| Su-27 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Su-27SKM at MAKS-2005 airshow | |

| Role | Multirole fighter, air superiority fighter |

| National origin | Soviet Union / Russia |

| Manufacturer | Sukhoi |

| First flight | 20 May 1977 |

| Introduction | 22 June 1985 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Russian Aerospace Forces People's Liberation Army Air Force Uzbekistan Air and Air Defence Forces See Operators section for others |

| Produced | 1982–present |

| Number built | 680[1] |

| Variants | Sukhoi Su-30 Sukhoi Su-33 Sukhoi Su-34 Sukhoi Su-35 Sukhoi Su-37 Shenyang J-11 |

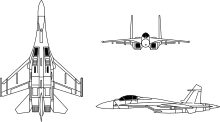

The Sukhoi Su-27 (Russian: Сухой Су-27; NATO reporting name: Flanker) is a Soviet-origin twin-engine supersonic supermaneuverable fighter aircraft designed by Sukhoi. It was intended as a direct competitor for the large US fourth-generation jet fighters such as the Grumman F-14 Tomcat and McDonnell Douglas F-15 Eagle, with 3,530-kilometre (1,910 nmi) range, heavy aircraft ordnance, sophisticated avionics and high maneuverability. The Su-27 was designed for air superiority missions, and subsequent variants are able to perform almost all aerial warfare operations. It was designed with the Mikoyan MiG-29 as its complement.

The Su-27 entered service with the Soviet Air Forces in 1985. The primary role was long range air defence against American SAC Rockwell B-1B Lancer and Boeing B-52G and H Stratofortress bombers, protecting the Soviet coast from aircraft carriers and flying long range fighter escort for Soviet heavy bombers such as the Tupolev Tu-95, Tupolev Tu-22M and Tupolev Tu-160.[2]

The Su-27 was developed into a family of aircraft; these include the Su-30, a two-seat, dual-role fighter for all-weather, air-to-air and air-to-surface deep interdiction missions, and the Su-33, a naval fleet defense interceptor for use from aircraft carriers. Further versions include the side-by-side two-seat Su-34 strike/fighter-bomber variant, and the Su-35 improved air superiority and multi-role fighter. A thrust-vectoring version was created, called the Su-37. The Shenyang J-11 is a Chinese license-built version of the Su-27.

Development

In 1969, the Soviet Union learned of the U.S. Air Force's "F-X" program, which resulted in the F-15 Eagle. The Soviet leadership soon realized that the new American fighter would represent a serious technological advantage over existing Soviet fighters. "What was needed was a better-balanced fighter with both good agility and sophisticated systems." In response, the Soviet General Staff issued a requirement for a Perspektivnyy Frontovoy Istrebitel (PFI, literally "Prospective Frontline Fighter", roughly "Advanced Frontline Fighter").[3] Specifications were extremely ambitious, calling for long-range, good short-field performance (including the ability to use austere runways), excellent agility, Mach 2+ speed, and heavy armament. The aerodynamic design for the new aircraft was largely carried out by TsAGI in collaboration with the Sukhoi design bureau.[3]

When the specification proved too challenging and costly for a single aircraft in the number needed, the PFI specification was split into two: the LPFI (Lyogkyi PFI, Lightweight PFI) and the TPFI (Tyazholyi PFI, Heavy PFI). The LPFI program resulted in the Mikoyan MiG-29, a relatively short-range tactical fighter, while the TPFI program was assigned to Sukhoi OKB, which eventually produced the Su-27 and its various derivatives.

The Sukhoi design, which was altered progressively to reflect Soviet awareness of the F-15's specifications, emerged as the T-10 (Sukhoi's 10th design), which first flew on 20 May 1977. The aircraft had a large wing, clipped, with two separate podded engines and a twin tail. The 'tunnel' between the two engines, as on the F-14 Tomcat, acts both as an additional lifting surface and hides armament from radar.

Air Force

The T-10 was spotted by Western observers and assigned the NATO reporting name 'Flanker-A'. The development of the T-10 was marked by considerable problems, leading to a fatal crash of the second prototype, the T-10-2 on 7 July 1978,[4] due to shortcomings in the fly-by-wire control system.[5] Extensive redesigns followed (T-10-3 through T-10-15) and a revised version of the T-10-7, now designated the T-10S, made its first flight on 20 April 1981. It also crashed due to control problems and was replaced by T-10-12 which became T-10S-2. This one also crashed on 23 December 1981 during a high-speed test, killing the pilot.[6] Eventually the T-10-15 demonstrator, T-10S-3, evolved into the definitive Su-27 configuration.[7]

The T-10S-3 was modified and officially designated the P-42, setting a number of world records for time-to-height,[8] beating those set in 1975 by a similarly modified F-15 called "The Streak Eagle".[9] The P-42 "Streak Flanker" was stripped of all armament, radar and operational equipment. The fin tips, tail-boom and the wingtip launch rails were also removed. The composite radome was replaced by a lighter metal version. The aircraft was stripped of paint, polished and all drag-producing gaps and joints were sealed. The engines were modified to deliver an increase in thrust of 1,000 kg (2,200 lb), resulting in a thrust-to-weight ratio of almost 2:1 (for comparison with standard example see Specifications).[10][11]

.jpg.webp)

The production Su-27 (sometimes Su-27S, NATO designation 'Flanker-B') began to enter VVS operational service in 1985, although manufacturing difficulties kept it from appearing in strength until 1990.[12] The Su-27 served with both the V-PVO and Frontal Aviation. Operational conversion of units to the type occurred using the Su-27UB (Russian for Uchebno Boevoy - "combat trainer", NATO designation 'Flanker-C') twin-seat trainer, with the pilots seated in tandem.

When the naval Flanker trainer was being conceived the Soviet Air Force was evaluating a replacement for the Su-24 "Fencer" strike aircraft, and it became evident to Soviet planners at the time that a replacement for the Su-24 would need to be capable of surviving engagements with the new American F-15 and F-16. The Sukhoi bureau concentrated on adaptations of the standard Su-27UB tandem-seat trainer. However, the Soviet Air Force favoured the crew station (side-by-side seating) approach used in the Su-24 as it worked better for the high workload and potentially long endurance strike roles. Therefore, the conceptual naval side-by-side seated trainer was used as the basis for development of the Su-27IB (Russian for Istrebityel Bombardirovshchik - "fighter bomber") as an Su-24 replacement in 1983. The first production airframe was flown in early 1994 and renamed the Su-34 (NATO reporting name 'Fullback').[13]

Navy

Development of a version for the Soviet Navy designated Su-27K (from Korabyelny - "shipborne", NATO designation 'Flanker-D') commenced not long after the development of the main land-based type. Some of the T-10 demonstrators were modified to test features of navalized variants for carrier operations. These modified demonstrators led to specific prototypes for the Soviet Navy, designated "T-10K". The T-10Ks had canards, an arresting hook and carrier landing avionics as well as a retractable inflight refueling probe. They did not have the landing gear required for carrier landings or folding wings. The first T-10K flew in August 1987 flown by the famous Soviet test pilot Viktor Pugachev (who first demonstrated the cobra manoeuvre using an Su-27 in 1989), performing test take-offs from a land-based ski-jump carrier deck on the Black Sea coast at Saky in the Ukrainian SSR. The aircraft was lost in an accident in 1988.

At the time the naval Flanker was being developed the Soviets were building their first generation of aircraft carriers and had no experience with steam catapults and did not want to delay the introduction of the carriers. Thus it was decided to use a take-off method that did not require catapults by building up full thrust against a blast deflector until the aircraft sheared restraints holding it down to the deck. The fighter would then accelerate up the deck onto a ski jump and become airborne.[14]

The production Su-27K featured the required strengthened landing gear with a two-wheel nose gear assembly, folding stabilators and wings, outer ailerons that extended further with inner double slotted flaps and enlarged leading-edge slats for low-speed carrier approaches, modified Leading Edge Root eXtension (LERX) with canards, a modified ejection seat angle, upgraded fly-by-wire, upgraded hydraulics, an arresting hook and retractable inflight refuelling probe with a pair of deployable floodlights in the nose to illuminate the tanker at night. The Su-27K began carrier trials in November 1989, again with Pugachev at the controls, on board the first Soviet aircraft carrier, called Tbilisi at the time and formal carrier operations commenced in September 1991.[15][16]

Development of the naval trainer, called the Su-27KUB (from Korabyelny Uchebno-Boyevoy - "shipborne trainer-combat"), began in 1989. The aim was to produce an airframe with dual roles for the Navy and Air Force suitable for a range of other missions such as reconnaissance, aerial refuelling, maritime strike, and jamming. This concept then evolved into the Su-27IB (Su-34 "Fullback") for the Soviet Air Force. The naval trainer had a revised forward fuselage to accommodate a side-by-side cockpit seating arrangement with crew access via a ladder in the nose-wheel undercarriage and enlarged canards, stabilisers, fins and rudders. The wings had extra ordnance hard-points and the fold position was also moved further outboard. The inlets were fixed and did not feature foreign object damage suppression hardware. The central fuselage was strengthened to accommodate 45 tonnes (99,000 pounds) maximum gross weight and internal volume was increased by 30%. This first prototype, the T-10V-1, flew in April 1990 conducting aerial refuelling trials and simulated carrier landing approaches on the Tbilisi. The second prototype, the T-10V-2 was built in 1993 and had enlarged internal fuel tanks, enlarged spine, lengthened tail and tandem dual wheel main undercarriage.[13]

Export and post-Soviet development

In 1991, the production facilities at Komsomolsk-on-Amur Aircraft Plant and Irkutsk developed export variants of the Su-27: the Su-27SK single seat fighter and Su-27UBK twin-seat trainer, (the K in both variants is Russian for "Kommercheskiy" - literally "Commercial") which have been exported to China, Vietnam, Ethiopia and Indonesia.

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Russia, the successor state, started development of advanced variants of the Su-27 including the Su-30, Su-33, Su-34, Su-35, and Su-37.

Since 1998 the export Su-27SK has been produced as the Shenyang J-11 in China under licence. The first licensed-production plane, assembled in Shenyang from Russian supplied kits, was flight tested on 16 December 1998. These licence-built versions, which numbered 100, were designated J-11A. The next model, the J-11B made extensive use of Chinese developed systems within the Su-27SK airframe.[17]

Starting in 2004, the Russian Air Force began a major update of the original Soviet Su-27 ('Flanker-B') fleet. The upgraded variants were designated Su-27SM (Russian for "Seriyniy Modernizovanniy" - literally "Serial Modernized"). This included upgrades in air-to-air capability with the R-77 missile with an active radar homing head. The modernized Su-27SM fighters belong to the 4+ generation. The strike capability was enhanced with the addition of the Kh-29T/TE/L and Kh-31P/Kh-31A ASM and KAB-500KR/KAB-1500KR smart bombs. The avionics were also upgraded. The Russian Air Force is currently receiving aircraft modernized to the SM3 standard. The aircraft’s efficiency to hit air and ground targets has increased 2 and 3 times than in the basic Su-27 variant. Su-27SM3 has two additional stations under the wing and a much stronger airframe. The aircraft is equipped with new onboard radio-electronic systems and a wider range of applicable air weapons. The aircraft’s cockpit has multifunctional displays.[18]

The Su-30 is a two-seat multi-role version developed from the Su-27UBK and was designed for export and evolved into two main variants. The export variant for China, the SU-30MKK ('Flanker-G') which first flew in 1999. The other variant developed as the export version for India, the Su-30MKI ('Flanker-H') was delivered in 2002 and has at least five other configurations.

The Su-33 is the Russian Navy version of the Soviet Su-27K which was redesignated by the Sukhoi Design Bureau after 1991. Both have the NATO designation 'Flanker-D'.

The Su-34 is the Russian derivative of the Soviet-era Su-27IB, which evolved from the Soviet Navy Su-27KUB operational conversion trainer. It was previously referred to as the Su-32MF.

The newest and most advanced version of the Su-27 is the Su-35S ("Serial"). The Su-35 was previously referred to as the Su-27M, Su-27SM2, and Su-35BM.[19]

The Su-37 is an advanced technology demonstrator derived from Su-35 prototypes, featuring thrust vectoring nozzles made of titanium rather than steel and an updated airframe containing a high proportion of carbon-fibre and Al-Li alloy.[20] Only two examples were built and in 2002 one crashed, effectively ending the program. The Su-37 improvements did however make it into new Flanker variants such as the Su-35S and the Su-30MKI.[21]

Design

.jpg.webp)

The Su-27's basic design is aerodynamically similar to the MiG-29, but it is substantially larger. The wings are attached to the center of the fuselage at the leading edge extensions, featuring a semi-delta design, with the tips cropped for missile rails or ECM pods. The fighter is also an example of a tailed delta wing configuration, retaining conventional horizontal tailplanes.[22]

The Su-27 had the Soviet Union's first operational fly-by-wire control system, based on the Sukhoi OKB's experience with the T-4 bomber project. Combined with relatively low wing loading and powerful basic flight controls, it makes for an exceptionally agile aircraft, controllable even at very low speeds and high angle of attack. In airshows the aircraft has demonstrated its maneuverability with a Cobra (Pugachev’s Cobra) or dynamic deceleration – briefly sustained level flight at a 120° angle of attack.

The naval version of the 'Flanker', the Su-27K (or Su-33), incorporates canards for additional lift, reducing takeoff distances. These canards have also been incorporated in some Su-30s, the Su-35, and the Su-37.

The Su-27 is equipped with a Phazotron N001 Myech coherent Pulse-Doppler radar with track while scan and look-down/shoot-down capability. The fighter also has an OLS-27 infrared search and track (IRST) system in the nose just forward of the cockpit with an 80–100 km (50–62 mi) range.[23]

The Su-27 is armed with a single 30 mm (1.18 in) Gryazev-Shipunov GSh-30-1 cannon in the starboard wingroot, and has up to 10 hardpoints for missiles and other weapons. Its standard missile armament for air-to-air combat is a mixture of R-73 (AA-11 Archer) and R-27 (AA-10 'Alamo') missiles, the latter including extended range and infrared homing models.

Operational history

Soviet Union and Russia

The Soviet Air Force began receiving Su-27s in June 1985.[12] The first front-line unit to receive the Su-27 was the 831st Fighter Aviation Regiment at Myrhorod Air Base, Ukrainian SSR, in November 1985.[24] It officially entered service in August 1990.[12]

On 13 September 1987, a fully armed Soviet Su-27, Red 36, intercepted a Norwegian Lockheed P-3 Orion maritime patrol aircraft flying over the Barents Sea. The Soviet fighter performed different close passes, colliding with the reconnaissance aircraft on the third pass. The Su-27 disengaged and both aircraft landed safely at their bases.[25]

These aircraft were used by the Russian Air Force during the 1992–1993 war in Abkhazia against Georgian forces. One fighter, piloted by Major Vatslav Aleksandrovich Shipko (Вацлав Александрович Шипко) was reported shot down in friendly fire by an S-75M Dvina on 19 March 1993 while intercepting Georgian Su-25s performing close air support. The pilot was killed.[26][27]

In the 2008 South Ossetia War, Russia used Su-27s to gain airspace control over Tskhinvali, the capital city of South Ossetia.[28][29]

On 7 February 2013, two Su-27s briefly entered Japanese airspace off Rishiri Island near Hokkaido, flying south over the Sea of Japan before turning back to the north.[30] Four Mitsubishi F-2 fighters were scrambled to visually confirm the Russian planes,[31] warning them by radio to leave their airspace.[32] A photo taken by a JASDF pilot of one of the two Su-27s was released by the Japan Ministry of Defense.[33] Russia denied the incursion, saying the jets were making routine flights near the disputed Kuril Islands.[30] In another encounter, on 23 April 2014 an Su-27 nearly collided with a United States Air Force Boeing RC-135U over the Sea of Okhotsk.[34]

Russia plans to replace the Su-27 and the Mikoyan MiG-29 eventually with the Sukhoi Su-57 fifth-generation multi-role twin-engine fighter.[35]

A squadron of Su-27SM3s was deployed to Syria in November 2015 as part of the Russian military intervention in the Syrian Civil War.[36][37]

A Russian Su-27 crashed over the Black Sea on 25 March 2020, in mysterious circumstances. The pilot was not found,[38] after a large-scale rescue effort hampered by inclement weather involving four helicopters, 11 civilian and military vessels, and several drones. The plane's last location was some 50 kilometers from the city of Feodosia.[39]

China

China was the first foreign operator of Su-27 and the only country to acquire the fighter before the fall of the Soviet Union. The deal, known as the '906 Project' in China,[40] marked a leap in Chinese aviation capability in the 1990s.[41] Discussion of the aircraft purchase began in 1988 when the Soviet Union offered China fourth-generation fighters like MiG-29. However, the Chinese negotiator insisted on purchasing the Su-27, the most sophisticated fighter Soviets had at the time. The sales were approved in December 1990, with three fighters delivered to China before the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991.[41] Russia completed the contract and allowed China to manufacture the Su-27 domestically, where the aircraft is designated as J-11.[41]

The earliest batch of Su-27s was stationed at the Wuhu air base in the early 1990s.[42] In the next two decades, 78 Flankers were delivered under three separate contracts by the Russian KnAAPO and IAPO plants. Delivery of the aircraft began in February 1991 and finished by September 2009. The first contract was for 20 Su-27SK and 4 Su-27UBK aircraft. In February 1991, a Su-27 performed a flight demonstration at Beijing's Nanyuan Airport. Chinese Su-27 pilots described its performance as "outstanding" in all aspects and flight envelopes. The official induction to service with the PLAAF occurred shortly thereafter. China found some of the aircraft delivered were Su-27UBs that had been built in 1989 for the Soviet Union but never delivered. Russia delivered 2 more Su-27UBKs to China as a compensation.[40]

Differences in the payment method delayed the signing of the second, identical contract. For the first batch, 70% of the payment had been made in barter transactions with light industrial goods and food. The Russian Federation argued that future transactions should be made in US dollars. In May 1995, Chinese Central Military Commission Vice Chairman Liu Huaqing visited Russia and agreed to the demand, on the condition that the production line of the Su-27 be imported. The contract was signed the same year. Delivery of the final aircraft from the second batch, which consisted of 16 Su-27SKs and 8 Su-27UBKs, occurred in July 1996. In preparation for the expanding Su-27 fleet, the PLAAF sought to augment its trainer fleet.[43]

On 3 December 1999, a third contract was signed, this time for 28 Su-27UBKs. All 76 of the aircraft featured strengthened airframe and landing gear – the result of the PLAAF demands air-ground capability. As a result, the aircraft is capable of employing most of the conventional air-to-ground ordnance produced by Russia. Maximum take-off weight (MTOW) increased to 33,000 kg (73,000 lb). As is common for Russian export fighters, the active jamming device was downgraded; Su-27's L005 ECM pod was replaced with the L203/L204 pod. Furthermore, there were slight avionics differences between the batches. The first batch had N001E radar, while the later aircraft had N001P radar, capable of engaging two targets at the same time. Additionally, ground radar and navigational systems were upgraded. The aircraft are not capable of deploying the R-77 "Adder" missile due to a downgraded fire control system,[43] except for the last batch of 28 Su-27UBKs.[40]

At the 2009 Farnborough Airshow, Alexander Fomin- Deputy Director of Russia's Federal Service for Military-Technical Co-operation confirmed the existence of an all-encompassing contract and ongoing licensed production of Su-27 variants by China. The aircraft was being produced as the Shenyang J-11.[44]

Ethiopia

Ethiopian Su-27s shot down two Eritrean MiG-29s and damaged another one during the Eritrean-Ethiopian War[45][46] in February 1999 and destroyed another two in May 2000.[46][47] The Su-27s were also used in combat air patrol (CAP) missions, suppression of air defense, and providing escort for fighters on bombing and reconnaissance missions.[48] The Ethiopian Air Force (EtAF) used their Su-27s to deadly effect in Somalia during late 2000s and 2010s, bombing Islamist garrisons and patrolling the airspace. The Su-27 has replaced the aging Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21, which was the main air superiority fighter of the EtAF between 1977 and 1999.[49] Ethiopian government used its Su-27s for bombing targets during the Tigray War. Ethiopian Su-27s were depicted armed with OFAB-250 unguided bombs and over the skies of Mekelle. On 25 August 2022, Ethiopian authorities claimed an An-26 was intercepted and then shot down by an EtAF Su-27, scrambled to investigate the airspace violation incoming from Sudan.[50]

Angola

The Su-27 entered Angolan service in mid-2000 during the Angolan Civil War. It is reported that one Su-27 in the process of landing, was shot down by 9K34 Strela-3 MANPADs fired by UNITA forces on 19 November 2000.[45][51]

Indonesia

Four Indonesian Flanker-type fighters including Su-27s participated for the first time in the biennial Exercise Pitch Black exercise in Australia on 27 July 2012. Arriving at Darwin, Australia, the two Su-27s and two Sukhoi Su-30s were escorted by two Australian F/A-18 Hornets of No. 77 Squadron, Royal Australian Air Force.[52] Exercise Pitch Black 12 was conducted from 27 July through 17 August 2012, and involved 2,200 personnel and up to 94 aircraft from Australia, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, New Zealand and the United States.[53]

Ukraine

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The Ukrainian Air Force inherited about 66-70 Su-27 aircraft after the collapse of the Soviet Union.[54] Lack of funds in addition to the Su-27's high maintenance requirements led to a shortage of spare parts and inadequate servicing with approximately 34 in service as of 2019.[55][56][57] Years of underfunding meant that the air force has not received a new Su-27 since 1991. Between 2007 and 2017, as many as 65 combat jets were sold abroad,[58] including nine Su-27s.[59] In 2009, amid declining relations with Russia, the Ukrainian Air Force began to have difficulty obtaining spare parts from Sukhoi.[59] Only 19 Su-27s were serviceable at the time of the Russian annexation of Crimea and subsequent War in Donbas in 2014.[59] Following the Russian invasion, Ukraine increased its military budget, allowing stored Su-27s to be returned to service.[58][60]

The Zaporizhzhya Aircraft Repair Plant "MiGremont" in Zaporizhzhia began modernizing the Su-27 to NATO standards in 2012, which involved a minor overhaul of the radar, navigation and communication equipment. Aircraft with this modification are designated Su-27P1M and Su-27UB1M. The Ministry of Defence accepted the project on 5 August 2014,[60] and the first two aircraft were officially handed over to the 831st Tactical Aviation Brigade in October 2015.[61]

In 2014 during the Annexation of Crimea, a Ukrainian Air Force Su-27 was scrambled to intercept Russian fighter jets over Ukraine's airspace over the Black Sea on 3 March.[62] With no aerial opposition and other aircraft available for ground attack duties, Ukrainian Su-27s played only a small role in the war in Donbas until 24 February 2022. Ukrainian Su-27s were recorded performing low fly passes and were reported flying top cover, combat air patrols and eventual escort or intercept of civil aviation traffic over Eastern Ukraine.[63][64] Videos taken of low-flying Su-27s involved in the operation revealed they were armed with R-27 and R-73 air-to-air missiles.[65]

There were two fatal crashes involving Ukrainian Su-27s in 2018.[57] On 16 October, a Ukrainian Su-27UB1M flown by Colonel Ivan Petrenko crashed during the Ukraine-USAF exercise "Clear Sky 2018" based at Starokostiantyniv Air Base. The second seat was occupied by Lieutenant Colonel Seth Nehring, a pilot of the 144th Fighter Wing of the California Air National Guard. Both pilots died in the crash, that happened about 5:00 p.m. local time in the Khmelnytskyi province of western Ukraine.[66][67] On 15 December, an Su-27 crashed on final approach about 2 km (1 mi) from Ozerne Air Base in Zhytomyr Oblast, after performing a training flight. Major Fomenko Alexander Vasilyevich was killed.[68]

On 29 May 2020, Ukrainian Su-27s took part in the Bomber Task Force in Europe with B-1B bombers for the first time in the Black Sea region.[69] On 4 September 2020, three B-52 bombers from the 5th Bomb Wing, Minot Air Force Base, North Dakota, conducted vital integration training with Ukrainian MiG-29s and Su-27s inside Ukraine’s airspace.[70]

Russo-Ukrainian War

Russian invasion of Ukraine

The Su-27 was used by both sides in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[71] On 24 February 2022, a Ukrainian Su-27 and a refueling vehicle were burned out by fire after a Russian attack on Ozerne Air Base in Zhytomyr District during the first day of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[72] The next day, another Su-27 was shot down in Kyiv by a Russian S-400 system[73] and was recorded by residents on their cell phones and published on Twitter;[74] its pilot, Colonel Oleksandr Oksanchenko, was killed.[75] A third Su-27 was reported lost by Ukrainian officials over Kropyvnytskyi, in central Ukraine; its pilot was killed.[76]

On 7 May 2022, a pair of Ukrainian Su-27s conducted a high-speed, low-level bombing run on Russian-occupied Snake Island; the attack was captured on film by a Bayraktar TB2 drone.[77]

On 7 June 2022, a Ukrainian Su-27, bort number 38 blue, was shot down while flying at low altitude near Orikhiv in Zaporizhzhia Oblast. The aircraft was reportedly destroyed either by an enemy air-to-air missile or due to friendly fire.[78][79]

On 21 August 2022, a Ukrainian Su-27 was reported lost in combat. The pilot died.[80][81]

In September 2022, a Ukrainian Su-27 has been spotted carrying out SEAD mission with American made AGM-88 HARM anti-radiation missiles.[82]

On 13 October 2022, one Ukrainian Su-27 from the 39th Tactical Aviation Brigade was lost during a combat mission in Poltava Oblast, the pilot died.[83][84]

On 10 March 2023, A Russian Su-27 was damaged in a partisan attack on Uglovoye airfield in Primorsky Krai, Russia. The video of a burning airplane was posted by the Freedom of Russia Legion.[85]

On 14 March 2023 Black Sea drone incident, a Russian Su-27 intercepted an American MQ-9 Reaper drone and performed several passes dumping fuel on to it, until colliding with it, causing the drone to crash into the Black Sea.[86]

Variants

Soviet era

_DD-SD-99-06153.jpg.webp)

- T-10 ("Flanker-A")

- [87] Initial prototype configuration.

- T-10S ("Flanker-A")

- [87] Improved prototype configuration, more similar to production spec.

- P-42

- Special version built to beat climb time records. The aircraft had all armament, radar and paint removed, which reduced weight to 14,100 kg (31,100 lb). It also had improved engines. Similar to the US F-15 Streak Eagle project. Between 1986 and 1988, it established and took several climb records from the Streak Eagle. Several of these records (such as time to climb to 3000 m, 6000 m, 9000 m, and 12000 m) still stands current as of 2019.[88][89]

- Su-27 ("Flanker-A")

- [87] Pre-production series built in small numbers with AL-31 engine.

- Su-27S (Su-27 / "Flanker-B")

- [87][90] Initial production single-seater with improved AL-31F engine. The "T-10P".

- Su-27P (Su-27 / "Flanker-B")

- [87][90] Standard version but without air-to-ground weapons control system and wiring and assigned to Soviet Air Defence Forces units. Often designated Su-27 without -P.[91]

- Su-27UB ("Flanker-C")

- [87][90] Initial production two-seat operational conversion trainer.

- Su-27K (Su-33 / "Flanker-D")

- [87][90] Carrier-based single-seater with folding wings, high-lift devices, and arresting gear, built in small numbers. They followed the "T-10K" prototypes and demonstrators.

- Su-27KUB (Su-33UB)

- Two-seat training-and-combat version based on the Su-27K and Su-27KU, with a side-by-side seating same as Su-34. One prototype built.

- Su-27M (Su-35/Su-37 / "Flanker-E/F")

- [92][93] Improved demonstrators for an advanced single-seat multi-role Su-27S derivative. These also included a two-seat "Su-35UB" demonstrator.

- Su-27PU (Su-30 / "Flanker-C")

- [87][90] Two-seat version of the Su-27P interceptor, designed to support other single-seat Su-27P, MiG-31 and other interceptor aircraft in PVO service, with tactical data. The model was later renamed to Su-30, and modified into a multi-role fighter mainly for export market, moving away from the original purpose of the aircraft.

- Su-32 (Su-27IB)

- Two-seat dedicated long-range strike variant with side-by-side seating in "platypus" nose. Prototype of Su-32FN and Su-34.

Post-Soviet era

- Su-27PD ("Flanker-B")

- Single-seat demonstrator with improvements such as inflight refuelling probe.

- Su-30M/MK ("Flanker-H")

- Next-generation multi-role two–seat fighter. A few Su-30Ms were built for Russian evaluation in the mid-1990s, though little came of the effort. The Su-30MK export variant was embodied as a series of two demonstrators of different levels of capability. Versions include Su-30MKA for Algeria, Su-30MKI for India, Su-30MKK for the People's Republic of China, and Su-30MKM for Malaysia.[94][95]

- Su-27SK ("Flanker-B")

- [87][90] Export version of the Su-27S, with a reinforced landing gear allowing for a 33 tonnes maximum take-off weight, and a N001M radar with additional air-to-ground modes.[96] Exported to China in 1992-1996 and developed into the Shenyang J-11. It was also sold to Indonesia in 2003. Indonesian Su-27SKs are equipped with an in-flight refuelling probe.[96]

- Su-27KI / Su-30KI

- Single-seat demonstrator built in anticipation of an Indonesian order in 1997, based on a Su-27SK. It included an in-flight refuelling probe, and a N001M radar with additional functions allowing for the use of the R-77 missile. That order never came however, due to an embargo caused by the Indonesian occupation of East Timor.[96] Later converted to Su-27SKM in 2002.[97]

- Shenyang J-11

- Chinese derivative of the Su-27SK.

- Su-27UBK ("Flanker-C")

- [87][90] Export Su-27UB two-seater.

- Su-27SKM

- Single-seat multi-role fighter for export. It is a derivative of the Su-27SK but includes upgrades such as advanced cockpit, more sophisticated self-defense electronic countermeasures (ECM) and an in-flight refuelling system.[98]

- Su-27UBM

- Comparable upgraded Su-27UB two-seater.

- Su-27SM ("Flanker-E")

- Mid-life upgrade for the Russian Su-27 fleet. It includes new multi-function displays replacing analog flight instruments, improvements to the navigation system, a new fire-control system with slightly improved radar and electro-optical sighting system, and a more advanced mission computer. This allows for use of the radar in synthetic-aperture terrain mapping mode, as well as detection of maritime targets. Contrary to the basic Su-27 variants, the Su-27SM can use guided air-to-ground ordnance, including Kh-29 and Kh-31 missiles, and laser-guided bombs, as well as the R-77 air-to-air missile. The SPO-15 Beryoza is replaced by the Pastel radar warning receiver, and the Sorbtsiya wingtip jamming pods are replaced by the more modern Khibiny. 24 Su-27SMs also received slightly uprated engines.[71]

- Su-27SM2 ("Flanker-J")

- 4+ gen block upgrade for Russian Su-27, featuring some technology of the Su-35BM; it includes Irbis-E radar, and uprated engines and avionics.

- Su-27SM3 ("Flanker-J Mod")

- [99] Increased maximum takeoff weight (+3 tonnes), AL-31F-M1 engines, fully glass cockpit.[100]

- Su-27UB1M

- Ukrainian modernized version of the Su-27UB.

- Su-27S1M

- Ukrainian modernized version of the Su-27S.

- Su-27P1M

- Ukrainian modernized version of the Su-27P.

- Su-35BM/Su-35S ("Flanker-M")

- [92][93] Also named the "Last Flanker" is latest development from Sukhoi Flanker family. It features improved thrust vectoring AL-41F1S engines, new avionics, N035 Irbis-E radar and reduced radar cross-section.

Operators

Current operators

Angola

Angola- People's Air and Air Defence Force of Angola – Seven Su-27s in service as of January 2013.[101] Three were bought from Belarus in 1998. Received a total of eight.[102] One was reportedly shot down on 19 November 2000 by a 9K34 Strela-3 MANPADS during the Angolan Civil War.[103]

China

China- People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) – 78 Su-27 delivered between 1990 and 2010. 32 Su-27UBK are in service as of 2022.[104]

Eritrea

Eritrea- Eritrean Air Force[105] ordered 2 during the Eritrean War of Independence.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia- Ethiopian Air Force – up to 17 Su-27S, Su-27P, Su-27UB sourced second–hand from Russia in two different batches: 9 starting from 1998 and 8 starting from 2002.[106] Some crashed over the years.[107]

Indonesia

Indonesia- Indonesian Air Force (TNI - AU or Tentara Nasional Indonesia - Angkatan Udara) – two Su-27SK and three Su-27SKM fighters in service.[96]

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan- Military of Kazakhstan – 20 Su-27/Su-27BM2, 3 Su-27UB/UBM2

.jpg.webp)

Russia

Russia- Russian Aerospace Forces – 101 Su-27s in service as of 2021.[108] 359 Su-27 aircraft, including 225 Su-27s, 70 Su-27SMs, 12 Su-27SM3s, and 52 Su-27UBs were in service as of January 2014.[109] A modernization program began in 2004.[110][111][112] Half of the Su-27 fleet had reportedly been modernized in 2012.[113] The Russian Aerospace Forces were receiving aircraft modernized to the SM3 standard as of 2018.[114][115][116][117]

- Russian Navy – 53 Su-27s in use as of January 2014[109]

Ukraine

Ukraine- Ukrainian Air Force – 70 Su-27s in inventory.[118] It had 34 Su-27s in service as of March 2019.[58]

United States

United States- Two Su-27s were delivered to the U.S. in 1995 from Belarus.[119][120] Two more were bought from Ukraine in 2009 by a private company, Pride Aircraft to be used for aggressor training for U.S. pilots. They have been spotted operating over Area 51 for evaluation and training purposes.[121]

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan- Military of Uzbekistan – 34 Su-27s in use as of January 2013[101]

Vietnam

Vietnam- Vietnam People's Air Force – 9 Su-27SKs and 3 Su-27UBKs in use as of January 2013[101]

Former operators

.svg.png.webp) Belarus

Belarus- Belarusian Air Force inherited 23-28 Su-27s from the former 61st Fighter Aviation Regiment of the Soviet Union.[119] They had 22 in service as of December 2010.[122] Nine Su-27s were sold to Angola in 1998. Belarus had operated 17 Su-27P and 4 Su-27UBM1 aircraft before their retirement in December 2012.[102][123][124]

Soviet Union

Soviet Union- Soviet Air Force and Soviet Air Defence Forces. Passed to different successor nations in 1991.

Private ownership

According to the U.S. FAA there are two privately owned Su-27s in the U.S.[125] Two Su-27s from the Ukrainian Air Force were demilitarised and sold to Pride Aircraft of Rockford, Illinois. Pride Aircraft modified some of the aircraft to their own desires by remarking all cockpit controls in English and replacing much of the Russian avionics suite with Garmin, Bendix/King, and Collins avionics. The aircraft were both sold to private owners for approximately $5 million each.[126]

On 30 August 2010, the Financial Times claimed that a Western private training support company ECA Program placed a US$1.5 billion order with Belarusian state arms dealer BelTechExport for 15 unarmed Su-27s (with an option on 18 more) to organize a dissimilar air combat training school in the former NATO airbase in Keflavik, Iceland, with deliveries due by the end of 2012.[127][128] A September 2010 media report by RIA Novosti, the state-owned news agency, questioned the existence of the agreement.[129] No further developments on such a plan have been reported by 2014, while a plan for upgrading and putting the retired Belarusian Air Force Su-27 fleet back to service was reported in February 2014.[130]

Notable accidents

- 9 September 1990: A Soviet Su-27 crashed at the Salgareda airshow in 1990 after pulling a loop at too low an altitude. The Lithuanian pilot, Rimantas Stankevičius, and a spectator were killed.[131][132]

- 12 December 1995: Two Su-27s and an Su-27UB of the Russian Knights flight demonstration team crashed into terrain outside of Cam Ranh, Vietnam, killing four team pilots. Six Su-27s and an Ilyushin Il-76 support aircraft were returning from a Malaysian airshow. The aircraft were flying in echelons right and left of the Il-76 on their way to Cam Ranh for refueling. During the landing approach, the Il-76 passed too close to the terrain and the three right-echelon Su-27s crashed. The other aircraft landed safely at Cam Ranh. The cause was controlled flight into terrain; contributing factors were pilot error, mountainous terrain and poor weather.[133]

- 27 July 2002: A Ukrainian Su-27 crashed while performing an aerobatics presentation, killing 77 spectators in what is now considered the deadliest air show disaster in history. Both pilots ejected and suffered only minor injuries.[134]

- 15 September 2005: Russian fighter Su-27 crashed near the city of Kaunas, Lithuania. The pilot ejected and wasn't hurt. Investigation concluded, that main cause for crash was pilot's incompetence.[135]

- 16 August 2009: While practicing for the 2009 MAKS Airshow, two Su-27s of the Russian Knights collided in mid-air above Zhukovsky Airfield, south-east of Moscow, killing the Knights' leader, Igor Tkachenko. One of the jets crashed into a house and started a fire.[136] A probe into the crash was launched; according to the Russian Defense Ministry the accident may have been caused by a "flying skill error".[136]

- 30 August 2009: A Belarusian Su-27UBM (Number black 63) crashed while performing at the Radom Air Show.[137]

- 14 March 2023: A Russian Su-27 flew near a USAF MQ-9 UAV operating in international airspace over the Black Sea, dumped fuel on it (presumably to try to set it alight), and finally collided with the propellor which caused the USAF operator to ditch the UAV into the sea.[138]

Aircraft on display

- 36911031003 – Su-27PD on static display at the Central Armed Forces Museum in Moscow.[139][140]

- 96310408027 – Su-27UB on static display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.[141][142]

Specifications (Su-27SK)

Data from [143] Sukhoi,[144] KnAAPO,[145] Deagel.com,[146] Airforce-Technology.com[147]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 21.9 m (71 ft 10 in)

- Wingspan: 14.7 m (48 ft 3 in)

- Height: 5.92 m (19 ft 5 in)

- Wing area: 62 m2 (670 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 16,380 kg (36,112 lb)

- Gross weight: 23,430 kg (51,654 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 30,450 kg (67,131 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 9,400 kg (20,723.5 lb) internal[144]

- Powerplant: 2 × Saturn AL-31F afterburning turbofan engines, 75.22 kN (16,910 lbf) thrust each dry, 122.6 kN (27,600 lbf) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 2,500 km/h (1,600 mph, 1,300 kn) / M2.35 at altitude

- 1,400 km/h (870 mph; 760 kn) / M1.13 at sea level

- Range: 3,530 km (2,190 mi, 1,910 nmi) At altitude

- 1,340 km (830 mi; 720 nmi) at sea level

- Service ceiling: 19,000 m (62,000 ft)

- g limits: +9

- Rate of climb: 300 m/s (59,000 ft/min) [148]

- Wing loading: 377.9 kg/m2 (77.4 lb/sq ft) With 56% fuel

- 444.61 kg/m2 (91.1 lb/sq ft)

- Thrust/weight: 1.07 with 56% internal fuel; 0.91 with full fuel

Armament

- Guns: 1 × 30 mm Gryazev-Shipunov GSh-30-1 autocannon with 150 rounds

- Hardpoints: 10 external pylons[144] with a capacity of up to 4,430 kg (9,770 lb)[144], with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets:

- Missiles:

- 6 × R-27R/ER/T/ET/P/EP air-to-air missiles

- 6 × R-73E AAMs

- 4 x AGM-88 HARM anti-radiation missile (Ukrainian AF)[149]

- Bombs:

- Rockets:

Avionics

- N001E radar

- Phazotron Zhuk-MSE radar

- Phazotron Zhuk-MSFE radar

- Irbis-E passive electronically scanned array radar for Su-27SM2/SM3

- OEPS-27 electro-optical targeting system

- SPO-150 Radar Warning Receiver

- OEPS-27 IRST[150]

- Shchel-3UM Helmet-mounted display system

Notable appearances in media

See also

Related development

- Sukhoi Su-30

- Sukhoi Su-33

- Sukhoi Su-34

- Sukhoi Su-35

- Sukhoi Su-37

- Shenyang J-11

- Shenyang J-15

- Shenyang J-16

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

- References

- ↑ Russia Air Force Handbook. World Strategic and Business Information Library. Washington, D.C.: International Business Publications USA. 2009. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-43874-019-5.

- ↑ Kopp, Dr. Carlo (May 1990). "Fulcrum and Flanker: The New Look in Soviet Air Superiority". Australian Aviation. 1990 (May). Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015 – via Air Power Australia.

- 1 2 Spick, Mike, ed. (2000). "The Flanker". Great Book of Modern Warplanes. Osceola, WI: MBI Publishing. ISBN 0-7603-0893-4.

- ↑ Hillebrand, Niels. "Aircraft - Sukhoi Su-27 Flanker Historical Events & Key Dates". Milavia. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2011.

- ↑ "Prototype of Su-27 and whole Flanker family – T-10 Flanker A". SU-27 Flanker.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- ↑ "Prototype of Su-27 and whole Flanker family – T-10 Flanker A". Su-27 Flanker.com. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Kopp, Dr. Carlo (7 January 2007). "Sukhoi Flankers: The Shifting Balance of Regional Air Power (Technical Report APA-TR-2007-0101)". Air Power Australia: 1. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ "The fastest climb in aviation history. Climbing time record of the Su-27 to an altitude of 12 km". YouTube. 5 July 2020.

- ↑ "40 Years Ago, 'Streak Eagle' Smashed Records for 'Time to Climb'". United Technologies Corp. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ "P-42 Record Flanker". ProPro Group. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ Winchester, Jim (2012). Jet fighters : inside & out. New York: Rosen Pub. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-44885-982-5. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Airplanes - Military Aircraft - Su-27SÊ - Historical background". Sukhoi Company (JSC). Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1 2 Kopp, Dr. Carlo (April 2012). "Sukhoi Su-34 Fullback: Russia's New Heavy Strike Fighter (Technical Report APA-TR-2007-0108)". Air Power Australia: 1. Archived from the original on 17 March 2015. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ↑ Goebel, Greg. "[1.0] First-Generation Su-27s - [1.5] Naval Su-27K (Su-33)". AirVectors.net. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ Kopp, Dr Carlo (25 June 2008). "Sukhoi Su-33 and Su-33UB Flanker D Shenyang J-15 Flanker D (Technical Report APA-TR-2008-0603)". Air Power Australia: 1. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ "Kuznetsov class heavy aviation cruiser". Military-Today.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ Kopp, Dr Carlo (7 April 2012). "PLA-AF and PLA-N Flanker Variants (Technical Report APA-TR-2012-0401)". Air Power Australia: 1. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ "Russian Air Force sets up new Su-27SM3 wing". AirRecognition.com. November 2018. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ↑ Katz, Dan. "Program Dossier - Sukhoi Flanker" (PDF). Aviation Week. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ Pike, John (11 March 1999). "Su-37". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ "Su-37 Flanker-F Fighter, Russia". Airforce-Technology.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ "Su-27 FLANKER". www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ↑ "Sukhoi Su-27SK Flanker-B". U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. 2004. Archived from the original on 29 April 2007.

- ↑ Trendafflovski, Vladimir (21 March 2019). "Ukrainian Su-27 Flankers on the front line". key.aero. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ↑ Cooper, Tom (29 September 2003). "Bear Hunters, Part 3: Collision with Flanker". Air Combat Information Group Database. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Aminov, Said (2008). "Georgia's Air Defense in the War with South Ossetia". Moscow Defense Brief. No. 3. Archived from the original on 11 July 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Cooper, Tom (29 September 2003). "Georgia and Abkhazia, 1992-1993: the War of Datchas". Air Combat Information Group Database. Archived from the original on 3 March 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "Грузинские войска отступают из Цхинвали" [Georgian troops retreat from Tskhinvali]. Lenta.ru (in Russian). 8 August 2008. Archived from the original on 30 October 2008.

- ↑ "Российские самолеты бомбят позиции грузинских войск" [Russian planes are bombing Georgian army positions]. Lenta.ru (in Russian). 8 August 2008. Archived from the original on 26 October 2008.

- 1 2 "Russian fighter jets 'breach Japan airspace'". BBC News. 7 February 2013. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ "Japan accuses Russian jets of violating airspace". Dawn. 7 February 2013. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ "Japan scrambles fighter jets as Russian warplanes intrude into airspace". Kuwait News Agency (KUNA). 7 February 2013. Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, Mari (7 February 2013). "Japan says 2 Russian fighters entered its airspace". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ↑ Gertz, Bill (3 June 2014). "Russian jet nearly collides with U.S. surveillance aircraft in 'reckless' intercept in Asia". The Washington Free Beacon. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- ↑ "Sukhoi T-50 PAK FA Stealth Fighter, Russia". Airforce-Technology.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ Brown, Daniel (26 February 2018). "These are the 11 types of Russian military jets and planes known to be stationed in Syria". Business Insider.

- ↑ "Su-27SM3 seen in Syria". Weaponews.com. 29 June 2017.

- ↑ "Rocket's engine blast caused Su-27 jet's crash in Crimea in March 2020". TASS. 30 August 2020.

- ↑ "Russian pilot missing after military jet crashes into Black Sea". Deutsche Welle. 26 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 "考据的魅力——教你如何识别中国苏-27系列战机" [The charm of textual research - teach you how to identify the Chinese Su-27 series fighters]. SINA (in Chinese). 20 August 2014. Archived from the original on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Final Gift From the Soviets: How China Received Three of the USSR's Top Fighters Weeks Before the Superpower Collapsed". military watch magazine. 14 August 2022.

- ↑ E. Tyler, Patrick (7 February 1996). "China to Buy 72 Advanced Fighter Planes From Russia". New York Times.

- 1 2 Wei, Bai (May 2012). "A Flanker by any other name". Air Forces Monthly (290): 72–77.

- ↑ Rupprecht, Andreas (December 2011). "China's 'Flanker' gains momentum. Shenyang J-11 update". Combat Aircraft Monthly. 12 (12): 40–42.

- 1 2 "Su-27 operations". Milavia. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- 1 2 "Different African Air-to-Air Victories". Air Combat Information Group. 2 September 2003. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010.

- ↑ Magnus, Allan (16 January 2004). "Air-to-air claims during Ethiopian/Eritrean Conflicts in 1999-2000". Air Aces. Archived from the original on 24 September 2002. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- ↑ "ke bahru be chilfa" (Ethiopian Air Force graduation publication, May 2007), pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Kyzer, Jonathan; Cooper, Tom & Ruud, Frithjof Johan (17 January 2003). "Air War between Ethiopia and Eritrea, 1998-2000". Dankalia.com. Air Combat Information Group. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ↑ "Shot down or not shot down? Assessing Ethiopian Air Force claims". gerjon.substack.com.

- ↑ "Arms Trade Database for January-March 2001". Moscow Defense Brief. No. 2. 2001. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- ↑ "Indonesian Sukhois Arrive at Darwin for Pitch Black 2012". Defense Update. 27 July 2012. Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "Exercise Pitch Black 2012 concludes". Airforce Technology. 19 August 2012. Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Gordon & Davison (2006), p. 100.

- ↑ Dixon, Robyn (29 July 2002). "Ukraine Arrests 4 in Air Show Crash". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ↑ "Sukhoi Su-27: Dazzling Russian fighter". BBC News. 28 July 2002. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Rust Bucket Fleet? How Ukraine's Ageing Su-27 Fleet Would Fare Against Russia's Elite New Air Superiority Fighters". Military Watch. 2 January 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 Ponomarenko, Illia (15 March 2019). "Ukraine's Air Force rebuilds amidst war". Kyiv Post. Kyiv, Ukraine. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- 1 2 3 Romanenko, Valeriy (October 2020). "The Russian Jet That Fights for Both Sides". Air & Space. Translation by Dan Zamansky. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- 1 2 "Su-27 Flanker Operators List". Milavia. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ↑ "Poroshenko conveys two Su-27 planes to Air Force pilots in Zaporizhia, takes off in one of them". UNIAN. 15 October 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ↑ "Russian fighter jets violated Ukraine's air space – ministry". Reuters UK. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ↑ "[Photo] Ukrainian Air Force Su-27 Flanker heavily armed for Combat Air Patrol". The Aviationist. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 6 May 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ "All flights, including Malaysian B777, were being escorted by Ukrainian Su-27 Flanker jets over Eastern Ukraine". The Aviationist. 21 July 2014. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ "Ukrainian Su-27 Flanker reportedly shot down during special operation against separatists". The Aviationist. 15 April 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- ↑ "US serviceman among two killed in Ukrainian fighter jet crash". Space Daily. 17 October 2018. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018.

- ↑ Insinna, Valerie (17 October 2018). "California guardsman killed in Ukrainian Su-27 crash". Air Force Times.

- ↑ "Accident Sukhoi Su-27 55 blue, 15 Dec 2018". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ↑ Correll, Diana Stancy (29 May 2020). "B-1Bs complete Bomber Task Force mission with Ukrainian, Turkish aircraft for the first time". Air Force Times. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ "U.S. Air Force B-52s Integrate with Ukrainian Fighters". United States European Command. 4 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- 1 2 Newdick, Thomas (7 December 2022). "Our First Detailed Look At Russian Su-27 Flanker Jets In The Ukraine War". The Drive.

- ↑ "Пожежники загасили пожежу на аеродромі біля Житомира" [Firefighters extinguished the fire at the airport near Zhytomyr]. Galychyna (in Ukrainian). 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022.

- ↑ "Legendary Ukrainian display pilot known as Grey Wolf dies in combat". The Week. 1 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ↑ "Video shows explosion after fighter jet shot down, official says". CNN. 25 February 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ↑ Leone, Dario (1 March 2022). "Colonel Oleksandr "Grey Wolf" Oksanchenko, the Ukrainian Air Force Su-27 Flanker display pilot between 2013-2018, Killed in an Air Battle on Friday Night". The Aviation Geek Club.

- ↑ Trevithick, Joseph (2 March 2022). "Russian Amphibious Assault Ship Armada Seen Off Crimea As Fears Of Odessa Beach Landing Grow". The Drive.

- ↑ Stetson Payne (7 May 2022). "Ukraine Strikes Back: Su-27s Bomb Occupied Snake Island In Daring Raid". The Drive. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ↑ "Possible air-to-air shootdown captured on camera in Ukraine". aerotime.aero. 6 June 2022.

- ↑ "ASN Wikibase Occurrence # 279043". Aviation Safety Network. 6 June 2022.

- ↑ "Тяжка втрата: під час виконання завдання розбився житомирський льотчик" (in Ukrainian). 24 August 2022.

- ↑ "ASN Wikibase Occurrence # 282655". aviation-safety.net. 21 August 2022.

- ↑ @UAWeapons (9 September 2022). "So far, we have only seen AGM-88 HARM in use with Ukrainian MiG-29 jets" (Tweet). Retrieved 9 September 2022 – via Twitter.

- ↑ "ASN Wikibase Occurrence # 296372". aviation-safety.net. 11 October 2022.

- ↑ "У Чернігові провели в останню путь штурмана авіації полковника Олега Шупіка". Suspilne (in Ukrainian). 14 October 2022.

- ↑ "ASN Wikibase Occurrence # 309095". Aviation Safety Network. 10 March 2023.

- ↑ "Video captures moment Russian fighter rammed USAF MQ-9 drone". AeroTime. 16 March 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Flanker: The Russian Jet That Spawned Many New Versions". 14 May 2018.

- ↑ "Records". World Air Sports Federation. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- ↑ "P-42 Streak Flanker prototype (T-10) – record breaker". Su-27 Flanker. 22 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kopp, Carlo (27 January 2014). "PLA-AF and PLA-N Flanker Variants". p. 1.

- ↑ "Su-27 Flanker Variants Overview". Milavia. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011.

- 1 2 "Su-35 Flanker-E Multirole Fighter". 9 April 2021.

- 1 2 "Su-35S Flanker E". 14 May 2018.

- ↑ "Russia Has Big Plans for the Sukhoi Su-30SM Flanker-H Fighter". 24 September 2018.

- ↑ "Su-30M Flanker-H Air-Superiority Fighter". 23 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "[Dossier] Le Flanker en Indonésie". Red Samovar. 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Sukhoi Su-30 story in colours. Sukhoi Su-30 fighter worldwide camouflage and painting schemes. Prototypes, experimental planes, variants, serial and licensed production, deliveries, units, numbers. Russia, India, China, Malaysia, Venezuela, Belarus, Ukraine, Algeria, Vietnam, Eritrea, Angola, Uganda".

- ↑ "The SU-27SKM Single-Seat Multirole Fighter". KnAAPO. 2006. Archived from the original on 13 March 2008.

- ↑ "Aircraft Nomenclature (part 1): Russia and China". 5 November 2020. Archived from the original on 24 October 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ↑ "Sukhoi Company has performed the state contract on delivery of new multi-role Su-27SM3 fighters to the Russian air forces". Russian Aviation. 23 December 2011. Archived from the original on 23 November 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 "World Military Aircraft Inventory". 2013 Aerospace: Aviation Week and Space Technology, January 2013.

- 1 2 "Су-27 сняты с вооружения в Белоруссии" [Su-27s disarmed in Belarus]. BMPD (in Russian). 15 December 2012. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ↑ Hillebrand, Niels. "Sukhoi Su-27 Flanker Operators". Milavia. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ International Institute for Strategic Studies: The Military Balance 2022, p.261

- ↑ "World Air Forces 2021". FlightGlobal. 4 December 2020. Archived from the original on 10 February 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ↑ "Trade Registers". SIPRI.

- ↑ Kenyette, Patrick (13 October 2019). "Ethiopian Air Force Sukhoi Su-27 fighter jet crash, no survivors". African Military. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019.

- ↑ The Military Balance, International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), 2021

- 1 2 "World Military Aircraft Inventory". 2014 Aerospace: Aviation Week and Space Technology, January 2014.

- ↑ "Су-27 предлагают списать" [Su-27 is proposed to be decommissioned]. Samara Airlines (in Russian). 18 June 2011. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "ВВС России получат восемь новых истребителей Су-27СМ" [Russian Air Force to receive eight new Su-27SM fighters]. Lenta.ru (in Russian). 3 November 2011. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Air Forces Monthly, December 2010.

- ↑ "Авиапарк Су-27 ВВС РФ модернизирован более чем на 50%, до конца года ожидается поступление первых шести серийных Су-35" [The Su-27 fleet of the Russian Air Force has been modernized by more than 50%, the first six serial Su-35s are expected to arrive by the end of the year]. Center for Analysis of the World Arms Trade (in Russian). 13 March 2012. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "Летчики ЮВО получат более 40 единиц авиатехники" [Pilots of the Southern Military District will receive more than 40 aircraft]. vpk-news.ru (in Russian). 10 October 2014. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "Истребительная авиация ЮВО пополнилась модернизированными самолетами Су-27СМ3" [Fighter aviation of the Southern Military District replenished with modernized Su-27SM3 aircraft]. Center for Analysis of the World Arms Trade (in Russian). 30 October 2018. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ↑ "Истребительная авиация ЮВО пополнилась звеном новых модернизированных самолетов Су-27СМ3" [Fighter aviation of the Southern Military District was replenished with a flight of new modernized Su-27SM3 aircraft]. Center for Analysis of the World Arms Trade (in Russian). 19 November 2018. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ↑ "Истребительная авиация ЮВО пополнилась звеном новых модернизированных самолетов Су-27СМ3 поколения 4++" [Fighter aviation of the Southern Military District has been replenished with a flight of new modernized Su-27SM3 aircraft of the 4++ generation]. Center for Analysis of the World Arms Trade (in Russian). 29 December 2018. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ↑ "Су-27". Ukrainian military portal (in Ukrainian). 13 October 2009. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- 1 2 Hillebrand, Niels (11 October 2008). "Su-27 Flanker Operators List". Milavia. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- ↑ Gordon & Davison (2006), p. 101.

- ↑ Cenciotti, David (6 January 2017). "These crazy photos show a Russian Su-27 Flanker dogfighting with a U.S. Air Force F-16 inside Area 51". The Aviationist. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ↑ "Directory: World Air Forces". Flight International, 14–20 December 2010.

- ↑ "Су-27 сняты с вооружения в Белоруссии" [Su-27s disarmed in Belarus]. BPMD (in Russian). 15 December 2012. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012.

- ↑ "Belarus to modernize its fleet of Sukhoi Su-27 jet fighter". Air Recognition. 31 January 2014. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ↑ "Aircraft - Make / Model Inquiry". FAA Registry. Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ "Sukhoi SU-27 Flankers". Pride Aircraft. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ↑ Ward, Andrew (30 August 2010). "Cold war base to be private 'Top Gun' school". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Air International October 2010, p. 9.

- ↑ "NATO 'no comment' on Russian warplane deal report". RIA Novosti. 1 September 2010. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "Belarus to upgrade its Su-27 fighters". China Network Television. 1 February 2014. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Tsompanidis, Angelos (23 July 2007). "Su-27 crash Salgareda Airshow 1990". YouTube. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "9 September 1990 crash of Su-27". Aviation Safety Network. 11 January 2011. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012.

- ↑ Sidorov, Pavel. "Катастрофа "Русских Витязей"" [Catastrophe of "Russian Knights"]. Airbase.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2007.

- ↑ "Pilots blamed for air show crash". CNN. 7 August 2002. Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ↑ Wikinews contributors (23 October 2005). "Russian fighter crash in Lithuania: investigation concludes". Wikinews.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - 1 2 "Pilot dies as Russia jets collide". BBC News. 17 August 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ↑ Ranter, Harro. "Accident Sukhoi Su-27UB 63 Black, 30 August 2009". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017.

- ↑ Russian Jet Bumps Air Force Drone over Black Sea, Causing Unmanned Aircraft to Crash, Thomas Novelly and Travis Tritten, Military.com, 2023-04-14

- ↑ "Открытая площадка" [Open Area]. Central Museum of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (in Russian). Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ↑ "Sukhoi Su-27PD, s/n 27 red Russian AF, c/n 36911031003". Aerial Visuals Airframe Dossier. Archived from the original on 7 July 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- ↑ "Sukhoi Su-27". National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ D'Urso, Stefano (27 September 2023). "U.S. Air Force National Museum Acquires Former Ukrainian Su-27UB Flanker". The Aviationist. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ Gordon & Davison (2006), pp. 91–92, 95–96.

- 1 2 3 4 "Su-27SK: Aircraft Performance". Sukhoi. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ↑ "Sukhoi Su-27SKM single-seat multirole fighter". KnAAPO. Archived from the original on 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "Su-27". Deagel.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017.

- ↑ "Su-27 Flanker Front-Line Fighter Aircraft, Russia". Airforce-Technology.com. 16 July 2021. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017.

- ↑ "Su-27 Flanker, Sukhoi". Fighter-planes.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- 1 2 Newdick, Thomas (24 August 2023). "Ukraine's Su-27s Are Launching JDAM-ER Winged Bombs Too". The Drive. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ↑ "Sky searchers" (PDF). Jane's Defence Weekly. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2019.

- Bibliography

- "ECA Program Su-27 'Flankers' Destined for Iceland". Air International. Vol. 79, no. 4. October 2010. p. 9. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Gordon, Yefim (1999). Sukhoi Su-27 Flanker: Air Superiority Fighter. Airlife Publishing. ISBN 1-84037-029-7.

- Gordon, Yefim & Davison, Peter (2006). Sukhoi Su-27 Flanker. Warbird Tech. Vol. 42. North Branch, MN: Speciality Press. ISBN 978-1-58007-091-1.

- Ryabinkin, N. I. (1997). Sovremennye boevye samolyoty [Modern Combat Aircraft] (in Russian). Minsk: Elida. pp. 50–51. ISBN 985-6163-10-2.

- North, David M. (24 September 1990). "Su-27 Pilot Report (Part 1)" (PDF). Aviation Week. pp. 32–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2018.

- North, David M. (24 September 1990). "Su-27 Pilot Report (Part 2)" (PDF). Aviation Week. pp. 35–41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2018.

- Winchester, Jim (2012). Jet fighters : inside & out. New York: Rosen Pub. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-44885-982-5. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

External links

Media related to Sukhoi Su-27 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sukhoi Su-27 at Wikimedia Commons- Official Sukhoi Su-27SK webpage at Sukhoi and KnAAPO

- Official Sukhoi Su-27UBK webpage at Sukhoi

- Official Sukhoi Su-27SKM webpage at KnAAPO

- Zacharz, Michel (2005). "Sukhoi Su-27 "Flanker" / Sukhoi Su-27SKM". Zacharz.com.

- Kopp, Carlo (7 January 2007). "Sukhoi Flankers: The Shifting Balance of Regional Air Power". Air Power Australia: 1.

- Kopp, Carlo (August 2003). "Asia's Advanced Flankers" (PDF). Air Power Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2006.

- "Su-27UBs in the United States". Pride Aircraft. 2009. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009.