Shunga Empire | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 187 BCE–73 BCE | |||||||||

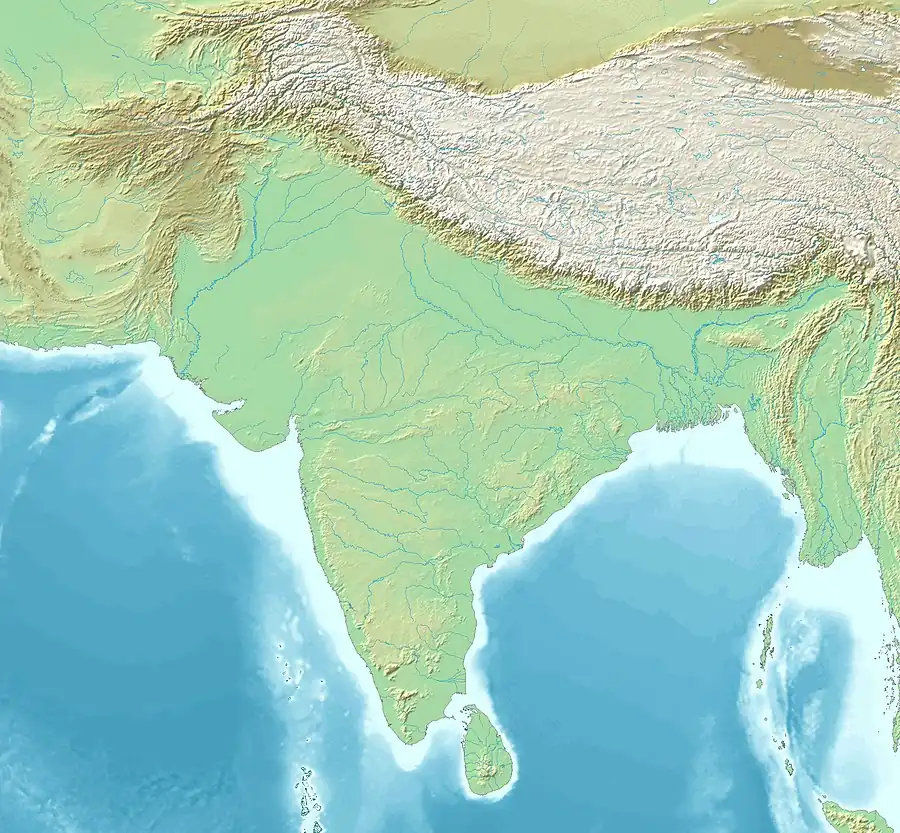

Territory of the Shungas c. 150 BCE.[1] | |||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

• c. 185 – c. 151 BCE | Pushyamitra (first) | ||||||||

• c. 151–141 BCE | Agnimitra | ||||||||

• c. 83–73 BCE | Devabhuti (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient India | ||||||||

• Assassination of Brihadratha by Pushyamitra Shunga | 187 BCE | ||||||||

• Assassination of Devabhuti by Vasudeva Kanva | 73 BCE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The Shunga dynasty (IAST: Śuṅga) was the seventh ruling dynasty of Magadha and controlled most of the northern Indian subcontinent from around 187 to 73 BCE. The dynasty was established by Pushyamitra, after taking the throne of Magadha from the Mauryas. The Shunga Empire's capital was Pataliputra, but later emperors such as Bhagabhadra also held court at Besnagar (modern Vidisha) in eastern Malwa.[2] This dynasty is also responsible for successfully fighting and resisting the Greeks in Shunga-Greek War.[3][4][5]

Pushyamitra ruled for 36 years and was succeeded by his son Agnimitra. There were ten Shunga rulers. However, after the death of Agnimitra, the second king of the dynasty, the empire rapidly disintegrated:[6] inscriptions and coins indicate that much of northern and central India consisted of small kingdoms and city-states that were independent of any Shunga hegemony.[7] The dynasty is noted for its numerous wars with both foreign and indigenous powers. They fought the Kalinga, the Satavahana dynasty, the Indo-Greek Kingdom and possibly the Panchalas and Mitras of Mathura.

Art, education, philosophy, and other forms of learning flowered during this period, including small terracotta images, larger stone sculptures, and architectural monuments such as the stupa at Bharhut, and the renowned Great Stupa at Sanchi. The Shunga rulers helped to establish the tradition of royal sponsorship of learning and art. The script used by the empire was a variant of Brahmi script and was used to write Sanskrit.

The Shungas were important patrons of culture at a time when some of the most important developments in Hindu thought were taking place. Patanjali's Mahābhāṣya was composed in this period. Artistry also progressed with the rise of the Mathura art style.

The last of the Shunga emperors was Devabhuti (83–73 BCE). He was assassinated by his minister Vasudeva Kanva and was said to have been overfond of the company of women. The Shunga dynasty was replaced by the Kanvas. The Kanva dynasty succeeded the Shungas around 73 BCE.

Name

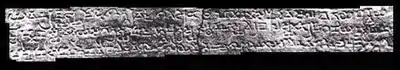

The name "Shunga" has only been used for convenience to designate the historical polity now generally described as "Shunga Empire", or the historical period known as the "Shunga period", which follows the fall of the Maurya Empire.[8] The term comes from a single epigraphic inscription in Bharhut, in which a dedication to the Buddhist Bharhut stupa is said to have been made "at the time of the Suga kings" (Suganam raje), with no indication as to whom these "Suga kings" might be.[8] Other broadly contemporary inscriptions, such as the Heliodorus pillar inscription, are only assumed to relate to Shunga rulers.[8] The Ayodhya Inscription of Dhana mentions a ruler named Pushyamitra, but does not mention the name "Shunga".

The Bharut epigraph appears on a pillar of the gateway of the stupa, and mentions its erection "during the rule of the Sugas, by Vatsiputra Dhanabhuti".[9][10] The expression used (Suganam raje, Brahmi script: 𑀲𑀼𑀕𑀦𑀁 𑀭𑀚𑁂), may mean "during the rule of the Shungas", although not without ambiguity as it could also be "during the rule of the Sughanas", a northern Buddhist kingdom.[11][10] There is no other instance of the name "Shunga" in the epigraphical record of India.[12] The unique inscription reads:

1. Suganam raje raño Gāgīputasa Visadevasa

2. pautena, Gotiputasa Āgarajusa putena

3. Vāchhīputena Dhanabhūtina kāritam toranām

4. silākammamto cha upamno.During the reign of the Sugas (Sughanas, or Shungas) the gateway was caused to be made and the stone-work presented by Dhanabhūti, the son of Vāchhī, son of Agaraju, the son of a Goti and grandson of king Visadeva, the son of Gāgī.

Dhanabhuti was making a major dedication to a Buddhist monument, Bharhut, whereas the historical "Shungas" are known to have been Hindu monarchs, which would suggest that Dhanabhuti himself may not have been a member of the Shunga dynasty.[15] Neither is he known from "Shunga" regnal lists.[15][16] The mention "in the reign of the Shungas" also suggests that he was not himself a Shunga ruler, only that he may have been a tributary of the Shungas, or a ruler in a neighbouring territory, such as Kosala or Panchala.[16][15]

The name "Sunga" or "Shunga" is also used in the Vishnu Purana, the date of which is contested, to designate the dynasty of kings starting with Pushyamitra c. 185 BCE, and ending with Devabhuti circa 75 BCE. According to the Vishnu Purana:[8][17][18]

Ten Maurya kings will reign for one hundred and thirty-seven years. After them the Śuṅgas will rule the earth. The general Puṣpamitra will kill his sovereign and usurp the kingdom. His son will be Agnimitra. His son will be Sujyeṣṭha. His son will be Vasumitra. His son will be Ārdraka. His son will be Pulindaka. His son will be Ghoṣavasu. His son will be Vajramitra. His son will be Bhāgavata. His son will be Devabhūti. These ten Śuṅgas will rule the earth for one hundred and twelve years.

— Vishnu Purana, Book Four: The Royal Dynasties.[19]

Origins

According to historical reconstructions, the Shunga dynasty was established in 184 BCE, about 50 years after Ashoka's death, when the emperor Brihadratha Maurya, the last ruler of the Maurya Empire, was assassinated by his Senānī or commander-in-chief, Pushyamitra,[20] while he was reviewing the Guard of Honour of his forces. Pushyamitra then ascended the throne.[21][22]

Pushyamitra became the ruler of Magadha and neighbouring territories. His realm essentially covered the central parts of the old Mauryan Empire.[23] The Shunga definitely had control of the central city of Ayodhya in northern central India, as is proved by the Dhanadeva-Ayodhya inscription.[23] However, the city of Mathura further west never seems to have been under the direct control of the Shungas, as no archaeological evidence of a Shunga presence has ever been found in Mathura.[24] On the contrary, according to the Yavanarajya inscription, Mathura was probably under the control of Indo-Greeks from some time between 180 BCE and 100 BCE, and remained so as late as 70 BCE.[24]

Some ancient sources however claim a greater extent for the Shunga Empire: the Asokavadana account of the Divyavadana claims that the Shungas sent an army to persecute Buddhist monks as far as Sakala (Sialkot) in the Punjab region in the northwest:

... Pushyamitra equipped a fourfold army, and intending to destroy the Buddhist religion, he went to the Kukkutarama (in Pataliputra). ... Pushyamitra therefore destroyed the sangharama, killed the monks there, and departed. ... After some time, he arrived in Sakala, and proclaimed that he would give a ... reward to whoever brought him the head of a Buddhist monk.[25]: 293

Also, the Malavikagnimitra claims that the empire of Pushyamitra extended to the Narmada River in the south. They may also have controlled the city of Ujjain.[23] Meanwhile, Kabul and much of the Punjab passed into the hands of the Indo-Greeks and the Deccan Plateau to the Satavahana dynasty.

Pushyamitra died after ruling for 36 years (187–151 BCE). He was succeeded by son Agnimitra. This prince is the hero of a famous drama by one of India's greatest playwrights, Kālidāsa. Agnimitra was viceroy of Vidisha when the story takes place.

The power of the Shungas gradually weakened. It is said that there were ten Shunga emperors. The Shungas were succeeded by the Kanva dynasty around 73 BCE.

Buddhism

Accounts of persecution

Following the Mauryans, the first Sunga emperor, a Brahmin named Pushyamitra,[26] is believed by some historians to have persecuted Buddhists and contributed to a resurgence of Brahmanism that forced Buddhism outwards to Kashmir, Gandhara and Bactria.[27] Buddhist scripture such as the Asokavadana account of the Divyavadana and ancient Tibetan historian Taranatha have written about persecution of Buddhists. Pushyamitra is said to have burned down Buddhist monasteries, destroyed stupas, massacred Buddhist monks and put rewards on their heads, but some consider these stories as probable exaggerations.[27][28]

"... Pushyamitra equipped a fourfold army, and intending to destroy the Buddhist religion, he went to the Kukkutarama. ... Pushyamitra therefore destroyed the sangharama, killed the monks there, and departed. ... After some time, he arrived in Sakala, and proclaimed that he would give a ... reward to whoever brought him the head of a Buddhist monk."

Pushyamitra is known to have revived the supremacy of the Bramahnical religion and reestablished animal sacrifices (Yajnas) that had been prohibited by Ashoka.[28]

Accounts against persecution

Later Shunga emperors were seen as amenable to Buddhism and as having contributed to the building of the stupa at Bharhut.[30] During his reign the Buddhist monuments of Bharhut and Sanchi were renovated and further improved. There is enough evidence to show that Pushyamitra patronised buddhist art.[31] However, given the rather decentralised and fragmentary nature of the Shunga state, with many cities actually issuing their own coinage, as well as the relative dislike of the Shungas for the Buddhist religion, some authors argue that the constructions of that period in Sanchi for example cannot really be called "Shunga". They were not the result of royal sponsorship, in contrast with what happened during the Mauryas, and most of the dedications at Sanchi were private or collective, rather than the result of royal patronage.[32]

Some writers believe that Brahmanism competed in political and spiritual realm with Buddhism[27] in the Gangetic plains. Buddhism flourished in the realms of the Bactrian kings.

Some Indian scholars are of the opinion that the orthodox Shunga emperors were not intolerant towards Buddhism and that Buddhism prospered during the time of the Shunga emperors. The existence of Buddhism in Bengal in the Shunga period can also be inferred from a terracotta tablet that was found at Tamralipti and is on exhibit at the Asutosh Museum in Kolkata.

Royal dedications

Two dedication by a king Brahmamitra and a king Indragnimitra are recorded at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, and have been claimed to show Sunga support for Buddhism. These kings however are essentially unknown, and do not form a part of the Shunga recorded genealogy, but they are thought to be post-Ashokan and to belong to the period of Sunga rule.[33][34] A Brahmamitra is known otherwise as a local ruler of Mathura, but Indragnimitra is unknown, and according to some authors, Indragnimitra is in fact not even mentioned as a king in the actual inscription.[34][35]

- An inscription at Bodh Gaya at the Mahabodhi Temple records the construction of the temple as follows:

- "The gift of Nagadevi the wife of King Brahmamitra."

- Another inscription reads:

- "The gift of Kurangi, the mother of living sons and the wife of King Indragnimitra, son of Kosiki. The gift also of Srima of the royal palace shrine.[36][37] "

Cunningham has regretted the loss of the latter part of these important records. As regards the first coping inscription, he has found traces of eleven Brahmi letters after "Kuramgiye danam", the first nine of which read "rajapasada-cetika sa". Bloch reads these nine letters as "raja-pasada-cetikasa" and translates this expression in relation to the preceding words:

"(the gift of Kurangi, the wife of Indragnimitra and the mother of living sons), "to the caitya (cetika) of the noble temple", taking the word raja before pasada as an epithet on ornans, distinguishing the temple as a particularly large and stately building similar to such expressions as rajahastin 'a noble elephant', rajahamsa `a goose (as distinguished from hamsa 'a duck'), etc."

Cunningham has translated the expression by "the royal palace, the caitya", suggesting that "the mention of the raja-pasada would seem to connect the donor with the king's family." Luders doubtfully suggests "to the king's temple" as a rendering of "raja-pasada-cetikasa."

Shunga period contributions in Sanchi

On the basis of Ashokavadana, it is presumed that the stupa may have been vandalised at one point sometime in the 2nd century BCE, an event some have related to the rise of the Shunga emperor Pushyamitra who overtook the Mauryan Empire as an army general. It has been suggested that Pushyamitra may have destroyed the original stupa, and his son Agnimitra rebuilt it.[38] The original brick stupa was covered with stone during the Shunga period.

According to historian Julia Shaw, the post-Mauryan constructions at Sanchi cannot be described as "Sunga" as sponsorship for the construction of the stupas, as attested by the numerous donative inscriptions, was not royal but collective, and the Sungas were known for their opposition to Buddhism.[39]

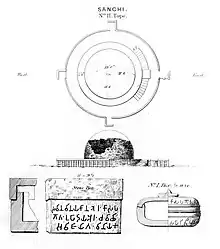

Great Stupa (No 1)

During the later rule of the Shunga, the stupa was expanded with stone slabs to almost twice its original size. The dome was flattened near the top and crowned by three superimposed parasols within a square railing. With its many tiers it was a symbol of the dharma, the Wheel of the Law. The dome was set on a high circular drum meant for circumambulation, which could be accessed via a double staircase. A second stone pathway at ground level was enclosed by a stone balustrade. The railing around Stupa 1 do not have artistic reliefs. These are only slabs, with some dedicatory inscriptions. These elements are dated to c. 150 BCE.[40]

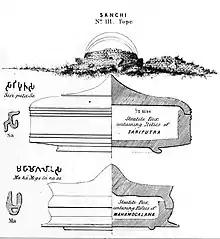

Stupa No2 and Stupa No3

The buildings which seem to have been commissioned during the rule of the Shungas are the Second and Third stupas (but not the highly decorated gateways, which are from the following Satavahana period, as known from inscriptions), and the ground balustrade and stone casing of the Great Stupa (Stupa No 1). The Relics of Sariputra and Mahamoggallana are said to have been placed in Stupa No 3.[41] These are dated to c. 115 BCE for the medallions, 80 BCE for the gateway carvings,[42] slightly after the reliefs of Bharhut, with some reworks down to the 1st century CE.[40][42]

The style of the Shunga period decorations at Sanchi bear a close similarity to those of Bharhut, as well as the peripheral balustrades at Bodh Gaya, which are thought to be the oldest of the three.

| Shunga structures and decorations (150-80 BCE) | |

Great Stupa (Stupa expansion and balustrades only are Shunga). Undecorated ground railings dated to approximately 150 BCE.[40] |

|

.JPG.webp) Stupa No 2 Entirely Shunga work. The reliefs are thought to date to the last quarter of the 2nd century BCE (c. 115 BCE for the medallions, 80 BCE for the gateway carvings),[42] slightly after the reliefs of Bharhut, with some reworks down to the 1st century CE.[40][42] |

|

Stupa No 3 (Stupa and balustrades only are Shunga). |

|

Wars of the Shungas

War and conflict characterised the Shunga period. They are known to have warred with the Kalingas, Satavahanas, the Indo-Greeks, and possibly the Panchalas and Mathuras.

The Shunga Empire's wars with the Indo-Greek Kingdom figure greatly in the history of this period. From around 180 BCE the Greco-Bactrian ruler Demetrius conquered the Kabul Valley and is theorised to have advanced into the trans-Indus to confront the Shungas.[28] The Indo-Greek Menander I is credited with either joining or leading a campaign to Pataliputra with other Indian rulers; however, very little is known about the exact nature and success of the campaign. The net result of these wars remains uncertain.

Literary evidence

Several works, such as the Mahabharata and the Yuga Purana describe the conflict between the Shungas and the Indo-Greeks.

Military expeditions of the Shungas

Scriptures such as the Ashokavadana claim that Pushyamitra toppled Emperor Brihadratha and killed many Buddhist monks.[49] Then it describes how Pushyamitra sent an army to Pataliputra and as far as Sakala (Sialkot), in the Punjab, to persecute Buddhist monks.[50]

War with the Yavanas (Greeks)

The Indo-Greeks, called Yavanas in Indian sources, either led by Demetrius I or Menander I, then invaded India, possibly receiving the help of Buddhists.[51] Menander in particular is described as a convert to Buddhism in the Milindapanha.

The Hindu text of the Yuga Purana, which describes Indian historical events in the form of a prophecy,[52][note 1] relates the attack of the Indo-Greeks on the Shunga capital Pataliputra, a magnificent fortified city with 570 towers and 64 gates according to Megasthenes,[54] and describes the impending war for city:

Then, after having approached Saketa together with the Panchalas and the Mathuras, the Yavanas, valiant in battle, will reach Kusumadhvaja "the town of the flower-standard", Pataliputra. Then, once Puspapura (another name of Pataliputra) has been reached and its celebrated mud-walls cast down, all the realm will be in disorder

— Yuga Purana, Paragraph 47–48, 2002 edition)

However, the Yuga Purana indicates that the Yavanas (Indo-Greeks) did not remain for long in Pataliputra, as they were faced with a civil war in Bactria.

Western sources also suggest that this new offensive of the Greeks into India led them as far as the capital Pataliputra:[55]

Those who came after Alexander went to the Ganges and Pataliputra

— Strabo, 15.698

Battle on the Sindhu river

An account of a direct battle between the Greeks and the Shunga is also found in the Mālavikāgnimitram, a play by Kālidāsa which describes a battle between a squadron of Greek cavalrymen and Vasumitra, the grandson of Pushyamitra, accompanied by a hundred soldiers on the "Sindhu river", in which the Indians defeated a squadron of Greeks and Pushyamitra successfully completed the Ashvamedha Yagna.[56] This river may be the Indus river in the northwest, but such expansion by the Shungas is unlikely, and it is more probable that the river mentioned in the text is the Sindh River or the Kali Sindh River in the Ganges Basin.[57]

Epigraphic and archaeological evidence

Dhanadeva-Ayodhya inscription

Ultimately, Shunga rule seems to have extended to the area of Ayodhya. Shunga inscriptions are known as far as Ayodhya in northern central India;[23] in particular, the Dhanadeva-Ayodhya inscription refers to a local king Dhanadeva, who claimed to be the sixth descendant of Pushyamitra. The inscription also records that Pushyamitra performed two Ashvamedhas (victory sacrifices) in Ayodhya.[58]

Yavanarajya inscription

The Greeks seem to have maintained control of Mathura. The Yavanarajya inscription, also called the "Maghera inscription", discovered in Mathura, suggests that the Indo-Greeks were in control of Mathura during the 1st century BCE.[59][60] The inscription is important in that it mentions the date of its dedication as "The last day of year 116 of Yavana hegemony (Yavanarajya)". It is considered that this inscription is attesting the control of the Indo-Greeks in the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE in Mathura, a fact that is also confirmed by numismatic and literary evidence.[24] Moreover, it does not seem that the Shungas ever ruled in Mathura or Surasena since no Shunga coins or inscriptions have been found there.[24]

The Anushasana Parva of the Mahabharata affirms that the city of Mathura was under the joint control of the Yavanas and the Kambojas.[61]

Later however, it seems the city of Mathura was retaken from them, if not by the Shungas themselves, then probably by other indigenous rulers such as the Datta dynasty or the Mitra dynasty, or more probably by the Indo-Scythian Northern Satraps under Rajuvula. In the region of Mathura, the Arjunayanas and Yaudheyas mention military victories on their coins ("Victory of the Arjunayanas", "Victory of the Yaudheyas"), and during the 1st century BCE, the Trigartas, Audumbaras and finally the Kunindas also started to mint their own coins, thus affirming independence from the Indo-Greeks, although the style of their coins was often derived from that of the Indo-Greeks.

Heliodorus pillar

Very little can be said with great certainty. However, what does appear clear is that the two realms appeared to have established normalised diplomatic relations in the succeeding reigns of their respective rulers. The Indo-Greeks and the Shungas seem to have reconciled and exchanged diplomatic missions around 110 BCE, as indicated by the Heliodorus pillar, which records the dispatch of a Greek ambassador named Heliodorus, from the court of the Indo-Greek king Antialcidas, to the court of the Shunga emperor Bhagabhadra at the site of Vidisha in central India.

Decline

After the death of Agnimitra, the second king of the dynasty, the empire rapidly disintegrated:[6] inscriptions and coins indicate that much of northern and central India consisted of small kingdoms and city-states that were independent of any Shunga hegemony.[7]

The last king of Sungas, Devabhuti was assassinated by his minister Vasudeva Kanva, who then established Kanva dynasty.[21] According to the Puranas: "The Andhra Simuka will assail the Kanvayanas and Susarman, and destroy the remains of the Sungas' power and will obtain this earth."[62] The Andhras did indeed destroy the last remains of the Sunga state in central India somewhere around Vidisha,[63] probably as a feeble rump state.

Art

The Shunga art style differed somewhat from imperial Mauryan art, which was influenced by Persian art. In both, continuing elements of folk art and cults of the Mother goddess appear in popular art, but are now produced with more skill in more monumental forms. The Shunga style was thus seen as 'more Indian' and is often described as the more indigenous.[64]

Art, education, philosophy, and other learning flowered during this period. Most notably, Patanjali's Yoga Sutras and Mahabhashya were composed in this period. It is also noted for its subsequent mention in the Malavikaagnimitra. This work was composed by Kalidasa in the later Gupta period, and romanticised the love of Malavika and King Agnimitra, with a background of court intrigue.

Artistry on the subcontinent also progressed with the rise of the Mathura school, which is considered the indigenous counterpart to the more Hellenistic Gandhara school (Greco-Buddhist art) of Afghanistan and North-Western frontier of India (modern day Pakistan).

During the historical Shunga period (185 to 73 BCE), Buddhist activity also managed to survive somewhat in central India (Madhya Pradesh) as suggested by some architectural expansions that were done at the stupas of Sanchi and Bharhut, originally started under Emperor Ashoka. It remains uncertain whether these works were due to the weakness of the control of the Shungas in these areas, or a sign of tolerance on their part.

| Shunga statuettes and reliefs |

|

Script

The script used by the Shunga was a variant of Brahmi, and was used to write the Sanskrit language. The script is thought to be an intermediary between the Maurya and the Kalinga Brahmi scripts.[65]

| Shunga coinage |

|

| History of South Asia |

|---|

_without_national_boundaries.svg.png.webp) |

List of Shunga Emperors

| Emperor | Reign |

|---|---|

| Pushyamitra | 185–149 BCE |

| Agnimitra | 149–141 BCE |

| Vasujyeshtha | 141–131 BCE |

| Vasumitra | 131–124 BCE |

| Bhadraka | 124–122 BCE |

| Pulindaka | 122–119 BCE |

| Ghosha or Vajramitra | 119-114 BCE |

| Bhagabhadra | 114-83 BCE |

| Devabhuti | 83–73 BCE |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Formerly, scholars doubted the validity of the Yuga Purana, because manuscripts of it have been highly corrupted over its history; however, Sanskrit scholar Ludo Rocher says that recent "research has [...] been concerned with establishing a more acceptable text," and "The Yuga [Purana] is important primarily as a historical document. It is a matter-of-fact chronicle [...] of the Magadha empire, down to the breakdown of the Sungas and the arrival of the Sakas. It is unique in its description of the invasion and retirement of the Yavanas in Magadha."[53]

References

Citations

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 145, map XIV.1 (c). ISBN 0226742210.

- ↑ Stadtner, Donald (1975). "A Śuṅga Capital from Vidiśā". Artibus Asiae. 37 (1/2): 101–104. doi:10.2307/3250214. JSTOR 3250214.

- ↑ Mani, Chandra Mauli (2005). A Journey Through India's Past. Northern Book Centre. p. 38. ISBN 978-81-7211-194-6.

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 170. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, Hem Channdra (1923). Political history of ancient India, from the accession of Parikshit to the extinction of the Gupta dynasty. Robarts - University of Toronto. Calcutta, Univ. of Calcutta. p. 205.

- 1 2 K.A. Nilkantha Shastri (1970), A Comprehensive History of India: Volume 2, p.108: "Soon after Agnimitra there was no 'Sunga empire'."

- 1 2 Bhandare, Shailendra. "Numismatics and History: The Maurya-Gupta Interlude in the Gangetic Plain". in Between the Empires: Society in India, 300 to 400, ed. Patrick Olivelle (2006), p.96

- 1 2 3 4 Salomon, Richard (10 December 1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- ↑ "Bharhut Gallery". INC-ICOM Galleries. Indian National Committee of the International Council of Museums. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- 1 2 Kumar, Ajit (2014). "Bharhut Sculptures and their untenable Sunga Association". Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology. 2: 230.

- ↑ Olivelle, Patrick (13 July 2006). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1.

- ↑ Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- ↑ Luders, H. (1963). CORPUS INSCRIPTIONS INDICARUM VOL II PART II. India Archaeological Society. p. 11.

- ↑ The Stupa of Bharhut, Alexander Cunningham, p.128

- 1 2 3 Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9789004155374.

- 1 2 Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 13. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ↑ A Comprehensive History Of Ancient India (3 Vol. Set). Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. 1 December 2003. p. 93. ISBN 978-81-207-2503-4.

- ↑ Indian History. Allied Publishers. p. 254. ISBN 978-81-8424-568-4.

- ↑ Taylor, McComas (2021). "The Royal Dynasties". The Visnu Purana. ANU Press: 330. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1sjwpmj.10. JSTOR j.ctv1sjwpmj.10. S2CID 244448788.

- ↑ "Pushyamitra is said in the Puranas to have been the senānī or army-commander of the last Maurya emperor Brihadratha" The Yuga Purana, Mitchener, 2002.

- 1 2 Thapar 2013, p. 296.

- ↑ Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE By Patrick Olivelle, Oxford University Press, Page 147-152

- 1 2 3 4 Ancient Indian History and Civilization, Sailendra Nath Sen, New Age International, 1999, p.169

- 1 2 3 4 History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE, Sonya Rhie Quintanilla, BRILL, 2007, p.8-10

- ↑ John S. Strong (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ Mishra, Ram Kumar (2012). "Pushyamitra Sunga and the Buddhists". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 73: 50–57. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44156189.

Pushyamitra Sunga, himself a Brahmana,...

- 1 2 3 Sarvastivada pg 38–39

- 1 2 3 A Journey Through India's Past Chandra Mauli Mani, Northern Book Centre, 2005, p.38

- ↑ John S. Strong (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ Akira Hirakawa, Paul Groner, "A History of Indian Buddhism: From Sakyamuni to Early Mahayana", Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1996, ISBN 81-208-0955-6 pg 223

- ↑ Sir john Marshall, "A Guide to Sanchi", 1918

- ↑ Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, c. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD Julia Shaw, Routledge, 2016 p.58

- ↑ Asoka, Mookerji Radhakumud, Motilal Banarsidass Publishe, 1962 p.152

- 1 2 Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE Patrick Olivelle, Oxford University Press, 2006 p.58-59

- ↑ Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE Patrick Olivelle, Oxford University Press, 2006 p.75

- ↑ (Barua, B.M., 'Old Buddhist Shrines at Bodh-Gaya Inscriptions)

- ↑ "Bodh Gaya from 500 BCE to 500 CE". buddhanet.net.

- ↑ "Who was responsible for the wanton destruction of the original brick stupa of Ashoka and when precisely the great work of reconstruction was carried out is not known, but it seems probable that the author of the former was Pushyamitra, the first of the Shunga kings (184-148 BC), who was notorious for his hostility to Buddhism, and that the restoration was affected by Agnimitra or his immediate successor." in John Marshall, A Guide to Sanchi, p. 38. Calcutta: Superintendent, Government Printing (1918).

- ↑ Shaw, Julia (12 August 2016). Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, c. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD. Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-315-43263-2.

It is inaccurate to refer to the post-Mauryan monuments at Sanchi as Sunga. Not only was Pusyamitra reputedly animical to Buddhism, but most of the donative inscriptions during this period attest to predominantly collective and nonroyal modes of sponsorship.

- 1 2 3 4 Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, C. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD, Julia Shaw, Left Coast Press, 2013 p.88ff

- ↑ Marshall p.81

- 1 2 3 4 5 Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, C. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD, Julia Shaw, Left Coast Press, 2013 p.90

- ↑ Marshall p.82

- ↑ Coatsworth, John; Cole, Juan; Hanagan, Michael P.; Perdue, Peter C.; Tilly, Charles; Tilly, Louise (16 March 2015). Global Connections: Volume 1, To 1500: Politics, Exchange, and Social Life in World History. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-316-29777-3.

- ↑ Atlas of World History. Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0.

- ↑ Fauve, Jeroen (2021). The European Handbook of Central Asian Studies. Ibidem Press. p. 403. ISBN 978-3-8382-1518-1.

- ↑ Török, Tibor (July 2023). "Integrating Linguistic, Archaeological and Genetic Perspectives Unfold the Origin of Ugrians". Genes. 14 (7): Figure 1. doi:10.3390/genes14071345. ISSN 2073-4425. PMC 10379071. PMID 37510249.

- ↑ D.N. Jha,"Early India: A Concise History"p.150, plate 17

- ↑ John S. Strong (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ "Pushyamitra equipped a fourfold army, and intending to destroy the Buddhist religion, he went to the Kukkutarama (in Pataliputra). ... Pushyamitra therefore destroyed the sangharama, killed the monks there, and departed. ... After some time, he arrived in Sakala, and proclaimed that he would give a ... reward to whoever brought him the head of a Buddhist monk."John S. Strong (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ A Journey Through India's Past Chandra Mauli Mani, Northern Book Centre, 2005, p.39

- ↑ "For any scholar engaged in the study of the presence of the Indo-Greeks or Indo-Scythians before the Christian Era, the Yuga Purana is an important source material" Dilip Coomer Ghose, General Secretary, The Asiatic Society, Kolkata, 2002

- ↑ Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Purāṇas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 253–254. ISBN 9783447025225.

- ↑ "Megasthenes: Indika". Project South Asia. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008.

The greatest city in India is that which is called Palimbothra, in the dominions of the Prasians [...] Megasthenes informs us that this city stretched in the inhabited quarters to an extreme length on each side of eighty stadia, and that its breadth was fifteen stadia, and that a ditch encompassed it all round, which was six hundred feet in breadth and thirty cubits in depth, and that the wall was crowned with 570 towers and had four-and-sixty gates. (Arr. Ind. 10. 'Of Pataliputra and the Manners of the Indians')

- ↑ Indian History Allied Publishers

- ↑ The Malavikágnimitra : a Sanskrit play by Kālidāsa; Tawney, C. H. p.91

- ↑ "Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian institution", Bopearachchi, p16. Also: "Kalidasa recounts in his Mālavikāgnimitra (5.15.14–24) that Puṣpamitra appointed his grandson Vasumitra to guard his sacrificial horse, which wandered on the right bank of the Sindhu river and was seized by Yavana cavalrymen- the latter being thereafter defeated by Vasumitra. The "Sindhu" referred to in this context may refer the river Indus: but such an extension of Shunga power seems unlikely, and it is more probable that it denotes one of two rivers in central India -either the Sindhu river which is a tributary of the Yamuna, or the Kali-Sindhu river which is a tributary of the Chambal." The Yuga Purana, Mitchener, 2002.

- ↑ Bakker, Hans (1982). "The rise of Ayodhya as a place of pilgrimage". Indo-Iranian Journal. 24 (2): 103–126. doi:10.1163/000000082790081267. S2CID 161957449.

- ↑ Sonya Rhie Quintanilla (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 254. ISBN 978-90-04-15537-4.

- ↑ Shankar Goyal, ed. (2004). India's ancient past. Jaipur: Book Enclave. p. 189. ISBN 9788181520012.

Some Newly Discovered Inscriptions from Mathura : The Meghera Well Stone Inscription of Yavanarajya Year 160 Recently a stone inscription was acquired in the Government Museum, Mathura.

- ↑ "tatha Yavana Kamboja Mathuram.abhitash cha ye./ ete ashava.yuddha.kushaladasinatyasi charminah."//5 — (MBH 12/105/5, Kumbhakonam Ed)

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, Hem Channdra (1923). Political history of ancient India, from the accession of Parikshit to the extinction of the Gupta dynasty. Calcutta, Univ. of Calcutta. p. 216.

- ↑ Sen, Sailendra Nath (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International, 1999. p. 170. ISBN 978-8-12241-198-0.

- ↑ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415329200.

- ↑ "Silabario Sunga". proel.org.

Sources

- Thapar, Romila (2013), The Past Before Us, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72651-2

- "The Legend of King Ashoka, A study and translation of the Ashokavadana", John Strong, Princeton Library of Asian translations, 1983, ISBN 0-691-01459-0

- "Dictionary of Buddhism" by Damien KEOWN (Oxford University Press, 2003) ISBN 0-19-860560-9

- Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas, Romila Thapar, 1961 (revision 1998); Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-564445-X

- "The Yuga Purana", John E. Mitchiner, Kolkata, The Asiatic Society, 2002, ISBN 81-7236-124-6

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)