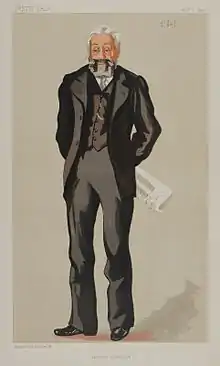

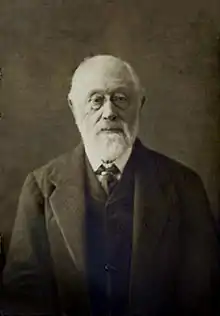

Sir Philip Magnus, 1st Baronet (7 October 1842 – 29 August 1933) was an English educational reformer, rabbi, and politician, who represented the London University constituency as a Unionist Member of Parliament from 1906 to 1922. He had previously been appointed director of the City and Guilds of London Institute, from where he helped oversee the creation of a modern system of technical education in the United Kingdom. He was married to the writer and teacher Katie Magnus, and was father of the publisher Laurie Magnus. Laurie predeceased him, and on his own death in 1933 he was succeeded in the baronetcy by Laurie's eldest son Philip.

Biography

After studying at University College School and University College London, where he took first-class honours in both arts and science, Magnus chose to take up a religious career. An active member of the Reform Judaism movement in Britain, he spent three years studying at the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums in Berlin and returned to London to take up a post as assistant rabbi at the West London Synagogue in 1866.[1]

During his time as rabbi, Magnus supplemented his income by teaching private students, which grew steadily into a regular occupation. He held a lectureship at Stockwell teacher training college, taught at University College London, and examined prospective teachers for the College of Preceptors. In 1880, he finally left his rabbinical work to become director of the newly formed City and Guilds of London Institute. He oversaw the rapid growth of the institute, focusing his attentions on the technical education departments, of which he became Superintendent in 1888; he would hold this post until retiring in 1915.[2]

Outside of the institute, Magnus was influential in setting national education policy; he sat on the Samuelson Commission (the Royal Commission on Technical Instruction) of 1884, and for his work here was knighted in 1886.[1] The commission's report led to the Technical Instruction Act 1889, which supported local authorities in creating technical schools around the country.[3] He encouraged the reform of primary and secondary state education in London, and helped oversee the merger of the City and Guilds Institute into the newly formed Imperial College of Science and Technology.[1]

In the 1906 general election, he was elected to Parliament as a Liberal Unionist, representing the London University constituency.[1] He narrowly defeated Sir Michael Foster, a prominent Cambridge physiologist, by twenty-four votes. Foster was a Liberal, who on his initial election had joined the Liberal Unionists and supported Salisbury's Conservative government; however, he later crossed the floor to rejoin the Liberals, in large part due to his opposition to the 1902 educational reforms.[4] Magnus was re-elected in 1910, after which, in 1912, the Liberal Unionists merged with the Conservatives to form the Unionist Party. He held the seat in 1918 – where he defeated Sidney Webb – but did not seek re-election in 1922.[1]

In retirement, he continued to sit as a member of the Senate of the University of London, and chaired the council of the Royal Society of Arts. He was a governor of the Northampton Institute and Royal Grammar School, Guildford, and a vice-president of the Anglo-Jewish Association, the Board of Deputies of British Jews, and Jews' College.[2] In 1917, he co-founded the anti-Zionist League of British Jews.[5]

He died in 1933 and is buried at Golders Green Jewish Cemetery.

Arms

|

|

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bailey (2004)

- 1 2 Bailey (2004); Who Was Who

- ↑ "Technical colleges and further education: Science and Art Department". The National Archives (UK). Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ Romano (2004)

- ↑ "To Combat Zionism". The Modern View. 28 December 1917. p. 13. Retrieved 17 April 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Burke's Peerage. 1956.

Sources

- Bailey, Bill (2004). "Magnus, Sir Philip, first baronet (1842–1933)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40870. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Kadish, Sharman (2004). "Magnus [née Emanuel], Katie, Lady Magnus (1844–1924)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/55630. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Matthew, H.C.G. (2004). "Magnus [later Magnus-Allcroft], Sir Philip Montefiore, second baronet (1906–1988)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/60712. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Romano, Terrie M. (2004). "Foster, Sir Michael (1836–1907)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33218. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Magnus, Sir Philip". Who's Who & Who Was Who. Vol. 1920–2008. A & C Black. Retrieved 23 February 2013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

- Foden, Frank (1970). Philip Magnus: Victorian educational pioneer. London: Vallentine Mitchell. ISBN 0853030448.