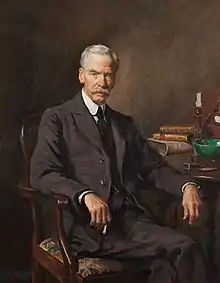

Sir Basil Mott, 1st Baronet, FRS[1] (16 September 1859 – 7 September 1938) was one of the most notable English civil engineers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was responsible for some of the most innovative work on tunnels and bridges in the United Kingdom in the 40-year period centred on World War I.

Early career

Basil Mott was born in Leicester on 16 September 1859. He was educated at the International School, Switzerland and at the Royal School of Mines where he won the Murchison medal in 1879. He was first employed as a mining engineer with the Neston Colliery Co. in Cheshire but in 1886 was invited by J H Greathead to join the staff of the City & South London Railway (C&SLR), for which Greathead was Engineer. His work on the C&SLR gave him a taste for underground construction works that influenced the remaining 40 years of his professional life.

He did well at the C&SLR and was promoted, first to resident engineer (RE) for the extension of the C&SLR from Stockwell to Clapham, then to RE for the entire line. After the railway opened in 1890, he was retained as Engineer by the operating company: this gave him the opportunity to develop techniques for carrying out reconstruction works during overnight possessions of the tunnels, techniques which are still used on LU today.

Shortly after Greathead's death in October 1896, Benjamin Baker formed a partnership with Mott for the design of the Central London Railway. Their association continued with the extensions and rebuilding on the C&SLR (including the underpinning of St Mary Woolnoth church at Bank) and the widening of Blackfriars Bridge. They worked from the same offices until Baker's death in 1907.

Mott, Hay and Anderson

1n 1902, Mott formed what turned out to be a lifelong partnership with another protégé of Baker's, David Hay. Subsequently, the partnership of Mott and Hay (now Mott MacDonald) worked on extending the Central London Railway, the building of escalators in London Underground and the construction of the Tyne and Southwark Bridges. It also designed the underpinning required to stabilise Clifford's Tower in York.

During the first world war, Basil Mott visited France and India, advising the government on solving engineering problems. He was created a Companion of the Bath (CB) in 1918 in recognition of these services.[2]

The Mersey Tunnel, which he worked on between 1922 and 1934, is his most well-known work. From the outset, it was designed on a large scale; it is still the longest, widest road tunnel in Great Britain. Basil Mott was Engineer for the works, in association with J. A. Brodie, Engineer for the City of Liverpool. His partnership (by then named Mott, Hay and Anderson) designed and supervised the construction of the Mersey Tunnel in its entirety.

In 1924, he was elected President of the Institution of Civil Engineers.[3]

In 1926 he was hired by Southampton council to investigate the various options for building a fixed crossing across the lower River Itchen.[4] Along with proving costs for a tunnel and a high level crossing he recommended a low level opening span bridge.[4]

Basil Mott's other post-WW1 works include the extension to Morden of the Northern line, the enlargement of the original C&SLR tunnels from 10' 6" to 11' 8" (using a tunnelling shield which could be worked at night but through which trains could drive during the day), the Jubilee Bridge and work on the Tees Newport Bridge.

In 1930, aged 71, he gave evidence to a British government inquiry on the engineering aspects of a proposed Channel Tunnel (which was not built, though Mott, Hay and Anderson designed the bulk of the successful scheme for Channel Tunnel half a century later). In the same year he was created a baronet.[5]

In May 1932 he became a Fellow of the Royal Society—a rare honour for a civil engineer.[1]

He died on 7 September 1938, in London. The baronetcy is currently held by his great-grandson, David Hugh Mott (born 1952).

References

- 1 2 Gibb, A. (1940). "Sir Basil Mott. 1859-1938". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 3 (8): 23–26. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1940.0004.

- ↑ "No. 30723". The London Gazette (Supplement). 3 June 1918. p. 6528.

- ↑ Watson, Garth (1988), The Civils, London: Thomas Telford Ltd, p. 252, ISBN 0-7277-0392-7

- 1 2 Brian, Adams (1977). The missing link : The story of the Itchen Bridge. Southampton City Council. pp. 30–31.

- ↑ "No. 33622". The London Gazette. 4 July 1930. p. 4181.

Bibliography

- Mott, Hay & Anderson, Consulting Civil Engineers, Newman Neame Ltd., 1965

- Mott MacDonald, The Channel Tunnel; A Designer's Perspective, 1994

- Greathead, J. H., The City and South London Railway – Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Vol 123, 1895

- Mott, B. and Hay, D., Underground Railways in Great Britain, Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers, vol. 54, part F: (1905)

- Anderson, D., Tube Railway Tunnelling, Transactions of the Liverpool Engineering Society, vol. 45, pp. 201–228

- Mersey Tunnels Joint Committee, The Story of the Mersey Tunnel, officially named Queensway, 1934

- Anderson, D., The Construction of the Mersey Tunnel, Paper 5056, Journal of the Institution of Civil Engineers 1935–36, vol. 2, pp 473–544.

- Correspondence about Anderson on Construction of the Mersey Tunnel, Journal of the Institution of Civil Engineers 1935–36, vol. 2, pp 649–660.

- Mott, Hay & Anderson, Some Recent Tunnelling in Great Britain, The Consulting Engineer, December 1949, pp. 344–351