Edward Spears | |

|---|---|

Sir Edward Louis Spears in court uniform c. 21 May 1942 | |

| Born | 7 August 1886 Passy, Paris, France |

| Died | 27 January 1974 (aged 87) Ascot, England |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | British Army |

| Years of service | 1903–1919; 1940–1946 |

| Rank | Major-General |

| Unit | 8th Hussars |

| Awards | Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire 1941, Companion of the Order of the Bath 1919, Military Cross 1915, |

| Relations | Married to Mary ('May') Borden-Turner, one son |

| Other work | Chairman of Ashanti Goldfields 1945–1971; Chairman of Institute of Directors 1948–1966 |

| Member of Parliament for Carlisle | |

| In office 27 October 1931 – 15 June 1945 | |

| Preceded by | George Middleton |

| Succeeded by | Edgar Grierson |

| Member of Parliament for Loughborough | |

| In office 15 November 1922 – 9 October 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Oscar Guest |

| Succeeded by | Frank Rye |

Major-General Sir Edward Louis Spears, 1st Baronet, KBE, CB, MC (7 August 1886 – 27 January 1974) was a British Army officer and Member of Parliament noted for his role as a liaison officer between British and French forces in two world wars. From 1917 to 1920 he was head of the British Military Mission in Paris, ending the war as a Brigadier-General. Between the wars he served as a Member of the British House of Commons, before once again becoming as Anglo-French liaison officer, this time as a Major-General, in the Second World War.

Family and early life

Spears was born of British parents at 7 chaussée de la Muette in the fashionable district of Passy in Paris on 7 August 1886; France would remain the land of his childhood. His parents, Charles McCarthy Spiers and Melicent Marguerite Lucy Hack, were British residents of France. His paternal grandfather was the noted lexicographer, Alexander Spiers, who had published an English-French and French-English dictionary in 1846.[1] The work was extremely successful and adopted by the University of France for French Colleges.[2]

Edward Louis Spears changed his name from Spiers to Spears in 1918. He claimed that the reason was his irritation at the mispronunciation of Spiers, yet it is possible that he wanted an English looking name – something more in keeping with his rank as a brigadier-general and head of the British Military Mission to the French War Office. He denied that he was of Jewish stock, but his great-grandfather had been an Isaac Spiers of Gosport who married Hannah Moses, a shopkeeper of the same town.[3] His ancestry was no secret. In 1918 the French ambassador in London described him as "a very able and intriguing Jew who insinuates himself everywhere."[4]

His parents separated while he was a child, and his maternal grandmother played an important role during his formative years. The young Louis (the name used by his friends) was often on the move, usually with his grandmother – Menton, Aix-les-Bains, Switzerland, Brittany and Ireland. He had contracted diphtheria and typhoid as an infant and was considered delicate. However, after two years at a tough boarding school in Germany, his physical condition improved and he became a strong swimmer and an athlete.[5]

Army service before First World War

In 1903, he joined the Kildare Militia, the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. In the mess, he acquired the nickname of Monsieur Beaucaire after a novel about an urbane Frenchman. The nickname stuck and he was called this by both of his wives, the first of whom would often shorten it to B. In 1906 he was commissioned in the regular army with the 8th Royal Irish Hussars. Spears did not conform to the conventional image of a young army officer. In the same year that he was commissioned, he published a translation of a French general's book, Lessons of the Russo-Japanese War. His upbringing with a succession of tutors meant that he had not learned to mix, and so he did not easily adapt to life in an officers' mess. He could be tactless and argumentative and became an outsider – something he would remain all his life. In 1911, he worked at the War Office developing a joint Anglo-French codebook. In 1914, he published Cavalry Tactical Schemes, another translation of a French military text. In May of the same year, he was sent to Paris to work alongside the French at their Ministry of War with orders to make contact with British agents in Belgium. With the outbreak of war in August 1914, on the orders of his colonel at the War Office, Spears left Paris for the front. Later he would proudly claim that he had been the first British officer at the front.[6]

First World War

Mutual misunderstanding

Cooperation between the French and British armies was severely hampered by a lack of linguistic competence among British and French officers. General Henry Wilson, a staff officer acting as a liaison officer to the French Army, had been said to declare that he saw 'no reason for an officer knowing any language except his own'. According to one story, when Field Marshal Sir John French, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force at the start of the First World War, had spoken (then as a general) from a prepared French text at manoeuvres in France in 1910, his accent was so bad that his listeners thought he was speaking in English.[7]

During the First World War, British soldiers unable to pronounce French words came up with their own (often humorous) versions of place names – the town of Ypres (Ieper in Flemish) was known as 'Wipers'.[8] Yet French place names were also a problem for senior officers. In the spring of 1915, Spears was ordered to pronounce French place names in an English way otherwise General Sir William Robertson, the new Chief of Staff, would not be able to understand them.[9]

On the French side, few of the commanders spoke good English with the exception of Generals Robert Nivelle and Ferdinand Foch. It was in this linguistic fog that the bilingual young subaltern made his mark. Although only a junior officer (a lieutenant of Hussars), he would get to know senior British and French military and political figures (Winston Churchill, Sir John French, Douglas Haig, Joseph Joffre, Philippe Pétain, Paul Reynaud, Robertson etc.) – a fact that would stand him in good stead during later life.[10]

First liaison duties – French Fifth Army

Sent first to the Ardennes on 14 August 1914, his job was to liaise between Field Marshal Sir John French and General Charles Lanrezac, commander of the French Fifth Army. The task was made more difficult by Lanrezac's obsession with secrecy and an arrogant attitude towards the British. The Germans were moving fast and the allied commanders had to make decisions quickly, without consulting each other; their headquarters were also on the move and could not keep their counterparts up to date with their locations. In today's age of radio communication, it is hard to believe that such vital information was often relayed personally by Spears, who travelled by car between the headquarters along roads clogged with refugees and retreating troops.[11]

Commanders were aware that wireless communications were insecure and so often preferred the traditional, personal touch for liaison work. And as far as the telephone was concerned, Spears refers to 'exasperating delays'; sometimes, he was even put through to the advancing Germans by mistake. On these occasions he pretended to be German to extract information, but failed as his German was not sufficiently convincing.[12]

An army is saved

On 23 August, General Lanrezac made a sudden decision to retreat – a manoeuvre that would have dangerously exposed the British forces on his flank. Spears was able to inform Sir John French in the nick of time – the action of a young liaison officer had saved an army. The following day, Spears amazed himself by his audacious language when urging General Lanrezac to launch a counter-attack, "Mon Géneral, if by your action the British Army is annihilated, England will never pardon France, and France will not be able to afford to pardon you." In September, Spears again showed that he was not afraid to speak his mind. When General Louis Franchet d'Espèrey, Lanrezac's successor, had heard (incorrectly) that the British were in retreat, the French officer said 'some unacceptable things concerning the British commander-in-chief in particular and the British in general'. Spears confronted Franchet d'Esperey's chief-of-staff for an apology, which was duly given. At the suggestion of his young liaison officer, Sir John French visited Franchet d'Esperey a few days later to clear up the misunderstanding. Spears remained with the French Fifth Army during the First Battle of the Marne, riding on horseback behind Franchet d'Esperey when Reims was liberated on 13 September.[13]

Liaison duties – French Tenth Army

Spears remained with Franchet d'Esperey after the Battle of the Marne until his posting at the end of September 1914 as liaison officer with the French Tenth Army, which was now under General Louis de Maud'huy near Arras. The two men got on well – Maud'huy referring to him as 'my friend Spears', and insisting that they ate together. It was at the recommendation of the new commander that Spears was made a 'Chevalier de la Légion d'honneur'. In January 1915, he was wounded for the first time and repatriated to convalesce in London. He was mentioned in dispatches and again commended by Maud'huy – as a result he was awarded the Military Cross.[14]

Meets Winston Churchill – a friendship is forged

Again at the front in April 1915, he accompanied Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, on a tour of inspection.[15] Frequently the only Englishman in a French officers' mess, Spears could feel lonely and isolated and had to endure criticism of his country. The general feeling in France was that Britain should be doing more.[16]

When he returned to France after treatment for a second wound which he had incurred in August 1915 (there would be a total of four during the war), he found General Sir Douglas Haig, who was in command of the British First Army, and General Victor d'Urbal, the new commander of the French Tenth Army, at loggerheads; it was his task to improve the relationship. Then on 5 December, the Dardanelles Campaign having failed, Winston Churchill arrived in France seeking a command on the western front. He had lost his post of First Lord of the Admiralty and wanted to temporarily leave the political arena. The two men became friends and Churchill suggested that if he were to be given command of a brigade, Spears might join him as his brigade major. However, Churchill was instead given command of a battalion. In any case, Spears' work in liaison was too highly valued and there was no question that he would be allowed to join Churchill.[17]

Fear of mental breakdown

He got to know General Philippe Pétain, who had distinguished himself at the Battle of Verdun in 1916 and said of him, "I like Pétain, whom I know well." Prior to the Battle of the Somme, he hoped that he would no longer have to face criticism of the British. However, when the British failed and took heavy losses, there were hints that they could not stand shell fire. He began to doubt his fellow countrymen – had they lost the vigour and courage of their forebears? In August 1916, subjected to emotional buffeting from both sides, he feared he might suffer a breakdown.[18]

General Staff – liaison between French Ministry of War and War Office in London

In May 1917, Spears became a major and was promoted to General Staff Officer 1st Grade prior to taking up a high-level appointment in Paris, where he was to liaise between the French Ministry of War and the War Office in London. In less than three years, this young officer had got to know many influential figures on both sides of the Channel. He found Paris full of intrigues, with groups of officers and officials conspiring against each other. Spears exploited the confusion to his advantage and created an independent position for himself.[19]

Within days, Spears was dining at the French War Ministry with a group of VIPs – the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, General Philippe Pétain, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff General Sir William Robertson, Admiral Jellicoe, War Minister Paul Painlevé and Major-General Frederick Maurice, who was the British Director of Military Operations. His brief was to report directly to the War Office in London, bypassing the military attaché. On 17 May, General Pétain, the new French Commander in Chief, told Spears that he wished Lt-General Henry Wilson, who had been closely associated with Petain's disgraced predecessor Nivelle, to be replaced as the chief British liaison officer. Realising this would make Wilson his enemy, Spears protested but was overruled.[20]

Reports on French mutinies and resentment

By 22 May 1917 he had learned of the mutinies in the French Army and travelled to the front to make an assessment. The mutinies had first rumbled during the slaughter at Verdun the previous year (especially during the costly counterattacks by Nivelle and Mangin) and had erupted in earnest after the failure of the Nivelle Offensive in the spring of 1917. Spears was called to London to report on French morale to the War Policy Cabinet Council – a heavy responsibility. Spears recorded in a 1964 BBC interview that Prime Minister David Lloyd George asked repeatedly for assurances that the French would recover. At one point Spears said “You can shoot me if I am wrong – I know how important it is and will stake my life on it." Lloyd George was still not satisfied: “Will you give me your word of honour as an officer and a gentleman that the French Army will recover?”. Spears was so stung by this that he replied "The fact that you ask me that shows you know the meaning of neither".[21]

Spears heard of French dissatisfaction with the British Army's commitment which was expressed on 7 July at a secret parliamentary session. Left wing deputies declared that the British had suffered 300,000 casualties as opposed to 1,300,000 by the French. Furthermore, they were holding a front of 138 kilometres (86 mi), whereas the French held 474 kilometres (295 mi).[22]

In the wake of the Russian Revolution, efforts were made to revive the Eastern Front and detach Bulgaria from the Central Powers. In Paris, Spears worked to promote these ends and received the added task of liaising with the Polish army.[23]

Introduces Churchill to Clemenceau

In November 1917, Georges Clemenceau became Prime Minister of France and restored a will to fight. Spears reported that Clemenceau, who spoke English fluently, was 'markedly pro English'; he was sure that France would last out to the bitter end. Clemenceau had told Spears that he could come to see him at any time – and this he duly did, taking his friend Winston Churchill – now Minister of Munitions – to meet the so-called 'Tiger of France'.[24] Spears became aware of Clemenceau's ruthlessness – 'probably the most difficult and dangerous man I have ever met' – and told London that he was 'out to wreck' the Supreme War Council at Versailles, France, being bent on its domination.[25]

Intrigues in Paris

General Henry Wilson reported Spears as 'one to make mischief'. At the first meeting of the Supreme War Council in December 1917, Spears took the role as a master of ceremonies, interpreting and acting as a go-between. In January 1918, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel and was told he would be made a brigadier-general – the rank that he retained after the war. However, one month later he feared for his career when his enemy, Henry Wilson, replaced General Sir William Robertson as Chief of the Imperial General Staff.[26]

February 1918 saw more intrigues in Paris. General Ferdinand Foch, an ally and friend of General Henry Wilson, would be nominated Allied Supreme Commander in the northern French town of Doullens on 26 March 1918.[27] Foch was concerned at the friendship between his General Alphonse Georges and Louis Spears. Fearing that the latter would know too much, Foch said he would deny the Englishman access to diplomatic dispatches. However, this never came about because Spears played his ace card – the close relationship which he enjoyed with Georges Clemenceau. His adversary General Henry Wilson, the new Chief of the Imperial General Staff, was advised by Foch to 'get rid of Spears'. The complications continued with Spears fighting to maintain his position – telling Wilson that the antagonism of Foch stemmed from personal resentment, and calling upon support from his friend, Winston Churchill. Spears argued that he was attached to Clemenceau and not to Foch – thus his position in Paris was assured, a fact confirmed in due course in a letter from Henry Wilson.[28]

The German offensive of March 1918 forced the allies back and Paris came under artillery bombardment. Mutual recrimination followed, with Field Marshal Douglas Haig raging 'because the French don't help more'; and the French failing to understand 'why the British can't hold'. Paris was a nest of vipers. Both sides were wary of Spears – the French ambassador in London believing him to be a Jew and an intriguer who had wormed his way into the trust of Paul Painlevé (War Minister in the summer of 1917 when Spears had replaced Wilson in French confidence, later Prime Minister from 12 September to 16 November 1917), and that he had passed secrets to the British. By the same token, Spears pointed a finger at Professor Alfred Mantoux, claiming that he was giving information to the French socialist, Albert Thomas. However, Henry Wilson noted that 'Spears is jealous of Mantoux, who is his successful rival as an interpreter.' By the end of May, the Germans were at the River Marne and even Clemenceau turned against Spears. The reason according to Lord Derby, the new ambassador to Paris, was that he 'finds out and tells our government things that Clemenceau does not wish them to know'.[29]

In September 1918, the Germans were in retreat and although praise for Britain came from Foch, the French press was off-hand. Bad feeling towards the British persisted after the armistice on 11 November 1918. In his victory speech to the Chamber of Deputies, Clemenceau did not even mention the British – 'calculated rudeness' according to Spears.[15]

Romance and marriage

Jessie Gordon

In 1908, as a young cavalry officer, Spears suffered concussion after being knocked unconscious during a game of polo. He was treated in London and fell in love with Jessie Gordon, one of the two women running the nursing home where he was a patient. This affair would last for several years – often causing him distress.[30]

Mary 'May' Borden-Turner

In October 1916, just behind the Western Front, he met Mrs Mary Borden-Turner, an American novelist with three daughters who wrote under her maiden name of Mary Borden and was a wealthy heiress. When Spears first met Mary – 'May' as she was known – she had used her money to set up a field hospital for the French army. The attraction was mutual and by the spring of 1917 she and Louis had become lovers. They were married at the British consulate in Paris some three months after her divorce in January 1918.[32] Their only child, Michael, was born in 1921. He contracted osteomyelitis when he was a teenager and ill health would dog him throughout his life. He nevertheless won a scholarship to Oxford University and entered the Foreign Office. However, he suffered from depression and became unable to work, dying at the age of just 47.[33]

The financial security which Spears and May had enjoyed thanks to her family fortune came to an end when she lost her share of the wealth in the Wall Street Crash of 1929.[34]

May resumed her work for the French during the Second World War having established the Hadfield-Spears Ambulance Unit in 1940 with funds from Sir Robert Hadfield, the steel tycoon. The unit was staffed with British nurses and French doctors. May and her unit served in France until the German Blitzkrieg in June 1940 forced them to evacuate to Britain via Arcachon. From May 1941, with funds provided by the British War Relief Society in New York, the medical unit served with Free French forces in the Middle East, North Africa, Italy and France.[35]

_and_Sir_Edward_Spears_in_the_Lebanon%252C_1942.jpg.webp)

In June 1945, a victory parade was held in Paris; Charles de Gaulle had forbidden any British participation. However, vehicles from May's Anglo-French ambulance unit took part – Union Jacks and Tricolours side by side as usual. De Gaulle heard wounded French soldiers cheering, "Voilà Spears! Vive Spears!" and ordered that the unit be closed down immediately and its British members repatriated. May commented, "A pitiful business when a great man suddenly becomes small.".[36] May wrote to General de Gaulle protesting at his order, and speaking in the name of the French officers who had been attached to her unit. The general replied, denying that her unit had been dissolved because of the flying of the British flag; he maintained that a decision had already been taken to dissolve six of the nine mobile surgical units attached to his forces. May's reply of 5 July was bitter: 'From you I have had no recognition since February 1941 [...] but our four years with the 1st Free French Division have bound to us the officers and men of that Division with bonds that can never be broken.'[37] Mary Borden died on 2 December 1968; her obituary in The Times pays tribute to her humanitarian work during both world wars and describes her as 'a writer of very real and obvious gifts'.

Nancy Maurice

Spears resigned his commission in June 1919, thus bringing to an end his post as Head of the Military Mission in Paris. In October of the same year, the former Director of Military Operations in Paris, Sir Frederick Maurice, passed through the city accompanied by his daughter, Nancy. Unlike most girls of her background and station, Nancy had had a good education and was a trained secretary. She agreed to act as Spears' secretary on a temporary basis. However, she would become indispensable and remain in the post for 42 years. Their work brought them close and an affair developed.

When he returned to the Levant in the spring of 1942 after sick leave in Britain, she accompanied him as his secretary. With her good head for commerce, she proved invaluable when he became chairman of the Ashanti Goldfields Corporation in Gold Coast after the war. When May died in December 1968, Nancy expected a speedy marriage but Louis prevaricated. They married on 4 December 1969 at St Paul's Church, Knightsbridge, and Nancy thus became the second Lady Spears. Nancy died in 1975.[38]

Inter-war years

Business and political links with Czechoslovakia

In 1921, Spears went into business with a Finnish partner – their aim was to establish trading links in the newly founded First Czechoslovak Republic. On a visit to Prague, he met Eduard Benes, the Prime Minister, and Jan Masaryk, son of the President; at the same time he came into contact with officials at the Czech Finance Ministry.[39] His business relations in Prague developed further when, in 1934, Spears became chairman of the British Bata shoe company, which, in turn, was part of the international concern of the same name. He later became a director of the merchants, J. Fisher, which had trade links with Czechoslovakia, and a director of a Czech steel works. Yet his business successes found no favour with certain members of the Conservative Party – especially those with anti-Semitic views. Duff Cooper said of him: "He's the most unpopular man in the House. Don't trust him: he'll let you down in the end."[40]

His visits to Czechoslovakia and friendship with its political figures strengthened his resolve to bolster support for the young republic in both London and Paris. He was violently opposed to the Munich agreement of 1938, which saw the Sudetenland handed over to Germany. When he heard the news of the occupation, he wept openly and declared that he had never felt so ashamed and heartbroken. His views brought him into opposition with Conservatives who were broadly in favour of the Munich agreement. Yet it cannot be denied that there was an element of self-interest in his espousal of the Czech cause – he stood to lose his business interests and an annual income of some £2,000 if the country broke up.[41]

Member of Parliament

Spears was twice a member of parliament (MP) – from 1922 to 1924 at Loughborough and from 1931 to 1945 at Carlisle. His pro-French views in the Commons earned him the nickname of 'the Member for Paris'.[42]

Loughborough

In December 1921, Spears was adopted at Loughborough as the parliamentary candidate for the National Liberal Party. He was elected unopposed in 1922 because the Labour candidate had failed to hand in his nomination papers in time, and the Conservatives had agreed not to put up a candidate to oppose him. With Winston Churchill in hospital and unable to campaign at Dundee, Spears and his wife took on the job, but Churchill was defeated. As a gesture of friendship, Spears offered to give up his seat at Loughborough – an offer which Churchill declined. His maiden speech, in February 1923, was critical of both the Foreign Office and the Embassy in Paris. He spoke out against the French occupation of the Ruhr in the House of Commons later the same month. In December, there was another election, with Spears retaining his seat as a National Liberal.[43] However, at the election in October 1924, he was beaten into third place by the Conservative and Labour candidates.[44] There followed two further attempts – both unsuccessful. The first was at a by-election at Bosworth in 1927, then at Carlisle at the General Election in June 1929.[45]

Carlisle

At the General Election in October 1931, Spears stood as a National Conservative candidate and was elected Member of Parliament for Carlisle.[46] In June 1935, Ramsay MacDonald resigned as Prime Minister of the National Government to be succeeded by the Conservative Stanley Baldwin. At the general election in November 1935, Spears again stood as a National Conservative candidate at Carlisle and was returned with a reduced majority.[47] At his house in 1934, there was held the first meeting of a cross-party group which would later become the European Study Group. Its members included Robert Boothby, Josiah Wedgwood, and Clement Attlee. Spears became its chairman in 1936; it would become a focus for those MPs who were suspicious of the European policies of Neville Chamberlain's National Government.[48]

First World War books

Liaison 1914; A Narrative of the Great Retreat, was published in September 1930 with a foreword by Winston Churchill. This personal account of his experiences as a liaison officer from July to September 1914 was well received.[49] The preface states: 'The object of this book is to contribute something to the true story of the war, and to vindicate the role of the British Expeditionary Force in 1914.'[50] As far as the French were concerned, Charles Lanrezac came in for heavy criticism but there was praise for Marshals Franchet d'Esperey and Joseph Joffre. On the British side, Spears wrote favourably of General Macdonough, who, as a colonel, had recruited him for military intelligence in 1909, and of Field Marshal Sir John French. Liaison 1914 describes vividly the horrors of war – the shoeless refugees, the loss of comrades and the devastated landscape. Two years later, a French translation was also successful, the only dissent coming from the son of General Lanrezac, who denied Spears' account of his father's rudeness to Sir John French. The French politician Paul Reynaud, who would later serve briefly as Prime Minister of France from 21 March to 16 June 1940, took the book as an illustration of how France must not allow herself to become separated from Britain. Liaison 1914 was published again in the US in May 1931 and received high praise.[51]

In 1939 Spears published Prelude to Victory, an account of the early months of 1917, containing a famous account of the Calais Conference in which Lloyd George had attempted to place the British forces under the command of General Nivelle, and culminating in the Battle of Arras. With war looming once again, Spears wrote that given time constraints he had chosen to concentrate on the period with the greatest lessons for Anglo-French relations. The book also contains a foreword by Winston Churchill, stating that Spears had not, in his view, been entirely fair to Lloyd George's wish to see Britain abstain from major offensives until the Americans were present in force.[52]

Opposes appeasement

Spears became a member of the so-called 'Eden Group' of anti-appeasement backbench MPs. This group, known disparagingly by the Conservative whips as 'The Glamour Boys', formed around Anthony Eden when he had resigned as Foreign Secretary in February 1938 in protest at the opening of negotiations with Italy by the Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain. Given his long-standing friendship with Winston Churchill, it was not surprising that Spears also joined the latter's group of anti-appeasers, known as 'The Old Guard'. Both groups called for rearmament in the face of Nazi threats.[53]

Eve of war

In August 1939, with war looming, Spears accompanied Winston Churchill to eastern France on a visit to the Maginot Line. In Strasbourg, he had the idea of floating mines linked together by cables down the Rhine – an action to be carried out on the declaration of war to damage bridges. Initially sceptical about the plan, Churchill would later approve it under the code name of Operation Royal Marine, but claim that it had been his own idea.[54]

Second World War

Phoney War

During the Phoney War, Spears favoured a hawkish policy; lamenting that Britain and France were not doing 'anything more warlike than dropping leaflets'. He urged active support for the Poles and wanted Germany to be bombed; he was set to speak in the House criticizing the failure to aid Poland as a violation of the Anglo-Polish Agreement but was dissuaded by Secretary of State for Air Kingsley Wood – much to his later regret.[55][56]

As Chairman of the Anglo-French Committee of the House of Commons, he fostered links with his friends across the Channel, and in October 1939 led a delegation of MPs on a visit to the Chamber of Deputies of France when they were taken to the Maginot Line.[57]

Four months later, Spears was sent to France to check on Operation Royal Marine for Winston Churchill, returning with him in April. Thousands of mines were to be released into the Rhine by the Royal Navy to destroy bridges and disrupt river traffic. The operation was vetoed by the French for fear of reprisals, but a postponement was finally agreed.[58]

On 10 May 1940, Operation Royal Marine was launched, producing the results that Spears had prophesied. However, by then the German blitzkrieg was underway and the success, as Churchill noted, was lost in the 'deluge of disaster' that was the fall of France.[59]

Churchill's Personal Representative to the French Prime Minister

Spears leaves for Paris

On 22 May 1940, Spears was summoned to 10 Downing Street. With British and French forces retreating before the German Blitzkrieg, and confused and contradictory reports arriving from across the Channel, Winston Churchill had decided to send Spears as his personal representative to Paul Reynaud, the Prime Minister of France, who was also acting as Minister of Defence. Three days later, having managed to find the various pieces of his uniform which he had not worn since leaving the army in 1919, he left by plane for Paris holding the rank of major general.[60]

Doubts about Pétain

During the chaos and confusion of the allied retreat, Spears continued to meet senior French political and military figures. He put forward the view that tanks could be halted by blowing up buildings; he also urged that prefects should not leave their departments without first ensuring that all petrol had been destroyed. On 26 May, he met Marshal Philippe Pétain; the old man reminisced about their time together during the First World War and 'treated him like a son'. Yet it seemed that the Marshal 'in his great age, epitomised the paralysis of the French people'. He became aware of the difficulties of re-creating a liaison organisation; in 1917 his mission had been established over several years. Starting again from scratch, the task seemed 'as impossible as to recall the dead'.[61]

Weygand's pessimism and Belgian capitulation

During a visit to London on Sunday 26 May, the French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud had reported to Churchill the view of the new Commander-in-Chief General Maxime Weygand that the struggle had become hopeless. On 27 May, Churchill demanded an immediate report from Spears, who was told to resist such defeatism. Reynaud referred to 'mortal danger' with reference to a possible attack by Fascist Italy, which had not yet entered the war; Spears' view was that the French army in the Alps was strong and that the only danger from the Italians would be if they interfered with the transport of troops from French North Africa. Yet perversely, Italian intervention might be good for allied morale: 'our combined fleets would whip them around the Mediterranean'. Reynaud and Spears argued, the former calling for more British air support, the latter, exasperated, asking, "Why don't you import Finns and Spaniards to show the people how to resist an invader?" [62] He went on to compare unfavourably the spirit of Paris in 1940 with that which he had known in 1914. That evening, Spears and the British Ambassador were summoned to the Ministry of War – news of the sudden Belgian surrender had infuriated Reynaud, Pétain and Weygand; Spears was briefly encouraged, but then irritated by Weygand's criticism of Lord Gort, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force. At the end of the day, Spears noted that he 'sensed a break in the relationship between the two nations; they were 'no longer one'.[63]

Invasion of Britain could be repulsed

On 28 May, Reynaud asked the British Ambassador, Sir Ronald Hugh Campbell and Spears for their view regarding a direct appeal for help to the United States. Sir Ronald declined to comment, but Spears said it had no chance of success; America would not declare war overnight and, in any case, it was not within the President's power. The prospect of an attempted German invasion across the Channel was of some comfort to Reynaud for it would give the French breathing space. Far from feeling intimidated, Spears welcomed the prospect: 'it did not even occur to me that we could not deal successfully with an attempted invasion. It would be wonderful indeed if the Nazi forces ventured on our own element, the sea'. During a discussion with Georges Mandel (Interior Minister, and one of the few hawks in the French Cabinet), he was told that Lebrun, the President of the Republic was weeping with despair. Mandel reported the criticism of Weygand and General Joseph Vuillemin (Commander of the French Armée de l'Air) over insufficient British air support; Vuillemin doubted that his own air force could withstand the losses it was sustaining.[64]

Discussions about Dunkirk, Narvik and Italy at Supreme War Council in Paris

On 31 May 1940, Churchill flew to Paris with Clement Attlee and Generals John Dill (Chief of the Imperial General Staff) and "Pug" Ismay for a meeting of the Anglo French Supreme War Council[65] to discuss the deteriorating military situation with a French delegation consisting of Reynaud, Pétain and Weygand. Three main points were considered: Narvik, the Dunkirk evacuation and the prospect of an Italian invasion of France. Spears did not take part in the discussions but was present 'taking voluminous notes'. It was agreed that British and French forces at Narvik be evacuated without delay – France urgently needed the manpower. Spears was impressed with the way that Churchill dominated the meeting. Dunkirk was the main topic, the French pointing out that 'out of 200,000 British 150,000 had been evacuated, whereas out of 200,000 Frenchmen only 15,000 had been taken off'. Churchill promised that now British and French soldiers would leave together 'bras dessus, bras dessous' – arm in arm. Italian entry into the war seemed imminent, with Churchill urging the bombing of the industrial north by British aircraft based in southern France while at the same time trying to gauge whether the French feared retaliation. Spears guessed that he was trying to assess the French will to fight. With the agenda completed, Churchill spoke passionately about the need for the two countries to fight on, or 'they would be reduced to the status of slaves for ever'. Spears was moved 'by the emotion that surged from Winston Churchill in great torrents'.[66]

During discussions after the meeting, a group formed around Churchill, Pétain and Spears. One of the French officials mentioned the possibility of France seeking a separate peace. Speaking to Pétain, Spears pointed out that such an event would provoke a blockade of France by Britain and the bombardment of all French ports in German hands. Churchill declared that Britain would fight on whatever happened.[67]

Returns to London with message for Churchill

On 7 June, with the Germans advancing on Paris, Spears flew to London in Churchill's personal aircraft bearing a personal message from Reynaud to the British Prime Minister. The French were requesting British divisions, and fighter squadrons to be based in France. In reply, Spears had inquired how many French troops were being transferred from North Africa. In London, he was asked whether the French would, as Clémenceau had said, "Fight outside Paris, inside Paris, behind Paris." His view was that they would not permit the destruction of that beautiful city, but this was contradicted on 11 June by a French government spokesman who told the Daily Telegraph that Paris would never be declared an open city. (The following day General Weygand issued orders declaring that the capital was not to be defended.)[68]

Accompanies Churchill to conference at Briare

On 11 June, Spears returned to France with Churchill, Eden, Generals Dill and Ismay and other staff officers. A meeting of the Anglo French Supreme War Council had been arranged with Reynaud, who had been forced to leave Paris, at Briare near Orleans, which was now the HQ of General Weygand. Also present was General Charles de Gaulle; Spears had not met him before and was impressed with his bearing. As wrangling continued over the level of support from Britain, Spears suddenly became aware that 'the battle of France was over and that no one believed in miracles'. The next day Weygand's catastrophic account of the military situation reinforced his pessimism. Despite assurances from Admiral François Darlan, the British were worried that the powerful French fleet might fall into German hands. With the conference drawing to a close, it dawned on Spears that the two countries were 'within sight of a cross-roads at which the destinies of the two nations might divide'.[69]

Spears argues with Pétain – departure for Tours

He remained at Briare after Churchill had left for London on 12 June; later that day he argued with Marshal Pétain, who maintained that an armistice with Germany was now inevitable, complaining that the British had left France to fight alone. Spears referred to Churchill's words of defiance at the meeting, feeling that some of the French might remain in the struggle if they could be made to believe that Britain would fight on. The Marshal replied, "You cannot beat Hitler with words." He began to feel estrangement from Pétain, whose attitude, for the first time in their relationship, savoured of hostility. His concern was now to link up with the Ambassador, Sir Ronald Hugh Campbell, and he set out by car for Tours. On the way they drove through crowds of refugees, many of whom had become stranded when their cars ran out of fuel. At the Chateau de Chissey high above the River Cher, he found Reynaud and his ministers struggling to govern France, but with insufficient telephone lines and in makeshift accommodation. Again he met de Gaulle, 'whose courage was keen and clear, born of love of, and inspired by, his country'. Later in the day, he heard to his astonishment that Reynaud had left for Tours because Churchill was flying over for another meeting. In the confusion, neither Spears nor Sir Ronald had been informed. Fearful that he might not arrive in time, he set off at once along roads choked with refugees.[70]

Last-ditch talks at Tours

What would prove to be the final meeting of the Anglo French Supreme War Council took place at the Préfecture in Tours on 13 June. When Spears arrived, the British delegation – Churchill, Lord Halifax, Lord Beaverbrook, Sir Alexander Cadogan and General 'Pug' Ismay – were already there. The French Prime Minister, Paul Reynaud, was accompanied by Paul Baudoin, a member of the War Committee. Spears found the atmosphere quite different from that at Briare, where Churchill had expressed good will, sympathy and sorrow; now it was like a business meeting, with the British keenly appraising the situation from its own point of view. Reynaud declared that unless immediate help was assured by the US, the French government would have to give up the struggle. He acknowledged that the two countries had agreed never to conclude a separate peace[71] – but France was physically incapable of carrying on. The news was received by the British with shock and horror; Spears' feelings were expressed by the exclamation marks which he scrawled in his notes. Spears noted Churchill's determination as he said, "We must fight, we will fight, and that is why we must ask our friends to fight on." Prime Minister Reynaud acknowledged that Britain would continue the war, affirming that France would also continue the struggle from North Africa, if necessary – but only if there were a chance of success. That success could come only if America were prepared to join the fray. The French leader called for British understanding, asking again for France to be released from her obligation not to conclude a separate peace now that she could do no more. Spears passed a note to Churchill proposing an adjournment – a suggestion that was taken up.[72]

The British walked around the sodden garden of the prefecture, Spears reporting that Reynaud's mood had changed since that morning, when he had spoken of his resistance to the 'armisticers'. He told Churchill that he was certain that de Gaulle was staunch, but that General Weygand looked upon anyone who wished to fight as an enemy. Beaverbrook urged Churchill to repeat what he had already said – namely that U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt be telegraphed and American help sought. When the proceedings were resumed, it was agreed that both countries would send identical telegrams. It was on this note that the conference ended.[73]

Linguistic misunderstanding

After the meeting, de Gaulle told Spears that Paul Baudoin had been telling journalists that Churchill had said that "he would understand if France concluded a separate armistice" ... "que l'Angleterre comprendrait si la France faisait un armistice et une paix séparée". Spears realised there had been a linguistic misunderstanding. When Reynaud spoke (in French) about a separate armistice, Churchill had said, "Je comprends" (I understand) in the sense of 'I understand what you say', not in the sense of 'I agree'. Just as Churchill was about to take off for Britain, Spears obtained his assurance that he had never given consent to a separate armistice. But the damage had been done and, on 23 June, the words would be quoted by Admiral François Darlan, who signalled all French warships saying that the British Prime Minister had declared that 'he understood' the necessity for France to bring the struggle to an end'.[75]

Churchill fails to address French cabinet

The day ended in confusion – Churchill flew back to London without speaking to the French cabinet, as had been promised by Reynaud. The ministers were dismayed and angry; Spears was depressed, realising that 'an opportunity that might not recur had been missed'. He was at a loss to understand why a meeting had not taken place – had Reynaud simply forgotten? Did Reynaud wish to explain the situation to the ministers himself? In any event, his ministers were disillusioned and felt abandoned. Spears believed that this event played its part in swaying the majority of the cabinet towards surrender. He was sure that 'by the night of 13 June, the possibility of France remaining in the war had almost disappeared'. The only hope rested on the decision of President Roosevelt – would America now join the war?[76]

End game at Bordeaux – London offers a Franco-British Union

On 14 June, Spears left Tours to look for Reynaud and his government, which had moved to Bordeaux. On the way, he was conscious that the attitude of people to the sight of a British uniform had changed – they were morose if not hostile. When he reached Bordeaux, he learnt that Paris had fallen that morning. Spears found Reynaud – he had not received a satisfactory reply from Washington but was still clinging to the hope. Spears found him worn out, forlorn and undecided. The British consulate was besieged with crowds of would-be refugees seeking passage out of France.[77]

Spears rails against defeatism

The next day he clashed with Camille Chautemps, Vice-President of the cabinet, upbraiding him for his defeatism and praising the spirit of the French soldiers that he had known during the First World War. He later spoke to Roland de Margerie, Reynaud's Chef de cabinet and raised the matter of several hundred German pilots who were prisoners of the French, asking that they be handed over to the British. However, there was much confusion and telephone communications were difficult even within the city of Bordeaux itself. Spears now had misgivings about Reynaud's determination to stay in the war, if necessary from French North Africa. He was outraged that despite the critical situation, the French Commander in Chief in North Africa was opposed to receiving troops from France. There was insufficient accommodation, no spare weapons, there was a shortage of doctors; moreover the climate was rather warm for young Frenchmen at this season! In Spears' view this was monstrous; why did Reynaud not dismiss the obstructionist general? He asked why the idea of forming a redoubt in Brittany had been dropped and why Reynaud did not dismiss General Weygand for his defeatism. Margerie replied that the people had faith in Weygand and that he also had the support of Pétain. Continuing in the same vein, Spears poured cold water on the notion that America might join the war. Spears and the ambassador sent a telegram to London explaining that everything now hung on an assurance from the US, adding that they would to their utmost to obtain the scuttling of the French fleet. Their final words were, "We have little confidence in anything now." They heard that Marshal Pétain would resign if American help was not forthcoming; Spears concluded that Reynaud would not continue in the face of combined opposition from the Marshal and Weygand. He longed for the presence of Churchill, which would have been 'worth more than millions in gold could buy'.[78]

Spears and the Ambassador were called following a meeting of the cabinet. The linguistic confusion from Tours returned to haunt them as Reynaud began, "As Mr Churchill stated at Tours he would agree that France should sue for an armistice...." Spears stopped writing and objected, "I cannot take that down for it is untrue." The minutes of the Tours meeting were produced and Spears was vindicated. Reynaud wrote a message to Churchill, stating that France sought leave of Britain to inquire about armistice terms; if Britain declined, he would resign. At this point an aide handed him Roosevelt's refusal to declare war – Reynaud was in despair. He did, however, guarantee that any successor would not surrender the fleet in an armistice. Spears felt sympathy for the French army, but contempt for Weygand, 'a hysterical, egocentric old man'.[79]

British refusal to allow France to seek a separate peace

By 16 June, Spears and Sir Ronald Campbell were sure that once the French had asked for an armistice they would never fight again. With regard to the French Empire and the fleet, there was a possibility that if German armistice terms were too harsh, the Empire might rebel against them, even if metropolitan France succumbed. It did not occur to them that Hitler would split France into two zones thus dividing it against itself. Early the same morning, Reynaud, nervously exhausted and depressed, asked again for France to be relieved of its undertaking not to make a separate peace. The British took a hard line, pointing out that the solemn undertaking had been drawn up to meet the existing contingency; in any case, France [with its overseas possessions and fleet] was still in a position to carry on. While these top-level discussions were being held, Hélène de Portes, Reynaud's mistress repeatedly entered the room, much to the irritation of Spears and the Ambassador. Spears felt that her pernicious influence had done Reynaud great harm.[80][81]

British acceptance of armistice dependent on fate of French fleet

Shortly before lunch a telegram arrived from London agreeing that France could seek armistice terms provided that the French fleet was sailed forthwith for British harbours pending negotiations. Spears and the Ambassador felt this would be taken as an insult by the French Navy and an indication of distrust. Reynaud received the news with derision – if Britain wanted France to continue the war from North Africa, how could they ask her fleet to go to British harbours? He had spoken by telephone with Churchill and asked Spears to arrange a meeting with the British Prime Minister, at sea somewhere off Brittany. The meeting, however, never took place as he preferred to go in a French warship and this never materialised. As the day wore on, Spears became more aware of defeatism – but the hard-liners tended to be socialists. His British uniform struck a false note and people avoided him.[82]

French reject Franco-British Union

On the afternoon of 16 June, Spears and the Ambassador met Reynaud to convey a message from London – it would be in the interest of both countries for the French fleet to be moved to British ports; it was assumed that every effort would be made to transfer the air force to North Africa or to Britain; Polish, Belgian and Czech troops in France should be sent to North Africa. While they were arguing with increasing acrimony about the fleet, a call came through from de Gaulle, who was in London. The British proposition was nothing less than a Declaration of Union – 'France and Great Britain shall no longer be two nations, but one Franco-British Union. Every citizen of France will enjoy immediate citizenship of Great Britain; every British subject will become a citizen of France.' Spears became 'transfixed with amazement'; Reynaud was exulted. When the news got out, hard-liners such as Georges Mandel were pleased and relieved. The proposal would be put before the French cabinet. Spears was optimistic that it would be accepted for how could it be that of the countries fighting Germany, France should be the only one to give up the struggle, when she possessed an Empire second only to our own and a fleet whole and entire, the strongest after ours in Europe'. Yet he joked that the only common denominator of an Anglo-French Parliament would be 'an abysmal ignorance of each other's language'![83]

While the cabinet meeting was taking place, Spears and the Ambassador heard that Churchill, Clement Attlee, Sir Archibald Sinclair, the three Chiefs of Staff and others would arrive off Brittany in a warship the next day at noon for talks with the French. However, the French cabinet rejected the offer of union; Reynaud would be resigning. One minister had commented that the proposal would make France into a British Dominion. Spears, on the other hand, felt the rejection 'was like stabbing a friend bent over you in grief and affection'. Churchill and his delegation were already in the train at Waterloo station, when news of the rejection came through. He returned to Downing Street 'with a heavy heart'.[84]

De Gaulle fears arrest

In Bordeaux, Spears and Sir Ronald Campbell went to see Reynaud at his dimly-lit offices. According to Spears, he was approached in the darkness by de Gaulle, who said that Weygand intended to arrest him. Reynaud told the British that Pétain would be forming a government. Spears noted that it would consist entirely of defeatists and that the French Prime Minister had 'the air of a man relieved of a great burden'. Incredibly Reynaud asked when Churchill would be arriving off Brittany in the morning. Spears was short with him: "Tomorrow there will be a new government and you will no longer speak for anyone." However, he later came to realise that Reynaud had never double-crossed his ally, but had done his best to hold the alliance while fighting against men stronger than he was. His fault lay in his inability to pick good men. After the meeting, Spears found de Gaulle and decided to help him escape to Britain. He telephoned Churchill and got his somewhat reluctant agreement to bring over both de Gaulle and Georges Mandel. The latter, however, declined to come, opting instead to go to North Africa. It was arranged that de Gaulle would come to Spears' hotel at 7 o'clock in the morning of the following day.[85][86]

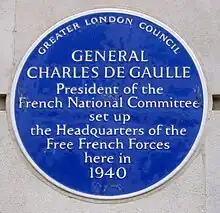

Spears leaves for Britain with de Gaulle

On 17 June, de Gaulle and his ADC, Lieutenant Geoffroy de Courcel,[87] went with Spears to the airfield on the pretext of seeing him off. After a delay while de Gaulle's baggage was secured, the De Havilland Flamingo took off for Britain. Winston Churchill wrote that Spears personally rescued de Gaulle from France just before the German conquest, literally pulling the Frenchman into his plane as it was taking off from Bordeaux for Britain.[88][89] When they had reached Britain, de Gaulle gave Spears a signed photograph with the inscription, "To General Spears, witness, ally, friend."[90]

Spears heads British government's mission to de Gaulle

De Gaulle's famous Appeal of 18 June was transmitted in French by the BBC and repeated on 22 June, the text having then been translated into English for the benefit of 10 Downing Street by Nancy Maurice, Spears's secretary. Towards the end of June 1940, Spears was appointed head of the British government's mission to de Gaulle,[91] whose headquarters were finally established at 4 Carlton Gardens in London.[92]

Aftermath of Dunkirk and Mers el Kebir

Over 100,000 French troops were evacuated from Dunkirk during Operation Dynamo between 26 May and 4 June 1940, but the majority returned to France from ports in the west of England within a few days.[93] On 3 July, Spears had the unpleasant task of informing de Gaulle of the British ultimatum to the French ships at anchor in the North African port of Mers El Kébir; this would result in the first phase of Operation Catapult, an action which led to the loss many French warships and the deaths of 1,297 French seamen. The attack caused great hostility towards Britain and made it even more difficult for de Gaulle to recruit men to his cause. De Gaulle, while regarding the naval action as 'inevitable', was initially uncertain whether he could still collaborate with Britain. Spears tried to encourage him and at the end of July in an unsuccessful attempt to rally support, flew to the internment camp at Aintree Racecourse near Liverpool, where French seamen who had been in British ports were taken as part of Operation Catapult.[94] In the event, de Gaulle had only some 1,300 men at his disposal in Britain, the majority being those who had recently been evacuated from Narvik following the Norwegian Campaign.[95]

Dakar – Operation Menace

Winston Churchill pressed for action by the Free French to turn French colonies from the Vichy regime. The target was Dakar in French West Africa; the main reason being that it could become a base threatening shipping in the Atlantic. A show of force by the Royal Navy was planned coupled with a landing by de Gaulle's which, it was hoped, would convince the Vichy defenders to defect. Spears accompanied de Gaulle on the mission, (Operation Menace), with orders to report directly to the Prime Minister. However, security had been lax and the destination was said to be common talk among French troops in London.[96]

While the task force was en route, it came in sight of a French fleet – including three cruisers – on its way from Toulon to Douala to recapture French Equatorial Africa which had declared for de Gaulle. Surprised, the French fleet sailed for Dakar instead, thus making the outcome of the expedition much more uncertain.[97] Churchill was now of the opinion that the project should be abandoned, but de Gaulle insisted and a telegram from Spears to the Prime Minister stated, "I wish to insist to you personally and formally that the plan for the constitution of French Africa through Dakar should be upheld and carried out."[98]

On 23 September 1940, a landing by de Gaulle's troops was repulsed and, in the ensuing naval engagement, two British capital ships and two cruisers were damaged while the Vichy French lost two destroyers and a submarine. Finally Churchill ordered the operation to be called off. The Free French had been snubbed by their countrymen; de Gaulle and Spears were deeply depressed, the latter fearing for his own reputation – and rightly so. The Daily Mirror wrote: “Dakar has claims to rank with the lowest depths of imbecility to which we have yet sunk.” De Gaulle was further discredited with the Americans and began to criticise Spears openly, telling Churchill that he was 'intelligent but egotistical and hampering because of his unpopularity at the War Office etc.'.[99] John Colville, Churchill's private secretary, wrote on 27 October 1940, “It is true that Spears' emphatic telegrams persuaded the Cabinet to revert to the Dakar scheme after it had, on the advice of the Chiefs of Staff, been abandoned.” [100]

De Gaulle and Spears in the Levant

.svg.png.webp)

Still acting as Churchill's personal representative to the Free French, Spears left England with de Gaulle for the Levant via Cairo in March 1941. They were received by British officers, including General Archibald Wavell, the British Commander in Chief Middle East, and also General Georges Catroux, the former Governor General of French Indo-China, who had been relieved of his post by the Vichy France regime of Marshal Philippe Pétain.[101]

Wavell, the British Commander-in-Chief, wanted to negotiate with the Governor of French Somaliland, which was still loyal to Vichy France, and lift the blockade of that territory in exchange for the right to send supplies to British forces in Abyssinia via the railway from the coast to Addis Ababa. However, de Gaulle and Spears argued in favour of firmness, the former arguing that a detachment of his Free French should be sent to confront the Vichy Armistice Army troops in the hope that the latter would be persuaded to change sides. Wavell agreed, but was later overruled by Anthony Eden, who feared an open clash between the two French factions. British vacillations persisted against the advice of Spears and to the extreme irritation of de Gaulle.[102]

Syria and Lebanon

More serious differences between Britain and de Gaulle soon emerged over Syria and Lebanon. De Gaulle and Spears held that it was essential to deny the Germans access to Vichy French Air Force bases in Syria from where they would threaten the Suez Canal. However, Wavell was reluctant to stretch his limited forces and did not want to risk a clash with the French in Syria.[103]

The French in Syria had initially been in favour of continuing the struggle against Germany but had been snubbed by Wavell, who declined the offer of cooperation from three French divisions. By the time de Gaulle reached the Levant, Vichy had replaced any Frenchmen who were sympathetic towards Britain.[104]

Having left the Middle East with de Gaulle on a visit to French Equatorial Africa, Spears had his first major row with the general who, in a fit of pique caused by 'some quite minor action by the British government', suddenly declared that the landing ground at Fort Lamy would no longer be available to British aircraft transiting Africa. Spears countered furiously by threatening to summon up British troops to take over the aerodrome and the matter blew over.[105]

De Gaulle told Spears that the Vichy authorities in the Middle East were acting against the Free French and the British. French ships blockaded by the British at Alexandria were permitted to transmit coded messages which were anything but helpful to the British cause. Their crews were allowed to take leave in the Levant States where they stoked up anti-British feeling. They also brought back information about British naval and troop movements which would find its way back to Vichy. In Fulfilment of a Mission Spears writes bitterly about how Britain was providing pay for Vichy sailors who were allowed to remit money back to France. Their pay would, of course, be forfeited if they joined de Gaulle. However, his biggest bone of contention – one over which he frequently clashed with the Foreign Office and the Admiralty – was that a French ship, SS Providence, was allowed to sail unchallenged between Beirut and Marseille. It carried contraband 'and a living cargo of French soldiers and officials [prisoners] who were well disposed to us or who wished to continue the fight at our side'.[106]

De Gaulle and Spears held the view that the British at GHQ in Cairo were unwilling to accept that they had been duped over the level of collaboration between Germany and the Vichy-controlled states in the Levant. The British military authorities feared that a blockade of the Levant would cause hardship and thus antagonise the civilian population. However, Spears pointed out that the Vichy French were already unpopular with the local population – ordinary people resented being lorded over by defeated foreigners. He urged aggressive propaganda aimed at the Vichy French in support of the Free French and British policy. He felt that the Free French would be considered as something different as they were allies of Britain and enjoyed the dignity of fighting their enemy instead of submitting to him.[107]

On 13 May 1941, the fears of de Gaulle and Spears were realised when German aircraft landed in Syria in support of the Iraqi rebel Rashid Ali, who was opposed to the pro-British Kingdom of Iraq. On 8 June, 30,000 troops (Indian Army, British, Australian, Free French and the Trans-Jordanian Frontier Force) invaded Lebanon and Syria in what was known as Operation Exporter. There was stiff resistance from the Vichy French and Spears commented bitterly on 'that strange class of Frenchmen who had developed a vigour in defeat which had not been apparent when they were defending their country'.[108]

Spears soon became aware of the poor liaison which existed between the British Embassy in Cairo, the armed forces, Palestine and the Sudan. The arrival in Cairo in July 1941 of Oliver Lyttelton, who was a Minister of State and a member of the War Cabinet, improved matters considerably. The Middle East Defence Council was also formed – a body that Spears would later join.[109]

In January 1942, having received the title of KBE, Spears was appointed the first British minister to Syria and Lebanon. Beirut still holds his name on one of its major streets, Rue Spears.[110]

Later life

Spears lost his parliamentary seat in the 1945 General Election, which saw the Conservative Party defeated in a landslide. The same year he accepted the position of chairman of the commercial firm Ashanti Goldfields. From 1948 to 1966 he was chairman of the Institute of Directors, frequently visiting West Africa. Spears published several books during the post-war period: Assignment to Catastrophe (1954);. Two Men who Saved France (1966), and his own autobiography, The Picnic Basket (1967).

In 1947 he founded the Anglo-Arab Association.[111][112]

Spears was created a baronet, of Warfield, Berkshire, on 30 June 1953. He died on 27 January 1974 at the age of 87 at the Heatherwood Hospital at Ascot.[110] A memorial service at St. Margaret's, Westminster followed on 7 March. The trumpeters of the 11th Hussars sounded a fanfare; the French and Lebanese ambassadors were in attendance. General Sir Edward Louis Spears lies buried at Warfield alongside the graves of his first wife, May, and his son, Michael.[113]

Tragedy of his life

In the foreword to Fulfilment of a Mission, the account by Spears of his service in the Levant, John Terraine, writes of 'the tragedy of his life'. By this he meant that someone who should have been a warm friend of de Gaulle had become an intractable and spiteful enemy. His boyhood had been spent in France. He was happy in France, he liked the spirit of the people. He liked the sailors of Brittany and the peasants of Burgundy. He understood their wit. It amused him to talk to them and to be with them. It had been a very bitter experience to find himself opposed and having to oppose French policy so often. That, he said, had been the tragedy of his life. Terraine comments further, "If Mr Graham Greene had not already made good use of it, the title of Fulfilment of a Mission might just as well have been, The End of an Affair."[114]

Linguistic competence

In October 1939, he led a delegation of British MPs to France and spoke on French Radio. After the broadcast, listeners protested that his speech had been read for him because 'an Englishman without an accent did not exist'![115] In February 1940, he gave a lecture on the British war effort to a large and distinguished audience in Paris. Fluent though he was, he nevertheless felt it would be helpful to attend lessons with an elocution teacher who coached leading French actors.[116] It must be supposed that he also spoke some German thanks to the two years which he had spent at a boarding school in Germany.[117]

Despite his linguistic competence, Spears hated interpreting. He realised that it required qualifications beyond a mere knowledge of two languages. At the conference at Tours on 13 June 1940, he had the awesome responsibility of translating Paul Reynaud's French into English and Winston Churchill's English into French. The final phase of the Battle of France and the destiny of two nations were at stake; it promised to be the gravest of the meetings so far held between the two governments. Furthermore, he was aware that others in the room were completely conversant with both languages and that most of them would have thought of the word that he was searching for before he had found it.[118]

Media

Sir Edward Spears appears as an interviewee in numerous episodes of the 1964 documentary series The Great War, especially in reference to the major roles he played as liaison to the French Fifth Army in the episodes Our hats we doff to General Joffre, detailing the Great Retreat to the Marne and This business may last a long time, detailing the First Battle of the Marne and the subsequent Race to the Sea. He appeared in the 1969 French-West German documentary The Sorrow and the Pity about collaboration in Vichy France. He also appeared near the end of his life, in the episode "France Falls" of the landmark 1974 documentary series, The World at War.

Notes and sources

- ↑ Egremont, Max (1997). Under Two Flags. London: Phoenix – Orion Books. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-7538-0147-7.

- ↑ Spiers, Alexander (2006). General English and French Dictionary (Google Book Search). Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 2, 82.

- ↑ Julian Jackson, The Fall of France, Oxford 2003, 91.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 4, 6.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 6–22.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 23.

- ↑ "Battlefield Colloquialisms of the Great War (WW1) by Paul Hinckley". Archived from the original on 14 April 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 41.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 6, 22, 41, 43.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 23, 25, 30.

- ↑ "Telephones, Telegraphs and Automobiles: The Response of British Commanders to New Communications Technologies in 1914 by Nikolas Gardner" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2004. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 28–29, 34.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 38–40.

- 1 2 Egremont, p. 81.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 42, 50.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 43, 48, 49.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 48.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 55.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 56–58.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 59.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 66.

- ↑ "Portrait – Georges Clémenceau (1841–1929)". Archived from the original on 11 June 2004. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 68–69, 73.

- ↑ "Culture.fr – le portail de la culture". Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 77–80.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 9–10, 39–40, 46.

- ↑ Borden, Mary (1946). Journey down a Blind Alley. London: Hutchinson & Co. p. 122.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 62, 77.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 95, 128–129, 236–237, 289–291, 304.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 118.

- ↑ Borden, pp. 13, 116–117, inside front cover.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin (1995). The Day the War Ended. London: HarperCollins. p. 397. ISBN 0-00-711622-5.

- ↑ Borden, pp. 295–296.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 91–93, 113, 237, 305, 316.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 98.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 136–7.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 139–141.

- ↑ Berthon, Simon (2001). Allies at War. London: HarperCollins. p. 80. ISBN 0-00-711622-5.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 100–106, 111.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 113.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 114.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 124.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 133.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 127.

- ↑ ”A spirited, colourful and brilliantly written memoir of war, fascinating in its richness of detail, this is by far the most interesting book in English on the opening campaign in France. When the author’s personal predudices become involved, he exercises a certain freedom in manipulating the facts.” Tuchman, Barbara (1962) August 1914, 1962 edition published by Constable and Co, 1980 p.b. edition, Macmillan Press, ISBN 0-333-30516-7 p.434

- ↑ Liaison 1914, Author's Preface to the First Edition, Cassell 1999, xxxi.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 24, 119–120, 123, 125.

- ↑ Spears 1939, pp. 11, 15.

- ↑ "Oxford DNB". Oxford University Press. 2006. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ↑ Spears, Sir Edward (1954). Prelude to Dunkirk. London: Heinemann. p. 10.

- ↑ Bouverie, Tim (2019). Appeasement: Chamberlain, Hitler, Churchill, and the Road to War (1 ed.). New York: Tim Duggan Books. pp. 380-381. ISBN 978-0-451-49984-4. OCLC 1042099346.

- ↑ Prelude to Dunkirk – Spears, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Prelude to Dunkirk – Spears, p. 38.

- ↑ Prelude to Dunkirk – Spears, pp. 96–99, 73, 101.

- ↑ "Rear-Admiral Roger Wellby (obituary)". The Daily Telegraph. 3 December 2003. Archived from the original on 23 January 2004. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ↑ Prelude to Dunkirk – Spears, pp. 153–154, 176.

- ↑ Prelude to Dunkirk – Spears, pp. 219, 224, 234.

- ↑ A reference to the spirited resistance of Finland to the Russian invasion of November 1939 in the Winter War, and that of the Spanish guerrillas to Napoleon.

- ↑ Prelude to Dunkirk – Spears, pp. 237–239, 244–251.

- ↑ Prelude to Dunkirk – Spears, pp. 253, 261–263.

- ↑ Jackson, Julian (2004). The Fall of France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-19-280550-8.

- ↑ Prelude to Dunkirk – Spears, pp. 253, 292–314.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 170.

- ↑ Spears, Sir Edward (1954). The Fall of France. London: Heinemann. pp. 110–123, 148.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 137–171.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 172–197.

- ↑ At a meeting of the Anglo French Supreme War Council held in London on 28 March 1940.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 199–213.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 214–218.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 310–302.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 218–220.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 221–234.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 235–253.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 246–263.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 263–275.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 276–280.

- ↑ In his diary for 4 March 1941, Harold Nicolson recalls having dinner with Spears at the Ritz in London. Spears had said that de Portes was passionately anti-British; she believed that Reynaud would become dictator of France and that she would be the power behind the throne. She felt that our democratic ideas would prevent this pattern of state government. She surrounded Reynaud with fifth-columnists and spies. Spears further thought that Reynaud had an inferiority complex due to his small stature; La Comtesse de Portes made him feel tall, grand and powerful. Anyone who urged resistance would be shouted at: 'C'est moi qui suis la maîtresse ici!' Towards the end of June, after Reynaud had resigned, they were in their car when Reynaud ran into a tree. A suitcase hit her on the back of the neck and she was killed instantly.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 282–288.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 290–294.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 296–300.

- ↑ Egremont (p. 191) notes that Mandel went to North Africa but was sent back to France, where he was murdered in 1944.

- ↑ The Fall of France, pp. 235–318.

- ↑ See French Wikipedia at fr:Geoffroy Chodron de Courcel.

- ↑ Winston S. Churchill (1949). Their Finest Hour. Houghton Mifflin.

- ↑ However, Egremont (p.190) notes that Spears' account of the dramatic rescue was contested after the war – by Gaullists in particular. His part was played down in France, with some accounts suggesting that he had fled fearing for his life because he was Jewish. In Charles de Gaulle by Eric Roussel (Gaillimard, 2002, p.121), Geoffroy de Courcel is scornful of Spears' description of how he had jumped aboard the taxiing aircraft: 'Courcel, more nimble, was in a trice'. De Courcel comments that this action attributes to him an acrobatic prowess which would, even at that time, have been well beyond his capability. 'C'est m'attribuer des dons acrobatiques dont, même à l'époque, j'aurais été bien incapable.'

- ↑ Berthon, p. 80.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 195–196.

- ↑ London Calling, École supérieure de journalisme de Lille, archived from the original on 20 November 2008, retrieved 22 October 2008

- ↑ "Le Paradis apres l'Enfer: the French Soldiers Evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940 – Dissertation by Rhiannon Looseley". Franco British Council. 2005. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 197–200.

- ↑ "Les Français libres" (PDF). Fondation de la France Libre. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 201–204.

- ↑ Jean Lacouture, De Gaulle, Seuil, 2010 (1984) vol 1, pp. 437–438.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 206–207.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 214, 216.

- ↑ Colville, John (1985). The Fringes of Power – 10 Downing Street Diaries 1939–1955. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 277. ISBN 0-393-02223-4.

- ↑ Spears, Sir Edward (1977). Fulfilment of a Mission. London: Leo Cooper. p. 6. ISBN 0-85052-234-X.

- ↑ Fulfilment of a Mission – Spears, pp. 11–13.

- ↑ Fulfilment of a Mission – Spears, pp. 61–64.

- ↑ Fulfilment of a Mission – Spears, pp. 15, 25.

- ↑ Fulfilment of a Mission – Spears, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Fulfilment of a Mission – Spears, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Fulfilment of a Mission – Spears, pp. 26, 33.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 225–226.

- ↑ Egremont, pp. 21, 111.

- 1 2 "Spears, Sir Edward Louis, baronet (1886–1974)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online January 2008 ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ↑ "The Discovery Service".

- ↑ Middle East International No 569, 27 February 1998; James Craig p.23. Review of “Under Two Flags”/Egremont.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 316.

- ↑ Fulfilment of a Mission – Spears, p. ix.

- ↑ Prelude to Dunkirk – Spears, p. 46.

- ↑ Prelude to Dunkirk – Spears, p. 72.

- ↑ Egremont, p. 6.

- ↑ The Fall of France – Spears, pp. 201–202.

References

- Berthon, Simon (2001). Allies at War. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-711622-5.

- Borden, Mary (1946). Journey down a Blind Alley. London: Hutchinson & Co.

- Churchill, Winston S. (1949). Their Finest Hour. Houghton Mifflin.

- Colville, John (1985). The Fringes of Power – 10 Downing Street Diaries 1939–1955. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-393-02223-4.

- Egremont, Max (1997). Under Two Flags: The Life of Major General Sir Edward Spears. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-2978-1347-7.

- Gilbert, Martin (1995). The Day the War Ended. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-255597-2.

- Nicolson, Harold (1967). Diaries and Letters, 1939–1945. London: Collins.

- Spears, Sir Edward (1999) [1930]. Liaison 1914. London: Eyre & Spottiswood. ISBN 0-304-35228-4.

- Spears, Sir Edward (1939). Prelude to Victory (online ed.). London: Jonathan Cape. OCLC 459267081. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- Spears, Sir Edward (1954). Prelude to Dunkirk (Part 1 of Assignment to Catastrophe). London: Heinemann.

- Spears, Sir Edward (1954). The Fall of France (Part 2 of Assignment to Catastrophe). London: Heinemann.

- Spears, Sir Edward (1977). Fulfilment of a Mission. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 0-85052-234-X.