St. Peter's Church | |

| |

| |

| Location | Southeast of Queenstown on U.S. Route 50, Queenstown, Maryland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°58′41″N 76°8′3″W / 38.97806°N 76.13417°W |

| Area | 1.5 acres (0.61 ha) |

| Built | 1823-1827 |

| Architectural style | Victorian Gothic |

| NRHP reference No. | 80001833[1] |

St. Peter's Church, also known as the Church of St. Peter the Apostle, is a nearly 200-years-old Roman Catholic church located in Maryland's Eastern Shore near Queenstown. It is a prominent landmark along U.S. Route 50 in Maryland, which is part of the main route from Washington and Baltimore to Atlantic beach resort towns in Maryland and Delaware.

Catholics came to Kent Island around 1639, and moved to what became the Queenstown area shortly afterwards. They originally practiced their religion discreetly in their homes. The parish of St. Peter's was established in 1765, and the original chapel was constructed some time in the next 20 years. This was the third permanent mission on Maryland's Eastern Shore. Construction of the present church began in 1823 and was completed in 1827. The building was expanded in 1877 after fundraisers were unable to raise enough money to build a completely new building in town. A portion of the church's exterior shell is the only part remaining from the 1827 structure.

The church, which is built in the Victorian-Gothic style, has a steep roof and rose windows, and is located very near to the road. The interior is mostly the same as it was in the 1877 Victorian construction period, and contains all of the stained glass and altar furniture from that period. The church was placed in the National Register of Historic Places on March 10, 1980.

Geography and setting

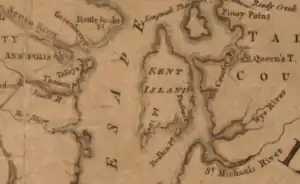

St. Peter's Church is located 1.5 miles (2.4 km) south of Queenstown, Maryland.[2] The region is part of a large peninsula that separates the Chesapeake Bay from the Atlantic Ocean. The peninsula, which contains the entire state of Delaware and the eastern shores of Maryland and Virginia, is often called the Delmarva Peninsula.[3] Nearby Kent Island is the location of the first permanent European settlement in what is now Maryland, and it was established in 1631.[4] The church is positioned a few steps from the road on the north side of U.S. Route 50. Although the immediate area around the church is rural, Route 50 can have considerable traffic during the summer as travelers from the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area use the road to get to Atlantic coast summer resort destinations such as Maryland's Ocean City and several beaches in Delaware.[5][6]

Although Catholicism was the dominant religion for Spanish and French possessions in the colonial Americas, Catholics were "an insignificant minority in a state of practical outlawry" in the 13 English colonies.[7] Prior to the American Revolution, Catholic church and school buildings in the English American colonies were prohibited except in Pennsylvania.[8] The Maryland colony was unique in English colonization because of its attempt to have Catholics and Protestants live together as equals.[9] This attempt had some significant failures.[Note 1]

Catholics arrived at Maryland's Eastern Shore on Kent Island around 1639. They are thought to have moved from Kent Island to what became Queenstown during the 1640s, possibly during a conflict between Lord Baltimore (a Catholic) and William Claiborne (a Protestant) over control of the island.[12] During this time, the region around Queenstown north to Piney Point and south to the area along the Wye River (including communities that became Morgan's Neck and Wye Neck) became populated mostly by Roman Catholic land owners.[13] Continuing to practice their religion discreetly, Catholic families in the area typically used a room in their house as a chapel room.[14]

Establishment of St. Peter's

The parish of St. Peter's was established in 1765.[Note 2] The chapel, which was constructed some time before 1784, was the third permanent mission on Maryland's Eastern Shore.[2] In 1765, Reverend Joseph Mosley was pastor at nearby St. Joseph's (the second permanent mission) in Talbot County and ministered to five regular mission stations in the area in addition to St. Joseph's.[16] Over time, he came to do more work in Queen Anne's County, and Queenstown became his "chief congregation". He was succeeded by Father John Bolton in 1787.[17]

Construction

In 1760, Edward Neale of Bowlingly died, and his will provided for two daughters and other family members. It also left "the sum of 50 pounds" for a Catholic clergyman to purchase land nearby so he "may live convenient to the congregation".[15] Bowlingly was adjacent to the village of Queenstown. Catholic leaders purchased 1.5 acres (0.61 ha) of land from Edward Rogers for the price of 28 pounds.[18] The land was located about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from Queenstown along the road to Easton and Wye Mills.[15] A surviving baptismal register kept by Mosley shows that the original church was already built in 1784, but no records remain that list the exact year construction was completed.[19] This small structure looked more like a house than a church.[2] In 1819, Archbishop Marechal described this church as “a most miserable old house”, and it was too small for its congregation.[18]

New church

In the early 1820s, the parrish was again the beneficiary of generous provisions in the wills of its members. These donations enabled Reverend James Moynihan to begin preparations for construction of a new church in 1823.[20] During this time, Moynihan had health issues and was replaced by Reverend Peter Veulemans, who became the first resident priest at St. Peters.[21] The new building was 45 feet long by 30 feet wide, and made of brick. After construction of the new church was completed in 1827, the old structure was converted to a parsonage that lasted until it was demolished in 1960.[2]

Today's church

By 1868, Bishop Becker of the Diocese of Wilmington described all seven of the Catholic churches in Maryland's Eastern Shore as “old and wretched”.[22] In 1869, Reverend Edward Henchy made plans to build a new church, with a rectory and resident pastor, in downtown Queenstown. Festivals and tournaments were held to raise money. However, fundraising for the new church was not as successful as hoped. In 1877, church leadership decided to expand the current church instead of building an entirely new one in Queenstown.[23] Materials were brought close to the site by boat, and the contractor was John Stack of Baltimore.[24] Costs were $5,000 (equivalent to $137,406 in 2022) to $6,000 (equivalent to $164,888 in 2022).[24]

The expanded version of the church kept some of the brick walls from the 1820s church. An estimated 2,000 people attended a dedication ceremony held on December 23, 1877.[24] This church is basically the church that stands today. A brick sacristy and meeting room were added to the northeast side during the 1960s.[2]

Renovations and additions

For the next 100 years, the church received various upgrades and improvements. During the 1930s, the cemetery was leveled, restored, and seeded with grass.[25] During the 1930s and 1940s, Reverend Francis J. Fisher was responsible for replacing a cast iron stove with an oil burning furnace and electrifying the church.[26]

During the 1950s the State Roads Commission made plans to widen U.S. Route 50 and condemned the church to be torn down. An appeal saved the church when it was agreed that the church would build a brick wall between the road and the church.[27] Members of the Friel family were involved with the wall's funding and design. They were also later involved with extensions of the wall along the sides of the church.[28]

By 1959, it was decided that the old rectory was a fire hazard and would be torn down. Two additions on the site of the old rectory were completed in 1967: a sacristy and a meeting room. The children of Helena Green Raskob provided funding for the meeting room, and it was named the Raskob Memorial Room in her honor. Members of the Friel family were involved with the new sacristy. The designers of the additions were James R. Friel and architect John Walton.[29] During the 1970s, the church was refurbished and air conditioning was added.[30]

Description

Henchy is credited as the designer of the 1877 church. The 1820s church was changed from a rectangle to a cruciform by adding a nave on one side of the original structure and projecting an apse on the other. The interior ceiling was raised to be about double its original height.[31] Various local families helped with renovations by providing either labor or transportation of materials. The rose windows were donated by Nannie Willson and designed by Katie Bordley.[31]

Church exterior

The church building is made of brick and uses portions of the 1820s church exterior walls.[2] The most noticeable exterior features are the steep slate roofs; large rose windows in the east, north, and west gables; a Victorian bell cupola on the south side closest to the road; and Victorian-Gothic vergeboards on the projecting gables of the roof.[2] In a newspaper article describing the dedication ceremony, it was mentioned that the "exquisitely toned bell" could be heard 1.5 miles (2.4 km) away in Queenstown.[24]

Church interior

The church interior, using the cruciform plan, has a nave, a transept, and an apse.[2] One enters the nave from a small vestibule (also known as a narthex) on the south side. A central aisle, with pews on each side, runs through the nave, ending at the walnut communion rail. A gallery supported by chamfered pillars is located at the back of the nave. The transept is what remains from the 1820s church. At each end of the transept is a rose window with two windows below it—all containing original stained glass. The apse is octagonal and contains the altar.[2] A newspaper article describing discussing the dedication ceremony described the altar as "variegated marble, chiseled into quaint and beautiful designs".[24] The door to the left of the altar leads to a small confessional, while the door to the right leads to the sacristy constructed in the 1960s. Much of the interior woodwork is from the 1877 expansion. Several pews in the gallery are from the 1820s church. The paneled wainscoting was added during a 1927 centennial celebration, and is made to look similar to the 1877 gallery railing. All stained glass and altar furniture is from 1877.[2]

Cemetery

Over 300 people are buried at St. Peter's Cemetery. Not all burial sites are marked by tombstones, but they are listed in parish records.[32] The oldest grave is for Joseph King, who died in 1820. His gravestone is located close to a tall boxwood shrub.[33] Reverend Henchy, who died in 1895, is also buried in the cemetery. His gravestone says "Pastor of the church for 20 years".[34]

Current use

The St. Peter's Church in Queenstown is one of two churches that are part of the same parish. The other church, Our Mother of Sorrows, is located less than 10 miles away in Centreville, Maryland.[35] The parish has about 620 families. It has a wide range of ministries, including religious education and hospitality programs.[35] Mass times at St. Peter's are 5:30 pm on Saturdays and 7:30 am on Sundays.[36] In 2019, the church received donations that enabled it to begin refurbishing the structure's windows, and more work is expected to be done on the building's exterior.[37][38]

National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form for the church was prepared on April 28, 1978.[2] The form's statement of significance begins with "St. Peter's Church has played an important role in the history the Roman Catholic Church in Maryland. A Catholic community was established in this area soon after Claiborne founded his colony on Kent Island in 1631, and this group, with the communities in St. Mary's and Charles Counties, formed the earliest enclave of Catholicism in the American colonies."[2] The church was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on March 10, 1980.[39]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ The first major failure for Catholics and Protestants to live together in Maryland was a lawless period during 1644–1646 known as the Plundering Time, where militant Protestants caused the Catholic governor of Maryland to flee to Virginia and the houses of Catholic leaders were plundered.[10] Catholic leaders Andrew White and Thomas Copley were captured by Protestant forces and sent in chains to England because they refused to swear loyalty to the Church of England.[11]

- ↑ One author discussing St. Peter's says "there is some reason to believe that it was originally called St. Mary's".[15]

Citations

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Ridout, Orlando (Queen Anne's County Historical Society) (1978). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: St. Peter's Church" (PDF). National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior (Maryland Historical Trust). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ↑ Ayres Jr., B. Drummond (September 12, 1982). "Delmarva: The Island on a Peninsula". New York Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ↑ "History of Kent Island". The Kent Island Heritage Society. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ↑ "William Preston Lane Jr. Memorial (Bay) Bridge (US 50/301)". Maryland Transportation Authority (MDTA). Archived from the original on August 13, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ↑ "Opinion: Expanding the Bay Bridge is a Responsible Thing to Do". MarylandReporter.com. September 8, 2016. Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 8, 2019.

- ↑ Ellis 1969, p. 41

- ↑ Kornwolf 2002, p. 1433

- ↑ Ellis 1969, p. 25

- ↑ Smith 1901, pp. 115–116

- ↑ Shea 1886, pp. 62–63

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 132

- ↑ Carley 1976, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 12

- 1 2 3 Carley 1976, p. 26

- ↑ Carley 1976, pp. 27–28

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 39

- 1 2 Carley 1976, p. 58

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 29

- ↑ Carley 1976, pp. 60–61

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 63

- ↑ Catholic Editing Company 1914, p. 215

- ↑ Carley 1976, pp. 96–97

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carley 1976, p. 98

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 109

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 110

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 111

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 113

- ↑ Carley 1976, pp. 114–115

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 118

- 1 2 Carley 1976, p. 100

- ↑ Carley 1976, pp. 142–144

- ↑ Carley 1976, pp. 145–146

- ↑ Carley 1976, p. 144

- 1 2 Morton, Gary (December 11, 2015). "Our Mother of Sorrows/St. Peter's: Celebrating 250 Years in Queen Anne's County, Maryland". The Dialog. p. 1. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Our Mother of Sorrows / St Peter's". Our Mother of Sorrows / St Peter the Apostle. Archived from the original on July 5, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ↑ Jaime, Kristian (July 24, 2019). "Queenstown Church Receives Landmark Donation". Cecil Whig. B. Rae Perryman. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ↑ Jaime, Kristian (July 5, 2019). "Queenstown Church Continues Renovations". Kent Island Bay Times and Record Observer. My Eastern Shore, Maryland. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ↑ American Association for State and Local History, United States National Park Service & National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers 1994, p. 333

References

- American Association for State and Local History; United States National Park Service; National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers (1994). National Register of Historic Places, 1966–1994 : Cumulative List Through January 1, 1994. Washington, DC: National Park Service: The Preservation Press, National Trust for Historic Preservation: National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers. OCLC 40135121.

- Carley, Edward B. (1976). The Origins and History of St. Peter's Church, Queenstown, Maryland, 1637-1976. Centreville, Maryland: Carley. OCLC 3710042.

- Catholic Editing Company (1914). The Catholic Church in the United States of America, Undertaken to Celebrate the Golden Jubilee of His Holiness, Pope Pius X. Volume III. New York: Catholic Editing Company. OCLC 3457280.

- Ellis, John Tracy (1969). American Catholicism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 1088156374.

- Kornwolf, James D. (2002). Architecture and Town Planning in Colonial North America Volume 3. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. OCLC 314254072.

- Shea, John Gilmary (1886). The Catholic Church in Colonial Days. New York: J. G. Shea. OCLC 423601980.

- Smith, Helen Ainslie (1901). The Thirteen Colonies. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 3824907.