| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

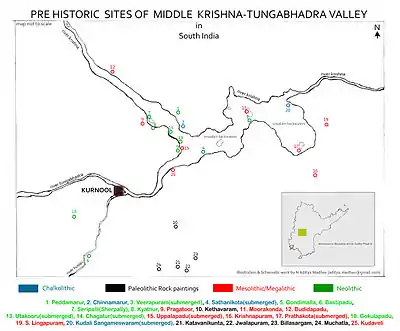

The South Asian Stone Age covers the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic periods in the Indian subcontinent. Evidence for the most ancient Homo sapiens in South Asia has been found in the cave sites of Cudappah of India, Batadombalena and Belilena in Sri Lanka.[1] In Mehrgarh, in what is today western Pakistan, the Neolithic began c. 7000 BCE and lasted until 3300 BCE and the first beginnings of the Bronze Age. In South India, the Mesolithic lasted until 3000 BCE, and the Neolithic until 1400 BCE, followed by a Megalithic transitional period mostly skipping the Bronze Age. The Iron Age in India began roughly simultaneously in North and South India, around c. 1200 to 1000 BCE (Painted Grey Ware culture, Hallur, Paiyampalli).

Homo erectus

Homo erectus lived on the Pothohar Plateau, in upper Punjab, Pakistan along the Soan River (nearby modern-day Rawalpindi) during the Pleistocene Epoch. Soanian sites are found in the Sivalik region across what are now North India, Pakistan and Nepal.[2] Biface handaxes and cleaver traditions may have originated in the middle Pleistocene.[3] The beginning of the use of Acheulian and chopping tools of the lower Paleolithic may also be dated to approximately the middle Pleistocene.[4]

Neolithic Stone Age (7000 BCE - 5500 BCE) finds were excavated from Pinjore in Haryana on the banks of the stream (paleochannel of Saraswati river) flowing through HMT complex,[5][6] by Guy Ellcock Pilgrim who was a British geologist and palaeontologist, who discovered 1.5 million years (15 lakhs) old prehistoric human teeth and part of a jaw denoting that the ancient people, who were intelligent hominins dating as far back as 1,500,000 ybp Acheulean period,[7] lived in Pinjore region near Chandigarh.[8] Quartzite tools of lower Paleolithic period were excavated in this region extending from Pinjore in Haryana to Nalagarh (Solan district) in Himachal Pradesh.[9]

The coming of Homo sapiens

Analysis of mitochondrial DNA dates the immigration of Homo sapiens into the subcontinent to 75,000 to 50,000 years ago.[10][11] Cave sites in Sri Lanka have yielded the earliest non-mitochondrial record of Homo sapiens in South Asia. They were dated to 34,000 years ago. (Kennedy 2000: 180). For finds from the Belan in southern Uttar Pradesh, India radiocarbon data have indicated an age of 18,000-17,000 years.

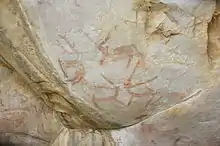

At the rock shelters of Bhimbetka there are cave paintings dating to c. 30,000 BCE,[12][13] and there are small cup like depressions at the end of the Auditorium Rock Shelter, which is dated to nearly 100,000 years;[14] the Sivaliks and the Potwar (Pakistan) region also exhibit many vertebrate fossil remains and paleolithic tools. Chert, jasper and quartzite were often used by humans during this period.[15]

Neolithic

The aceramic Neolithic (Mehrgarh I, Baluchistan, Pakistan, also dubbed "Early Food Producing Era") lasts c. 7000 - 5500 BCE. The ceramic Neolithic lasts up to 3300 BCE, blending into the Early Harappan (Chalcolithic to Early Bronze Age) period. One of the earliest Neolithic sites is Lahuradewa in the Middle Ganges region and Jhusi near the confluence of Ganges and Yamuna rivers, both dating to around the 7th millennium BCE.[16][17] Recently another site along the ancient Saraswati riverine system in the present day state of Haryana in India called Bhirrana has been discovered yielding a dating of around 7600 BCE for its Neolithic levels.[18]

In South India the Neolithic began by 3000 BCE and lasted until around 1400 BCE. South Indian Neolithic is characterized by Ashmounds since 2500 BCE in the Andhra-Karnataka region that expanded later into Tamil Nadu. Comparative excavations carried out in Adichanallur in the Thirunelveli District and in Northern India have provided evidence of a southward migration of the Megalithic culture.[19] The earliest clear evidence of the presence of the megalithic urn burials are those dating from around 1000 BCE, which have been discovered at various places in Tamil Nadu, notably at Adichanallur, 24 kilometers from Tirunelveli, where archaeologists from the Archaeological Survey of India unearthed 12 urns containing human skulls, skeletons and bones, husks, grains of charred rice and Neolithic celts, confirming the presence of the Neolithic period 2800 years ago. Archaeologists have made plans to return to Adhichanallur as a source of new knowledge in the future.[20][21]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kennedy, K. A. R.; Deraniyagala, S. U.; Roertgen, W. J.; Chiment, J.; Disotell, T. (April 1987). "Upper Pleistocene Fossil Hominids From Sri Lanka". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 72 (4): 441–461. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330720405. PMID 3111269.

- ↑ Parth R. Chauhan. Distribution of Acheulian sites in the Siwalik region Archived 2012-01-04 at the Wayback Machine. An Overview of the Siwalik Acheulian & Reconsidering Its Chronological Relationship with the Soanian – A Theoretical Perspective.

- ↑ Kennedy 2000, p. 136.

- ↑ Kennedy 2000, p. 160.

- ↑ Manmohan Kumar : Archaeology of Ambala and Kurukshetra Districts, Haryana, 1978, Mss, pp.240-241.

- ↑ Haryana Samvad, Oct 2018, p38-40.

- ↑ Early Pleistocene Presence of Acheulian Hominins in South India

- ↑ Pilgrim, Guy, E. 'New Shivalik Primates and their Bearing on the Question, of the Evolution of Man and the Anthropoides, Records of the Geological Survey of India, 1915, Vol.XIV, pp. 2-61.

- ↑ Haryana Gazateer, Revennue Dept of Haryana, Capter-V.

- ↑ Alice Roberts (2010). The Incredible Human Journey. A&C Black. p. 90.

- ↑ James & Petraglia 2005, S6.

- ↑ Doniger, Wendy (2010) [First published 2009]. The Hindus: An Alternative History. Oxford University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-19-959334-7.

- ↑ Jarzombek, Mark M. (2014) [First published 2013]. Architecture of First Societies: A Global Perspective. John Wiley & Sons. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-118-42105-5.

- ↑ Archaeological Survey of India, Government of India. "World Heritage Sites - Rock Shelters of Bhimbetka". Archaeological Survey of India, Government of India. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "Chert: Sedimentary Rock - Pictures, Definition, Formation". geology.com. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ↑ Fuller, Dorian (2006). "Agricultural Origins and Frontiers in South Asia: A Working Synthesis" (PDF). Journal of World Prehistory. 20: 42. doi:10.1007/s10963-006-9006-8. S2CID 189952275.

- ↑ Tewari, Rakesh et al. 2006. "Second Preliminary Report of the excavations at Lahuradewa, District Sant Kabir Nagar, UP 2002-2003-2004 & 2005-06" in Pragdhara No. 16 "Electronic Version p.28" Archived 2007-11-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Haryana's Bhirrana oldest Harappan site, Rakhigarhi Asia's largest: ASI". Times of India. 15 April 2015.

- ↑ Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta (1976). A History of South India. Oxford University Press. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-0-19-560686-7.

- ↑ Subramanian, T. S. (2004-05-26). "Skeletons, script found at ancient burial site in Tamil Nadu". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 2004-07-01. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamil A. (1992). Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature. Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-90-04-09365-2.

The most interesting pre-historic remains in Tamil India were discovered at Adichanallur. There is a series of urn burials. seem to be related to the megalithic complex.

References

- Kennedy, Kenneth Adrian Raine (2000). God-Apes and Fossil Men: Palaeoanthropology of South Asia. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472110131.

- James, Hannah V. A.; Petraglia, Michael D. (December 2005). "Modern Human Origins and the Evolution of Behavior in the Later Pleistocene Record of South Asia" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 46 (Supplement): S3. doi:10.1086/444365. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002B-0DBC-F. S2CID 12529822. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2006.

- Misra, V. N. (November 2001). "Prehistoric human colonization of India". Journal of Biosciences. 26 (4): 491–531. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.628.6715. doi:10.1007/BF02704749. PMID 11779962. S2CID 26248907.

- Biagi P, Kazi M M e Negrino F. 1996. An Acheulian workshop at Ziarat Pir Shaban on the Rohri Hills (Sindh - Pakistan). South Asian Studies, 12: 49–62. Cambridge.

- Biagi P, Kazi M.M, Madella M e Ottomano C. 1998-2000 - Excavations at the Late Palaeolithic site of ZPS2 in the Rohri Hills, Sindh, Pakistan. Origini, XXII: 111–133. Roma.

- Biagi P. 2003-2004 - The Mesolithic Settlement of Sindh (Pakistan): A Preliminary Assessment. Praehistoria, 4-5: 195–220. Miskolc.

- Biagi P. 2011 - Late (Upper) Palaeolithic Sites at Jhimpir in Lower Sindh (Pakistan). In Taskiran H., Kartal M., Özcelik K., Kösem M.B. and Kartal G. (eds.) Iş?n Yalç?nkaya'ya Armagan. Ankara University, Ankara: 67–84.

- Biagi P. and Nisbet R. 2011 - The Palaeolithic sites at Ongar in Sindh, Pakistan: a precious archaeological resource in danger. Antiquity Project Gallery. Antiquity 85 (329): 1–6. August 2011. http://www.antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/biagi329/. Cambridge.

- P. Biagi and E. Starnini 2014 - The Levallois Mousterian assemblages of Sindh (Pakistan) and their relations with the Middle Palaeolithic in the Indian Subcontinent. Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia, 42 (1): 18-32 (Elsevier English edition). Doi: 10.1016/j.aeae.2014.10.002.

- P. Biagi 2015 - Modeling the Past: The Paleoethnological Evidence. In W. Henke, I Tattersall (eds) Handbook of Paleoanthropology. Springer Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg (2nd revised Edition): 817-843 Doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-27800-6_24-3.

- P. Biagi 2017 - Why so many different stones? The Late (Upper) Palaeolithic of Sindh reconsidered. Journal of Asian Civilizations, 40 (1): 1-40.

- P. Biagi and E. Starnini E. 2018 - Neanderthals and Modern Humans in the Indus Valley? The Middle and Late (Upper) Palaeolithic Settlement of Sindh, a Forgotten Region of the Indian Subcontinent. In: Nishiaki Y. and Akazawa T. (eds.) The Middle and Upper Paleolithic Archeology of the Levant and Beyond. Replacement of Neanderthals by Modern Humans Series. Springer, Singapore: 175–197. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-6826-3_12.