The Russian Soviet Government Bureau (1919-1921), sometimes known as the "Soviet Bureau," was an unofficial diplomatic organization established by the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in the United States during the Russian Civil War. The Soviet Bureau primarily functioned as a trade and information agency of the Soviet government. Suspected of engaging in political subversion, the Soviet Bureau was raided by law enforcement authorities at the behest of the Lusk Committee of the New York State legislature in 1919. The Bureau was terminated early in 1921.

History

Establishment

Sometime in January 1919 a courier acting on behalf of the government of Soviet Russia contacted Ludwig C.A.K. Martens, a respected editor of Novyi Mir, the newspaper of the Russian Socialist Federation of the Socialist Party of America, appointing him its representative in the United States.[1][2] Arrangements were made to organize an office staff, including a commercial department headed by industrialist A.A. Heller,[3] a diplomatic department headed by former head of the Finnish Information Bureau, Santeri Nuorteva, and a legal department headed by Socialist Party leader Morris Hillquit.[2]

On March 19, 1919, Martens contacted the U.S. State Department in an effort to present the diplomatic credentials prepared for him by People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs Georgy Chicherin.[4] Chicherin authorized Martens to take over all real estate and property formerly held by the embassy and consulates of the Russian Provisional Government, to receive and disburse money on behalf of the Soviet government, and to solicit and answer all legal claims on behalf of Soviet Russia.[4]

With the economy of Soviet Russia on the verge of collapse, the administration of Woodrow Wilson was reluctant to grant formal diplomatic recognition, however, instead maintaining a wait-and-see attitude while allowing the Soviet government to establish a temporary agency in New York City.[5] The Russian Soviet Government Bureau (RSGB) was the stop-gap organization established by Martens in lieu of a recognized diplomatic embassy. The Bureau maintained offices at the "World Tower Building," located at 110 West 40th Street in Manhattan.[6]

A staff of 35 was hired, including a former editor of Novyi Mir and partisan of the Communist Labor Party, Gregory Weinstein, as office manager.[7] As administrative head, commercial attaché, and financial advisor, Julius Hammer, father of Armand Hammer, was assigned to generate support for the Russian Soviet Government Bureau and funded the Bureau by money laundering the proceeds from illegal sales of smuggled diamonds through his company Allied Drug while his Allied Drug partner, Abraham A. Heller, headed the Bureau's commercial department.[3] The nature and activity of the Soviet Bureau ventured into uncharted water, as historian Theodore Draper noted:

"There were no precedents for Martens' bureau. It was set up as a diplomatic mission, without diplomatic recognition. It was made up mostly of Americans, and the others, like Martens himself, had been cut off for many years from direct contact with Russia. Couriers constituted the only method of communication, but they were so slow and uncertain that it took two months for Martens to get in touch with the Soviet government."[7]

A secret mission to Russia in March 1919 conducted by Wilson administration envoy William C. Bullitt to assess the economic and political system there ended in a negative report which accentuated various atrocities committed in the name of the Bolshevik regime, effectively removing any chance of formal recognition of the Martens initiative.[5] Despite the decision to forego formal recognition, the State Department did not immediately seek the removal of Martens, instead opting to advise Americans to use "extreme caution" in their dealings with the Soviet Bureau.[8]

Trade agency

With its chances of gaining official recognition clearly dashed from the outset, the Soviet Bureau concentrated its efforts on building commercial contacts with American businesses. Martens sought to take over assets previously held by the Provisional Government and to use these funds as part of a $200 million program to acquire commodities and capital goods for the struggling Bolshevik government of Russia.[9] Martens declared that with the overthrow of the Provisional Government in the Russian Revolution of 1917, the position of ambassador Boris Bakhmeteff had become vacant and the assets formerly held legally transferred to the new regime.[9]

While the effort to obtain massive assets came to naught, contacts with American companies eager to do business with Soviet Russia came fast and furious. By the end of the first month, Martens' right-hand man, the Finnish socialist Santeri Nuorteva, declared to the press that "we are swamped with requests for commercial connections."[10]

This tempo was accelerated in April 1919, when the RSGB mailed letters of inquiry to 5,000 American firms and circulated press kits to 200 trade-oriented newspapers.[11] Numerous firms took interest and sent their representatives to New York for direct discussions with Martens and his associates, including such industrial giants as the Ford Motor Company, meatpackers Armour and Company and Swift and Company, agricultural machinery maker International Harvester, cotton goods maker Marshall Field and Company, and Sears, Roebuck and Company.[12]

Indeed, during its brief period of active operations as a Soviet trade agency, terminated by a June 12, 1919 raid, the RSGB was contacted by an estimated 941 American companies seeking to sell products to or to obtain products from Soviet Russia.[13] By the end of 1919, the Russian Soviet Government Bureau had signed contracts totaling nearly $25 million.[14] This proved to be the first of a growing flood of commerce, with Soviet contracts with American companies topping the $300 million mark by May 1920.[14]

Propaganda agency

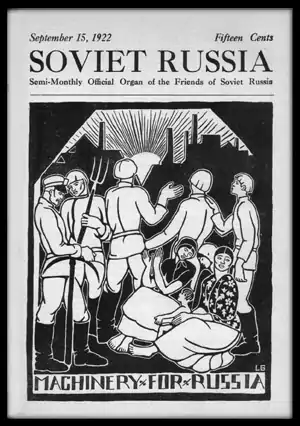

In addition to its role as the trade agency of the Soviet Russian government in America, the RSGB also served a propaganda function, attempting to counteract "the campaign of deliberate misrepresentation which is being waged by enemies of the Russian workers" in the press.[15] The Soviet Bureau published a weekly informational bulletin from its earliest days, moving to a magazine format with the title Soviet Russia: A Weekly Devoted to the Spread of Truth About Russia effective June 9, 1919.[16]

Soviet Russia included reprints of speeches by RSGB officials,[17] news and commentary supporting the Soviet side in the ongoing Russian Civil War,[18] and the pronouncements of top Soviet government officials on matters of trade and world politics.[19]

While the publication of such fare seemed reasonable to the Soviet Bureau and its political supporters, the presence of a Bolshevik propaganda agency in the heart of New York City was a proverbial red flag to conservative opponents of the Soviet regime. The Russian Soviet Government Bureau became a top target of the so-called Lusk Committee established by the New York state legislature to investigate radical activities in the state of New York.

Relationship with the American Communist movement

Martens and his staff accepted a number of invitations to speak at radical meetings in New York City and elsewhere, activity which drew the ire of conservative forces in America.[20] Martens retained close contact and warm relations with the Socialist Party of America (SPA) and the Communist Labor Party of America (CLP) which emerged from the SPA's organized left wing late in 1919.[20]

Relations with the rival Communist Party of America (CPA) were frosty, however, as the powerful Russian Federation of that organization sought to control the activities and purse of Martens and the Soviet Bureau in America.[20] A historian has summarized the perspective of the communist wing of the Russian colony in America neatly:

The leaders of the Russian federation ... did not hesitate to extend their jurisdiction over the official Soviet agency ... They felt that commercial and trade relations were foolish objectives. Only the spread of the proletarian revolution mattered. If the revolution conquered outside Russia, then commercial and trade relations would come of themselves. If the world revolution failed, commercial and trade relations could not help the Russian Revolution to survive. In effect, the American Russians had taken literally what the Russian leaders themselves were saying about the necessity for a world revolution to save the Russian Revolution, and in doing so, they became more doctrinaire than their teachers."[21]

While Commissar of Foreign Affairs Chicherin ultimately sided with Martens in maintaining financial and organizational independence from the CPA, relations between the Soviet Bureau and the party were stilted.[20]

Raid

On March 28, 1919 and April 11, 1919 The New York Times published articles urging to close what it deemed the illegal representation of the Soviet Bureau.

New York's Lusk Committee and a number of government agencies conducted inquiries of the RSGB prior to its office being raided, including investigations by the U.S. Department of Justice, the U.S. Treasury Department, the Directorate of Military Intelligence, and the War Trade Board.[22][23] Information was provided as requested, with Soviet Bureau official Evans Clark noting to assistant director of the War Trade Board G.M. Bodman at a meeting on April 25, 1919, that the bureau "had nothing to conceal" and was "glad to furnish information to those entitled to have it."[23] Additionally, Martens and his lawyer Charles Recht had met personally with officials of the Department of Justice in April and May, while Clark travelled to Washington, D.C. to consult with the personal secretary of U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer.[24]

While federal officials seem to have taken a "wait and see" attitude towards the Soviet Bureau, New York state politicians and law enforcement authorities were motivated by a more urgent agenda. On Thursday, June 12, 1919, the RSGB's offices on West 40th Street were suddenly raided by New York Police at the behest of the state legislature's newly established Joint Legislative Committee Investigating Seditious Activities (commonly known as the "Lusk Committee").[22][25] A search warrant was served[25] and "every shred of written or printed paper" was removed from the premises,[26] material which was later parsed at the Lusk Committee's leisure for evidence of illegal seditious activity and further radical connections for the committee to explore.

The Soviet Bureau vociferously protested the Lusk Committee's action:

The invasion of the office of the Russian Soviet Government was altogether unwarranted and illegal. The Russian Soviet Government Bureau has conscientiously refrained from interfering in American affairs. Its activities have always been open to investigation by anyone honestly in search of information about Soviet Russia or about the activities of the Bureau. Only the existing state of hysterical reaction diligently nursed by a persistent campaign of slander against Soviet Russia can explain why such drastic steps were taken in a case where a simple inquiry would have brought out all the information necessary — without breaking the law and the first principles of international hospitality."[26]

Martens, who had gone underground and often hid at Julius Hammer's home, was subsequently subpoenaed and called before the committee to give testimony.[22][25]

Hearings

The organization was a subject of hearings in United States Senate from January through March 1920. On December 17, 1920, the United States Department of Labor decided to deport Martens.

In January 1921 Martens finally left the United States. Work of the organization stopped with the departure of its leader.

Key participants

|

|

|

Publications

- Official organs

- Information Bulletin —Small weekly newspaper first issued March 3, 1919.

- Soviet Russia —Weekly magazine first issued June 7, 1919.

- Volume 1: June to December 1919.

- Volume 2: January to June 1920.

- Volume 3: July to December 1920.

- Volumes 4 and 5: 1921.

- Volumes 6 and 7: 1922.

- Volume 8: 1923.

- Volume 9: 1924. —Called Soviet Russia Pictorial, terminated October 1924.

- Pamphlets

- The Labor Laws of Soviet Russia: With an Answer to a Criticism by Mr. William C. Redfield. Third Edition. New York: Russian Soviet Government Bureau, 1920.

- The Marriage Laws of Soviet Russia: Complete Text of First Code of Laws of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic Dealing with Civil Status, Domestic Relations, Marriage, the Family and Guardianship. New York: Russian Soviet Government Bureau, 1921.

See also

- Amtorg Trading Corporation aka AMTORG (NYC)

- All Russian Co-operative Society aka ARCOS (London)

References

- ↑ Epstein, Edward Jay (1996). Dossier: The Secret History of Armand Hammer. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0679448020.

- 1 2 Archibald E. Stevenson (ed.), Revolutionary Radicalism: Its History, Purpose and Tactics with an Exposition and Discussion of the Steps being Taken and Required to Curb It ... : Part 1: Revolutionary and Subversive Movements Abroad and At Home, Vol. 1. Albany, NY: Lyon, 1920; pg. 643.

- 1 2 Epstein 1996, p. 40.

- 1 2 Todd J. Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare: The Lusk Committee and New York's Crusade Against Radicalism, 1919-1923. New York: Routledge, 2003; pg. 37.

- 1 2 Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare, pg. 38.

- ↑ Stevenson (ed.) Revolutionary Radicalism, vol. 1, pg. 639.

- 1 2 Theodore Draper, The Roots of American Communism. New York: Viking Press, 1957; pg. 162.

- ↑ Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare, pg. 39.

- 1 2 Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare, pg. 45.

- ↑ New York Times, March 28, 1919. Cited in Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare, pg. 46.

- ↑ Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare, pg. 56.

- ↑ Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare, pp. 56-57.

- ↑ Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare, pg. 58.

- 1 2 Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare, pg. 62.

- ↑ "To the Reader," Soviet Russia, vol. 1, no. 1 (June 7, 1919), pg. 1.

- ↑ Masthead, Soviet Russia, vol. 1, no. 1 (June 7, 1919), pg. 1.

- ↑ See, for example, Santeri Nuorteva, "Trade Possibilities in Soviet Russia: Speech at the Knit Goods Manufacturers' Convention in Philadelphia, June 4th," Soviet Russia, vol. 1, no. 2 (June 14, 1919), pp. 9-10.

- ↑ See, for example, Max M. Zippin, "The Antisemitism of the Koltchak Government," Soviet Russia, vol. 1, no. 3 (June 21, 1919), pp. 4-6.

- ↑ See, for example, Yuri Larin, "Economic Reconstruction in Soviet Russia at the End of February, 1919," Soviet Russia, vol. 1, no. 3 (June 21, 1919), pp. 8-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Stevenson (ed.), Revolutionary Radicalism, vol. 1, pg. 644.

- ↑ Draper, The Roots of American Communism, pp. 162-163.

- 1 2 3 Epstein 1996, p. 42.

- 1 2 Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare, pg. 63.

- ↑ Pfannestiel, Rethinking the Red Scare, pp. 63-64.

- 1 2 3 Stevenson (ed.), Revolutionary Radicalism," vol. 1, pg. 641.

- 1 2 Introductory editorial, Soviet Russia, vol. 1, no. 3 (June 21, 1919), pg. 3.

Further reading

- "Stevenson's 'Personally Conducted' Raid," New York Call, vol. 12, no. 166 (June 15, 1919), pg. 8.

- Ludwig C.A.K. Martens, "Soviet Envoy Martens' Farewell Message to America," The Toiler, whole no. 157 (Feb. 5, 1921), pg. 1.

- Ludwig C.A.K. Martens, "Statement of Ludwig C.A.K. Martens on the Activities of the Soviet Mission: Moscow — Feb. 24, 1921." Department of Justice Bureau of Investigation files, NARA M-1085, reel 934. Corvallis, OR: 1000 Flowers Publishing, 2007.

- Archibald E. Stevenson (ed.) Revolutionary Radicalism: Its History, Purpose and Tactics with an Exposition and Discussion of the Steps being Taken and Required to Curb It: Filed April 24, 1920, in the Senate of the State of New York, Published in 4 volumes. Part 1: Revolutionary and Subversive Movements Abroad and At Home, Vol. 1. Albany, NY: Lyon, 1920.

External links

- Tim Davenport, "Russian Soviet Government Bureau (1919-21)", Early American Marxism website, www.marxisthistory.org/