Servilia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | |

| Died | |

| Known for | Wife of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Minor, possibly fiancée of Octavian |

| Spouse | Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Minor |

| Parents |

|

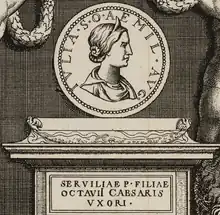

Servilia (sometimes called Servilia Isaurica[1] or Servilia Vatia) was an ancient Roman woman who was the wife of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Minor, the son of the triumvir and Pontifex maximus Lepidus. She may also have been the same Servilia who was at one time engaged to Octavian (the future Emperor Augustus).

Biography

Early life

Servilia was the daughter of Caesarian consul Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus[2] and Junia Prima, the eldest daughter of Servilia Caepionis, a mistress of Julius Caesar and prominent woman of the late republic. This made her the niece of Junia Secunda, Junia Tertia, Marcus Junius Silanus and Marcus Junius Brutus, Caesar's assassin.[3]

Marriage plans

Isaurica was likely the same Servilia who was engaged to Octavian as a young girl, (although it is possible that that girl was actually a sister of hers, as all women who shared fathers had the same name in Republican Rome).[4] This was likely a politically motivated betrothal, since her father was one of Octavian's supporters and her mother, Junia Prima, was a sister-in-law of the triumvir Lepidus (married to Junia Secunda), thus the marriage would have strengthened Octavian's bonds with the two. Nonetheless, he eventually rejected Servilia and married Claudia instead. Servilia's later union with Lepidus was possibly proposed by her mother and the triumvirs in an attempt to soothe any ill feelings created by Octavian's rejection.[5]

Death

In 31 BC, her husband led a plot to assassinate Octavian, motivated by the banishment of his father (and possibly the scorning of his wife). He had tried to restore his exiled father to a position of authority but was caught and condemned to death.[5] When her husband was killed, she committed suicide, the method of which is stated in ancient sources to have been swallowing hot coals[6][7] or alternatively drinking to death, possibly due to coal-eating being regarded as too Gothic.[8] Suicide by a widow was considered a great sign of devotion in Rome at the time.[9] It has been proposed that her manner of death might have been misattributed to her cousin-once-removed Porcia historically.[10]

Research

In the past historians sometimes believed that the Servilia and Augustus had actually married, but it is widely agreed upon today that they were only ever engaged.[11][12]

It has been proposed that the character of Lavinia in The Aeneid was in part intended to represent Servilia.[13]

Cultural depictions

Servilia appears Colleen McCullough's Masters of Rome series, first in The October Horse where Octavian promises her father to marry to get him on his side, when this is decided she is still too young to marry so Octavian plans to wait out the engagement until he can find someone he is actually in love with.[14] In In the 2007 novel Antony and Cleopatra by Australian author Colleen McCullough, Servilia is mentioned several times. She is described as a virgin who Octavian has little interest in and knows she will marry Lepidus instead.[15]

See also

- Women in ancient Rome

- Category:Wives of Augustus

References

- ↑ Adams, Freeman (1955). "The Consular Brothers of Sejanus". The American Journal of Philology. 76 (1): 70–76. doi:10.2307/291707. JSTOR 291707.

- ↑ Galinsky, Karl (2012). Augustus: Introduction to the Life of an Emperor. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780521744423.

- ↑ Corrigan, Kirsty (2015). Brutus: Caesar's Assassin. Pen and Sword. p. 128. ISBN 9781848847767.

- ↑ Treggiari, Susan (2019-01-03). Servilia and her Family. Oxford University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-19-256465-8.

- 1 2 Weigel, Richard D. (2002). Lepidus: The Tarnished Triumvir. Routledge. p. 96. ISBN 9781134901647.

- ↑ Carter, John Mackenzie (1970). The battle of Actium: the rise & triumph of Augustus Caesar. Turning points in History. University of Michigan: Hamilton. p. 228. ISBN 9780241015162.

- ↑ Rollin, Charles (1750). The Roman History, from the Foundation of Rome to the Battle of Actium. Translated from the French. R. Reilly.

- ↑ Baldwin, Barry (1989). Roman and Byzantine Papers. London Studies in Classical Philology. Vol. 21. University of Michigan: Gieben. p. 527. ISBN 9789050630177.

- ↑ Treggiari, Susan (2019-01-03). Servilia and her Family. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-256465-8.

- ↑ Blackwell, Thomas (1795). "Memoirs of the Court of Augustus: Continued and completed from the original papers of the late Thomas Blackwell".

- ↑ (Italy), Rome (1735). "The Lives and Surprising Amours of the Empresses, Consorts to the First Twelve Caesars of Rome ... Taken from the Ancient Greek and Latin Authors. With Historical and Explanatory Notes. [By Jacques Roergas de Serviez. Translated by George James.]".

- ↑ Münzer, Friedrich; m]Nzer, Professor Friedrich (1999). Roman Aristocratic Parties and Families. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801859908.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Virgil Society. Vol. 10. Indiana University. 1970. p. 42.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ McCullough, Colleen (26 November 2002). The October Horse: A Novel of Caesar and Cleopatra. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743214698.

- ↑ McCullough, Colleen (2013-12-03). Antony and Cleopatra. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-6765-9.

Further reading

- L'Hoir, F. Santoro (2018). The Rhetoric of Gender Terms: 'Man', 'Woman', and the Portrayal of Character in Latin Prose. Mnemosyne, Supplements. BRILL. ISBN 9789004329164.