| St John's Cathedral | |

|---|---|

St John's Cathedral | |

St John's Cathedral | |

| 33°48′57″S 151°00′09″E / 33.8159°S 151.0026°E | |

| Location | Hunter Street, Parramatta, New South Wales |

| Country | Australia |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| History | |

| Status | Regional Cathedral |

| Founded | 5 April 1797 |

| Founder(s) | Governor John Hunter |

| Dedication | St John, in honour of Governor Hunter |

| Dedicated | 10 April 1803 by Rev. Samuel Marsden |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | |

| Specifications | |

| Number of spires | 2 |

| Bells | 13 (hung in 1923) |

| Administration | |

| Province | New South Wales |

| Diocese | Sydney |

| Parish | Parramatta |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | Rev Canon Bruce Morrison |

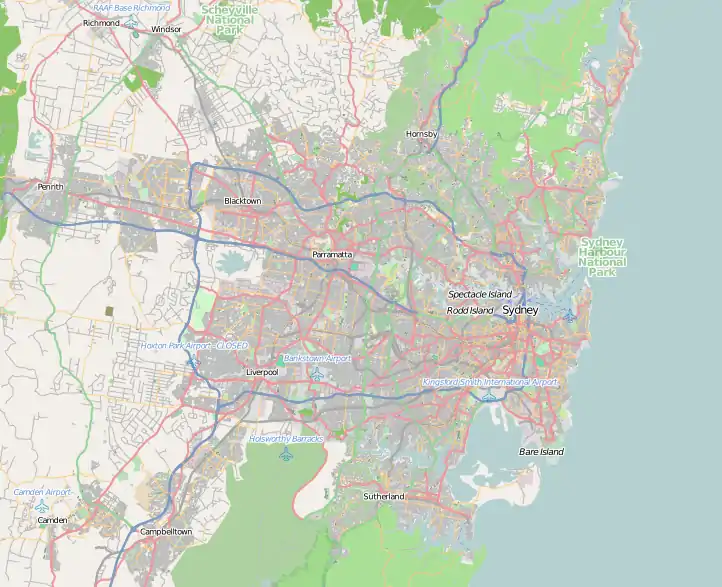

St John's Cathedral is a heritage-listed, Anglican cathedral in Parramatta, City of Parramatta, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. St John's was given the status of provisional cathedral of the Anglican Diocese of Sydney in 1969, and designated a Regional Cathedral in 2011 for the Western Region.[1] It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 5 March 2010.[2]

The current rector is Reverend Canon Bruce Morrison.

History

St John's Cathedral is located near Parramatta railway station and is the oldest church site in Australia in continuous use. In October 1788, soon after the first load of convicts arrived at Sydney Cove, Governor Arthur Phillip took a trip up to find the head of the Sydney Harbour (Port Jackson). Finding inhabitable land there he formed a settlement at Rose Hill (named after Sir George Rose the Under-Secretary of the Treasurer) and mapped out the bare bones of a town that extended from the foot of Rose Hill for one mile eastward along the creek.[3] This place he named Parramatta as this was his interpretation of the name given by the first peoples to the spot on which the town is situated.

The Chaplain of the First Fleet, Reverend Richard Johnson, conducted the first Christian worship in Parramatta on 28 December 1788. Johnson visited Parramatta fortnightly and held services under a tree on the river bank near the present day ferry terminal at the end of Smith Street. The service on Christmas Day 1791 was held in a carpenter's shop near Governor Phillip's residence in Parramatta.[4] By then, there were one thousand people living in the district and being ministered by Reverend Johnson.

In a letter to Governor Phillip dated 23 March 1792, Johnson states: "Last spring there was the foundation of a church laid a Parramatta. Before it was finished it was converted into a gaol or lock up house, and now it is converted into a granary. … I go up to Parramatta, as usual, once a fortnight the distance by water about fourteen miles."[5]

On 10 March 1794, the Reverend Samuel Marsden, who had been appointed Assistant Chaplain, arrived in Parramatta and relieved Johnson of the care of these Western settlements.[6]

The first timber church

In 1796 Marsden dedicated a makeshift building of two old timber huts at the corner of George and Marsden Streets (the site of the present-day Woolpack Hotel) as the first church building in the settlement. In a letter dated 17 September 1796 at Parramatta, Marsden wrote, "A convict hut is almost now ready for me to preach in at Parramatta, the first building of any kind that has ever been appropriated for that sacred use here since I came to the Colony."[7]: 32–33

On 14 September 1798, Marsden wrote about his first service in this church, attended by twelve worshippers.[8] This reference has caused confusion to historians due to an editor's note (most likely erroneous) which states that this temporary church was "Built where St John's now stands."[8]

In his book In Old Australia: Records and Reminiscences from 1794, Reverend James Samuel Hassall twice mentions the old timber church: "There had been a church, built of timber, at the corner of George and Macquarie (sic) Streets, but it was gone in my time, and a Court-house built upon the site..."[9] and "At Parramatta, the services were held in a carpenter's shop or in the open air, until, on the first Friday in August, 1796, Mr. Marsden opened a church built out of the materials of two old huts. This temporary place of worship stood at the corner of George and Marsden streets."[10]

The Rev. James Samuel Hassall was born in Parramatta in 1823 and lived there during his childhood, being educated at The King's School. He was the eldest son of Rev. Thomas Hassall (1794-1868) and a grandson of Rev. Samuel Marsden (died 1838). Both James Hassall's father and grandfather were in Parramatta during its earliest days and undoubtedly James would have heard about these early times from them both. Hassall's first reference to the old church is a little confused. The streets aren't named correctly, with George and Macquarie Streets being parallel rather than intersecting. The second quotation correctly places the building at the corner of George and Marsden Streets. However Hassall's mention of a court house being on the site is not correct. From 1796 to 1895 the Woolpack Hotel and it predecessors stood on the north-east block at the corner of George and Marsden Streets so it is not possible that Marsden's timber church was on this site – it was already occupied by the hotel. This was the land, and not the church site, that was sold to the Crown in 1895 and a Court House built. The timber church was located across George Street on the south-east corner of the intersection, in fact where the hotel that bears the name Woolpack stands today. A convict hut was on this block in 1792 and part of this block was leased to the Rev. Samuel Marsden. It was on this site, and in this crude converted hut, that services were conducted Sunday by Sunday at Parramatta from September 1796 until Easter Day 1803 when the first St. John's Church was opened about 350 metres (1,148 ft) away at, what was then, the southern end of Church Street.

A church of brick and stone

Governor John Hunter was a religious man and was concerned that there were no proper churches.[11] On 1 November 1798, Hunter reported he had laid the foundation of a small church at Parramatta.[12] It was later claimed that the foundation stone of St John's, the first brick church in Australia, was laid on 5 April 1797.[10]

Foundations were also laid for a stone church at Sydney to measure 46 metres (150 ft) long and 16 metres (52 ft) wide. Preparations for "making a similar building at Parramatta of smaller dimensions" were reported.[13] A Return of Public Works since October 1796 showed that by 25 September 1800, Hunter had "Erected an elegant church at Parramatta one hundred feet length and forty-four feet in width, with a room of twenty feet long raised on stone pillars intended for a vestry or council room."[14] The Church was open but not complete in 1800. Work proceeded slowly, so when a number of "glaring untruths" were published by "some persons in the Colony for sinister ends,"[15] apparently including the suggestion that there was already a church in Sydney, Governor King was prompted to set the record straight in a letter to Sir Joseph Banks on 21 August 1801: "Nor have we an Elegant stone Church built at Sydney…- one of brick and stone will be finished in the course of the year at Parramatta and the foundation of one at Sydney is just begun."[15]

In 1802, David Collins published a "Plan & Elevation of a Church Built at Parramatta [sic] New South Wales during the Government of John Hunter Esqr 1800."[13]

Governor King proclaimed the two first parishes in the colony on 23 July 1802 being St Phillip's, Sydney and St John's, Parramatta. On 9 November 1802 he declared that the church being built at Parramatta would be named as St John in honour of the former governor, John Hunter.[16] The new St John's was opened on 10 April 1803 when Reverend Marsden performed Divine Service for the first time, with a service based on 2 Chronicles c. 6 v.18.[17] The church was described as being sizeable, handsome and well finished though the pews were to yet to be installed. The original Church was stuccoed brick and was more than likely built by convict labourers.[18]

Governor King reported on 1 March 1804 that when he took control the church at Parramatta "was just covering in" [i.e. being roofed] but was now complete.[19] A sketch of the Parramatta Church in the Banks Papers from 1807 apparently sent by Governor Bligh was inscribed "Parramatta Church, built of brick and in a very bad state; unfinished in the inside – Stands in a Swamp."[20] The last notation may explain why there were problems with the stability of the church. Construction of a brick barrel drain from the 1820s onwards from the market place opposite the church (now the site of Parramatta Town Hall) to the river greatly improved the drainage of this vicinity.[21] Continuing problems with the church were reported over the next few years.[22]

Andrew Houison claimed that the vestry fell down though did not know when this occurred.[23] No other reference to this event can be found but, on 1 August 1810, Governor Macquarie instructed Lieutenant Durie, commandant at Parramatta, to detail Richard Rouse to make temporary repairs to the church, as directed by Marsden, that could be completed "with little labour and Expense."[24] Durie instructed Rouse to do this within the next few days.[25] In 1812, James Harrax was paid £110 for "Repairs" to the church.[26] From 1 October to 31 December 1813, repairs to St John's to the value of £431/3/4 were completed.[27]

Early nineteenth century alterations

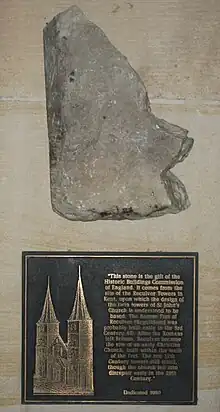

Between 1817 and 1819, a facade incorporating twin towers topped with spires was added at the western end where the vestry had been. Made out of brick, the facade, towers and spires were copied from those of St Mary's Church, Reculver, in Kent, England: that church was founded in the 7th century, the towers were added in the 12th, and the spires by the early 15th. A campaign to save St Mary's Church was raging when the Macquaries left England.[28] Elizabeth Macquarie showed Lieutenant John Cliffe Watts, aide-de-camp of the 46th Regiment, a watercolour of the church at Reculver and asked him to design some towers for St. John’s.[29]

In an article in the Parramatta Historical Society Journal, Frank Walker refers to Watts’s drawing folder held in the State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, which includes drawings of the towers and spires; one of the drawings bears the watermark of 1813 and has Macquarie's initials written on it.[5] Also in the portfolio is an excellent water-colour of St Mary's Church by Watts with a note in Macquarie's hand that he laid the foundation stone on 23 December 1818.[5] Like the 1803 church, though, the rest of the labour on the towers, which were completed in 1819, was most likely the result of convict labour.[18]

When listing achievements in the colony, Macquarie noted that at Parramatta he had "The Old Church repaired, new roofed, lengthened and greatly improved, inside and out, new Chancel and Spire being added thereto, the Outer Walls stuccoed in imitation of Stone, and the Church Yard enclosed with a neat Paling."[30]

In 1821 a clock built by Thwaites and Reed of London was installed in the north tower, with a single clock face pointing north. The clock has to be wound manually, requiring an ascent of two flights of stairs. This clock is one of the oldest still functioning timepieces in Australia.[2]

In 1902, Reverend James Samuel Hassall, published his book In Old Australia, Records and Reminiscences from 1794, in which he gives the following description of this church:

“The church, in which my grandfather officiation, old St John’s, was a large brick building, stuccoed, with two towers and spires. The church itself was removed afterwards, and was rebuilt of stone, all but the towers, which are still standing. …Within were high pews and galleries. The soldiers sat in one gallery, and afterwards, the King’s School Boys in another. A high pulpit stood in the middle of the church. I remember my grandfather preaching from it about the patriarchs and saying that Abraham was a squatter on Government ground. The reading-desk was below the pulpit, and the clerk’s desk somewhat lower still. The clerk’s desk was occupied for many years by Mr. J. Staff, who repeated the responses and amens in a loud voice and gave out the hymns.”[9]

In 1838 Reverend Marsden died and was replaced by Reverend H. H. Bobart, his son-in-law.

1850s reconstruction

St John's was damaged by a fierce storm on 21 December 1841 when the chamber between the two towers was heavily damaged by lightning. Its shingles and rafters were ripped apart and the roofing lead was swept away. "The whole west end appears shaken" wrote an observer.[31] At a meeting in the vestry on 14 April 1846, Reverend H. H. Bobart noted the poor condition of the church roof. A campaign commenced to raise funds to replace it.[2][32]

In April 1850, it was reported St John's had two roofs, and the outer one was leaking water into the cavity where it ran into the walls. The steeples were losing their shingles. The exterior timber needed paint and the stucco on the walls was flaking away.[33] By June 1852, the Church was reported to be a "perfect ruin". The roof was removed and the walls needed replacing. When removing the laths, the ceiling joists fell in several places. A decision had already been made to replace the church.[34] Local architect and builder James Houison was contracted to complete the new nave and chancel for £1,350 ($2,700).[2][35]

Late in July 1852, when workmen were removing the foundations of the church during demolition, they found a copper sheet in Latin.[36] It translates as, "The foundation stone of this church was laid Anno Domini 1799, during the Governorship of John Hunter. George III, King of England, has reigned 38 years".[2][37]

Reverend H. H. Bobart and churchwardens Francis Watkins, E. Rowling and J. McManus were responsible for the plan of the new church.[35] It would be "Saxon" in design (i.e. Norman) with semi-circular windows and doors, with interior arches and columns of similar character. Proposals to include Gothic windows were rejected by the churchwardens, as it would confuse the design. The Herald suggested that a "massive Saxon door" be erected at the western end.[38] In 1915, the Minister W J Gunther reported that the "Norman doorway" between the two towers was the design of Reverend H. H. Bobart.[2][39]

Bishop William Broughton, when laying the foundation stone on 11 August 1852 (before his return to England) also changed the dedication of the church when he noted that he laid "the foundation stone of a Church to be rebuilt in this place named the Church of St John the Evangelist".[2][40][41]

The nave and aisles were re-opened for Divine Service on 1 July 1855.[42] Gunther stated this was when church was dedicated.[43] The Church was properly consecrated by a service by Bishop Barker on 19 March 1858.[44] The towers were re-coated and lightning conductors were added and galvanised tiles replaced the shingles.[45] By April 1858, the cost of rebuilding the church, repairing the towers and erecting a lodge amounted to (Pounds)5,864 ($11,728) with (Pounds)900 ($1,800) still owed to Houison.[46] Re-building in stone removed the older brick church except the towers erected by Watts for Macquarie.[9] In the renovations of the 1850s, the tower windows were altered to round headed ones to accord with the Norman style of architecture.[2][47]

The land had not yet been granted to the Church. On 11 January 1856, surveyor M. Burrowes transmitted his plan of the Church land for grant purposes. It showed the church outline on the site plus some small buildings in the south-west corner of the site (C.584.730 Crown Plan). On 22 December 1857, the United Church of England and Ireland was granted the church site as 1 acre 2 roods 18 perches (Grants, volume 330, No 57/3, Lands). The 1856 Plan of Site aligns with Lot 2 DP 1110057 (at October 2009).[2]

The church lands were enlarged around 1911 with the addition of a land parcel fronting Hunter Street on the north-western boundary of the site. The 1910 Memorial Church hall and later church hall additions were built on this additional land parcel (which aligns with Lot 1 DP1110057 at October 2009).[2]

The foundation stone of two transepts designed by Blacket and Sons was laid on 24 April 1883.[42] Cyril Blacket appears to have completed the design after he borrowed Houison's plans and matched his detail so that the new work blended in successfully. Robert Kirkham a Sydney stonemason and contractor undertook the construction work.[48] This was completed in November 1883 and a service held. Additionally, the lower part of the towers was re-cemented to 8 feet above the ground.[49] In a fierce storm on 10 November 1885 lightning struck the lightning rod on the tower but jumped across into the tower wall cracking it and blasting a hole a foot in diameter, shearing off plaster and smashing the vestry ceiling.[50][2]

With the addition of the transepts and vestries in 1885 the church building took on its present form.[2]

On 15 September 1917 the laying of the foundation stone of the Royal Memorial Gateway was carried out by the Lt-Governor. This memorial to the soldiers of St. John's was opened and dedicated by the Governor General on 23 March 1918 before a crowd of "thousands of spectators". The Governor-General had secured King George V's permission to place the royal coat of arms over the gates.[51][2]

A peal of 13 bells (the memorial carillon) was installed in the southern tower in 1923 and these were dedicated before a crowd of "about 4,000 persons" by the Archbishop of Sydney on 26 May 1923.[2][52]

During the 1960s, in the process of re-coating the towers, workmen found that in the course of original construction, rough bush poles inserted into the brickwork had provided scaffolding. They were cut off as the rendering work proceeded from the top of the tower to the bottom.[2][53]

St. John's was granted the status of a Provisional Cathedral with the appointment of the first Bishop in Parramatta in 1969, who became the Bishop of Western Sydney in 1998.[2]

The Cathedral grounds were first opened to the public in 1953. Since the 1986 closure of Church Street to motor vehicles, the parish council administration, St John's clergy and Parramatta City Council have worked co-operatively to open up the church's grounds to community access and use.[2]

Although the church building is a traditional cruciform Anglican church, the uses to which it is put continue to evolve. Services range from traditional prayer book with organ music, hymns and robed clergy to modern more informal styles using contemporary music and instruments and incorporating computerized sound and projection systems. Also St. John's now reflects the rich cultural diversity of the City of Parramatta with services being conducted in four languages: English, Mandarin, Cantonese and Farsi.[2]

Description

Setting and grounds

St. Johns Anglican Cathedral sits (today) in the heart of Parramatta's Centennial Square, its former town square and Governor Macquarie's market place.[2]

The extensive church grounds (which are open to the public) are largely landscaped with flower beds, lawns, hedges and several established trees. A small late Victorian cottage, probably originally the verger's cottage, is located on the south-west corner of the site. The Royal Memorial Gates stand at the Church Street entrance to the grounds. These were erected in 1918 by the congregation as a memorial to men and women who volunteered for service in World War I. The pillars of the gates serve as a roll of honour and include the memorial's dedication on 23 March 1918. The stonework over the gateway displays the Royal Arms, permission for this being granted by King George V in November 1917.[2]

The surroundings of the cathedral are grassed to south and east, and paved to west and north, with some English oak (Quercus robur) trees and a brush box (Lophostemon confertus) amongst paving. A number of hybrid plane trees (Platanus x hybrida) also mark the north-running alignment of Church Street south to the cathedral. Several plaques around the oldest oak, commemorate the commencement and completion of the Church Street mall, which was the last major transformation of this space, closing off this section of Church Street between Darcy and Macquarie Streets, making it a pedestrian only space.[2]

Major trees south of the cathedral include jacarandas (Jacaranda mimosifolia) and brush boxes along the southern boundary of the space and further north. A mature Norfolk Island hibiscus / white oak / cow itch tree (Lagunaria patersonia) is also to the cathedral's south-east, in lawn. A line of hybrid plane trees traces the former kerb line of Church Street through what is now paved pedestrian mall.[2]

Church Hall

The 1910 Memorial Church Hall and its associated later buildings are located in the north-west corner of the Centennial Square/the Cathedral grounds which provide hall and parish office premises and car parking.[2]

Cathedral

.jpg.webp)

The cathedral itself was built in three main stages, St John's Anglican Cathedral combines Victorian Romanesque style with an earlier pair of Old Colonial Gothick towers.[2]

The oldest part of the current building, the two western towers, were built between 1817 and 1819 on apparently new foundations to replace the collapsed vestry. The towers are modelled on the towers of the ruined 12th century Saxon Church of St Mary's at Reculver, Kent, England. The towers are four-storey structures of handmade sandstock bricks overlaid with cement render to give the appearance of stone. Each tower is divided into four storeys by string courses and topped by a tall copper clad spire. The corners have rendered quoins. Each level of the towers has small arched openings on the external faces. The openings on the top levels have louvred vents. On the first floor the openings have a window sash divided into a pair of pointed arches. At the ground floor of the towers, there is a pair of arched openings. The northern tower has a black clock face with gold markings on the upper floor of the north face. The spires are pyramidal with a broached base and are each topped by a cross. On each face of the spires is a vent.[2]

The rest of the church building is constructed from local sandstone in the Victorian Romanesque style. This is demonstrated in the round-headed windows, round arches and columns in the nave and plain pillars. The mouldings and motifs of the door and panelling all display particular features of the style. Features of the Romanesque style are repeated internally and externally on the stonework and preserved in the later woodwork and fittings.[2]

The nave and chancel of the church were built between 1852 and 1855 under the direction of James Houison, a noted architect and builder of Parramatta. The style of the church is Victorian Romanesque, due to the decision of Reverend H. H. Bobart and his church wardens that the new church should be Saxon (ie Norman) in design. A gabled roof with parapets at the east and west end is centred between the towers. Lower roofs over the side aisles are terminated at the west end by the towers.[2]

Transepts added in 1883 to the design of Cyril Blacket continued the Saxon theme. An entry porch is located on the northern side. Vestry rooms are located on the eastern side of the transepts. The walls are of sandstone, smooth faced and margined to the quoins and sparrowpecked to the main walls. The roof is clad with slate shingles. Guttering is copper with a quad profile. Rainwater heads have the Fleur de Lis motif representing the trinity.[2]

The church has its main entry at the west end, between the towers, facing the eastern end of Hunter Street. The entry is a large arch with moulded recesses. Above the arch is a pair of arched windows then a circular window near the top of the gable.[2]

The faces on either side of the eastern and western windows are reminiscent of early medieval ecclesiastical architecture as are the crude lion heads above the eastern windows.[2]

The mouldings on the western door are repeated in part on all of the internal woodwork, reredos, communion table, pulpit and round the external stonework of the windows. The western door has five rows of mouldings

- a triple row of chevrons (zigzags), the most common of the decorations

- beakheads. A grotesque and crude ornament suggesting either a head with a beak or a tongue hanging out like a cat's. The western door has three different beakhead designs, carved in pairs and repeated in sequence. The heads characterise owls, pigs and cats

- ball flowers. A spherical flower with three lobes opening to show an enclosed sphere. This was commonly used in the 14th century

- cog-like design, representing the teeth on a cog

- chevrons, repeated.[2]

The nave of the church is divided by buttresses into four bays between the transepts and the tower. Each bay has an arched opening to the nave and to the aisle with a series of recessed mouldings. The chevron motif, typical of Saxon design, features in the recesses. A label mould finishes the top of the openings. The east wall of the church has three tall arched openings. All the windows to the church have stained glass. At the eaves and near the top of the parapet walls, the stonework is finished with a dentilated motif. Stone crosses top the east and west facing parapet gables. Metal finials are at the top of the north and south parapet gables.[2]

Inside the Cathedral, the reredos repeats the chevron and ball flower designs and also includes billets, which are small cylindrical blocks set in a hollow. These are also carved into the stone below the eastern windows. Another common motif that decorates the pulpit is the dog-tooth which consists of a row of pyramidical projections, each carved with four leaves.[2]

The Cathedral's present day interior contains church furniture, furnishings and stained glass windows as well as a number of memorials and items of historical significance. These include:[2]

- the 1599 Geneva (Breeches) Elizabethan Bible from Bath, England, located in the south transept;

- the London-made clock installed in 1821 in the northern tower;

- the 1846 tapestry, with portraits, that illustrates the unusual three-decker pulpit (for the rector, curate and clerk) that was used at St John's until 1855;

- the JW Walker pipe organ brought from England in 1862, installed in the western gallery in 1863 and moved to the north transept in 1900;

- 13 memorial bells installed in the southern tower in 1923 with associated tablet;

- the font carved from totara wood and inlaid with paua shell, gifted by representative Maoris from New Zealand and installed in 1969 to commemorate the ministry of the Rev Samuel Marsden (the first rector of St John's), to the Maoris' from 1814;

- a piece of stone from the Reculver Towers of the 12th century St Mary's Church, Kent, England with associated plaque mounted in the west wall;

- tapestries depicting Parramatta landmarks and flora located in the Sanctuary, the Chancel and some front pews.

There are significant memorials located within the Cathedral's interior, including the stained glass windows memorial tablets. Pre-1850 tablets commemorate the Rev Samuel Marsden (died 1838); Elizabeth Jane, wife of Governor Bourke (died 1832); John Blaxland (died 1845), and the first confirmation in Australia (1836).[2]

Modifications and dates

Timber shingled cladding to spires replaced with copper.[2]

- 1852–55: Tower windows changed to arches

- 1863: JW Walker organ installed in the western gallery

- 1883: Transepts added to accommodate 80–90 people

- 1900: JW Walker organ moved into the north transept with the choir

- 1918: Royal Memorial Gates installed (facing Church Street)

- 1923: Memorial carillon of 13 bells installed in south tower

- 1967: Major sub-floor ventilation works, including removal of centre aisle tiles and laying of new floorboards

- 1966: JW Walker organ restored

- 1969: Maori font installed

- 1972: Towers re-rendered

- 1988: South transept displays the 1599 Geneva Bible

- 1990s: Garage built for cottage in south-west corner of the site.

Heritage listing

St John's Cathedral is of state significance as the oldest church site and continuous place of Christian worship in Australia, dating from 1803; as one of the two oldest parishes proclaimed in Australia in 1802; for potential archaeology of the 1803 parish church of St John's that was the first parish church built in Australia, and for the historical significance and rarity of the two towers built in 1817–19 by Governor Macquarie and his wife Elizabeth that are the only surviving fabric of the first church of St John's, the oldest remaining part of any Anglican church in Australia and a rare surviving legacy of Governor Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie to the built environment of NSW.[2]

Governor King's 1802 proclamation of the first two parishes of the colony of NSW—St John's Parramatta and St Phillip's Sydney—demonstrated the colony's early spiritual development and the formal recognition of the Church of England as the recognised denomination of the colony. The present St Johns' parish church (now Cathedral) is built on the site of the first (1803) parish church, whereas the present St Phillip's Church, York Street, Sydney has moved from the site of the first (1809) St Phillip's parish church that was built at nearby Lang Park.[2]

St John's Anglican Cathedral was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 5 March 2010 having satisfied the following criteria.[2]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

St John's Cathedral, Parramatta has historical significance at State level as the site of one of the two earliest Anglican parishes established in Australia (1802); the site of the first parish church built in Australia (1803) and the only such site to have remained in continuous use as a church from 1803 to the present time; and for its towers built in 1817–19 which are the only surviving fabric of the first St John's church and a rare surviving legacy of Governor Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie to the built environment of NSW.[2]

St John's has long been regarded as one of the mother churches of Australia. In 1802, Governor King proclaimed the first two churches in Australia – St Philip's, Sydney and St John's, Parramatta. This act confirmed the Church of England as the official denomination of the colony, extending the power of the Church of England from Britain to Australia. As the church of the second mainland settlement of the colony, the creation of the parish of St John's embedded religion into the social values of colony.[2]

Remains of the original 1803 brick parish church may still survive as archaeological evidence. The surviving fabric of this first parish church built in the colony dates from 1817–1819, being the two towers commissioned by Governor Lachlan Macquarie which follow the design model suggested by Elizabeth Macquarie and implemented by Lt John Watts. These towers are the oldest remaining part of any Anglican church in Australia.[2]

The erection of the extant towers was a significant element of Governor Macquarie's programme of fostering religion and education as well as his desire to make Parramatta (the second mainland settlement of the colony and the site of his second Government House) into a tidy, well-ordered settlement.[2]

Surviving views and vistas of St Johns Cathedral have state historical significance. These include: east along Hunter Street to the Cathedral towers; east from Hunter Street across the northern Cathedral grounds towards the Town Hall and the site of the Governor's annual "feast" with Aboriginal clans (instituted by Governor Macquarie) that took place at the rear (eastern end) of the Cathedral, and views from Church Street towards St John's Cathedral.[2]

The Cathedral contains furniture, furnishings, fixtures, fittings, memorial and items of moveable heritage of historical significance. These, together with the Royal Memorial Gates in the grounds, are detailed in the Description field.[2]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

St John's Cathedral meets this criterion of State significance because it has strong associations with three early colonial governor's, with Elizabeth Macquarie (wife of one of these governors) and with Lt John Watts as an important early designer of colonial buildings, especially in Parramatta. It also has associations with colonial architects John Houison and Cyril Blacket and with the regiment of Royal NSW Lancers stationed in Parramatta. Governor Lachlan Macquarie ordered the construction of the towers and his wife Elizabeth Macquarie provided the model for the tower design. Lt John Watts (who was also responsible for the design of Macquarie's extensions to Old Government House, Parramatta) implemented Elizabeth Macquarie's design for the towers.[2]

Reverend Samuel Marsden, resident of Parramatta from 1794 to his death in 1838 and the first rector of St John's, was long associated with this church and is regarded by Anglicans as one of their founding ministers.[2]

The church is associated with Governor Hunter, who left a major legacy in the infant colony by his promotion of religion and churches. He laid the foundation stone of the original brick church in 1797 or 1798 and in 1802 proclaimed the Parish of St John's Parramatta. St John's has been the parish church since 1803. The church of St John's was named in Governor Hunter's honour by Governor King when he set up the parishes in Parramatta and Sydney in 1802.[2]

The site is associated with Governor King who proclaimed the Parish of St John's Parramatta in 1802 and named the parish church of St John's for Governor Hunter in 1803.[2]

The Cathedral is significant as the work of three notable architects who worked in New South Wales in the nineteenth century: Lieutenant John Watts, James Houison and Cyril Blacket.[2]

St John's is associated with the regiment of Royal NSW Lancers, stationed in Parramatta from 1897.[2]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

St John's Cathedral meets this criterion of State significance because the towers of St John's Anglican Cathedral, Parramatta show the influence of Governor Lachlan Macquarie and his wife Elizabeth who suggested the use of the Reculver church for the design of the original St John's Chapel, and also by demonstrating the key role of Lt John Watts in advancing this design with speed and efficiency as well as Macquarie's wider programme of building in Parramatta.[2]

The design of St John's demonstrates the importance Macquarie placed on constructing civic buildings of style that would both improve and civilise the convict colony of NSW.[2]

The towers of St John's Cathedral are an important surviving element of Macquarie's ambitious public works program.[2]

The towers were a focal point in the nineteenth century townscape of Parramatta. Although hidden by higher more recent development from more distant views, they continue to be an important part of the streetscape of Parramatta. The twin spires of St John's have long been an important element of the civic identity and landscape of Parramatta. They dominate the town in almost every nineteenth century view of Parramatta.[2]

The Cathedral is significant as the work of three notable architects who worked in New South Wales in the nineteenth century: Lieutenant John Watts, James Houison and Cyril Blacket.[2]

The overall design is a fine example of the Victorian Romanesque style utilising the towers of the previous chapel on the site to frame the western front and to visually anchor the building.[2]

Three extant churches survive from the Macquarie era; St James Church, King Street, Sydney; St Matthew's, Windsor; and St Luke's, Liverpool. All are churches designed by Macquarie's Civil Architect, ex-convict Francis Greenway. Their extant fabric and visual impact demonstrate Macquarie's grand scheme to enhance the built form and aesthetics of the colony as well as his programme of re-vitalising convict society through religion as well as education.[2]

The towers of St John's Church, Parramatta, though not designed by Greenway, are an important demonstration of the same aims in the second town of the colony and illustrate Macquarie's desire to undertake the same re-vitalisation by boosting an existing church, as part of his wider scheme of improving Parramatta.[2]

The place has strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

It meets this criterion of State significance as St John's has been the centre of an active Anglican community since its inception. This activity has continued to the present day.[2]

The parish of St John's Parramatta originally catered for the whole of the western Cumberland Plain. Parishioners came from surrounding districts to worship at St John's. As settlement progressed, St John's established satellite churches which evolved into separate parishes.[2]

The Anglican Church has acknowledged its ongoing commitment to the continued preservation of the Cathedral as a significant item of Anglican heritage in Australia for the purpose of continued Christian worship. The commitment of its parishioners is ongoing.[2]

St John's Cathedral has local heritage significance as a landmark site of community esteem in the Sydney's second city and demographic centre. The Cathedral is a prominent landmark located in park-like grounds that are daily traversed by Parramatta's large population of commuters en route to the bus and rail interchange.[2]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

It appears to meet this criterion of State significance due to the potential archaeological remains on this site of the 1803 brick parish church of St John's, the first parish church built in Australia.[2]

Any surviving archaeology from the 1803 church would provide rare and significant evidence of the earliest establishment of Christian worship in the penal colony of NSW.[2]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

It meets this criterion of State significance as the site of the original 1803 brick parish church which was the first parish church built in the colony. Archaeology of this building may still survive in the vicinity of the current Cathedral building as a rare resource with potential to reveal data about early church building in convict Australia.[2]

The two towers constructed in 1817–1819 are the only surviving fabric of this first church building. As such they have rarity at state level as the oldest remaining part of any Anglican church in Australia and as rare extant examples of the legacy of Governor Lachlan and Elizabeth Macquarie to the built environment of NSW. The towers are also rare in Australian ecclesiastical architecture as the only church towers constructed in the colonial period and one of the small number of church or cathedral towers built to date in Australia.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ The Heritage of Australia, Macmillan Company, 1981, p.2/50

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 "St. John's Anglican Cathedral". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01805. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - ↑ Parramatta Heritage Study, Parramatta Council, 1992

- ↑ Rapp, C.; Pearce, J.; Roe, J. (1988). St. John's Parramatta. p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Walker, Frank (1918). "St John's Cathedral". Journal and Proceedings. Parramatta and District Historical Society. 1: n.r.

- ↑ Hassall 1902, p. 1.

- ↑ Marsden, Samuel (1932). Elder, John (ed.). The letters and journals of Samuel Marsden, 1765-1838 (1st ed.). Coulls Somerville Wilkie and A.H. Reed for the Otago University Council. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- 1 2 Marsden, Samuel (1978). Bladen, F. M. (ed.). A Letter from Sydney, Port Jackson, 14 September 1798. Vol. 3. Mona Vale, NSW: Lansdown Slattery. p. 487. Archived from the original on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 Hassall 1902, p. 11.

- 1 2 Hassall 1902, p. 146.

- ↑ Hunter, John (1914). Watson, Frederick (ed.). Governor Hunter to The Duke of Portland, 10 January 1798. Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament. pp. 120–21. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Hunter, John (1914). Watson, Frederick (ed.). Governor Hunter to The Duke of Portland (Despatch No. 38, per store-ship Marquis Cornwallis, via Bengal), 1 November 1798. Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament. p. 237. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 Collins, David (1802). An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales. Vol. II. London: T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies, in The Strand. p. 134. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ↑ Hunter, John (1914). Watson, Frederick (ed.). Governor Hunter to Under Secretary King, (Per H.M.S. Buffalo), 25 September 1800. Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament. p. 237. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 King, Philip Gidley (21 August 1801). "Letter Received by Sir Joseph Banks from Philip Gidley King, 21 August 1801". Banks Papers: Series 39: Correspondence, Being Mainly Letters Received by Banks from Philip Gidley King, with Related Papers, 1788, 1791–1807. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ↑ King, Philip Gidley (1915). Watson, Frederick (ed.). Governor King to Lord Hobart, 23 July 1802. Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament. pp. 630–31. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ "Sydney". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803–1842). 17 April 1803. p. 3. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018.

- 1 2 "St. John's Anglican Cemetery". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H000049.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - ↑ King, Philip Gidley (1915). Watson, Frederick (ed.). Governor King to Lord Hobart, 1 March 1804. Vol. IV: 1803–June 1804. Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament. p. 470–71. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Bligh, William. Parramatta Church, built of Brick, and in a very bad State; unfinished in the Inside. Stands in a Swamp. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. Archived from the original (sketch c. 1806) on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Higghinbothan, Edward (1983). "The excavation of a brick barrel drain at Parramatta, NSW". Australian Journal of Historical Archaeology. 1: 35–39.

- ↑ Bligh, William (1916). Watson, Frederick (ed.). Governor Bligh to The Right Hon. William Windham, 25 January 1807. ENCLOSURE: Situation and Description of Repair of Government Buildings, New South Wales, 13th August, 1806," and William Bligh, "Governor Bligh to The Right Hon. William Windham, 7 February 1807," and William Bligh, "Governor Bligh to The Right Hon. William Windham, 31 October 1807. Enclosure No. 3: State of Government Buildings, in New South Wales, the 13th August, 1807. Vol. VI, August 1806–December 1808. Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament. pp. 98, 125, 170. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Houison, Andrew (1903). Odd Bits in the History of Parramatta. Parramatta, NSW: Andrew Houison. p. 124.

- ↑ SRNSW 4/3490C, p. 142 "St. John's Anglican Cemetery". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H000049.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - ↑ SRNSW 4/1725, p. 322 cited in "St. John's Anglican Cemetery". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H000049.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - ↑ Wentworth Papers, ML D1, p. 29 cited in "St. John's Anglican Cemetery". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H000049.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - ↑ "The Committee of the Female Orphan Institution at Parramatta". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW: 1803–1842. 5 February 1814. p. 2. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018.

- ↑ Kerr, Joan; Broadbent, James (1980). Gothick Taste in the Colony of New South Wales. Sydney: David Ell Press, in association with the Elizabeth Bay House Trust. p. 39. ISBN 090819711X.

- ↑ Macfarlane, Margaret; Macfarlane, Alastair (1992). John Watts: Australia's Forgotten Architect, 1814–1819, and South Australia's Postmaster General, 1841–1861. Bonnells Bay, NSW: Sunbird Publications. p. 38.

- ↑ Macquarie, Lachlan (1819). Watson, Frederick (ed.). "Major-General Macquarie to Earl Bathurst: 27 July 1822". Historical Records of Australia; SERIES I: Governors' Despatches to and from England (January 1819–December 1822 ed.). Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament. X: 689. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ "ORIGINAL CORRESPONDENCE". The Sydney Herald. Vol. XII, no. 1435. New South Wales, Australia. 24 December 1841. p. 2 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Jervis 1963, p. 9.

- ↑ "PARRAMATTA". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. XXVII, no. 4030. New South Wales, Australia. 17 April 1850. p. 2 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "PARRAMATTA". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. XXXII, no. 4705. New South Wales, Australia. 12 June 1852. p. 2 (Supplement to the Sydney Morning Herald) – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 Jervis 1963, p. 10.

- ↑ "PARRAMATTA". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. XXXIII, no. 4742. New South Wales, Australia. 26 July 1852. p. 2 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Jervis 1963, p. 5-6.

- ↑ "PARRAMATTA". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. XXXIII, no. 4753. New South Wales, Australia. 7 August 1852. p. 2 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "St. John's Towers". The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate. Vol. XXVIII, no. 2216. New South Wales, Australia. 28 April 1915. p. 1 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "PARAMATTA". The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales, Australia. 14 August 1852. p. 3 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Bennett & Byrne 2005.

- 1 2 "St. John's, Parramatta". The Cumberland Mercury. Vol. XVIII, no. 989. New South Wales, Australia. 28 April 1883. p. 4 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Gunther, W. J. (William James) (1910). A short history of the church and parish of St. John, Parramatta. W.J. Gunther. p. 9.

- ↑ Jervis 1963, p. 11.

- ↑ Jervis 1963, p. 12.

- ↑ "NEW NOTICES OF MOTION". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. XXXIX, no. 6196. New South Wales, Australia. 15 April 1858. p. 5 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Macfarlane & Macfarlane 1992, p. 39.

- ↑ [42] See list of names included in the foundation stone of the new transepts. The list concludes with the names Cyril Blackett, architect and R. Kirkham, contractor. Cumberland Mercury, 28 April 1883, p.4. [new footnote needed] See Blacket architectural drawings, NSW Public Library: Series 02, part 5; churches—Suburban (Sydney) p. 5, vol. 1. Parramatta St. John's church and school (1854-1889-1907) ff 22 PXD 200 vol 1. R. In accordance with the custom of the Blackets, the contractor was required to sign drawings of the transepts. R. Kirkham duly signed several drawings of the plans for the transepts. The only Kirkham building in Sydney at the time was Robert Kirkham who had built a number of Blacket designed buildings. Among them were St. Stephen's, Newtown, the central tower of St. Andrews's Cathedral, All Saints' Church, Woollara, the Sydney Industrial Blind Institute, and a shop and warehouse for John Macintosh and Sons, Pitt Street, Sydney. He was later to add enlarged chancel at St. John's, Darlinghurst.

- ↑ Jervis 1963, p. 13.

- ↑ "Local and General". The Cumberland Mercury. Vol. XX, no. 1252. New South Wales, Australia. 11 November 1885. p. 2 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ St John's, 1918; pers. comm. Pearce, 2009

- ↑ Johnstone, S. M. (Samuel Martin), 1879-1949; St. John's Church (Parramatta, N.S.W.) (1923). The Bells of St. John's, Parramatta. The Church. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Macfarlane & Macfarlane 1992, p. 42.

Bibliography

- St John's Cathedral Parramatta Welcomes You. 2005.

- Historical Records of Australia.

- Cumberland Mercury. 1878.

- Banks Papers (ML A85).

- Plans of buildings erected mainly at Parramatta by Lachlan Macquarie (ML D337).

- Arrowsmith, Herbert Maxwell. The Cradle Church of Australia.

- Bennett, K; Byrne, R (2005). St John's Anglican Cathedral, Parramatta, Australia – Facts File.

- Collins, David (1804). An Account of the English colony in New South Wales.

- Colonial Office. Correspondence CO 323, 140.

- Elder, JR (1932). The Letters and Journals of Samuel Marsden 1765–1838.

- Marsden, Samuel (1932). Elder, John (ed.). The letters and journals of Samuel Marsden, 1765-1838 (1st ed.). Coulls Somerville Wilkie and A.H. Reed for the Otago University Council.

- Hassall, James Samuel (1902). In old Australia : records and reminiscences from 1794. Hews, Library of Australian History. ISBN 9780908120062.

- Houison, Andrew (1903). Odd bits in the history of Parramatta.

- Jervis, J (1963). A Short History of St John's Church, Parramatta. Ambassador Press.

- Kass, Terry (2009). SHR Nomination.

- Kass, T; Liston, C; McClymont, J (1996). Parramatta: a past revealed.

- Macfarlane, Margaret; Macfarlane, Alastair (1992). John Watts : Australia's forgotten architect 1814-1819 and South Australia's postmaster general 1841-1861. SunBird Publications. ISBN 978-0-646-11695-2.

- Parramatta Sun Magazine (2013). 'Iconic St.John's Anglican Cathedral', in 'The Parramatta Sun Magazine' 4/2013.

- Jenny and Mark Pearce, Hon Archivists, St John's Cathedral, Parramatta (2009). Personal Communication with Heritage Branch, Department of Planning.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rapp, Chris; Pearce, Jenny; Roe, John (1988). St John's Parramatta. ISBN 9780909448967.

- Stedinger Associates (2009). Bicentennial square. Proposed landscape works: an archaeological assessment and excavation permit exception application.

- Walker, M. & Kass, T. (1983). Parramatta Heritage Study.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article contains material from St. John's Anglican Cathedral, entry number 01805 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.

This Wikipedia article contains material from St. John's Anglican Cathedral, entry number 01805 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.