| Swan River Nyungar: Derbarl Yerrigan | |

|---|---|

| |

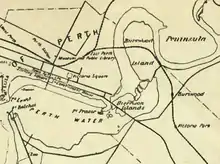

Map of the area around Perth, showing the location of the Swan River | |

| Location | |

| Country | Australia |

| State | Western Australia |

| City | Perth; Fremantle |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source confluence | Avon River with Wooroloo Brook |

| • location | below Mount Mambup |

| • coordinates | 31°44′34″S 116°4′3″E / 31.74278°S 116.06750°E |

| • elevation | 53 m (174 ft) |

| Mouth | Indian Ocean |

• location | Fremantle |

• coordinates | 32°4′25″S 115°42′52″E / 32.07361°S 115.71444°E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 72 km (45 mi) |

| Basin size | 121,000 km2 (47,000 sq mi) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Susannah Brook, Jane Brook |

| • right | Ellen Brook, Helena River, Bennett Brook, Canning River |

| [1]: 3 | |

The Swan River (Nyungar: Derbarl Yerrigan[2][3]) is a major river in the southwest of Western Australia. The river runs through the metropolitan area of Perth, Western Australia's capital and largest city.

Course of river

The Swan River estuary flows through the city of Perth. Its lower reaches are relatively wide and deep, with few constrictions, while the upper reaches are usually quite narrow and shallow.

The Swan River drains the Avon and coastal plain catchments, which have a total area of about 121,000 square kilometres (47,000 sq mi). It has three major tributaries, the Avon River, Canning River and Helena River. The latter two have dams (Canning Dam and Mundaring Weir) which provide a sizeable part of the potable water requirements for Perth and the surrounding regions. The Avon River contributes the majority of the freshwater flow. The climate of the catchment is Mediterranean, with mild wet winters, hot dry summers, and the associated highly seasonal rainfall and flow regime.

The Avon rises near Yealering, 221 kilometres (137 mi) southeast of Perth: it meanders north-northwest to Toodyay about 90 kilometres (56 mi) northeast of Perth, then turns southwest in Walyunga National Park – at the confluence of the Wooroloo Brook, it becomes the Swan River.

The Canning River rises from North Bannister, 100 kilometres (62 mi) southeast of Perth and joins the Swan at Applecross, opening into Melville Water. The river then narrows into Blackwall Reach, a narrow and deep stretch leading the river through Fremantle Harbour to the sea.

The estuary is subject to a microtidal regime, with a maximum tidal amplitude of about 1 metre (3 ft 3 in), although water levels are also subject to barometric pressure fluctuations.

Geology

Before the Tertiary, when the sea level was much lower than at present, the Swan River curved around to the north of Rottnest Island, and disgorged itself into the Indian Ocean slightly to the north and west of Rottnest. In doing so, it carved a gorge about the size of the Grand Canyon. Now known as Perth Canyon, this feature still exists as a submarine canyon near the edge of the continental shelf.

Geography

The Swan River drains the Swan Coastal Plain, a total catchment area of over 100,000 square kilometres (39,000 sq mi) in area. The river is located in a Mediterranean climate, with hot dry summers and cool wet winters, although this balance appears to be changing due to climate change. The Swan is located on the edge of the Darling Scarp, flowing downhill across the coastal plain to its mouth at Fremantle.

Sources

The Swan begins as the Avon River, rising near Yealering in the Darling Range, approximately 175 kilometres (109 mi) from its mouth at Fremantle. The Avon flows north, passing through the towns of Brookton, Beverley, York, Northam and Toodyay. It is joined by tributaries including the Dale River, the Mortlock River and the Brockman River. The Avon becomes the Swan as Wooroloo Brook enters the river near Walyunga National Park.

Tributaries

More tributaries including Ellen Brook, Jane Brook, Henley Brook, Wandoo Creek, Bennett Brook, Blackadder Creek, Limestone Creek, Susannah Brook, and the Helena River enter the river between Wooroloo Brook and Guildford; however, most of these have either dried up or become seasonally flowing due to human impacts such as land clearing and development.

Swan coastal plain

Between Perth and Guildford the river goes through several loops. Originally, areas including the Maylands Peninsula, Ascot and Burswood, through Claise Brook and north of the city to Herdsman Lake were swampy wetlands. Most of the wetlands have since been reclaimed for land development. Heirisson Island, upon which The Causeway passes over, was once a collection of small islets known as the Heirisson Islands.[4][5]

Perth Water and Melville Water

Perth Water, between the city and South Perth, is separated from the main estuary by the Narrows, over which the Narrows Bridge was built in 1959. The river then opens up into the large expanse of the river known as Melville Water. The Canning River enters the river at Canning Bridge in Applecross from its source 50 kilometres (31 mi) south-east of Armadale. The river is at its widest here, measuring more than 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) from north to south. Point Walter has a protruding spit that extends up to 800 metres (2,600 ft) into the river, forcing river traffic to detour around it.

Narrowing and Fremantle

The river narrows between Chidley Point and Blackwall Reach, curving around Point Roe and Preston Point before narrowing into the harbour. Stirling Bridge and the Fremantle Traffic Bridge cross the river north of the rivermouth. The Swan River empties into the Indian Ocean at Fremantle Harbour.

Notable features

- Fremantle Harbour

- Point Brown

- Rous Head

- Arthur Head

- Victoria Quay

- Point Direction

- Preston Point

- Rocky Bay

- Point Roe

- Chidley Point

- Blackwall Reach

- Butler's Hump

- Point Walter

- Mosman Bay

- Keanes Point

- Freshwater Bay

- Point Resolution

- Melville Water

- Lucky Bay

- Point Waylen

- Alfred Cove

- Point Dundas

- Waylen Bay

- Point Heathcote

- Quarry Point

- Mounts Bay

- Point Lewis

- Mill Point

- Point Belches

- Elizabeth Quay

- Pelican Point

- Matilda Bay

- The Narrows

- Perth Water

- Point Fraser

- Heirisson Island

- Claise Brook

- Maylands Peninsula

- Ron Courtney Island

- Swan Valley

- Kuljak Island

Flora and fauna

Plant and animal life found in or near the Swan-Canning Estuary include:

- Over 130 species of fish[6] including bull sharks[lower-alpha 1][7] (Carcharhinus leucas), rays, cobblers (Cnidoglanis macrocephalus, also known as Swan River catfish), herring (Elops machnata), pilchard (Sardinops neopilchardus), bream (Kyphosus sydneyanus), flatheads, leatherjackets and blowfish (Tetraodontidae)

- Jellyfish including Phyllorhiza punctata and Aurelia aurita

- Bottlenose dolphins

- Crustaceans including prawns and blue manna crabs

- Amphipod Melita zeylanica kauerti described based on specimen that was collected from under Middle Swan Bridge[8]

- Molluscs including Mytilidae, Galeommatidae

- Birds including the eponymous black swan, silver gull, cormorants (locally referred to as "shags"), twenty-eight parrots, rainbow lorikeet, kingfisher, red-tailed black cockatoo, Australian pelican, Australian magpie, heron and ducks

History

The river was named Swarte Swaene-Revier[9] by Dutch explorer, Willem de Vlamingh in 1697, after the famous black swans of the area. Vlamingh sailed with a small party up the river to around Heirisson Island.[10]

A French expedition under Nicholas Baudin also sailed up the river in 1801.

Governor Stirling's intention was that the name "Swan River" refer only to the watercourse upstream of the Heirisson Islands.[9] All of the rest, including Perth Water, he considered estuarine and which he referred to as "Melville Water". The Government notice dated 27 July 1829 stated "... the first stone will be laid of a new town to be called 'Perth', near the entrance to the estuary of the Swan River."

Almost immediately after the Town of Perth was established, a systematic effort was underway to reshape the river. This was done for many reasons:

- to alleviate flooding in winter periods;

- improve access for boats by having deeper channels and jetties;

- removal of marshy land which created a mosquito menace;

- enlargement of dry land for agriculture and building.

Perth streets were often sandy bogs which caused Governor James Stirling in 1837 to report to the Secretary of State for Colonies:

At the present time it can scarcely be said that any roads exist, although certain lines of communication have been improved by clearing them of timber and by bridging streams and by establishing ferries in the broader parts of the Swan River ...

Parts of the river required dredging with the material dumped onto the mud flats to raise the adjoining land. An exceptionally wet winter in 1862 saw major flooding throughout the area – the effect of which was exacerbated by the extent of the reclaimed lands. The first bucket dredge in Western Australia was the Black Swan, used between 1872 and 1911 for dredging channels in the river, as well as reclamation.

Notable features

A number of features of the river, particularly around the city, have reshaped its profile since European settlement in 1829:

- Claise Brook – named Clause's Brook on early maps, after Frederick Clause. This was a fresh water creek which emptied the network of natural lakes north of the city. Before an effective sewerage system was built, it became an open sewer which dumped waste directly into the river for many years during the 1800s and early 1900s. The area surrounding has been mainly industrial for most of the period of European settlement and it has a long history of neglect. Since the late 1980s, the East Perth redevelopment has dramatically tidied up the area and works include a landscaped inlet off the river large enough for boats. The area is now largely residential and the brook exists in name only with the lakes having been either removed or managed by artificial drainage systems.

- Point Fraser – early maps showed this as a major promontory on the northern side of the river west of the Causeway. It disappeared between 1921 and 1935 when land fill was added on both sides, straightening the irregular foreshore and forming the rectangular 'The Esplanade'.

- The Esplanade – the northern riverbank originally ran close to the base of the escarpment generally a single block width south of St Georges Terrace. Houses built on the southern side of St Georges Terrace included market gardens which ran to the waters edge.

- Heirisson Islands – a series of mudflats that were slightly more upstream from today's single artificial island which has deep channels on each side.

- Burswood – early in the settlement the Perth flats restricted the passage of all but flat bottom boats travelling between Perth and Guildford. It was decided that a canal be built to bypass these creating Burswood Island. In 1831 it took seven men 107 days to do the work. Once completed, it measured about 280 metres (920 ft) in length by an average top width of nearly 9 metres (30 ft) which tapered to 4 metres (13 ft) at the bottom; the depth varied between nearly 1 and 6 metres (3 ft 3 in and 19 ft 8 in). Further improvements were made in 1834. The area on the south side of the river upstream from the causeway was filled throughout the 1900s, reclaiming an area five-times the area of the Mitchell Interchange/Narrows Bridge works.

- Point Belches – later known as Mill Point, South Perth. Originally existed as a sandy promontory surrounding a deep semi-circular bay. This was later named Millers Pool and was eventually filled in and widened to become the present-day South Perth peninsula to which the Narrows Bridge and Kwinana Freeway adjoin.

- Point Lewis (also known as 'One-Tree Point' after a solitary tree that stood on the site for many years) – the northern side of the Narrows Bridge site, and now beneath the interchange.

- Mounts Bay – a modest reclamation was done between 1921 and 1935. In the 1950s works involving the Narrows Bridge started and in 1957 the bay was dramatically reduced in size with works related to the Mitchell Interchange and the northern approaches to the Narrows. An elderly Bessie Rischbieth famously protested against the project by standing in the shallows in front of the bulldozers for a whole day in 1957. She succeeded in halting progress – for that one day.

- Bazaar Terrace/Bazaar Street – in the early days of the settlement this waterfront road between William Street and Mill Street was an important commercial focus with port facilities including several jetties adjoining. It is now approximately where Mounts Bay Road is today and set well back from the foreshore. It had a prominent limestone wall and promenade built using material quarried from Mount Eliza.

- River mouth at Fremantle – the harbour was built in the 1890s and the limestone reef blocking the river was removed at the same time, after 70 years of demands. The dredging of the area to build the Harbour effectively changed the river dynamics from a winter flushing flow to a tidal flushing estuary. It was also at this time that the Helena River was dammed as part of C. Y. O'Connor's ambitious and successful plan to provide water to the Kalgoorlie Goldfields.

Environmental issues

The river has been used for the disposal all kinds of waste. Even well into the 1970s, various local councils had rubbish tips on the mud flats along the edge of the river. Heavy industry also contributed its share of waste into the river from wool scouring plants in Fremantle to fertiliser and foundries sited in the Bayswater – Bassendean area. Remedial sites works are still ongoing in these areas to remove the toxins left to leach into the river.

During the summer months there are problems with algal blooms killing fish and caused by nutrient run-off from farming activities as well as the use of fertilisers in the catchment areas. The occasional accidental spillage of sewage and chemicals has also caused sections of the river to be closed to human access. The river has survived all this and is in relatively good condition considering on-going threats to its ecology.

In 2010 the Western Australian government imposed restrictions on phosphorus levels in fertilisers due to concerns about the health of the Swan and Canning river system.[11]

Flood events

Data collection of flood events in the estuary has been performed since European arrival in 1829. In July 1830, barely a year after the establishment of the colony, the river rose 6 metres (20 ft) above its normal level.[1]: 102 New settlers were still arriving in steady numbers and few permanent buildings had been constructed, with most living in tents and other temporary accommodation. These included caves along the river's edge and many found their belongings washed away and livestock drowned.[12] Other abnormal flooding events occurred in the winters of 1847 and 1860, while the most recent flooding occurred in 2017. Later events have since been assessed for probability of recurrence:

| Year[13] | 1862 | 1872 | 1910 | 1917 | 1926 | 1930 | 1945 | 1946 | 1955 | 1958 | 1963 | 1964 | 1983 | 2017 |

| ARI[lower-alpha 2] | 60 | 100 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 10 | TBC |

The largest recorded flood event was in July 1872 which had a calculated ARI of 100. This approximately equates to a 100-year flood event. At the Helena River, the 1872 flood level was 690 millimetres (2 ft 3 in) higher than the 1862 event (ARI=60). An account in The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal on 26 July 1872 reported[14]

In and about Perth, the water owing to the force of the incoming seas at the mouth of the river presented a scene of a great lake, all the jetties were submerged, the high roads to Fremantle covered, and passage traffic rendered impossible quantities of sandalwood lying along the banks of river were washed away, and the inhabitants of the suburban villas on the slopes of Mount Eliza obliged to scramble up the hill sides to get into Perth.

The flood of July 1926 (ARI=30) resulted in the washing away of the Upper Swan Bridge and a section of the Fremantle Railway Bridge.[15] The Fremantle bridge partially collapsed on 22 July 1926, five minutes after a train containing schoolchildren had passed over.[16] No one was injured in the collapse; however, it created major disruption to commerce for several months. Repairs were completed and the bridge reopened on 12 October 1926.[17]

Governance

The Swan River Trust is a state government body, within the ambit of the Department of Environment and Conservation (Western Australia) – that was constituted in 1989 after legislation passed the previous year, that reports to the Minister for the Environment. It brings together eight representatives from the community, State and local government authorities with an interest in the Swan and Canning rivers to form a single body responsible for planning, protecting and managing Perth's river system.[18][19]

The Trust meets twice a month to provide advice to the Minister for the Environment, the Western Australian Planning Commission and river border related local government bodies to guide development of the Swan and Canning rivers.

Human uses

Transport

In the earliest days of the Swan River Settlement, the river was used as the main transport route between Perth and Fremantle. This continued until the establishment of the Government rail system between Fremantle and Guildford via Perth.

Bridges

There are currently 22 road and railway bridges crossing the Swan River. These are (from Fremantle, heading upstream):[lower-alpha 3]

- Fremantle Railway Bridge, North Fremantle to Fremantle (Fremantle railway line)

- Fremantle Traffic Bridge, North Fremantle to Fremantle

- Stirling Bridge (Stirling Highway), North Fremantle to East Fremantle

- Narrows Bridge, South Perth to Perth (Kwinana Freeway and Mandurah railway line; 2001) – northbound

- Narrows Bridge, Perth to South Perth (Mandurah railway line)

- Narrows Bridge, Perth to South Perth (Kwinana Freeway; 1959) – southbound

- The Causeway (north), Perth to Heirisson Island

- The Causeway (south), Heirisson Island to South Perth

- Matagarup Bridge, East Perth to Perth Stadium, Burswood (pedestrian bridge)

- Goongoongup Bridge, East Perth to Burswood (Armadale railway line)

- Windan Bridge, East Perth to Burswood, (Graham Farmer Freeway)

- Garratt Road Bridge, Bayswater to Ascot – northbound

- Garratt Road Bridge, Ascot to Bayswater (Garratt Road and Grandstand Road) – southbound

- Mooro-Beeloo Bridge, Bayswater to Ascot (Tonkin Highway)

- Bassendean Bridge, Bassendean to Guildford (Guildford Road and Bridge Street)

- Guildford Railway Bridge, Bassendean to Guildford (Midland railway line)

- Barkers Bridge, Guildford to Caversham (Meadow Street and West Swan Road)

- Whiteman Bridge, Caversham to Middle Swan (Reid Highway and Roe Highway)

- Maali Bridge, Henley Brook to Herne Hill (pedestrian bridge; formerly called the Barrett Street Bridge)

- Yagan Bridge, Belhus to Upper Swan (Great Northern Highway; formerly called the Upper Swan Bridge)

- Upper Swan railway bridge, Upper Swan (unnamed)

- Bells Rapids bridge, Upper Swan to Brigadoon (unnamed)

.jpg.webp)

Rowing clubs

The earliest club was the West Australian Rowing Club. The Swan River Rowing Club started in 1887.[20] The Fremantle Rowing Club had started by the 1890s.[21]

Yacht clubs

There are currently fifteen yacht clubs along the Swan River, with most on Melville Water, Freshwater Bay and Matilda Bay. Royal Perth Yacht Club, on Pelican Point in Matilda Bay, staged the unsuccessful 1987 America's Cup defence, the first time in 132 years it had been held outside of the United States. RPYC and the Royal Freshwater Bay Yacht Club are the only two clubs to be granted a royal charter. There are also many anchorages and marinas along the lower reaches near Fremantle.

Cultural significance

The river is a significant part of Perth culture, with many water sports such as rowing, sailing, and swimming all occurring in its waters.

There have been some north of the river or south of the river distinctions in the Perth metropolitan region over time,[22][23] especially in the time up to the completion of the Causeway and Narrows bridges, due to the time and distances to cross the river.

The river was the site of the City of Perth Skyworks, a fireworks show held each year on Australia Day from 1985 until 2022, with spectators crowding the foreshore, Kings Park, and on boats on the river to watch the event.

Aboriginal

The Noongar people believe that the Darling Scarp represents the body of a Wagyl (also spelt Waugal) – a snakelike being from Dreamtime that meandered over the land creating rivers, waterways and lakes. It is thought that the Wagyl/Waugal created the Swan River.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Sharks are present in the river, but rarely attack swimmers. As of February 2023 there have been seven recorded attacks, with two fatalities since 1923.[7]

- ↑ Average recurrence interval (ARI) is the average interval in years which would be expected to occur between exceedances of flood events of a given magnitude.

- ↑ Some of the bridges have had earlier forms that were demolished to make way for the newer bridges.

References

- 1 2 Middelmann; Rogers; et al. (June 2005). "Riverine Flood Hazard" (PDF). Geoscience Australia. Australian Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2011.

- ↑ Rivers of emotion : an emotional history of Derbarl Yerrigan and Djarlgarro Beelier : the Swan and Canning rivers. Broomhall, Susan., Pickering, Gina., Australian Research Council. Centre of Excellence. History of Emotions., National Trust of Western Australia. [Crawley, W.A.]: ARC Centre of Excellence History of Emotions. 2012. ISBN 9781740522601. OCLC 820979809.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Kinsella, John (2017). Polysituatedness: A Poetics of Displacement. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1526113375.

- ↑ Thompson, James (29 December 2017). "Improvements to Swan River navigation 1830–1840". Western Australian Institution of Engineers. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011 – via henrietta.liswa.wa.gov.au Library Catalog.

- ↑ "The Colony of Western Australia. – David Rumsey Historical Map Collection". davidrumsey.com.

- ↑ "Report for Environmental Flows and Objectives Swan and Canning Rivers" (PDF). Swan River Trust. March 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2011.

- 1 2 "WA fisheries minister says bull shark 'likely' behind fatal bite on Perth teenager Stella Berry". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 5 February 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ↑ J.L. Barnard (1972). "Gammaridean Amphipoda of Australia, Part I". Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology (103): 1–333.

- 1 2 Seddon, George & Ravine, David (1986). A City and Its Setting. Fremantle Arts Centre Press. ISBN 978-0-949206-08-4. OCLC 1029292438. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ↑ See also the 1780 usage of the name Black Swan River in – Harmer, T. (17..-18; graveur). Graveur (1780), Plan of the island Rottenest lying off the west coast of New Holland; Black Swan river on New Holland opposite Rottenest island / from Vankeulen; writing by T. Harmar, A. Dalrymple, retrieved 27 December 2013

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "WA goes it alone over phosphorus". 30 April 2010.

- ↑ Kimberly, W. B. (1897). History of Western Australia. p. 55.

- ↑ "Avon River Flood Study: Revision A, prepared by Binnie and Partners Pty Ltd, Perth" (PDF). Public Works Department. 1986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- ↑ "Country News". The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal. 26 July 1872. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Brearley, Anne (2005). Ernest Hodgkin's Swanland: Estuaries and Coastal Lagoons of South-western Australia. Crawley, W. A.: UWAP for the Ernest Hodgkin Trust for Estuary Education and Research and National Trust of Australia (WA). p. 86. ISBN 978-1-920694-38-8.

Re the 1926 flood: floodwaters spread over 5 kilometres at Guildford, and covered large areas of Perth Esplanade, and South Perth... and 12,729 million litres cascaded over Mundaring Weir

- ↑ "THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN FLOODS". The Advertiser. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 23 July 1926. p. 17. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "FREMANTLE RAILWAY BRIDGE". The West Australian. Perth: National Library of Australia. 12 October 1926. p. 7. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "Home page". Swan River Trust. Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ↑ Swan River Trust Act 1988. WA state govt.

- ↑ Child, J (1951), An account of the growth of the Swan River Rowing Club, based on available minute books and gleanings from old members, retrieved 5 October 2018

- ↑ Craig and Solin (1898), Fremantle Rowing Club regatta June 28th 1898, retrieved 5 October 2018

- ↑ Smythe, Phil; Burns, Paul (26 March 2009). "North V South". 1304.5 – Stats Talk WA, Dec 2008. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ↑ "Regions And Cities: Perth metropolitan area". Living in Western Australia. Government of Western Australia. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

Further reading

- Burningham, Nick (2004). Messing About in Earnest. Fremantle Arts Centre Press. ISBN 978-1-920731-25-0.

- Seddon, George (1970). Swan River Landscapes. University of Western Australia: Printing Press. ISBN 978-0-85564-043-9.

- Thompson, James (1911) Improvements to Swan River navigation 1830–1840 [cartographic material] Perth, W.A. : Western Australian Institution of Engineers, 1911. (Perth : Govt. Printer) Battye Library note: – Issued as Drawing no. 1 accompanying Inaugural address by Thompson 31 March 1910 as first president of the Western Australian Institution of Engineers, – Cadastral base map from Lands and Surveys Dept with additions by Thompson showing river engineering works from Burswood to Hierrison [i.e., Heirisson] islands and shorelines as they existed 1830–1840; includes Aboriginal place names along Swan River Estuary.

External links

- Swan River Trust

- Bridging to South Perth by Lloyd Margetts A copy of his speech given to the South Perth Historical Society.

- Historical map of the Swan River

- Swan River Electronic Navigation Chart

- University of Western Australia – Center for Water Research

Media related to Swan River, Western Australia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Swan River, Western Australia at Wikimedia Commons