Paulinus | |

|---|---|

| Bishop of York | |

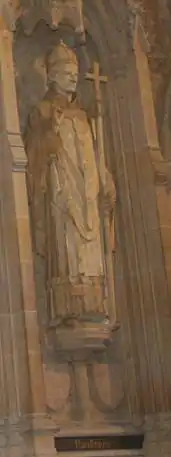

Statue at Rochester Cathedral | |

| Appointed | 627 |

| Term ended | 633 |

| Predecessor | Founder |

| Successor | Chad |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 21 July 625 by Justus |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 10 October 644 Rochester, Kent |

| Buried | Rochester Cathedral |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 10 October |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church, Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Communion |

Paulinus[lower-alpha 1] (died 10 October 644) was a Roman missionary and the first Bishop of York.[lower-alpha 2] A member of the Gregorian mission sent in 601 by Pope Gregory I to Christianize the Anglo-Saxons from their native Anglo-Saxon paganism, Paulinus arrived in England by 604 with the second missionary group. Little is known of Paulinus's activities in the following two decades.

After some years spent in Kent, perhaps in 625, Paulinus was consecrated a bishop. He accompanied Æthelburg of Kent, sister of King Eadbald of Kent, on her journey to Northumbria to marry King Edwin of Northumbria, and eventually succeeded in converting Edwin to Christianity. Paulinus also converted many of Edwin's subjects and built some churches. One of the women Paulinus baptised was a future saint, Hilda of Whitby.

Following Edwin's death in 633, Paulinus and Æthelburg fled Northumbria, leaving behind a member of Paulinus's clergy, James the Deacon. Paulinus returned to Kent, where he became Bishop of Rochester. He received a pallium from the pope, symbolizing his appointment as Archbishop of York, but too late to be effective. After his death in 644, Paulinus was canonized as a saint and is now venerated in the Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Anglican Churches.

Early life

Paulinus was a monk from Rome sent to the Kingdom of Kent by Pope Gregory I in 601, along with Mellitus and others, as part of the second group of missionaries sent to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. He was probably an Italian by birth.[2] The second group of missionaries arrived in Kent by 604, but little is known of Paulinus's further activities until he went to Northumbria.[2]

Paulinus remained in Kent until 625, when he was consecrated as bishop by Justus, the Archbishop of Canterbury, on 21 July.[3] He then accompanied Æthelburg, the sister of King Eadbald of Kent, to Northumbria where she was to marry King Edwin of Northumbria. A condition of the marriage was that Edwin had promised that he would allow Æthelburg to remain a Christian and worship as she chose. Bede, writing in the early 8th century, reports that Paulinus wished to convert the Northumbrians, as well as provide religious services to the new queen.[2]

There is some difficulty with Bede's chronology on the date of Æthelburh's marriage, as surviving papal letters to Edwin urging him to convert imply that Eadbald only recently had become a Christian, which conflicts with Bede's chronology. The historian D. P. Kirby argues that Paulinus and Æthelburh must therefore have gone to Northumbria earlier than 624, and that Paulinus went north, not as a bishop, but as a priest, returning later to be consecrated.[4] The historian Henry Mayr-Harting agrees with Kirby's reasoning.[5] Another historian, Peter Hunter Blair, argues that Æthelburh and Edwin were married before 625, but that she did not go to Northumbria until 625.[4] If Kirby's arguments are accepted, then the date of Paulinus's consecration needs to be changed by a year, to 21 July 626.[6]

Bede describes Paulinus as "a man tall of stature, a little stooping, with black hair and a thin face, a hooked and thin nose, his aspect both venerable and awe-inspiring".[7]

Bishop of York

Bede relates that Paulinus told Edwin that the birth of his and Æthelburg's daughter at Easter 626 was because of Paulinus's prayers. The birth coincided with a foiled assassination attempt on the king by a group of West Saxons from Wessex. Edwin promised to convert to Christianity and allow his new daughter Eanflæd to be baptised if he won a victory over Wessex. He did not fulfill his promise immediately after his subsequent military success against the West Saxons however, only converting after Paulinus had revealed the details of a dream the king had before he took the throne, during his exile at the court of King Rædwald of East Anglia. In this dream, according to Bede, a stranger told Edwin that power would be his in the future when someone laid a hand on his head. As Paulinus was revealing the dream to Edwin, he laid his hand on the king's head, which was the proof Edwin needed. A late seventh-century hagiography of Pope Gregory I claims that Paulinus was the stranger in the vision;[2] if true, it might suggest that Paulinus spent some time at Rædwald's court,[8] although Bede does not mention any such visit.[2]

It is unlikely that supernatural affairs and Paulinus's persuasion alone caused Edwin to convert. The Northumbrian nobles seem to have been willing and the king also received letters from Pope Boniface V urging his conversion.[2] Eventually convinced, Edwin and many of his followers were baptised at York in 627.[9] One story relates that during a stay with Edwin and Æthelburg at their palace in Yeavering, Paulinus spent 36 days baptising new converts.[9] Paulinus also was an active missionary in Lindsey,[10] and his missionary activities help show the limits of Edwin's royal authority.[11]

Pope Gregory's plan had been that York would be England's second metropolitan see, so Paulinus established his church there.[9] Although built of stone, no trace of it has been found.[2] Paulinus also built several churches on royal estates.[12] His church in Lincoln has been identified with the earliest building phase of the church of St Paul in the Bail.[2]

Among those baptised by Paulinus were Hilda, later the founding abbess of Whitby Abbey,[13] and Hilda's successor, Eanflæd, Edwin's daughter.[14] As the only Roman bishop in England, Paulinus also consecrated another Gregorian missionary, Honorius, as Archbishop of Canterbury after Justus' death, sometime between 628 and 631.[2]

Bishop of Rochester

Edwin was defeated by an alliance of Gwynedd Welsh and Mercian Angles, being killed at the Battle of Hatfield Chase, on a date traditionally given as 12 October 633.[2] One problem with the dating of the battle is that Pope Honorius I wrote in June 634 to Paulinus and Archbishop Honorius saying that he was sending a pallium, the symbol of an archbishop's authority, to each of them.[15] The pope's letter shows no hint that news of Edwin's death had reached Rome, almost nine months after the supposed date of the battle. The historian D. P. Kirby argues that this lack of awareness makes it more likely that the battle occurred in 634.[15]

Edwin's defeat and death caused his kingdom to fragment into at least two parts.[2] It also led to a sharp decline in Christianity in Northumbria[16] when Edwin's immediate successors reverted to paganism.[2] Widowed queen Æthelburg fled to her brother Eadbald's Kent kingdom. Paulinus went with her, along with Edwin and Æthelburg's son, daughter, and grandson. The two boys went to the continent for safety, to the court of King Dagobert I. Æthelburg, Eanflæd, and Paulinus remained in Kent, where Paulinus was offered the see, or bishopric, of Rochester, which he held until his death. Because the pallium did not reach Paulinus until after he had left York, it was of no use to him.[2] Paulinus's deputy, James the Deacon, remained in the north and struggled to rebuild the Roman mission.[16]

Death and veneration

Paulinus died on 10 October 644 at Rochester,[17][lower-alpha 3] where he was buried in the sacristy of the church.[18] His successor at Rochester was Ithamar, the first Englishman consecrated to a Gregorian missionary see.[19] After Paulinus's death, Paulinus was revered as a saint, with a feast day on 10 October. When a new church was constructed at Rochester in the 1080s his relics, or remains, were translated (ritually moved) to a new shrine.[2] There also were shrines to Paulinus at Canterbury, and at least five churches were dedicated to him.[20] Although Rochester held some of Paulinus's relics, the promotion of his cult there appears to have occurred after the Norman Conquest.[21] He is considered a saint by the Roman Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, and the Eastern Orthodox Church.[22][23]

Paulinus's missionary efforts are difficult to evaluate. Bede implies that the mission in Northumbria was successful, but there is little supporting evidence, and it is more likely that Paulinus's missionary efforts there were relatively ineffectual. Although Osric, one of Edwin's successors, was converted to Christianity by Paulinus, he returned to paganism after Edwin's death. Hilda, however, remained a Christian, and eventually went on to become abbess of the influential Whitby Abbey.[2] Northumbria's conversion to Christianity was mainly achieved by Irish missionaries brought into the region by Edwin's eventual successor, Oswald.[24]

See also

Notes

Citations

- ↑ Lapidge "Ecgbert" Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Costambeys "Paulinus (St Paulinus)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ↑ Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 224

- 1 2 Kirby Earliest English Kings pp. 33–34

- ↑ Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 66

- 1 2 Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 206 footnote 2

- ↑ Quoted in Blair World of Bede p. 95

- ↑ Yorke Kings and Kingdoms p. 28

- 1 2 3 Lapidge "Paulinus" Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England

- ↑ Stenton Anglo-Saxon England pp. 115–116

- ↑ Williams Kingship and Government p. 17

- ↑ Yorke Conversion of Britain p. 161

- ↑ Blair World of Bede p. 147

- ↑ Blair World of Bede p. 149

- 1 2 Kirby Earliest English Kings p. 56

- 1 2 Stenton Anglo-Saxon England p. 116

- ↑ Fryde, et al. Handbook of British Chronology p. 221

- ↑ Blair World of Bede pp. 97–98

- ↑ Sharpe "Naming of Bishop Ithamar" English Historical Journal p. 889

- ↑ Farmer Oxford Dictionary of Saints p. 418

- ↑ Rollason "Shrines of Saints" Archaeology Data Services

- ↑ Holford-Stevens and Blackburn Oxford Book of Days p. 409

- ↑ Walsh Dictionary of Saints p. 475

- ↑ Mayr-Harting Coming of Christianity p. 68

References

- Blair, Peter Hunter (1990). The World of Bede (Reprint of 1970 ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39819-3.

- Costambeys, Marios (2004). "Paulinus (St Paulinus) (d. 644)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (October 2005 revised ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21626. Retrieved 6 March 2009. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Farmer, David Hugh (2004). Oxford Dictionary of Saints (Fifth ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860949-0.

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1996). Handbook of British Chronology (Third revised ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-24211-8.

- Lapidge, Michael (2001). "Ecgberht". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Lapidge, Michael (2001). "Paulinus". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (1991). The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-00769-9.

- Rollason, David. "The Shrines of Saints in later Anglo-Saxon England: Distribution and Significance" (PDF). Archaeology Data Services. Department of Archaeology, University of York. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- Sharpe, R. (September 2002). "The Naming of Bishop Ithamar". The English Historical Review. 117 (473): 889–894. doi:10.1093/ehr/117.473.889. JSTOR 3489611. S2CID 159918370.

- Stenton, F. M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Walsh, Michael J. (2007). A New Dictionary of Saints: East and West. London: Burns & Oats. ISBN 978-0-86012-438-2.

- Williams, Ann (1999). Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England c. 500–1066. London: MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-56797-8.

- Yorke, Barbara (2006). The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c. 600–800. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-77292-3.

- Yorke, Barbara (1997). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16639-X.

Further reading

- Hunt, William (1895). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 44. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Mayr-Harting, H. M. R. E. (1967). "Paulinus of York". In G. J. Cuming (ed.). Studies in Church History IV: The Province of York. Leiden: Brill. pp. 15–21.

External links

- Paulinus 1 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England – listing of most contemporary and close to contemporary mentions of Paulinus in the primary sources. Includes some spurious charter listings.