"Sestina"

In fair Provence, the land of lute and rose,

Arnaut, great master of the lore of love,

First wrought sestines to win his lady's heart,

For she was deaf when simpler staves he sang,

And for her sake he broke the bonds of rhyme,

And in this subtler measure hid his woe.

'Harsh be my lines,' cried Arnaut, 'harsh the woe

My lady, that enthorn'd and cruel rose,

Inflicts on him that made her live in rhyme!'

But through the metre spake the voice of Love,

And like a wild-wood nightingale he sang

Who thought in crabbed lays to ease his heart.

First two stanzas of the sestina "Sestina"

Edmund Gosse (1879)

A sestina (Italian: sestina, from sesto, sixth; Old Occitan: cledisat [klediˈzat]; also known as sestine, sextine, sextain) is a fixed verse form consisting of six stanzas of six lines each, normally followed by a three-line envoi. The words that end each line of the first stanza are used as line endings in each of the following stanzas, rotated in a set pattern.

The invention of the form is usually attributed to Arnaut Daniel, a troubadour of 12th-century Provence, and the first sestinas were written in the Occitan language of that region. The form was cultivated by his fellow troubadours, then by other poets across Continental Europe in the subsequent centuries; they contributed to what would become the "standard form" of the sestina. The earliest example of the form in English appeared in 1579, though they were rarely written in Britain until the end of the 19th century. The sestina remains a popular poetic form, and many sestinas continue to be written by contemporary poets.

History

.jpg.webp)

The oldest-known sestina is "Lo ferm voler qu'el cor m'intra", written around 1200 by Arnaut Daniel, a troubadour of Aquitanian origin; he refers to it as "cledisat", meaning, more or less, "interlock".[1] Hence, Daniel is generally considered the form's inventor,[2] though it has been suggested that he may only have innovated an already existing form.[3] Nevertheless, two other original troubadouric sestinas are recognised,[4] the best known being "Eras, pus vey mon benastruc" by Guilhem Peire Cazals de Caortz; there are also two contrafacta built on the same end-words, the best known being Ben gran avoleza intra by Bertran de Born. These early sestinas were written in Old Occitan; the form started spilling into Italian with Dante in the 13th century; by the 15th, it was used in Portuguese by Luís de Camões.[5][6]

The involvement of Dante and Petrarch in establishing the sestina form,[7] together with the contributions of others in the country, account for its classification as an Italian verse form—despite not originating there.[8] The result was that the sestina was re-imported into France from Italy in the 16th century.[9] Pontus de Tyard was the first poet to attempt the form in French, and the only one to do so prior to the 19th century; he introduced a partial rhyme scheme into his sestina.[10]

English

An early version of the sestina in Middle English is the "Hymn to Venus" by Elizabeth Woodville (1437–1492); it is an "elaboration" on the form, found in one single manuscript.[11] It is a six-stanza poem that praises Venus, the goddess of love,[12] and consists of six seven-line stanzas in which the first line of each stanza is also its last line, and the lines of the first stanza provide the first lines for each subsequent stanza.[13]

The first appearance of the sestina in English print is "Ye wastefull woodes", comprising lines 151–89 of the August Æglogue in Edmund Spenser's Shepherd's Calendar, published in 1579. It is in unrhymed iambic pentameter, but the order of end-words in each stanza is non-standard – ending 123456, 612345, etc. – each stanza promoting the previous final end-word to the first line, but otherwise leaving the order intact; the envoi order is (1) 2 / (3) 4 / (5) 6.[14] This scheme was set by the Spaniard Gutierre de Cetina.[15]

Although they appeared in print later, Philip Sidney's three sestinas may have been written earlier, and are often credited as the first in English. The first published (toward the end of Book I of The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia, 1590[16]) is the double sestina "Ye Goatherd Gods". In this variant the standard end-word pattern is repeated for twelve stanzas, ending with a three-line envoi, resulting in a poem of 75 lines. Two others were published in subsequent editions of the Arcadia. The second, "Since wailing is a bud of causeful sorrow", is in the "standard" form. Like "Ye Goatherd Gods" it is written in unrhymed iambic pentameter and uses exclusively feminine endings, reflecting the Italian endecasillabo. The third, "Farewell, O sun, Arcadia's clearest light", is the first rhyming sestina in English: it is in iambic pentameters and follows the standard end-word scheme, but rhymes ABABCC in the first stanza (the rhyme scheme necessarily changes in each subsequent stanza, a consequence of which is that the 6th stanza is in rhyming couplets). Sidney uses the same envoi structure as Spenser. William Drummond of Hawthornden published two sestinas (which he called "sextains") in 1616, which copy the form of Sidney's rhyming sestina. After this, there is an absence of notable sestinas for over 250 years,[17] with John Frederick Nims noting that, "... there is not a single sestina in the three volumes of the Oxford anthologies that cover the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries."[18]

In the 1870s, there was a revival of interest in French forms, led by Andrew Lang, Austin Dobson, Edmund Gosse, W. E. Henley, John Payne, and others.[19] The earliest sestina of this period is Algernon Charles Swinburne's "Sestina".[20] It is in iambic pentameter rhyming ABABAB in the first stanza; each stanza begins by repeating the previous end-words 6 then 1, but the following 4 lines repeat the remaining end-words ad lib; the envoi is (1) 4 / (2) 3 / (5) 6. In the same volume (Poems and Ballads, Second Series, 1878) Swinburne introduces a "double sestina"[5][21] ("The Complaint of Lisa") that is unlike Sidney's: it comprises 12 stanzas of 12 iambic pentameter lines each, the first stanza rhyming ABCABDCEFEDF. Similar to his "Sestina", each stanza first repeats end-words 12 then 1 of the previous stanza; the rest are ad lib. The envoi is (12) 10 / (8) 9 / (7) 4 / (3) 6 / (2) 1 / (11) 5.

From the 1930s, a revival of the form took place across the English-speaking world, led by poets such as W. H. Auden, and the 1950s were described as the "age of the sestina" by James E. B. Breslin.[22] "Sestina: Altaforte" by Ezra Pound and "Paysage moralisé" by W. H. Auden are distinguished modern examples of the sestina.[23][24] The sestina remains a popular closed verse form, and many sestinas continue to be written by contemporary poets;[25] notable examples include "Six Bad Poets" by Christopher Reid,[26][27] "The Guest Ellen at the Supper for Street People" by David Ferry and "IVF" by Kona Macphee.[2][28]

Form

Although the sestina has been subject to many revisions throughout its development, there remain several features that define the form. The sestina is composed of six stanzas of six lines (sixains), followed by a stanza of three lines (a tercet).[5][29] There is no rhyme within the stanzas;[30] instead the sestina is structured through a recurrent pattern of the words that end each line,[5] a technique known as "lexical repetition".[31]

In the original form composed by Daniel, each line is of ten syllables, except the first of each stanza which are of seven.[32] The established form, as developed by Petrarch and Dante, was in hendecasyllables.[7] Since then, changes to the line length have been a relatively common variant,[33] such that Stephanie Burt has written: "sestinas, as the form exists today, [do not] require expertise with inherited meter ...".[34]

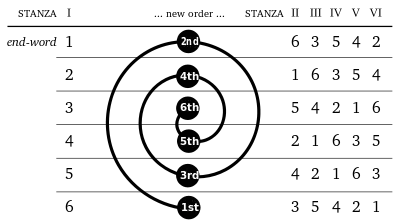

The pattern that the line-ending words follow is often explained if the numbers 1 to 6 are allowed to stand for the end-words of the first stanza. Each successive stanza takes its pattern based upon a bottom-up pairing of the lines of the preceding stanza (i.e., last and first, then second-from-last and second, then third-from-last and third).[5] Given that the pattern for the first stanza is 123456, this produces 615243 in the second stanza, numerical series which corresponds, as Paolo Canettieri has shown, to the way in which the points on the dice are arranged.[35] This genetic hypothesis is supported by the fact that Arnaut Daniel was a strong dice player and various images related to this game are present in his poetic texts.

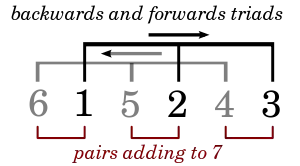

Another way of visualising the pattern of line-ending words for each stanza is by the procedure known as retrogradatio cruciata, which may be rendered as "backward crossing".[36] The second stanza can be seen to have been formed from three sets of pairs (6–1, 5–2, 4–3), or two triads (1–2–3, 4–5–6). The 1–2–3 triad appears in its original order, but the 4–5–6 triad is reversed and superimposed upon it.[37]

The pattern of the line-ending words in a sestina is represented both numerically and alphabetically in the following table:

| Stanza 1 | Stanza 2 | Stanza 3 | Stanza 4 | Stanza 5 | Stanza 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 A | 6 F | 3 C | 5 E | 4 D | 2 B |

| 2 B | 1 A | 6 F | 3 C | 5 E | 4 D |

| 3 C | 5 E | 4 D | 2 B | 1 A | 6 F |

| 4 D | 2 B | 1 A | 6 F | 3 C | 5 E |

| 5 E | 4 D | 2 B | 1 A | 6 F | 3 C |

| 6 F | 3 C | 5 E | 4 D | 2 B | 1 A |

The sixth stanza is followed by a tercet that is known variably by the French term envoi, the Occitan term tornada,[5] or, with reference to its size in relation to the preceding stanzas, a "half-stanza".[7] It consists of three lines that include all six of the line-ending words of the preceding stanzas. This should take the pattern of 2–5, 4–3, 6–1 (numbers relative to the first stanza); the first end-word of each pair can occur anywhere in the line, while the second must end the line.[39] However, the end-word order of the envoi is no longer strictly enforced.[40]

"Sestina"

Time to plant tears (6), says the almanac (5).

The grandmother (2) sings to the marvelous stove (4)

and the child (3) draws another inscrutable house (1).

The envoi to "Sestina"; the repeated words are emboldened and labelled.

Elizabeth Bishop (1965)[41]

The sestina has been subject to some variations, with changes being made to both the size and number of stanzas, and also to individual line length. A "double sestina" is the name given to either: two sets of six six-line stanzas, with a three-line envoy (for a total of 75 lines),[16] or twelve twelve-line stanzas, with a six-line envoy (for a total of 150 lines). Examples of either variation are rare; "Ye Goatherd Gods" by Philip Sidney is a notable example of the former variation, while "The Complaint of Lisa" by Algernon Charles Swinburne is a notable example of the latter variation.[42] In the former variation, the original pattern of line-ending words, i.e. that of the first stanza, recurs in the seventh stanza, and thus the entire change of pattern occurs twice throughout. In the second variation, the pattern of line-ending words returns to the starting sequence in the eleventh stanza; thus it does not, unlike the "single" sestina, allow for every end-word to occupy each of the stanza ends; end-words 5 and 10 fail to couple between stanzas.

Effect

The structure of the sestina, which demands adherence to a strict and arbitrary order, produces several effects within a poem. Stephanie Burt notes that, "The sestina has served, historically, as a complaint", its harsh demands acting as "signs for deprivation or duress".[17] The structure can enhance the subject matter that it orders; in reference to Elizabeth Bishop's A Miracle for Breakfast, David Caplan suggests that the form's "harshly arbitrary demands echo its subject's".[43] Nevertheless, the form's structure has been criticised; Paul Fussell considers the sestina to be of "dubious structural expressiveness" when composed in English and, irrespective of how it is used, "would seem to be [a form] that gives more structural pleasure to the contriver than to the apprehender".[44]

Margaret Spanos highlights "a number of corresponding levels of tension and resolution" resulting from the structural form, including: structural, semantic and aesthetic tensions.[45] She believes that the aesthetic tension, which results from the "conception of its mathematical completeness and perfection", set against the "experiences of its labyrinthine complexities" can be resolved in the apprehension of the "harmony of the whole".[45]

The strength of the sestina, according to Stephen Fry, is the "repetition and recycling of elusive patterns that cannot be quite held in the mind all at once".[46] For Shanna Compton, these patterns are easily discernible by newcomers to the form; she says that: "Even someone unfamiliar with the form's rules can tell by the end of the second stanza ... what's going on ...".[47]

Examples

- The 1972 television play Between Time and Timbuktu, based on the writings of Kurt Vonnegut, is about a poet-astronaut who wanted to compose a sestina in outer space. Vonnegut wrote a sestina for the production.[48]

See also

- Canzone, an Italian or Provençal song or ballad, in which the sestina is sometimes included.

- Pentina, a variation of the sestina based on five endwords.

- Villanelle, another type of fixed verse form.

References

- ↑ Eusebi, Mario (1996). L'aur'amara. Rome: Carocci. ISBN 978-88-7984-167-2.

- 1 2 Fry 2007, p. 235

- ↑ Davidson 1910 pp. 18–20

- ↑ Collura, Alessio (2010). Il trovatore Guilhem Peire de Cazals. Edizione Critica. Padova: Master Thesis, University of Padova.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Preminger 1993, p. 1146

- ↑ "Sestina of the Lady Pietra degli Scrovigni". The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 Gasparov 1996 p. 159

- ↑ Stratton 1917, pp. 306, 316, 318

- ↑ Kastner 1903 p. 283

- ↑ Kastner, 1903 pp. 283–4

- ↑ Stanbury, Sarah (2005). "Middle English Religious Lyrics". In Duncan, Thomas Gibson (ed.). A Companion to the Middle English Lyric. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 227–41. ISBN 9781843840657.

- ↑ McNamer, Sarah (2003). "Lyrics and romances". In Wallace, David; Dinshaw, Carolyn (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women's Writing. Cambridge UP. pp. 195–209. ISBN 9780521796385.

- ↑ Barratt, Alexandra, ed. (1992). Women's Writing in Middle English. New York: Longman. pp. 275–77. ISBN 0-582-06192-X.

- ↑ "The Shepheardes Calender: August". University of Oregon. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ↑ Shapiro 1980, p. 185

- 1 2 Ferguson 1996, pp. 188–90

- 1 2 Burt 2007, p. 219

- ↑ Caplan 2006, pp. 19–20

- ↑ White 1887, p xxxix

- ↑ This is the earliest-published sestina reprinted by Gleeson White (White 1887, pp 203–12), and he doesn't mention any earlier ones.

- ↑ Lennard 2006, p. 53

- ↑ Caplan 2006, p. 20

- ↑ "Sestina: Altaforte". The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ↑ Preminger 1993, p. 1147

- ↑ Burt 2007, pp. 218–19

- ↑ Kellaway, Kate (26 October 2013). "Six Bad Poets by Christopher Reid – review". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ↑ Wheldon, Wynn (26 September 2013). "Six Bad Poets, by Christopher Reid – review". The Spectator. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ↑ "The Guest Ellen at the Supper for Street People". The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ↑ Fry 2007, p. 231

- ↑ Spanos 1978, p. 546

- ↑ Fry 2007, p. 232

- ↑ Kastner 1903, p. 284

- ↑ Strand et al., 2001, p. 24

- ↑ Burt 2007, p. 222

- ↑ Canettieri, Paolo (1996). Il gioco delle forme nella poesia dei trovatori. Rome: Il Bagatto. ISBN 88-7806-095-X.

- ↑ Krysl 2004, p. 9

- ↑ Shapiro 1980 pp. 7–8

- ↑ Fry 2007, pp. 234–5

- ↑ Fry 2007, p. 234

- ↑ Fry 2007, p. 237

- ↑ Ferguson 1996, p. 1413–13

- ↑ "The Complaint of Lisa". The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ↑ Caplan 2006, p. 23

- ↑ Fussell 1979, p. 145

- 1 2 Spanos 1987, p. 551

- ↑ Fry 2007, p. 238

- ↑ Burt 2007, p. 226

- ↑ Vonnegut, Kurt (2012). Wakefield, Dan (ed.). Kurt Vonnegut: Letters. New York: Delacorte Press. ISBN 9780345535399.

I am writing a sestina for the script... It's tough, but what isn't?

(Letter of 2 October 1971, to his daughter Nanette.)

Sources

- Burt, Stephen (2007). "Sestina! or, The Fate of the Idea of Form" (PDF). Modern Philology. 105 (1): 218–241. doi:10.1086/587209. JSTOR 10.1086/587209. S2CID 162877995. (subscription required)

- Canettieri, Paolo (1996). Il gioco delle forme nella lirica dei trovatori. IT: Bagatto Libri.

- Caplan, David (2006). Questions of possibility: contemporary poetry and poetic form. US: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531325-3.

- Davidson, F. J. A. (1910). "The Origin of the Sestina". Modern Language Notes. 25 (1): 18–20. doi:10.2307/2915934. JSTOR 2915934. (subscription required)

- Ferguson, Margaret; et al. (1996). The Norton Anthology of Poetry. US: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-393-96820-0.

- Fry, Stephen (2007). The Ode Less Travelled. UK: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-09-950934-9.

- Fussell, Paul (1979). Poetic Meter and Poetic Form. US: McGraw-Hill Higher Education. ISBN 978-0-07-553606-2.

- Gasparov, M. L. (1996). A History of European Versification. UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815879-0.

- Kastner, L. E. (1903). A History of French Versification. UK: Clarendon Press.

- Krysl, Marilyn (2004). "Sacred and Profane: Sestina as Rite". The American Poetry Review. 33 (2): 7–12.

- Lennard, John (2006). The Poetry Handbook. UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926538-1.

- Preminger, Alex; et al. (1993). The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics. US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02123-6.

- Shapiro, Marianne (1980). Hieroglyph of time: the Petrarchan sestina. US: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-0945-1.

- Spanos, Margaret (1978). "The Sestina: An Exploration of the Dynamics of Poetic Structure". Medieval Academy of America. 53 (3): 545–557. doi:10.2307/2855144. JSTOR 2855144. S2CID 162823092. (subscription required)

- Strand, Mark; Boland, Eavan (2001). The Making of a Poem: A Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms. US: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32178-4.

- White, Gleeson, ed. (1887). Ballades and Rondeaus, Chants Royal, Sestinas, Villanelles, etc. The Canterbury Poets. The Walter Scott Publishing Co., Ltd.

Further reading

- Saclolo, Michael P. (May 2011). "How a Medieval Troubadour Became a Mathematical Figure" (PDF). Notices of the AMS. 58 (5): 682–7. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- Stratton, Clarence (1917). "The Italian Lyrics of Sidney's Arcadia". The Sewanee Review. 25 (3): 305–326. JSTOR 27533030. (subscription required)

External links

- Rules and history of the sestina from the American Academy of Poetry

- Examples of sestinas from 2003–2007 at McSweeney's Internet Tendency

- How to Write a Sestina (with Examples and Diagrams) from the Society of Classical Poets