| Mausoleum of Genghis Khan | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Main hall | |||||||||

| Chinese | 成吉思汗陵 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | Burial mound of Genghis Khan | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Mausoleum of Genghis Khan is a mausoleum dedicated to Genghis Khan, where he is worshipped as ancestor, dynastic founder, and deity. The mausoleum is better called the Lord's Enclosure (i.e. shrine), the traditional name among the Mongols, as it has never truly contained the Khan's body. It is the main centre of the worship of Genghis Khan, a growing practice in the Mongolian shamanism of both Inner Mongolia, where the mausoleum is located, and Mongolia.[1]

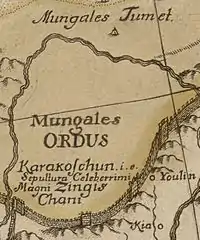

The mausoleum is located in the Kandehuo Enclosure in the town of Xinjie,[2] in the Ejin Horo Banner in the Ordos Prefecture of Inner Mongolia, in China. The main hall is actually a cenotaph where the coffin contains no body (only headdresses and accessories), because the actual tomb of Genghis Khan has never been discovered.

The present structure was built between 1954 and 1956 by the government of the People's Republic of China in the traditional Mongol style. It was desecrated and its relics destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, but it was restored with replicas in the 1980s and remains the center of Genghis Khan worship. It was named a AAAAA-rated tourist attraction by China's National Tourism Administration in 2011.

Location

The cenotaph is located at an elevation of 1,350 m (4,430 ft)[3] on the Gandeli[4] or Gande'er Prairie[5] about 15 km (9.3 mi) southeast of Xilian and about 30 km (19 mi) south of the county seat of Ejin Horo Banner, Inner Mongolia.[5] It is the namesake of its surrounding banner, whose name translates from Mongolian as "the Lord's Enclosure".[6]

The site is 115 km (71 mi) north of Yulin; 55 km (34 mi) south of Dongsheng; and 185 km (115 mi) from Baotou.[5] There is a new interchange on highway 210 leading directly to the site.[lower-alpha 1]

History

Early sites

After Genghis Khan died in or around Gansu[7] on 12 July AD 1227,[8] his remains were supposedly carried back to central Mongolia and buried secretly and without markings, in accordance with his personal directions. His actual burial site remains unknown but was almost certainly not in Ejin Horo, which had only recently been conquered from the Tangut Empire.[9] Without a body, the Mongols honored the khan's memory and spirit through his personal effects. These ceremonies allegedly date to the same year as his death.[3] Kublai Khan built temples for his grandfather's cult in Daidu and Shangdu.[10] Nine "palaces" for rituals concerning his cult were maintained by an imperial official in Karakorum.[11]

After the fall of the Yuan in 1368,[10] these permanent structures were replaced by portable mausoleums called the "eight white yurts" (naiman tsagaan ger). These had originally been palaces where the khan had lived, but were altered to mausoleums by Ögedei Khan. These yurts were first encamped at Avraga site at the base of the Khentii Mountains in Delgerkhaan in Mongolia's Khentii Province.

Ordos

The shrine was entrusted to caretakers known as the Darkhad. Their leader was chosen from the Borjigin clan and was known as the Jinong since the first, Kamala, had been appointed King of Jin. The Darkhad moved from the Kherlen River to the Ordos, which took its name (Mongolian for "palaces") from the mausoleum's presence there. The caretakers oversaw commemorative and religious rituals and were visited by pilgrims. Mongol khans were also crowned at the yurts.

Under the Qing, 500 Darkhad were exempted from military service and taxation; the shrine also received 500 taels (about 16–17 kg or 35–37 lb) of silver each year to maintain its rituals.[12] The site's rituals became more local, more open to lower-class people, and more Buddhist.[13]

The Mongolian prince Toghtakhutörü and the Darkhad built a permanent mausoleum in Setsen Khan Aimag in 1864. This traditional Chinese structure was described by a Belgian missionary in 1875[14] but was destroyed at the Panchen Lama's suggestion in order to end an outbreak of plague among the Darkhad in early 20th century.[14]

Around the fall of the Qing, the mausoleum became notable as a symbol for Mongolian nationalists. The Buryat scholar Tsyben Zhamtsarano advocated a removal of the shrine to northern Mongolia c. 1910. After the Mongolian Revolution, a sacrificial rite was held for Genghis Khan to "bring peace and safety to... human beings and other creatures" and to "drive out bandits, thieves, illness, and other internal and external malefactions" in 1912.[15] Some Mongolians planned to remove some of the ritual objects—particularly the Black Sülde, an allegedly magical heaven-sent trident[16]—to the independent northern Mongolian territory from the Inner Mongolian shrine;[17] in 1914, a letter from the Beijing office overseeing Mongolia and Tibet ordered Arbinbayar, the head of the Ihe Juu League, that

[As] the Black Sülde has been an object of veneration associated with Genghis Khan since the Yuan Dynasty and has been worshipped in our China for some thousand years, it is therefore definitely not allowed that it should be given to those stupid Khalkha who rudely fail to understand the reasoning of Heaven.[17]

In 1915, Zhang Xiangwen (t 張相文, s 张相文, p Zhāng Xiāngwén, w Chang Hsiang-wen) began the scholarly controversy over the site of Genghis Khan's tomb[18] by publishing an article claiming that it was in Ejin Horo.[19]

During World War II, Prince Demchugdongrub, the notional leader of the Japanese puppet government in Mongolia, ordered that the mobile tomb and its relics be moved to avoid a supposed "Chinese plot to plunder it".[20] This was rebuffed by the local leader Shagdarjab, who claimed that the shrines could never be moved and locals would resist any attempt to do so.[20] When he accepted Japanese weaponry to defend it, however, the Nationalist government became alarmed at the possibility of Japan using the cult of Genghis Khan[20] to lead a Mongolian separatist movement. The yurts and their relics were to be removed to Qinghai either at their armed insistence or at Shagdarjab's invitation. (Accounts differ.)[20] The Japanese still attempted to use the cult of Genghis Khan to fan Mongolian nationalism; from 1941–4,[21] the IJA colonel Kanagawa Kosaku constructed a separate mausoleum in Ulan Hot consisting of 3 main buildings in a 6 hectares (15 acres) estate.[21]

Gansu

Once in Chinese hands, the relics did not go to Qinghai as planned. On 17 May 1939,[22] 200 specially-selected Nationalist troops conveyed the relics to Yan'an, then the principal base of the Chinese Communists.[20] Upon their arrival on 21 June 1939, the Communists held a large public sacrifice to Genghis Khan with a crowd of about ten thousand spectators; the Central Committee presented memorial wreathes; and Mao Zedong produced a new sign for it in his calligraphy, reading "Genghis Khan Memorial Hall" (t 成吉思汗紀念堂, s 成吉思汗纪念堂, Chéngjísī Hán Jìniàntáng).[20] As part of the Second United Front, it was allowed to pass out of the Communist controlled area to Xi'an, where Shaanxi governor Jiang Dingwen officiated another religious ritual before a crowd of tens of thousands on 25 June. (Accounts vary from thirty to 200,000.)[20] Li Yiyan, a member of the Nationalists' provincial committee, wrote the booklet China's National Hero Genghis Khan (t 《中華民族英雄成吉思汗》, s 《中华民族英雄成吉思汗》, Zhōnghuá Mínzú Yīngxióng Chéngjísī Hán) to commemorate the event, listing the khan as a great Chinese leader in the mold of the First Emperor, Emperor Wu, and Emperor Taizong.[23] A few days later, the Gansu governor Zhu Shaoliang held a similar ritual[24] before enshrining the khan's relics at the Dongshan Dafo Dian[25] on Xinglong Mountain in Yuzhong County.[24] The Gansu government sent soldiers and a chief official for the shrine and brought the remaining Darkhad onto the provincial government's payroll;[24] the original 500 Darkhad were reduced to a mere seven or eight. Following this 900 km (560 mi) journey,[26] the shrine remained there for ten years.[24]

Qinghai

At the conclusion of the Chinese Civil War, the Nationalist guard at the temple fled before the Communist advance into Gansu in the summer of 1949.[24] Plans were put forward to move the khan's shrine to the Alxa League in western Inner Mongolia or to Mount Emei in Sichuan.[24] Ultimately, Qinghai's local warlord Ma Pufang intervened[24] and moved it 200 km (120 mi) west to Kumbum Monastery near his capital Xining, consecrating it with the help of local and Mongolian lamas under Ulaan Gegen.[24] Following the Communist conquest of Xining a few months later, the Communist general He Banyan sacrificed three sheep to the khan and offered ceremonial scarves (hadag) and a banner reading "National Hero" (民族英雄, Mínzú Yīngxióng) to the temple housing his shrine.[10]

Present-day mausoleum

Ejin Horo fell to the Communists at the end of 1949 and was controlled by their Northwest Bureau until the establishment of Suiyuan Province the next year.[10] The district's Communists set up rituals honouring Genghis Khan in the early 1950s, but abolished the traditional religious offices surrounding them like the Jinong and controlled the cult through local committees with loyal Party cadres.[10] Without the relics, they relied largely on singing and dancing groups.[10] In 1953, the PRC's central government approved the recently-formed Inner Mongolian provincial government's request for 800,000 RMB to create the present permanent structures.[3] Early the next year,[15] the central government permitted the return of the objects at Kumbum to the site being constructed at Ejin Horo.[10] The region's chairman Ulanhu officiated at the first ritual after their return, decrying the Nationalists for having "stolen" them.[10] After this ritual, he immediately held a second ceremony to break ground on a permanent temple to house the objects and the khan's cult, again approved and paid for by China's central government.[10] By 1956, this new temple was completed, greatly expanding the purview of the original shrine.[14] Rather than having eight separate shrines throughout Ejin Horo for the Great Khan, his wives, and his children, all were placed together; a further 20 sacred and venerated objects from around the Ordos were also brought to the new site.[14] The government also mandated that the main ritual would be held in the summer rather than in the third lunar month, in order to make it more convenient for the headers to maintain their spring work schedules.[14] With the Darkhads no longer liable for personally paying for maintenance of the shrine, most accepted these changes.[14] An especially large celebration was held in 1962 to mark the 800th anniversary of Genghis Khan's birth.[15]

In 1968, the Cultural Revolution's Red Guards destroyed almost everything of value at the shrine.[14] For 10 years, the buildings themselves were turned into a salt depot as part of preparations for a potential war with the Soviet Union.[27]

Following Deng Xiaoping's Opening Up Policy, the site was restored by 1982[3] and sanctioned for "patriotic education"[14] as a AAAA-rated tourist attraction.[3] Replicas of the former relics were made, and a great marble statue of Genghis was completed in 1989.[28] Priests at the museum now claim that all of the Red Guards who desecrated the tomb have died in abnormal ways, suffering a kind of curse.[29]

Inner Mongolians continued to complain about the poor state of the mausoleum.[30] A 2001 proposal for its refurbishment was finally approved in 2004.[30] Unrelated houses, stores, and hotels were removed from the area of the mausoleum to a separate area 3 km (1.9 mi) away and replaced with new structures in the same style as the mausoleum.[30] The 150-million-RMB (about $20 million)[31] improvement plan was carried out from 2005 to 2006, improving the site's infrastructure, expanding its courtyard, and decorating and repairing its existing buildings and walls.[32] The China National Tourism Administration named the site a AAAAA-rated tourist attraction in 2011.[33]

On 10 July 2015,[34] 20 tourists aged 33 to 74—10 South Africans, 9 Britons, and an Indian[35]—were detained at Ordos Ejin Horo Airport, arrested on terrorism-related charges the next day,[36] and ultimately deported from China[37] after they watched a BBC documentary about Genghis Khan in their hotel rooms prior to visiting the mausoleum.[38] Authorities had considered it "watching and spreading violent terrorist videos".[37]

In 2017, the Genghis Khan Mausoleum averaged about 8000 visitors a day during its peak season and about 200 visitors a day at other times.[39]

Administration

The site is overseen by the Genghis Khan Mausoleum Administration Bureau.[40] It was headed by Chageder and then Mengkeduren in the early 2000s.[30]

Architecture

The present Genghis Khan Mausoleum Scenic Area stretches about 15 km × 30 km (9.3 mi × 18.6 mi), covering about 225 km2 (87 sq mi) in total.[40][5] It consists of the Sulede Altar, the Sightseeing District for the Protection of Historic Relics, the Conservation District for Ecosystem Preservation, the Development-Restricted District of Visual Spectacles, the 4 km (2.5 mi) long Sacred Pathway of Genghis Khan between the entrance and the cenotaph, the 16 km (9.9 mi) long scenic pathway around the Bayinchanghuo Prairie, a Tourist Activity Centre, a Tourist Education Centre, the Sacrificial Sightseeing District, the Mongolian Folk Custom Village, the Shenquan Ecological Tourism Region, the Nadam Equestrian Sport Centre, and the Hot Air Balloon Club.

The tomb complex consists of the Main Hall, the Imperial Burial Palace, the Western Hall, the Eastern Hall, the Western Corridor, and the Eastern Corridor.

The Main Hall (正殿) is octagonal,[4] 24.18 m (79.3 ft) high,[3] and covers about 2,000 m2 (0.49 acres).[3] It is shaped like a flying eagle as a symbol of the khan's bravery and adventurousness.[3] Its plaque, reading "Mausoleum of Genghis Khan", was written by Ulanhu in 1985.[3] The site includes a 5 m (16 ft) high statue of Genghis Khan and two murals about his life, including a wall map of the extent of the Mongol Empire.[4]

The Imperial Burial Palace (寢宮) or Back Palace[5] (後殿) is 20 m (66 ft) high and covers about 5.5 ha (14 acres).[7] It has three yurts with yellow silk roofs; the central yurt houses the coffins of Genghis Khan and one of his four wives[3] and the side yurts house the coffins of his brothers. Genghis Khan's coffin is silver decorated with engraved roses and a golden lock; weapons allegedly used by Genghis lie around it. There are also two other coffins for another two of his consorts. The site's main altar lies in front of this yurt.[4] The cenotaph and its placement are highly unusual in China, which usually follows Han principles like feng shui in the placement of tombs, employing mountains, rivers, and forests[4] in the belief that this increases its spiritual power.

The Eastern Hall or Palace (東殿) is 20 m (66 ft) high. It holds the coffin of Tolui (Genghis Khan's 4th and favourite son) and his wife Sorghaghtani.

The Western Hall or Palace (西殿) is 23 m (75 ft) high. It holds nine banners with holy arrows thought to house or connect with the soul of the Great Khan.[4] They also represent 9 of Genghis's generals. It also holds Genghis's saddle and reins,[3] some weapons,[5] and some other objects like the khan's milk barrel.[3] All of the items currently displayed are replicas.[41]

The 20 m (66 ft) high Eastern (東廊) and Western Corridors (西廊) connecting these halls are decorated with 150 m2 (1,600 sq ft) of murals[4] about the lives of Genghis Khan and his descendants.

The site uses a five-colour scheme of blue, red, white, gold, and green to represent the multiethnic nature of Genghis Khan's empire and also the sky, sun and fire, milk, earth, and prairie.[3]

Worship

Genghis Khan worship is a practice of Mongolian shamanism.[42] There are other mausoleums dedicated to this cult in Inner Mongolia and Northern China.[43][44]

The mausoleum is guarded by the Darkhad or Darqads[24] ("Untouchables"), who also oversee its religious festivals, stop tourists from taking photographs,[39] keep candles lit,[39] and watch over the site's keys and books.[39] The 30 or so official Darkhad at the mausoleum are paid about 4000 RMB a month for their services.[39]

Mongols gather four times annually:[4]

- 21st day of the 3rd month of the Mongolian calendar, the most important[5]

- 15th day of the 5th lunar month

- 12th day of the 9th lunar month

- Goat Hide Stripes Ceremony on the 3rd day of the 10th lunar month[45]

There is also a major ceremony in honor of the Black Sülde on the 14th day of the 7th lunar month.[16]

They follow traditional ceremonies, such as offering flowers and food to Heaven (Tengri). The ritual sacrifice to the spirit of Genghis Khan was listed as national-level intangible cultural heritage in 2006, and the sacrifice to the Black Sülde was given similar status at the provincial level in 2007.[3] After the ceremonies, there are Naadam competitions, primarily wrestling, horse-riding, and archery,[46] but also singing.[47]

Performance

The mausoleum complex is also hosts three plays concerning the khan and Mongolian culture: Proud Son of Heaven: Eternal Genghis Khan,[48] The Mighty Genghis Khan (《永远的成吉思汗》), or The Grand Ceremony of Genghis Khan (《成吉思汗大典》),[4][49] and An Ordos Wedding Ceremony (《鄂尔多斯婚礼》).[50] There is also an annual Genghis Khan Mausoleum Tourism Cultural Week.[48]

Notes

- ↑ Its coordinates are 39°20′10″N 109°50′23″E / 39.33611°N 109.83972°E.

References

Citations

- ↑ Man (2004), p. 22.

- ↑ "Mausoleum of Genghis Khan". China & Asia Cultural Travel. 23 October 2015. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "A Brief Introduction of Genghis Khan". Ordos: Mausoleum of Genghis Khan. Archived from the original on 2018-01-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Absolute Tours (2013).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Li (2006).

- ↑ Man (2004), p. 286.

- 1 2 Liu (2010).

- ↑ "Events of Genghis Khan". Ordos: Mausoleum of Genghis Khan. Archived from the original on 2018-01-29.

- ↑ Su (1994), p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bayar (2007), p. 210.

- ↑ Bayar (2007), p. 198.

- ↑ Bayar (2007), p. 203.

- ↑ Bayar (2007), p. 203–4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bayar (2007), p. 211.

- 1 2 3 Bayar (2007), p. 212.

- 1 2 Xinhua (2006).

- 1 2 Bayar (2007), p. 206.

- ↑ Su (1994), p. 4.

- ↑ Zhang (1915).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bayar (2007), p. 208.

- 1 2 Man (2004), p. 370.

- ↑ Man (2004), p. 296.

- ↑ Bayar (2007), p. 208–9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bayar (2007), p. 209.

- ↑ Man (2004), p. 298.

- ↑ Man (2004), p. 297–8.

- ↑ Man (2004), p. 308.

- ↑ Man (2004), p. 338.

- ↑ Man (2004), p. 312.

- 1 2 3 4 China Daily (2004).

- ↑ Osborn (2005).

- ↑ Xinhua (2005).

- ↑ "AAAAA级景区" (in Chinese). Beijing: China National Tourism Administration. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14..

- ↑ Press Association (2015).

- ↑ Tran et al. (2015).

- ↑ Lin et al. (2015).

- 1 2 Halliday (2015).

- ↑ Associated Press (2015).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ndukong (2017).

- 1 2 Bayar (2007), p. 197.

- ↑ Lonely Planet.

- ↑ Man (2004), pp. 402–404.

- ↑ "成吉思汗召(全)" [Call of Genghis Khan (full)] (in Chinese). 24 July 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-07-24.

- ↑ "成吉思汗祠" [Genghis Khan Temple] (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2017-08-12.

- ↑ Su (1994), p. v.

- ↑ "Nadam Fair". Ordos: Mausoleum of Genghis Khan. Archived from the original on 2018-01-29.

- ↑ Almaz Khan (1995).

- 1 2 Ordos Online.

- ↑ "Song and Dance Drama about Genghis Khan". Ordos: Mausoleum of Genghis Khan. Archived from the original on 2018-01-29.

- ↑ "Ordos Wedding Ceremony". Ordos: Mausoleum of Genghis Khan. Archived from the original on 2018-01-29.

Sources

- "The Mausoleum of Genghis Khan", Absolute China Tours, Hangzhou: Jiedeng Tourism Group, 2013.

- Associated Press (19 July 2015), "UK Tourists Say They Were Deported from China after Watching Genghis Khan Film", The Guardian, London: Guardian News & Media.

- "Tomb of Genghis Khan to Be Renovated", China Daily, Beijing: China Daily Information Co., 29 December 2004

- "Genghis Khan Mausoleum", Lonely Planet, London, 2017

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - "Genghis Khan's Mausoleum", Ordos Online, Ordos: Ordos Municipal People's Government, archived from the original on 2018-02-01, retrieved 2018-01-30.

- Press Association (18 July 2015), "British Tourists Arrested in Northern China to Be Deported", The Guardian, London: Guardian News & Media.

- Xinhua (5 May 2005), "Genghis Khan's Mausoleum under Renovation", Official site, Beijing: China Internet Information Center.

- Xinhua (8 August 2006), "Genghis Khan's Mausoleum Holds Grand Memorial Ceremony", Official site, Beijing: China Internet Information Center.

- Almaz Khan (1995). "Chinggis Khan, From Imperial Ancestor to Ethnic Hero". In Harrell, Stevan (ed.). Cultural Encounters on China's Ethnic Frontiers. University of Washington Press. pp. 248–277. ISBN 9780295973807.

- Bayar, Nasan (2007), "On Chinggis Khan and Being Like a Buddha: A Perspective on Cultural Conflation in Contemporary Inner Mongolia", The Mongolia–Tibet Interface: Opening New Research Terrains in Inner Asia, Brill's Tibetan Studies Library, Vol. 10/9, Proceedings of the 10th Seminar of the IATS, Oxford, 2003, Leiden: Brill, pp. 197–222, ISBN 9789004155213.

- Halliday, Josh (16 July 2015), "UK Tourists Detained in China Suspected of 'Spreading Terrorist Videos'", The Guardian, London: Guardian News & Media.

- Li Meng (28 February 2006), "Genghis Khan's Mausoleum", English Service, Beijing: China Radio International, archived from the original on 2006-11-17.

- Lin, Luna; et al. (15 July 2015), "Six British Tourists Detained for 'Terror Links' Are Expelled from China", The Guardian, London: Guardian News & Media.

- Liu Yan (10 November 2010), "Genghis Khan Mausoleum", CCTV, Beijing: SAPPRFT.

- Man, John (2004), Genghis Khan: Life, Death and Resurrection, London: Bantham, ISBN 978-0-553-81498-9.

- Ndukong, Kimeng Hilton (26 June 2017), "Cameroon: China's Cultural Heritage: A Glance Inside Genghis Khan Mausoleum", Cameroon Tribune, Yaounde

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link). - Naran Bilik. "The Worship of Chinggis Khan: Ethnicity, Nation-State and Situational Relativity" (PDF). China: An International Journal, no. 2 (2013): 25. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- Osborn, Andrew (10 May 2005), "The Cult of Genghis Khan", Independent, London: Independent Digital News & Media.

- Su Rihu (1994), The Chinggis Khan Mausoleum and Its Guardian Tribe, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, pp. 1–226.

- Tran, Mark; et al. (17 July 2015), "Genghis Khan Documentary May Have Been Cause of Tourists' Arrest in China", The Guardian, London: Guardian News & Media.

- Zhang Xiangwen (1915), "《成吉思汗圆寝之发现》 [Chéngjísī Hán Yuánqǐn zhī Fāxiàn, The Discovery of Genghis Khan's Mausoleum]", 《地学杂志》 [Dìxué Zázhì, Journal of Geographical Studies] (in Chinese), vol. VI, pp. 7–13

External links

- Brief Introduction of Genghis Khan's Mausoleum (in English, Chinese, and Mongolian), Mausoleum of Genghis Khan, archived from the original on 2018-01-29.

- Map of the site (in Chinese)

- Photos of the rituals on the 21st day of the 3rd lunar month, from China Daily

- Photos of the mausoleum, from People's Daily

- Photos of the mausoleum, from Getty Images