| St. Matthew's German Evangelical Lutheran Church | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) St. Matthew's German Evangelical Lutheran Church | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Evangelical Lutheran Church in America |

| District | South Carolina Synod |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Congregation |

| Leadership | The Rev. Eric Childers, Senior Pastor

Rev. Rebecca Wicker, Associate Pastor for Outreach and Evangelism Jason Bazzle, Organist and Director of Music |

| Location | |

| Location | 405 King Street, Charleston, South Carolina, U.S.A. |

| Geographic coordinates | 32°47′12″N 79°56′14″W / 32.7868°N 79.9372°W |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | John Henry Devereux |

| Style | Gothic Revival |

| Completed | 1872 |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | North East |

| Capacity | 765+ |

| Length | 157 ft (48 m) |

| Width | 64 ft (20 m) |

| Width (nave) | 56 ft (17 m) |

| Spire(s) | 1 |

| Spire height | 255 ft (78 m) |

| Materials | cement render over brick |

| Website | |

| St. Matthew's Lutheran Church | |

The German Evangelical Lutheran Church of Charleston, South Carolina, was incorporated on December 3, 1840. Through usage and custom the Church is now known as St. Matthew's German Evangelical Lutheran Church or St. Matthew's Lutheran Church and is a member of the South Carolina Synod of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America.

History

The church was founded by Johann Andreas Wagener and 49 other German-speaking citizens wishing to worship in their native language in the port city of Charleston, South Carolina. Wagener's first intent was to form a German language, "ecumenical, cosmopolitan" congregation for all faiths: Lutheran, Reformed, and Catholic.[1] However, when the ecumenical plan failed, it was decided to organize the congregation as an Evangelical Lutheran Church. Wagener was elected the congregation's first president. He established the town of Walhalla, South Carolina, in 1849 as a colony for German immigrants. Later he became a brigadier general in the Confederate States Army and served as the Commandant of Charleston until the evacuation of the city in February 1865.[2] In 1866, he represented the Charleston district in the South Carolina House of Representatives, and in 1871, was elected mayor of Charleston.[3]

The congregation's first purchase was a cemetery for the burial of German-speaking citizens during a yellow fever outbreak in 1841. Known as Hampstedt or God's Acre Cemetery, the ground on Reid Street held 1,048 graves by the mid-1850s.[4] During the first year of the congregation's organization, worship services were held in the Lecture Room of the Second Presbyterian Church at 63–65 Society Street, the German Fire Company at 6 Chalmers Street, and the Lecture Room at St. John's Lutheran Church (English) on Clifford St. (formerly known as Dutch Church Alley).[5] The Presbyterian Lecture Room was later purchased by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Charleston in 1861 to form St. Paul's German Catholic Church.[6] The Lutheran congregation's first church building was a classical Greek Revival structure on the northwest corner of Hasell and Anson Streets. The architect was Edward Brickell White, and it was dedicated on June 22, 1842. The cost for the land and construction by John Dawson was $11,000.

In 1856, the church purchased Bethany Cemetery because the first cemetery was full. There were several additional yellow fever outbreaks during the early years of the congregation. According to church records, there were 147 deaths in 1854, 308 in 1858, and 130 in 1865, of which 84 were children.[7] During the worst outbreaks, Pastor Ludwig "Louis" Müller officiated at three funerals every day.

During the American Civil War, only the sanctuary windows and some furnishings were damaged during the Siege of Charleston. By 1860, Germans represented 5% of the Charleston population.[8] The congregation had outgrown the original sanctuary by 1868 when 40 applications for pews could not be filled.[7] In 1878 the sanctuary was sold to a group of 53 Lutherans who formed the German Evangelical Lutheran St. Johannes Church.[9]

In 1868, the church purchased its present site from Father Patrick O'Neill and contracted the Irish-born architect John Henry Devereux[10] to design a Gothic revival sanctuary with suggestions from Ludwig Müller, the congregation's pastor. Devereux also designed the Renaissance Revival U.S. Post Office in Charleston. The new sanctuary was dedicated in 1872 with elaborate ceremonies and 3000 persons attending. In 1883, the church began to hold services in German and English. In 1901, a clock and set of ten bells from the Meneely Bell Foundry were installed in the steeple at a cost of $7,000. (Three additional bells were installed in 1966, when the steeple was rebuilt after a fire.) A Sunday school building was added in 1909. As the nation entered the World War I in 1917, 83 members of the church joined the military; five paid the supreme sacrifice.[7] Due to anti-German sentiments during World War I, German language services had ended by 1918. The sanctuary was renovated in 1925 with an elaborate Gothic marble altar installed and an addition of a 5-stop chancel organ. In 1932, during one of the worst years of the Great Depression, an expansive Sunday school building was constructed at the cost of $81,000.

In 1941, joint services were started in the Sunday school building for armed service personnel stationed in Charleston. A program of singing, entertainment, and a social hour were held each Sunday evening during the duration of World War II. In 1944, a Service Center Building was constructed on St. Matthew's property on Vanderhorst Street by the National Lutheran Council, a cooperative body comprising eight Lutheran church bodies in the United States, who then created the Service Commission. This commission served as the official military agency of the council and worked to provide spiritual ministry to service personnel.[11] Also during the war, German hymnals were loaned to the German prisoner of war camp in Hampton, South Carolina.[12] The church's organist and a vocal quartet presented a program of Christmas music to the prisoners, also. In World War II, 191 members of St. Matthew's served their country; three of them were killed.[13]

In 1961, the final expansion and renovation of the parish buildings was completed, which included an auditorium and the air conditioning of the sanctuary and Sunday school building.

St. Matthew's plays host to many cultural events throughout the year and broadcasts its Sunday 11:00 AM service live on WSCC-FM 94.3. Professor Stefan Engels of Leipzig, Germany noted scholar on the works of Sigfrid Karg-Elert has performed many times on the 61 rank Austin Organ. Opus No. 2085 |South Carolina| |Charleston| |St. Matthew's Evan. Luth.| 3 55[14] The church is also a frequent venue for Charleston Symphony Orchestra Gospel Choir concerts.

Church founder Gen. Johann Andreas Wagener with wife Maria Eliese Wagener.

Church founder Gen. Johann Andreas Wagener with wife Maria Eliese Wagener. Hampstedt Cemetery was purchased to inter victims of the numerous yellow fever outbreaks in the nineteenth century.

Hampstedt Cemetery was purchased to inter victims of the numerous yellow fever outbreaks in the nineteenth century. The German Fire Company headquarters was one of three worship sites for the congregation before 1842.

The German Fire Company headquarters was one of three worship sites for the congregation before 1842. The original St. Matthew's Sanctuary built in 1842.

The original St. Matthew's Sanctuary built in 1842. The dedication stone of the original sanctuary written in German.

The dedication stone of the original sanctuary written in German. Bethany is St. Matthew's second and current cemetery. It has many examples of Victorian mortuary sculpture.

Bethany is St. Matthew's second and current cemetery. It has many examples of Victorian mortuary sculpture. Gates in Bethany by Christopher Werner. One of Charleston's highly regarded nineteenth century ironworkers.

Gates in Bethany by Christopher Werner. One of Charleston's highly regarded nineteenth century ironworkers.

The fire of 1965

On January 13, 1965, at approximately 6:50 pm, smoke was discovered coming from the church building. An incandescent light had ignited some painting materials in the church. Soon flames engulfed the roof. The fire appeared to be under control by 8:45 pm. However, increasing winds spread the fire to the steeple, and at 10:00 pm the structure fell directly in front of the church, plunging 18 feet (5.5 m) into the courtyard where it remains as a memorial of the tragic event. Rather than relocate to the suburbs where most of the church members lived, the congregation decided to rebuild the historic structure. A survey of the damage showed that the chancel and all but one ground floor stained glass windows were intact. Also, the chancel furniture, altar hangings, and "wine glass" pulpit were saved. The destroyed gallery stained glass windows were replaced by Franz Mayer & Co. of Munich, Germany, and executed by the studios of George L. Payne of Paterson, New Jersey.[15] The destroyed windows in the front of the church were replaced by the Hunt Stained Glass Studios of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who had installed the originals. The first service in the restored sanctuary was on June 12, 1966.

January 13, 1965.

January 13, 1965. January 14, 1965.

January 14, 1965. The top 18 feet (5.5 m) of the steeple remain embedded in the ground next to the sanctuary.

The top 18 feet (5.5 m) of the steeple remain embedded in the ground next to the sanctuary.

Hurricane Hugo

When Hurricane Hugo’s 135-mile-per-hour (217 km/h) winds swept across the peninsula of Charleston at midnight on September 21, 1989, no building was left untouched, including St. Matthew's sanctuary. On Sunday morning September 24, 135 members gathered in the water-logged and darkened nave to assess the damage and offer prayer that the structure was basically still intact. Damage to the 117-year-old structure, however, was significant.

The entire steeple was denuded of its copper sheathing, large sections of the slate roof were blown off which damaged the building’s drainage system and gutters, other slate tiles damaged the adjacent educational building. Large sections of stucco were stripped from the exterior walls. Water filled the "dead-air space" of the nave walls, necessitating the resurfacing of all interior walls and the vaulted ceiling. It was also necessary to restore the decorative brackets and ornamental cherubs throughout the nave. All carpets and parquet flooring had to be replaced. Restoration and renovation of the entire facility cost over $1.6 million and took almost two years. On September 21, 1990, two years to the day after the "storm of the century", the nave and the educational building were rededicated, with South Carolina Synod Bishop James Aull leading the congregation in a service of praise and thanksgiving.[16]

The Community Center at St. Matthew's

In 1999, St. Matthew's Lutheran Church launched a $1.2 million capital fund appeal to purchase and restore a historic circa 1810 building adjacent to the sanctuary to function as a Community Outreach Center. The architect, Glenn Keys, used a photo from 1883 to guide his design. According to Sanborn maps from May 1884, the building was a boot and shoe store.[17] Since the fall of 2000, the Community Outreach Center at St. Matthew's has provided a range of services to the surrounding downtown community. This active, community ministry arm of St. Matthew's Lutheran Church is hospitable, vibrant, and welcoming. Current activities include English as Second Language instruction, a Lowcountry Food Bank affiliated Emergency Food Pantry, Holiday Care bags for the homebound elderly, and ongoing support for Charleston's Cinderella Project for teen girls now held at John Wesley United Methodist in West Ashley, which originated at the center in 2001.

In 2016, Charleston's mayor, John Tecklenburg, created a Homeless to Hope initiative to address the growing homeless population. The Community Center is the host for the Next Steps of Barnabas ministry program to work with individuals to end their homelessness. Volunteers from 14 Charleston area churches were trained to mentor those in transition. In addition, the Community Center also provides direct emergency financial relief via a Sharing With A Neighbor (SWAN) program for items such as eviction and water shut off, utility bill assistance and other human concerns for families and individuals. To fund programs, the center relies on grant income, donations and fundraisers such as an annual charity boutique called Tea Time Treasures during Spoleto Festival USA, a fall Oktoberfest and a Christmas Charity boutique in December. In 2017, Lutheran Services Carolinas opened the Charleston office for immigration and refugee services housed in the center. This successful collaboration involved the city of Charleston, the U.S. Dept. of State and Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services (LIRS). The LIRS office clients benefited from ESL classes, employment assistance and citizenship opportunities for those interested.

The Community Center building in 1883 when it was a Boot & Shoe store.

The Community Center building in 1883 when it was a Boot & Shoe store. The Community Center of St. Matthew's as restored to its 1883 appearance.

The Community Center of St. Matthew's as restored to its 1883 appearance. The Community Center supports its programs through a fundraiser during the Spoleto USA Festival.

The Community Center supports its programs through a fundraiser during the Spoleto USA Festival.

The building

The structure is most known for the height of its steeple, which at 255 feet (78 m), was the tallest building in South Carolina until the completion of the Tower at 1301 Gervais in 1973. It remains the tallest church steeple in the state.[18][19][20][21][22] The building is 65 feet (20 m) wide by 157 feet (48 m) deep. Above the vestibule rise the tower and spire. At a height of 135 feet (41 m) from the ground, the tower takes an octagonal shape, then reaches upward to the terminal height of 255 feet 5⁄8 inch (77.740 m). The spire was originally topped by a wrought iron finial made by German-born Christopher Werner, who also created the Palmetto Monument[23] on the state capitol grounds in Columbia, South Carolina. The finial was destroyed in the cyclone of 1885 and not replaced due to cost. The nave is 100 feet (30 m) long by 56 feet (17 m) wide and the vaulted ceiling rises 72 feet (22 m) above the box pews. Originally the interior and exterior were painted in a faux stone finish, and in the 1880s, the exterior displayed a black and white Ablaq banded effect. Presently the interior is white and the exterior is plastered in medium red. St. Matthew's is listed as an exceptional contributing property of the Charleston Old and Historic District and is a contributing building in the Charleston National Historic Landmark District.[24]

A rare 1883 view of the Christopher Werner finial and ablaq banded exterior finish.

A rare 1883 view of the Christopher Werner finial and ablaq banded exterior finish. Looking up to the 255' 5/8" tall spire.

Looking up to the 255' 5/8" tall spire. St. Matthew's Chancel

St. Matthew's Chancel The "wine glass" pulpit and sounding board of 1872 survived the fire of 1965

The "wine glass" pulpit and sounding board of 1872 survived the fire of 1965 The marble baptism font inscribed in German

The marble baptism font inscribed in German Carved Lindenwood Statue of Christ the Good Shepherd.

Carved Lindenwood Statue of Christ the Good Shepherd. The Eagle lectern

The Eagle lectern St. Matthew's Chapel

St. Matthew's Chapel The Education Building and Heritage Court

The Education Building and Heritage Court St. Matthew's Angle view

St. Matthew's Angle view

The organs

Gallery organ

After the fire of 1965, a new sanctuary instrument by Austin Organs, Inc. was dedicated in 1967.[14] It has 3 manuals, 47 stops, 61 ranks and electropneumatic action. The Austin Organ Opus 2465 stop list:

GREAT (unenclosed) 16 Gemshorn, 8 Principal, 8 Bourdon, 8 Gemshorn (ext), 4 Octave, 4 Spitzflote, 2 Waldflote, II Rauschquint, IV Fourniture, Cymbelstern, Chimes, Gt-Gt 16, 4, Sw-Gt 16, 8, 4, Ch-Gt 16, 8, 4, Pos-Gt 8,

SWELL (enclosed) 16 Lieblich Gedackt, 8 Geigen Principal, 8 Hohl Flute, 8 Gamba, 8 Gamba Celeste, 4 Principal, 4 Rohrflote, 2 Flautino, IV Plein Jeu, 16 Contra Fagotto, 8 Fagotto (ext), 4 Clairon, 8 Trumpet, Sw-Sw 16, 4, Ch-Sw 8, Ch-Pos 8,

CHOIR (enclosed) 8 Nason Flute, 8 Flauto Dolce, 8 Flute Celeste, 4 Koppelflote, 2 2/3 Nasard, 2 Blockflote, 1 3/5 Tierce, 8 Krummhorn, 8 Bombarde, 8 Trumpet en chamade, Tremulant, Ch-Ch 16, 4, Sw-Ch 16, 8, 4, Gt 8; Pos 8,

CHANCEL (enclosed) 8 Gedackt, 8 Viole d'amour, 8 Viole celeste, 4 Principal, 4 Chimney Flute, III Mixture, 8 Trompete, Tremulant, Chancel on Great, Chancel on Choir,

POSITIV 8 Suavial, 4 Praestant, 2 Prinzipal, 1 1/3 Larigot, III Cymbel, 4 Schalmei,

PEDAL 32 Resultant (ext), 32 Lieblich Gedackt (electronic), 32 Contra Bombarde (electronic), 16 Principal, 16 Bourdon, 16 Gemshorn (Gt), 16 Lieblich Gedackt (Sw), 16 Flauto Dolce (Ch ext), 8 Octave, 8 Gemshorn (Gt), 8 Gedeckt (ext), 4 Choralbass, III Mixture, 16 Bombarde (Ch ext), 16 Fagotto (Sw), 8 Bombarde (Ch), 4 Krummhorn (Ch), 16 Gedeckt (Chancel), 8 Floete (Chancel), Chimes (Gt), Gt-Ped 8, 4; Sw-Ped 8, 4; Ch-Ped 8, 4; Pos-Ped 8

Chapel organ

In 2001, St. Matthew's obtained the Ontko Pipe Organ Opus 19a for use in the Education Building Chapel. The organ has 2 manuals, 5 registrations, and 7 ranks with electronic action. The Ontko Opus 19a stop list:

- Manual One: 8 Bourdon, 4 Prestant, 4 Quintaton, 2 Flute a bec, Cymbale III, 8 Trompette

- Manual Two: 8 Quintaton, 4 Flute a Cheminee, 2 Doublette, 1 1/3 Larigot, 8 Trompette, Tremulant

- Pedal: 16 Quintaton, 8 Bourdon, 4 Prestant, 8 Trompette

Stained glass windows

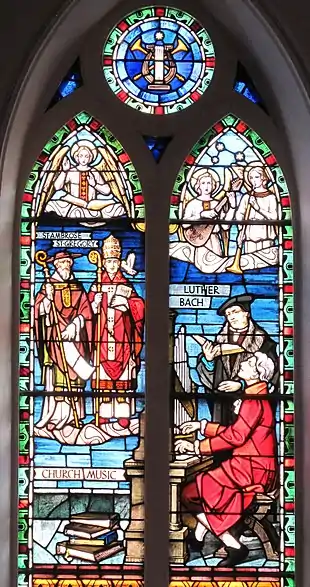

There are noteworthy stained glass windows in the sanctuary. The chancel contains the original 1872 Henry E. Sharp depictions of the Crucifixion and the four Evangelists. In 1912, 12 opalescent memorial windows were installed on the ground floor. These windows have been attributed to the Quaker City Stained Glass Company of Philadelphia. Of special merit are the two full-length windows of Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon. During the fire of 1965, sixteen windows in the upper gallery and organ loft were destroyed. Only the window of the Nativity at the rear of the south gallery was not damaged. This original window and its companion replacements, the Annunciation and the Holy Apostles, were products of the Hunt Studios in Pittsburgh. The remaining replacement gallery windows were by the studio of Franz Mayer & Co. of Munich, Germany represented by the studios of George L. Payne of Paterson, New Jersey.

Church Music – Music has always been important to the Lutheran Church. The window shows Lutherans, Bach and Luther, and two hymnists from the early church, Ambrose and Gregory.

Church Music – Music has always been important to the Lutheran Church. The window shows Lutherans, Bach and Luther, and two hymnists from the early church, Ambrose and Gregory. Abraham – The patriarch, standing on Mt. Horeb, receives the angel's message to sacrifice the ram in place of his son, Isaach.

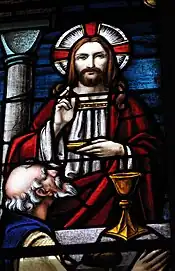

Abraham – The patriarch, standing on Mt. Horeb, receives the angel's message to sacrifice the ram in place of his son, Isaach. Holy Communion – In the Sacrament of the Altar, our Lord breaks the bread of his body and offers the wine of his true blood to the disciples. The circle is for the sacraments.

Holy Communion – In the Sacrament of the Altar, our Lord breaks the bread of his body and offers the wine of his true blood to the disciples. The circle is for the sacraments. Prince of Peace – All the prophets look forward to the coming of Jesus Christ, the Prince of Peace.

Prince of Peace – All the prophets look forward to the coming of Jesus Christ, the Prince of Peace. Creation – Here are depicted the days of creation: light/darkness; heaven; vegetation; sun, moon, stars; fowl, fish of the sea; beast, man; rest. The hand of God is shown giving life to man.

Creation – Here are depicted the days of creation: light/darkness; heaven; vegetation; sun, moon, stars; fowl, fish of the sea; beast, man; rest. The hand of God is shown giving life to man.

David – The boy David is shown with the head of the giant and later as King David in power. He was selected by Samuel and God.

David – The boy David is shown with the head of the giant and later as King David in power. He was selected by Samuel and God. The Second Coming of Christ – His robes are those of a ruler and king and contrast greatly with the humbleness of his first Advent.

The Second Coming of Christ – His robes are those of a ruler and king and contrast greatly with the humbleness of his first Advent. Moses – Moses on Mt. Sinai holds the two tablets of stone. They are inscribed not with the Ten Commandments, but with the New Testament summary of the Old Testament law. The burning bush indicates the presence of God and the revelation of his will. The circle at the top shows the Lutheran divisions of the Ten Commandments: the first 3 are duties to God; the last 7 are duties to man.

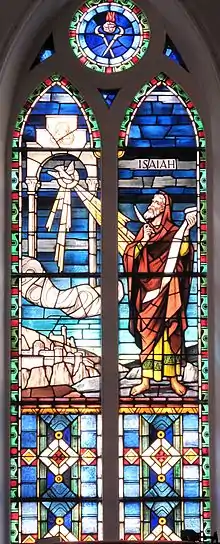

Moses – Moses on Mt. Sinai holds the two tablets of stone. They are inscribed not with the Ten Commandments, but with the New Testament summary of the Old Testament law. The burning bush indicates the presence of God and the revelation of his will. The circle at the top shows the Lutheran divisions of the Ten Commandments: the first 3 are duties to God; the last 7 are duties to man. Isaiah – The evangelical prophet receives his vision of the Lord's house, which shall be established on the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hill.

Isaiah – The evangelical prophet receives his vision of the Lord's house, which shall be established on the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hill. Elijah – The prophet of fire, a prototype of John the Baptizer, stands on Mt. Carmel before the altar he has built. The prophets of Baal stand before their altar. Elijah's offering is consumed by fire that comes down from heaven, and the people are convinced Yahweh is the true and living God.

Elijah – The prophet of fire, a prototype of John the Baptizer, stands on Mt. Carmel before the altar he has built. The prophets of Baal stand before their altar. Elijah's offering is consumed by fire that comes down from heaven, and the people are convinced Yahweh is the true and living God. Word of God – With the sacrament (the "Word made visible") Lutherans gladly hear and receive the Word of God – Jesus Christ – as he is preached from the pulpit of the church and as his Word is read from the lectern and the altar. Lutherans believe in a proper balance of Word and Sacrament.

Word of God – With the sacrament (the "Word made visible") Lutherans gladly hear and receive the Word of God – Jesus Christ – as he is preached from the pulpit of the church and as his Word is read from the lectern and the altar. Lutherans believe in a proper balance of Word and Sacrament.

The Annunciation – The angel of God announces to the Virgin Mary that she is to be the mother of Jesus, the Messiah. The symbols in the window relate to Mary. The circle at the top is the "fleur-de-lis," symbol of the Virgin Mary.

The Annunciation – The angel of God announces to the Virgin Mary that she is to be the mother of Jesus, the Messiah. The symbols in the window relate to Mary. The circle at the top is the "fleur-de-lis," symbol of the Virgin Mary. The Nativity – The glory of the first Christmas Day is celebrated in the window of the Holy Family. The artist depict Jesus' humble birth. This is the only gallery window that survived the fire of 1965 which destroyed the nave. Only one piece of glass was broken! The circle shows the star of Bethlehem.

The Nativity – The glory of the first Christmas Day is celebrated in the window of the Holy Family. The artist depict Jesus' humble birth. This is the only gallery window that survived the fire of 1965 which destroyed the nave. Only one piece of glass was broken! The circle shows the star of Bethlehem. Reformation – Martin Luther is seen with the Ninety-five Theses which were posted on the Castle Church door at Wittenberg, Germany. Various cities important to the life of the great reformer are depicted in the city shields. The Diet of Worms and Augsburg are shown with King Charles presiding. It was there that Luther uttered the immortal quote, "Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise. God help me!" The buildings of St. Matthew's and St. Johannes, the original St. Matthew's sanctuary, are shown at the top of this window.

Reformation – Martin Luther is seen with the Ninety-five Theses which were posted on the Castle Church door at Wittenberg, Germany. Various cities important to the life of the great reformer are depicted in the city shields. The Diet of Worms and Augsburg are shown with King Charles presiding. It was there that Luther uttered the immortal quote, "Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise. God help me!" The buildings of St. Matthew's and St. Johannes, the original St. Matthew's sanctuary, are shown at the top of this window. Philip Melanchthon – He was a German scholar and humanist who wrote the Augsburg Confession. He is second only to Luther as the chief figure of the Reformation.

Philip Melanchthon – He was a German scholar and humanist who wrote the Augsburg Confession. He is second only to Luther as the chief figure of the Reformation. Ascension of Christ – Christ was lifted up before their eyes and a cloud took him from their sight. Acts 1:9

Ascension of Christ – Christ was lifted up before their eyes and a cloud took him from their sight. Acts 1:9 Angel of the Lord – An angel of the Lord appearing to shepherds in the field with a star over the manger. Luke 1:8-10

Angel of the Lord – An angel of the Lord appearing to shepherds in the field with a star over the manger. Luke 1:8-10 Jesus at the Door – "Behold, I stand at the door, and knock... and if any hear my voice and will open the door, I will come into him and sup with him and he with me." Rev. 3:20

Jesus at the Door – "Behold, I stand at the door, and knock... and if any hear my voice and will open the door, I will come into him and sup with him and he with me." Rev. 3:20 Jesus Heals a Leper. Jesus stretched out his hand and touched him, saying, "Be clean," and his leprosy was cured immediately. Matthew 8:3

Jesus Heals a Leper. Jesus stretched out his hand and touched him, saying, "Be clean," and his leprosy was cured immediately. Matthew 8:3 Christ Leaving His Mother – This window, made in 1966, replaced the window damaged in the fire of 1965.

Christ Leaving His Mother – This window, made in 1966, replaced the window damaged in the fire of 1965.

The Resurrected Jesus and the Two Marys

The Resurrected Jesus and the Two Marys

References

- ↑ Shealy, George B., Gen. John A. Wagener: Charleston and South Carolina's Foremost German American. Alexander's Office Supply, Walhalla, SC, 2000. pg 58.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "John A. Wagener Monument Historical Marker".

- ↑ "Find A Grave: Hampstedt Cemetery". www.findagrave.com.

- ↑ Poston, J.H., The Buildings of Charleston, University of SC Press, 1997, pg. 346.

- ↑ Poston, Jonathan, The Buildings of Charleston, pg.469 1997. ISBN 1-57003-202-5

- 1 2 3 St. Matthew's Evangelical Lutheran Church: 125 Years of Christian Service, 1967.

- ↑ How the Germans Became White Southerners: German Immigrants and African Americans in Charleston, South Carolina, 1860-1880. Jeffery Strickland, Journal of American Ethnic History, Fall 2008, Vol 28, No. 1.

- ↑ "St. Johannes Lutheran Church of Charleston, SC: History of the Church". Archived from the original on December 1, 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2011.

- ↑ "The New German Church". Daily News. Charleston, South Carolina. July 3, 1867. p. 3. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Page Not Found".

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ↑ "World War II POW Camp Historical Marker".

- ↑ St. Matthew's Lutheran Church: 125 Years of Christian Service, 1967.

- 1 2 "Opus List, Austin Organs" (PDF). Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ↑ The Windows of St. Matthew's Lutheran Church Charleston, SC. Leaflet, 2010.

- ↑ Rev. Dr. Richard R. Campbell Sr., First hand account by the Senior Pastor of St. Matthew's in 1989, Oct 24, 2011.

- ↑ "Charleston, 1884 May:: Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps". digital.tcl.sc.edu.

- ↑ "53. St. Matthew's German Lutheran Church". Charleston Walking Tours, Key to the City. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ↑ "St. Matthew's German Lutheran Church, 405 King St". Charleston Public Library. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ↑ Legerton, Clifford L; Lilly, Edward G., Editor (1966). Historic Churches of Charleston (Hardcover). Charleston: Legerton & Co. pp. 40–41.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Ravenel, Beatrice St. Julien (1904–1990); Julien, Carl (photographs); Carolina Art Association (1992). Architects of Charleston. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 265–266. ISBN 0-87249-828-X. LCCN 91034126. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Stoney, Samuel Gaillard (1960). This is Charleston: a survey of the architectural heritage of a unique American city. Carolina Art Association. p. 65.

- ↑ "South Carolina State House". Archived from the original on February 1, 2011. Retrieved February 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Charleston Historic District". National Register Historic Properties in South Carolina. South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

Further reading

- "Charleston Historic Religious and Community Buildings". National Park Service. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- Hudgins; Carter L., ed (1994). The Vernacular Architecture of Charleston and the Lowcountry, 1670 – 1990. Charleston, South Carolina: Historic Charleston Foundation.

{{cite book}}:|last2=has generic name (help) - Jacoby, Mary Moore, ed. (1994). The Churches of Charleston and the Lowcountry (hardback). Columbia South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-888-3. ISBN 978-0-87249-888-4.

- Legerton, Clifford L; Lilly, Edward G., Editor (1966). Historic Churches of Charleston (Hardcover). Charleston: Legerton & Co. pp. 140–141.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Moore, Margaret H (1997). Complete Charleston: A Guide to the Architecture, History, and Gardens of Charleston. Charleston, South Carolina: TM Photography. ISBN 0-9660144-0-5.

- Poston, Jonathan H (1997). The Buildings of Charleston: A Guide to the City's Architecture (hardcover). Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-202-5. ISBN 1-57003-202-5

- Ravenel, Beatrice St. Julien (1904–1990); Julien, Carl (photographs); Carolina Art Association (1992). Architects of Charleston. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-828-X. LCCN 91034126. Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Severens, Kenneth (1988). Charleston Antebellum Architecture and Civic Destiny (hardback). Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0-87049-555-0. ISBN 978-0-87049-555-7

- Smith, Alice R. Huger; Smith, D.E. Huger (1917). Dwelling Houses of Charleston, South Carolina. New York: Diadem Books.

- Stockton, Robert; et al. (1985). Information for Guides of Historic Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston, South Carolina: City of Charleston Tourism Commission.

- Waddell, Gene (2003). Charleston Architecture, 1670-1860 (hardback). Vol. 2. Charleston: Wyrick & Company. p. 992. ISBN 978-0-941711-68-5. ISBN 0-941711-68-4

- Wells, John E.; Dalton, Robert E. (1992). The South Carolina architects, 1885–1935: a biographical dictionary. Richmond, Virginia: New South Architectural Press. ISBN 1-882595-00-9.

- Whitelaw, Robert N. S.; Levkoff, Alice F. (1976). Charleston, come hell or high water: a history in photographs. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. p. 89.

- Weyeneth, Robert R. (2000). Historic Preservation for a Living City: Historic Charleston Foundation, 1947-1997. University of South Carolina Press. p. 256. ISBN 1-57003-353-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) ISBN 978-1-57003-353-7.