rate of income tax as well as the surtax while making concessions to the smaller taxpayer.[8] A town and country planning act gave local authorities more power to control local and regional planning,[4] while the Housing (Rural Authorities) Act 1931 (21 & 22 Geo. 5. c. 39) provided a sum of £2 million to help the poorer rural districts which were willing but unable to fulfil their housing responsibilities. In addition, an act passed by the previous Conservative government providing assistance towards the improvement of privately owned cottages for land workers was extended for another five years.[3] To protect farm workers from exploitation, additional inspectors were appointed in 1929 to investigate "cases of refusal to pay minimum wages," and as a result of the work carried out by these investigators, wage arrears were recovered for 307 workers with the space of a few months. In addition, levels of support for war veterans and family members were expanded.[15]

In education, various measures were introduced to promote equality and opportunity. More generous standards of school-planning were secured, while special attention was given to the provision of adequate accommodation for practical work. The number of “black-listed” schools was reduced from about 2,000 to about 1,500. From 1929 to 1931, the number of certified teachers in service was increased by about 3,000, while the number of classes with more than 50 children was reduced by about 2,000. Capital expenditure on elementary school building approved by the Board of Education during 1930–1931 stood at over £9 million, more than double the amount approved during 1928–29, the Conservative government's last year in office.[3] In addition, an annual grant to the universities was increased by £250,000.[15] Various military reforms were carried out, with the raising of the minimum age of enrolment into Officers' Training Corps from 13 to 15, the abolition of the death penalty for certain offences, and the modification of the disciplinary code “in the direction of clemency.”[16]

A circular was issued that urged the need for an expansion of provisions for the health and welfare of children under the compulsory school age by the development of nursery schools and other services, and by April 1931, the amount of accommodation available in nursery schools was doubled. The number of staff in the school medical services was increased, while about 3,000 new places were provided in day and residential special schools for crippled or blind children and in open-air schools for delicate children. There was also a large increase in the number of meals supplied to school children, while support given by the government to the National Milk Publicity Council's scheme for supplying milk to children resulted in 600,000 children benefiting daily from this service. Technical education was developed and arrangements were made for co-operation between technical colleges and industry, while new regulations facilitated an expansion of adult education.[3] In addition, the government increased the number of free places that local education authorities could offer to 50%.[17]

To improve safety standards at sea, an international conference was convened by the Labour President of the Board of Trade, which led to 27 governments signing a convention establishing for the first time uniform safety rules for all the cargo ships throughout the world. Conditions for soldiers were improved, while the death penalty for certain offences was abolished. A seven-year limit in connection with war pensions was also removed, while a programme for afforestation was increased.[3]

The Unemployment Insurance Act 1929 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 3) scrapped the "genuinely seeking work" clause in unemployment benefit (which was originally abolished by the first Labour government in 1924, and reintroduced by the Conservatives in 1928), increased dependants' allowances, extended provision for the long-term unemployed, relaxed eligibility conditions, and introduced an individual means test.[2] As a result of the changes made by the government to unemployment provision, the number of people on transitional benefits (payments given to those who had either exhausted their unemployment insurance benefits or did not qualify for them)[18] rose from 120,000 in 1929 to more than 500,000 in 1931.[19]

The National Health Insurance (Prolongation of Insurance) Act 1930 (21 & 22 Geo. 5. c. 5) extended provision of health insurance to unemployed males whose entitlement had run out, while the Poor Prisoners' Defence Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 32) introduced criminal legal aid for appearances in magistrates' courts. The Housing (Scotland) Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 40) and the Housing Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 39) provided local authorities with additional central government subsidies to construct new homes for people who had been moved out of slum clearance areas.[2] The Housing Act 1930 provided for rehousing in advance of demolition, and also for the charging of low rents. The act also made state aid available for the first time for building attractive little houses for older people without families. An obligation was put onto county councils to contribute towards houses built for farm workers, while provisions in the act for improving bad housing and clearing slums were applied to the country districts as well as to urban areas.[3]

A number of measures were also introduced to improve standards of health and safety in the workplace. As a means of improving industrial hygiene, regulations were introduced on 1 June 1931 that prescribed measures of hygiene for establishments engaged in electrolytic chromium plating, while regulations introduced on 28 April 1931 dealt with conditions in the refractory materials industries. On 24 February 1931, special regulations were issued by the Home Office for the prevention of accidents in the shipbuilding industry.[20] The Hairdressers' and Barbers' Shops (Sunday Closing) Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 35) (which came into force in January 1931) provided for the compulsory closing of hairdressers and barbers shops on Sundays and with certain exceptions provided that "no person may carry on the work of a hairdresser on Sunday." An order of February 1930 prescribed protective measures for cement workers, while an order of May 1930 contained provisions concerning the protection of workers in tanneries.[21]

The Local Government Act 1929 (19 & 20 Geo. 5. c. 17) abolished the workhouse test[22] and replaced the Poor Law with public bodies known as public assistance committees for the relief of the poor and destitute, while Poor Law hospitals came under the control of local authorities.[23] The Poor Law Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5. c. 17) also encouraged local authorities (in the words of one study) "to work with a local voluntary group to find suitable employment for deaf people."[24] The lid was kept on the (then) ever present risk of a naval arms race, while the system of naval officer recruitment was reformed to make it less difficult for working-class sailors to secure promotion from the ranks.[25] George Lansbury, the First Commissioner of Works, sponsored a "Brighter Britain" campaign and introduced a number of facilities in London parks such as mixed bathing, boating ponds,[26] and swings and sandpits for children.[27]

A number of other initiatives were undertaken by the Office of Works during Labour's time in office, including extensions in the amenities of the parks and palaces under its charge, and the spending of thousands of pounds on various improvements for the preservation of memorials across the country, as characterised by the restoration of a castle at Porchester near Portsmouth.[16]

In Scotland, various welfare initiatives were carried out by the Scottish Office. Medical services in the Highlands and Islands were extended and stabilised, while limits imposed by a previous Conservative administration on the scale of Poor Law relief were scrapped, along with a system of offering the Poor House "as test for able-bodied men who have been out of work for a long period."[15]

The Second Labour Government's achievements in social policy were, however, overshadowed by the government's failure to tackle the effects of the Great Depression, which left mass unemployment in its wake. Spending on public works was accelerated, although this proved to be inadequate in dealing with the problem. By January 1930, 1.5 million people were out of work, a number which reached almost 2 million by June, and by December it topped 2.5 million.[28] The Lord Privy Seal J. H. Thomas, who was put in charge of the problem of unemployment, was unable to offer a solution,[29] while Margaret Bondfield also failed to come up with an imaginative response.[30] Other members of the cabinet, however, put forward their own proposals for dealing with the Depression.

George Lansbury proposed land reclamation in Great Britain, a colonising scheme in Western Australia, and pensions for people at the age of sixty, while Tom Johnston pushed for national relief schemes such as the construction of a road round Loch Lomond (Johnston was successful in getting a coach road from Aberfoyle to the Trossachs rebuilt). These and similar schemes, however, failed in the Unemployment Committee (a group composed of Thomas and his assistants Johnston, Lansbury, and Oswald Mosley to develop a solution to the unemployment problem), where the four ministers received negative responses to their proposals from the top civil servants from the various government departments.[31]

The one minister whose proposals may have helped Britain to recover quickly from the worst effects of the Great Depression was Oswald Mosley, a former member of the Conservative Party. Frustrated by the government's economic orthodoxy (a controversial policy upheld by the fiscally conservative Chancellor, Philip Snowden), Mosley submitted an ambitious set of proposals for dealing with the crisis to the Labour Cabinet in what became known as "Mosley's Memorandum". These included much greater use of credit to finance development through the public control of banking, rationalisation of industry under public ownership, British agricultural development, import restrictions and bulk purchase agreements with foreign (particularly Imperial) producers, protection of the home market by tariffs, and higher pensions and allowances to encourage earlier retirement from industry and to increase purchasing power.[31] Although MacDonald was sympathetic to some of Mosley's proposals, they were rejected by Snowden and other members of the Cabinet, which led Mosley to resign in frustration in May 1930. The government continued to adhere to an orthodox economic course,[28] as characterised by the controversial decision of the Minister of Labour Margaret Bondfield to push through Parliament an Anomalies Act, aimed at stamping out apparent "abuses" of the unemployment insurance system. This legislation limited the rights of short-time, casual and seasonal workers and of married women to claim unemployment benefit, which further damaged the reputation of the government amongst Labour supporters.[32] Bondfield was caught between the financial orthodoxy of Snowden, the critics of cuts on Labour's backbenches and the baying for even more cuts on the Opposition benches, and in the end she ended up satisfying none of them.[33]

Fate

In the summer of 1931, the government was gripped by a political and financial crisis as the value of the pound and its place on the Gold Standard came under threat over fears that the budget was unbalanced. A run on gold began when a report by the May Committee estimated that there would be a deficit of £120 million by April 1932, and recommended reductions in government expenditure and higher taxes to prevent this.[29]

MacDonald's cabinet met repeatedly to work out the necessary cutbacks and tax rises, while at the same time seeking loans from overseas. It later became clear that the bankers in New York would only provide loans if the government carried out significant austerity measures, such as a 10% reduction in the dole. During August 1931, the Cabinet struggled to produce budget amendments that were politically acceptable but proved unable to do so without causing mass resignations and a full-scale split in the party. The particular issue on which the split occurred was the vote of the cabinet after much discussion to reduce benefit paid to unemployed people under the National Assistance scheme. The Cabinet was unable to reach an agreement on this controversial issue, with nine members opposing the reduction in the dole and eleven supporting it, and on 24 August 1931 the government formally resigned.[29]

The Second Labour Government was succeeded by the First National Ministry, also headed by Ramsay MacDonald and made up of members of Labour, the Conservatives and Liberals, calling itself a National Government. Viewed by many Labour supporters as a traitor, Macdonald was subsequently expelled from the Labour Party, and remained a hated figure within the Labour Party for many years thereafter, despite his great services to his party earlier in his life.[29]

The circumstances surrounding the downfall of the Second Labour Government, together with its replacement by the National Government and its failure to develop a coherent economic strategy for dealing with the effects of the Great Depression, remained controversial amongst historians for many years.

Cabinet

June 1929 – August 1931

- Ramsay MacDonald – Prime Minister and Leader of the House of Commons

- Lord Sankey – Lord Chancellor

- Lord Parmoor – Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords

- J. H. Thomas – Lord Privy Seal

- Philip Snowden – Chancellor of the Exchequer

- J. R. Clynes – Home Secretary

- Arthur Henderson – Foreign Secretary

- Lord Passfield – Secretary of State for the Colonies and Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs

- Thomas Shaw- Secretary of State for War

- William Wedgwood Benn – Secretary of State for India

- Lord Thomson – Secretary of State for Air

- William Adamson – Secretary of State for Scotland

- A. V. Alexander – First Lord of the Admiralty

- William Graham – President of the Board of Trade

- Sir Charles Philips Trevelyan – President of the Board of Education

- Noel Buxton – Minister of Agriculture

- Margaret Bondfield – Minister of Labour

- Arthur Greenwood – Minister of Health

- George Lansbury – First Commissioner of Works

Changes

- June 1930 – J.H. Thomas succeeds Lord Passfield as Dominions Secretary. Passfield remains Colonial Secretary. Vernon Hartshorn succeeds Thomas as Lord Privy Seal. Christopher Addison succeeds Noel Buxton as Minister of Agriculture

- October 1930 – Lord Amulree succeeds Lord Thomson as Secretary of State for Air

- March 1931 – H.B. Lees-Smith succeeds Sir C.P. Trevelyan at the Board of Education. Herbert Morrison enters the cabinet as Minister of Transport. Thomas Johnston succeeds Hartshorn as Lord Privy Seal

List of ministers

Members of the Cabinet are in bold face.

- Notes

- ↑ Retained post during Macdonald's National Government.

- ↑ Entered the Cabinet 19 March 1931.

- ↑ Created Baron Ponsonby of Shulbrede on 17 January 1930.

Notes

- ↑ J. R. Clynes never acquired the title of Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He did however serve as deputy leader of the Labour Party.

References

- 1 2 Hodge, B.; Mellor, W. L. Higher School Certificate History.

- 1 2 3 Harmer, Harry. The Longman Companion to The Labour Party 1900–1998.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The Record of the Second Labour Government. The Labour Party. October 1935.

- 1 2 3 Tanner, Duncan; Thane, Pat; Tiratsoo, Nick. Labour's First Century.

- ↑ "Changing Britain (1760-1900)". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ↑ "Council housing". UK Parliament. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ↑ Scott, Peter. The Making of the Modern British Home: The Suburban Semi and Family Life between the Wars.

- 1 2 3 Cole, G. D. H. A History of the Labour Party from 1914.

- ↑ "Philip Snowden: Biography". Archived from the original on 10 October 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ↑ Derry, T. K.; Jarman, T. L. Modern Britain: Life and Work through Two Centuries of Change.

- ↑ Hopkins, Eric. Industrialisation and society: a social history, 1830–1951.

- ↑ Ellacott, S. E. Wheels on the Road.

- ↑ Hassan, John. A history of water in modern England and Wales.

- ↑ Castleman, Barry I.; Berger, Stephen L. (2005). Asbestos: Medical and Legal Aspects. Aspen Publishers. ISBN 9780735552609.

- 1 2 3 What the Labour Government Has Done. The Labour Party. 1932 – via Florida Atlantic University Digital Library.

- 1 2 Two Years of Labour Rule. The Labour Party. 1931 – via Florida Atlantic University Digital Library.

- ↑ Townsend, Peter; Bosanquet, Nicholas (eds.). Labour and inequality: sixteen Fabian essays.

- ↑ The welfare state: an economic and social history of Great Britain from 1945 to the present day by Pauline Gregg

- ↑ The Coming of the Welfare State by Maurice Bruce

- ↑ The ILO Yearbook 1931 (PDF). International Labour Office.

- ↑ Annual Review 1930 (PDF). International Labour Office.

- ↑ Fraser, Derek. The Evolution of the British Welfare State.

- ↑ Wrigley, Chris. A companion to early twentieth-century Britain.

- ↑ Hampton, Jameel. Disability and the welfare state in Britain. Changes in perception and policy 1948–79.

- ↑ Serving the People: Co-operative Party History from Fred Perry to Gordon Brown.

- ↑ Jones, Stephen G. Sport, Politics and the Working Class: Organized Labour and Sport in Inter-war Britain.

- ↑ Mercer, Derrik (ed.). Chronicle of the Second World War.

- 1 2 Wright, Tony; Carter, Matt. The People's Party: the History of the Labour Party.

- 1 2 3 4 Hopkins, Eric. A Social History of the English Working Classes 1815–1945.

- ↑ Vaizey, John. Social Democracy.

- 1 2 Mowat, Charles Loch. Britain between the wars: 1918–1940.

- ↑ Worley, Matthew. Labour Inside the Gate: A History of the British Labour Party between the Wars.

- ↑ Judge, Tony (2018). Margaret Bondfield: First Woman in the Cabinet.

Further reading

- Butler, David. Twentieth Century British Political Facts 1900–2000

- Carlton, David. MacDonald versus Henderson: The Foreign Policy of the Second Labour Government (2014).

- Heppell, Timothy, and Kevin Theakston, eds. How Labour Governments Fall: From Ramsay Macdonald to Gordon Brown (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

- Howell, David MacDonald's Party. Labour Identities and Crisis, 1922–1931, Oxford: OUP 2002; ISBN 0-19-820304-7

- Marquand, David Ramsay MacDonald, (London: Jonathan Cape 1977); ISBN 0-224-01295-9; the standard scholarly biography; favourable

- Marquand, David. "MacDonald, (James) Ramsay (1866–1937)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2009 accessed 9 Sept 2012; doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34704

- Morgan, Austen: J. Ramsay MacDonald, 1987; ISBN 0-7190-2168-5

- Morgan, Kevin. Ramsay Macdonald (2006)excerpt and text search

- Mowat, C. L. "Ramsay MacDonald and the Labour Party," in Essays in Labour History 1886–1923, edited by Asa Briggs, and john Saville, (1971)

- Mowat, Charles Loch. Britain Between the Wars, 1918–1940 (1955). online

- Owen, Nicholas. "MacDonald's Parties: The Labour Party and the ‘Aristocratic Embrace’ 1922–31," Twentieth Century British History (2007) 18#1 pp 1–53.

- Riddell, Neil. Labour in Crisis: The Second Labour Government, 1929-31 (1999).

- Rosen, Greg (ed.) Dictionary of Labour Biography, London: Politicos Publishing 2001; ISBN 978-1-902301-18-1

- Shepherd, John. The Second Labour Government: A reappraisal (2012).

- Skidelsky, Robert. Politicians and the Slump: The Labour Government of 1929–1931 (1967).

- Taylor, A.J.P. English History: 1914–1945 (1965)

- Williamson, Philip : National Crisis and National Government. British Politics, the Economy and the Empire, 1926–1932, Cambridge: CUP 1992; ISBN 0-521-36137-0

- Wrigley, Chris. "James Ramsay MacDonald 1922–1931," in Leading Labour: From Keir Hardie to Tony Blair, edited by Kevin Jefferys, (1999)

Primary sources

- Barker, Bernard (ed.) Ramsay MacDonald's Political Writings, Allen Lane, London 1972

- Cox, Jane A Singular Marriage: A Labour Love Story in Letters and Diaries (of Ramsay and Margaret MacDonald), London: Harrap 1988; ISBN 978-0-245-54676-1

- MacDonald, Ramsay The Socialist Movement (1911) online

- MacDonald, Ramsay Labour and Peace, Labour Party 1912

- MacDonald, Ramsay Parliament and Revolution, Labour Party 1919

- MacDonald, Ramsay Foreign Policy of the Labour Party, Labour Party 1923

- MacDonald, Ramsay Margaret Ethel MacDonald, 1924

_(2022).svg.png.webp)