| Silver Streak | |

|---|---|

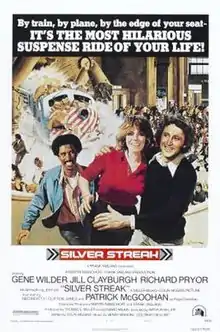

Film poster, artwork by George Gross | |

| Directed by | Arthur Hiller |

| Written by | Colin Higgins |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | David M. Walsh |

| Edited by | David Bretherton |

| Music by | Henry Mancini |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.5 million[2] or $6.5 million[3] |

| Box office | $51.1 million[4] |

Silver Streak is a 1976 American thriller comedy film, about a murder on a Los Angeles-to-Chicago train journey. It was directed by Arthur Hiller and stars Gene Wilder, Jill Clayburgh, and Richard Pryor, with Patrick McGoohan, Ned Beatty, Clifton James, Ray Walston, Scatman Crothers, and Richard Kiel in supporting roles. The film score is by Henry Mancini. This film marked the first pairing of Wilder and Pryor, who were later paired in three other films.[5]

Plot

Book editor George Caldwell, en route to a wedding aboard the Silver Streak, meets salesman Bob Sweet and Hilly Burns, secretary to Rembrandt historian Professor Schreiner. While sharing nightcaps in Hilly's sleeper car, George sees Schreiner's body fall from the train outside her window. Investigating Schreiner's train compartment, George encounters Johnson, Whiney, and Reace: three suspicious individuals who have ransacked Schreiner's belongings. Reace throws George off the train. After walking along the tracks, George meets a farmer and they overtake the train in her biplane.

George sees Hilly with art dealer Roger Devereau and his employees Johnson (impersonating Schreiner), and Whiney. Devereau apologizes to George for the misunderstanding involving Reace, also under his employ. Sweet reveals himself to be an undercover FBI agent named Stevens. The bureau has been investigating Devereau, a criminal who passes himself off as an art expert. Devereau's plan is to discredit Schreiner's book, which would expose Devereau for authenticating forgeries as original Rembrandts. Inside Schreiner's book, George finds letters written by Rembrandt that would prove Devereau's guilt. Reace kills Stevens, thinking he's George. A fight ends on the roof of the train, where George shoots Reace with a harpoon gun before being knocked off by a train signal.

On foot again, George finds the local sheriff, who has trouble making sense of his story. The sheriff says the police are after George for killing Stevens. George escapes, stealing a patrol car that had been transporting car thief Grover T. Muldoon. George and Grover work together to catch up to the train at Kansas City so George can save Hilly from Devereau's crew. Using shoe polish, Grover disguises George as a black man so George can get by police to board the train.

George is captured, but Grover poses as a steward and rescues him and Hilly from Devereau's room. After a shootout, George and Grover jump off the train and are arrested and are taken to a train station, where Stevens' former boss Chief Donaldson had been waiting for George. Donaldson tells George and Grover the police knew George did not kill Stevens and Donaldson was the one who made a cover story in the news for the police to protect George from Devereau. After George explains Devereau's plan, Donaldson has the train stopped. Devereau burns the Rembrandt letters.

George boards the train the fourth time with Grover as Devereau climbs onto the locomotive and shoots the fireman. Donaldson wounds Whiney but is kicked off the train by Devereau and stumbles to his death. George shoots Johnson and Devereau shoots the engineer, placing a toolbox on the dead-man switch to keep the engine running. Devereau is disabled by shots from George and Donaldson, and he is decapitated by an oncoming freight train.

With the death of Devereau and his men, the Silver Streak is now a runaway train. With the help of a porter, George uncouples the back part of the train in order to trigger the brakes. However, the front part of the train still retains enough momentum due to the locomotives being at high throttle, and it roars into Chicago's Central Station, destroying everything in its path until the brakes finally take hold. The rear half of the train follows, gliding safely into the station. Grover steals a Fiat X1/9 and drives away. George and Hilly bid him goodbye and leave to begin their new relationship.

Cast

- Gene Wilder as George Caldwell

- Jill Clayburgh as Hildegarde "Hilly" Burns

- Richard Pryor as Grover T. Muldoon

- Patrick McGoohan as Roger Devereau

- Ned Beatty as FBI Agent Bob Stevens / Bob Sweet

- Clifton James as Sheriff Oliver Chauncey

- Gordon Hurst as Deputy "Moose"

- Ray Walston as Edgar Whiney

- Scatman Crothers as Porter Ralston

- Len Birman as FBI Agent Donaldson

- Lucille Benson as Rita Babtree

- Stefan Gierasch as Professor Arthur Schreiner / Johnson

- Valerie Curtin as Plain Jane

- Richard Kiel as Reace

- Fred Willard as Jerry Jarvis

- Ed McNamara as Benny

- Henry Beckman as Conventioneer

- Harvey Atkin as Conventioneer

- Robert Culp as FBI Agent (uncredited)

- J.A. Preston as The Waiter (uncredited)

Production

.jpg.webp)

The film was based on an original screenplay by Colin Higgins, who at the time was best known for writing Harold and Maude. He wrote Silver Streak "because I had always wanted to get on a train and meet some blonde. It never happened, so I wrote a script."[6]

Higgins wrote Silver Streak for the producers of The Devil's Daughter, a TV film he had written. Both they and Higgins wanted to get into television.[7] The script was sent out to auction. It was set on an Amtrak train and Paramount was interested, but wanted Amtrak to give its approval. Alan Ladd Jr. and Frank Yablans at 20th Century Fox didn't want to wait and bought the script for a then-record $400,000. Ladd said "It was like the old Laurel and Hardy comedies. The hero is Laurel, he falls off the train, stumbles about, makes a fool of himself, but still gets the pretty girl. Audiences have identified with that since Buster Keaton."[2]

Colin Higgins wanted George Segal for the hero – the character's name is George – but Fox preferred Gene Wilder. Ladd reasoned that Wilder was "younger, more identifiable for the younger audience. And he's so average, so ordinary, and he gets caught up in all these crazy adventures." (Wilder was actually older than Segal.)[2]

Colin Higgins claimed the producers did not want Richard Pryor cast because Pryor had recently walked off The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars & Motor Kings; he says the producer at one stage considered casting another black actor as a backup. However, Pryor was very professional during the shoot.[8]

Release

The film had over 400 previews around the United States starting November 28, 1976 in New York City.[9] It had its premiere at Tower East Theater in New York on Tuesday, December 7, 1976 and opened in New York City the following day.[1] It opened in Los Angeles on Friday, December 10 before opening nationwide in an additional 350 theaters on December 22.[1][10][9]

Reception

The film grossed over $51 million at the box office and was praised by critics, including Roger Ebert. It maintains a 79% approval rating at Rotten Tomatoes from 24 reviews.[11] Ruth Batchelor of the Los Angeles Free Press described it as a "fabulous, funny, suspenseful, wonderful, marvelous, sexy, fantastic trip on a train, with the most lovable group of characters ever assembled."[12] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune, however, called the film "a needlessly convoluted mystery yarn, which calls everyone's identity into question except Wilder's." Siskel, who gave the film just two stars, added that "the story isn't easy to follow" and that "I'm still not sure whether Clayburgh's character, secretary to Devereaux, was in on the hustle from the beginning."[13] (Hilly Burns was actually Professor Schreiner's secretary, not Devereaux's.)

Awards and honors

- Academy Award nomination: Best Sound (Donald O. Mitchell, Douglas O. Williams, Richard Tyler, and Harold M. Etherington)[14]

- Nomination: Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy — Gene Wilder

- Writers Guild of America nomination: Best Comedy Written Directly for the Screen – Colin Higgins

- The film was chosen for the Royal Film Performance in 1977.

- In 2000, American Film Institute included the film in AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – #95.[15]

Score and soundtrack

Though the film dates to 1976, Henry Mancini's score was never officially released on a soundtrack album. Intrada Records' 2002 compilation became one of the year's best-selling special releases.[16]

References

- 1 2 3 Silver Streak at the American Film Institute Catalog

- 1 2 3 Higham, Charles (17 July 1977). "What Makes Alan Ladd Jr. Hollywood's Hottest Producer?". New York Times. p. 61.

- ↑ "Aubrey Solomon, Twentieth Century Fox: A Corporate and Financial History, Scarecrow Press, 1989 p258".

- ↑ "Silver Streak, Box Office Information". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ↑ Vincent Canby (1976-12-09). "'Silver Streak' Tarnishes on a Tiring Film Trip". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-10-08. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ↑ "Colin Higgins Discusses His Career". Stanford Daily. 2 February 1979. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ Kilday, Gregg (Apr 20, 1977). "The Producers: A Varied Bunch". Los Angeles Times. p. e8.

- ↑ Goldstein, Patrick (Jan 24, 1981). "HIGGINS: WRITER-DIRECTOR ON HOT STREAK". Los Angeles Times. p. b15.

- 1 2 "'Streak' To Top 'Omen's' 400 Sneaks". Variety. November 24, 1976. p. 24.

- ↑ "The Launching of "Silver Streak" (advertisement)". Variety. November 24, 1976. pp. 16–17.

- ↑ "Rotten Tomatoes: Silver Streak". Archived from the original on 2020-09-25. Retrieved 2023-10-10.

- ↑ Pacheco, Robert; Batchelor, Ruth; Nash, J. I. M.; Balance, Bill; Batchelor, Ruth; Faber, Charles; Warfield, Polly; Jaffe, Larry; Fein, A. R. T.; Hogan, T. I. M.; Ford, Michael C.; Peterson, Melody; Brown, Leonard; Latempa, Susan; Ford, Michael C.; Lemon, Peter; Gentry, Glenn; Kaye, Karen; Stickgold, Arthur; Berry, Jody (1976). "Los Angeles Free Press". Archived from the original on 2021-12-16. Retrieved 2022-04-22.

- ↑ Siskel, Gene (December 23, 1976). "Plot derails murky 'Silver Streak'". Chicago Tribune. p. 2:5.

- ↑ "The 49th Academy Awards (1977) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2011-10-03.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ↑ Soundtrack.net/Top Soundtracks of 2002 Archived 2009-10-10 at the Portuguese Web Archive

External links

![]() Quotations related to Silver Streak at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Silver Streak at Wikiquote

- Silver Streak at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Silver Streak at AllMovie

- Silver Streak at IMDb

- Silver Streak (1976) at Rotten Tomatoes

- Silver Streak at the TCM Movie Database

- Silver Streak on Soundtrack.net

- Making of Silver Streak (1976) – Pre-release promotional "Making Of" documentary about the film.

- Complete copy of script