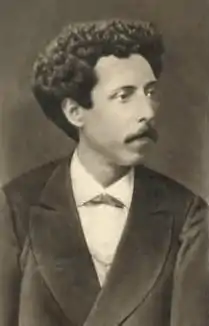

José Tomás de Sousa Martins | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 March 1843 |

| Died | 18 August 1897 (aged 54) |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Occupation(s) | Doctor and professor |

José Tomás de Sousa Martins (7 March 1843 – 18 August 1897) was a doctor renowned for his work for the poor in Lisbon, Portugal. After his death, a secular cult arose around his personality in which he is thanked for "miraculous" cures.

Biography

Early life

Sousa Martins was born in Alhandra (near Vila Franca de Xira) on 7 March 1843, the son of Caetano Martins, a carpenter, and Maria das Dores de Sousa Martins. The household was a poor one, and became poorer still after Caetano's death in 1851, when José was seven years old. He spent his childhood and completed his primary education in Alhandra. At the age of 12, his mother advised him to leave for Lisbon where his maternal uncle, Lázaro Joaquim de Sousa Pereira, had established himself as a pharmacist.

He worked as an apprentice and later a "praticante" in his uncle's pharmacy, while simultaneously attending the National Lyceum in Lisbon. He became adept at manipulating natural products and so acquired an experience that he would later come to value in his medical work.

Studies in Lisbon

After completing his secondary education, he continued with preparatory studies at the Escola Politécnica de Lisboa (Lisbon Polytechnic School) in 1861, and then entered the Medical-Surgical School of Lisbon The knowledge he had acquired as a pharmacy practitioner helped him to graduate as a pharmacist in 1864, at the age of 21. After completing the course in pharmacy, Sousa Martins decided to continue his studies. In 1866 he completed the course in medicine as well, with a thesis dedicated to the musculature of the heart.

Medical career

In 1868 he was appointed, after a public competition, to the position of lecturer of the Medical Section of the Medical and Surgical School of Lisbon (today the medical faculty of the University of Lisbon). That same year, he was also elected member of the Society of Medical Sciences of Lisbon, beginning a career linked to teaching and research in the area of Medicine.

He had already been admitted to the Sociedade Farmacêutica Lusitana (Lusitanian Pharmaceutical Society) on 13 July 1864, and quickly assumed a pivotal role in the life of the society, authoring multiple reports and opinions over the next decade, and publishing several articles in its journal. As a long-standing member of the society's Public Health Commission, he played an important role in drawing attention to, and eventually regulating, various hazardous pharmaceutical practices. In 1867, he became a corresponding member of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Lisbon. He became an honorary member of the Pharmaceutical Society in appreciation of his role as the Portuguese representative at the International Sanitary Conference in Vienna in 1874.

Meanwhile, his career inside the Medical-Surgical School progressed, with appointments as senior lecturer in 1872, and extraordinary doctor of the Hospital of San José in 1874.[1]

By this time, Sousa Martins had earned himself a place among the intelligentsia of Lisbon. As a doctor and teacher, he attached great importance to the psychological and human component of medical practice, and included the following advice in his lectures:

"When you enter a hospital at night and you hear a patient groan, go to his bed, see what the poor sick man needs, and if you have nothing else to give him, give him a smile."[2]

Serra da Estrela and campaign against tuberculosis

His activity in the Hospital de San José, and in particular his efforts on behalf of the poorest patients, affirmed him as one of the highest regarded physicians in Portugal. He gained enormous prestige because of his fight against tuberculosis, which had reached epidemic proportions in Lisbon. Leading a scientific expedition to the Serra da Estrela mountain range, he advocated the construction in those mountains of sanatoriums intended for the combat of the disease.

In particular, Sousa Martins considered the Penhas Douradas formation near Manteigas to be the healthiest place in the country, thanks to its fresh and clean air. The scientific expedition to the Serra da Estrela had been organised under the aegis of the Lisbon Geographic Society, of which Sousa Martins was a founding member and member of the Central Council. Gathering in August 1881, a plethora of scientists and intellectuals came together to study the geographical, meteorological and anthropological aspects of the region in an unprecedented effort aimed at systematically exploring the Portuguese territory.

Following the expedition, Sousa Martins defended the implementation of sanatoriums in the mountain region, and was one of the founders of the foundation of Club Hermínio, a humanitarian association created in 1888 and active until at least 1892. Club Hermínio had the purpose of promoting the improvement of the natural conditions of the Serra da Estrela, through the establishment of health homes under medical supervision, the relief of poor patients and the exercise of hygienic control in the homes that were used by the patients.

Sousa Martins' main objective was the construction of a sanatorium in Serra da Estrela that could permanently host and treat patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. In spite of his efforts and influence with the Crown (he was an honorary doctor of the Royal House since 1888) and with the Government, the initiative, although universally supported, was slow to materialise, and the sanatorium he had proposed would not be built until after his death.

Illness and death

In 1897, Sousa Martins was delegated to the International Sanitary Conference, held in Venice, where he was elected vice president. Having already gotten ill in Venice, he returned to Lisbon very weak. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis and left for the Serra da Estrela for relief. Apparently convalescing, he retired to Alhandra, where he stayed in a farm that was owned by some of his friends, in an effort to convalesce.

However, the disease worsened and after he contracted cardiac problems in addition to what now seemed to be terminal tuberculosis, Sousa Martins committed suicide on 18 August 1897 using a large injection of morphine. Shortly before, he had confided to a friend: "Death is not stronger than I am" and "A doctor threatened with death by two diseases, both fatal, should be eliminated by himself."

In his eulogy of Sousa Martins, King Carlos I of Portugal said:

When he left the world, all the land that knew him wept. It was an irreparable loss, a national loss, with the greatest light of my kingdom fading away.

Legacy and cult

In 1904, a statue of Sousa Martins was erected in the Campo dos Mártires da Pátria in Lisbon, outside the current Faculty of Medicinal Sciences (New University of Lisbon). This statue has become the centre of a quasi-religious cult in which the spirit of Dr Sousa Martins is believed able to assist in cures. The foot of the statue is surrounded by marble plaques giving thanks to him for unexpected cures, some calling him "Brother", candles burn all around it and flowers are placed there.[3]

There are other sites of veneration too: the Cemetery of Alhandra, where he is buried; The Dr. Sousa Martins House Museum in Alhandra, and his bust in Largo 7 de Março, in downtown Alhandrense. On 7 March and 18 August of each year, the anniversaries of his birth and death, thousands of devotees visit and pray at his tomb and other places where he is represented.

Adherents of spiritism have claimed Sousa Martins as one of their own, although there is no evidence he ever showed any interest in the movement. However, followers have ascribed miraculous healings to their psychic communications with him.[4] Despite (or because) of its religious overtones, his veneration was never recognized by the Catholic Church but it remains until today.

Publications

- "O Pneumogástrico, os Antinomiais, a Pneumonia – Memória apresentada à Academia Real das Ciências de Lisboa", Tipografia da Academia Real das Ciências de Lisboa, Lisboa, 1867.

- A Patogenia Vista à Luz dos Actos Reflexos, Tese de Concurso, Tipografia Universal, Lisboa, 1868.

- Patogenia e Célula, 1868.

- "Relatório dos Trabalhos da Conferência Sanitária Internacional reunida em Viena em 1874, apresentado pelo delegado português a essa conferência J. T. Sousa Martins", Imprensa Nacional, Lisboa, 1874.

- "Relatório dos Trabalhos da Conferência Sanitária Internacional, reunida em Viena, em 1874", Imprensa Nacional, Lisboa, 1874.

- A Medicina Legal no Processo Joana Pereira, Resposta a uma consulta, Imprensa da Universidade, Coimbra,1878.

- "A Febre Amarela Importada pela Barca 'Imogene'", Tipografia Portuguesa, Lisboa, 1879.

- Os Typhos de Setúbal, Relatório sobre a Memória acerca dos typhos de Setúbal do sr. Dr. Francisco Ayres do Soveral e Parecer sobre essa memória por Sousa Martins, Imprensa Nacional, Lisboa, 1881.

- "Movimentos Pupilares Post-Mortem e Intra-Vitam", in Revista de Nevrologia e Psychiatria, Lisboa, 1888.

- A Tuberculose Pulmonar e o Clima de Altitude da Serra da Estrela, Imprensa Nacional, Lisboa, 1890.

- Discurso pronunciado na inauguração do Mausoléu Sobral na cidade da Guarda, Tipografia da Companhia Nacional Editora, Lisboa, 1894.

- "Comemoração de Louis Pasteur"", Discurso feito na Sociedade das Ciências Médicas de Lisboa, Tipografia Castro Irmão, Lisboa, 1895.

- Nosografia de Antero, in Antero de Quental, in Memoriam, Porto, 1896.

- Costumes da Occidental Praia – Evolução de uma Lei no Período Metafísico, Físico e Moral (published under the pseudonym of Zehobb Cêrvador), Tip. da Companhia Nacional Editora, Lisboa, 1890.

References

- ↑ Portuguese Wikipedia page on the São José hospital in Lisbon

- ↑ Carla Jesus, Sousa Martins, o santo que não acreditava em Deus. Selecções.pt, accessed 24 January 2018.

- ↑ "The 'miraculous' cures of Dr. Sousa Martins: once a doctor now a Saint & Memorial Statue Lisbon in front of the Faculty of Medicine". The Lisbon Connection. Accessed 1 October 2017

- ↑ Fernando Dacosta, Os Mal Amados, Casa das Letras, Lisboa, 2008

Bibliography

- "Sousa Martins (José Tomás de)", in: Esteves Pereira e Guilherme Rodrigues, Diccionario histórico, chorographico, heraldico, biographico, bibliographico, numismatico e artistico: Portugal: abrangendo a minuciosa descripção... de todos os factos notaveis da História portugueza,... Lisboa: João Romano Torres, Editor, 1904–1915. Vol. VI, pp. 1088–1090.

- Almeida, António Ramalho de, A tuberculose: doença do passado, do presente e do futuro. Porto: Bial, 1995.

- Almeida, António Ramalho de, O Porto e a Tuberculose. História de 100 Anos de Luta. Porto: Fronteira do Caos Editores, 2006.

- Forjac, Pereira, José Tomaz de Sousa Martins. Lisboa: Soc. Ind. Farmacêutica, 1970.

- Garnel, Maria Rita Lino, "Portugal e as Conferências Sanitárias Internacionais (Em torno das epidemias oitocentistas de cholera-morbus)", Revista de História da Sociedade e da Cultura, 9 (2009), pp. 229–251.

- Pais, José Machado. Sousa Martins e suas Memórias Sociais. Sociologia de uma Crença Popular. Lisboa: Gradiva, 1994.

- Repolho, Sara. Sousa Martins: Ciência e Espiritualismo. Coimbra: Imprensa da Universidade, 2008.

- Simões, Cunha, Dr. Sousa Martins: curas e orações. Tomar: Prima, 1991.

External links

- "The 'miraculous' cures of Dr. Sousa Martins: once a doctor now a Saint & Memorial Statue Lisbon in front of the Faculty of Medicine". The Lisbon Connection. Accessed 1 October 2017. (English).

- "Sousa Martins, O santo que não acreditava em deus". Seleccoes. Reader's Digest. Accessed 1 October 2017. (Portuguese: "Sousa Martins, the Saint not recognized by God")

- Dr Sousa Martins in facebook (Portuguese)

- Portrait of Sousa Martins, by Francisco Pastor (Portuguese)

- Biografia of dr. Sousa Martins (Portuguese)

- Museu de Alhandra, Casa Dr Sousa Martins (Portuguese)

- Página dedicada a Sousa Martins

- Centenário do Sanatório Sousa Martins

- Casa-Museu Dr. Sousa Martins na página oficial da Câmara Municipal de Vila Franca de Xira