.jpg.webp)

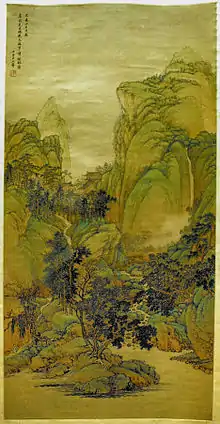

Shan shui (Chinese: 山水; pinyin: shān shuǐ; lit. 'mountain-water'; pronounced [ʂán ʂwèɪ]) refers to a style of traditional Chinese painting that involves or depicts scenery or natural landscapes, using a brush and ink rather than more conventional paints. Mountains, rivers and waterfalls are common subjects of shan shui paintings.

History

Shan shui painting first began to develop in the 5th century,[1] in the Liu Song dynasty.[2] It was later characterized by a group of landscape painters such as Zhang Zeduan,[3] most of them already famous, who produced large-scale landscape paintings. These landscape paintings usually centered on mountains. Mountains had long been seen as sacred places in China,[4] which were viewed as the homes of immortals and thus, close to the heavens. Philosophical interest in nature, or in mystical connotations of naturalism, could also have contributed to the rise of landscape painting. The art of shan shui, like many other styles of Chinese painting has a strong reference to Taoism/Daoism imagery and motifs,[5] as symbolisms of Taoism strongly influenced "Chinese landscape painting".[5] Some authors have suggested that Daoist stress on how minor the human presence is in the vastness of the cosmos, or Neo-Confucian interest in the patterns or principles that underlie all phenomena, natural and social lead to the highly structuralized nature of shan shui.[6]

Concepts

Most dictionaries and definitions of shan shui assume that the term includes all ancient Chinese paintings with mountain and water images.[3] Contemporary Chinese painters, however, feel that only paintings with mountain and water images that follow specific conventions of form, style and function should be called "shan shui painting".[4][6] When Chinese painters work on shan shui painting, they do not try to present an image of what they have seen in the nature, but what they have thought about nature. No one cares whether the painted colors and shapes look like the real object or not.[3]

According to Ch'eng Hsi:

Shan shui painting is a kind of painting which goes against the common definition of what a painting is. Shan shui painting refutes color, light and shadow and personal brush work. Shan shui painting is not an open window for the viewer's eye, it is an object for the viewer's mind. Shan shui painting is more like a vehicle of philosophy.[6]

Compositions

Shan shui paintings involve a complicated and rigorous set of almost mystical requirements[7] for balance, composition, and form. All shan shui paintings should have 3 basic components:

Paths – Pathways should never be straight. They should meander like a stream. This helps deepen the landscape by adding layers. The path can be the river, or a path along it, or the tracing of the sun through the sky over the shoulder of the mountain.[3] The concept is to never create inorganic patterns, but instead to mimic the patterns that nature creates.

The Threshold – The path should lead to a threshold. The threshold is there to embrace you and provide a special welcome. The threshold can be the mountain, or its shadow upon the ground, or its cut into the sky.[3] The concept is always that a mountain or its boundary must be defined clearly.

The Heart – The heart is the focal point of the painting and all elements should lead to it. The heart defines the meaning of the painting.[3] The concept should imply that each painting has a single focal point, and that all the natural lines of the painting direct inwards to this point.

Elements and colors

While many landscape paintings in China uses only ink or uses color for aesthetic purposes, some Shan shui are painted and designed in accordance with Chinese elemental theory with five elements or phases representing various parts of the natural world, and thus has specific directions for colorations that should be used in 'directions' of the painting, as to which should dominate.[8]

| Direction | Element | Colour |

|---|---|---|

| East | Wood | Green |

| South | Fire | Red |

| NE / SW | Earth | Tan or Yellow |

| West / NW | Metal | White or gold |

| North | Water | Blue or Black |

Positive interactions between the Elements are:

- Wood produces Fire

- Fire produces Earth

- Earth produces Metal

- Metal produces Water

- Water produces Wood.

Elements that react positively should be used together. For example, Water complements both Metal and Wood; therefore, a painter would combine blue and green or blue and white. There is a positive interaction between Earth and Fire, so a painter would mix Yellow and Red.[4]

Negative interactions between the Elements are:

- Wood uproots Earth

- Earth blocks Water

- Water douses Fire

- Fire melts Metal

- Metal chops Wood

Elements that interact negatively should never be used together. For example, Fire will not interact positively with Water or Metal so a painter would not choose to mix red and blue, or red and white.[2]

Connection to poetry

A certain movement in poetry, influenced by the shan shui style, came to be known as Shanshui poetry. Sometimes, the poems were designed to be viewed with a particular work of art, others were intended to be "textual art" that invoked an image inside a reader's mind.[9]

Influence

Animation and film

The art form of shan shui has been popular to the point where a Chinese animation from 1988 entitled Feeling from Mountain and Water uses the same art style and even the term for the film's title. Additionally, many recent movies and plays produced in China, specifically House of Flying Daggers and Hero, use elements of the style itself in the sets, as well as the elemental aspects in providing "balance".[10]

Construction

The term shan shui is sometimes extended to include gardening and landscape design, particularly within the context of feng shui.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Wen Fong (1992). Beyond Representation: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, 8th–14th Century. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-300-05701-0.

- 1 2 Textual Evidence for the Secular Arts of China in the Period from Liu Sung through Sui (1967) by Alexander Soper

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sirén, Osvald (1956). Chinese Painting: Leading Masters and Principles. Ronald Press. pp. 62, 104.

- 1 2 3 Yee, Chiang; S.I. Hsiung (1964). The Chinese eye: An interpretation of Chinese painting. Indiana University Press.

- 1 2 Northrop, Filmer Stuart Cuckow (1949). Ideological Differences and World Order: Studies in the Philosophy and Science of the World's Culture. Yale University Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-8371-5228-3.

- 1 2 3 Robert J. Maeda; et al. (1970). Two Twelfth Century Texts on Chinese Painting. University of Michigan, Center for Chinese Studies. p. 16. ISBN 0-89264-008-1.

- ↑ Wicks, Robert 1954 – "Being in the Dry Zen Landscape", The Journal of Aesthetic Education – Volume 38, Number 1, Spring 2004, pp. 112–122

- ↑ Early Chinese Texts on Painting by Susan Bush, Hsio-yen Shih. Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews, Vol. 7, No. 1/2 (Jul., 1985), pp. 153–159

- ↑ Chu-chin Sun, Cecile (1995). Pearl from the Dragon's Mouth: Evocation of Scene and Feeling in Chinese Poetry. University of Michigan: Center for Chinese Studies. p. 43. ISBN 9780892641109.

- ↑ Berry, Michael (2005). Speaking in Images: Interviews with Contemporary Chinese Filmmakers. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231133319.

- ↑ Birmingham Museum of Art (1984). Landscape Painting in Contemporary China. Birmingham, Alabama: Birmingham Museum of Art. ISBN 9780931394164.

External links

- Chinese Landscape Painting at China Online Museum

- Chinese Painters and Galleries at China Online Museum