The swill milk scandal was a major adulterated food scandal in the state of New York in the 1850s. The New York Times reported an estimate that in one year 8,000 infants died from swill milk.[1][2]

Name

Swill milk referred to milk from cows fed swill which was residual mash from nearby distilleries. The milk was whitened with plaster of Paris, thickened with starch and eggs, and hued with molasses.[3]

After the extraction of alcohol from the macerated grain, the residual mash still contains nutrients, and therefore it was an economic advantage to keep cows stabled near distilleries and feed them with swill.[1]

History

The New York Academy of Medicine carried out an examination and established the connection of swill milk with the increased infant mortality in the city.[4][5] The topic of swill milk was also well exposed in pamphlets and caricatures of the time.

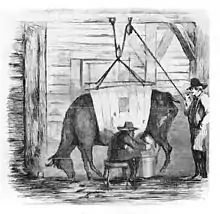

In May 1858, Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper did a landmark exposé of the distillery-dairies of Manhattan and Brooklyn that marketed so-called swill milk that came from cows fed on distillery waste and then adulterated with water, eggs, flour, and other ingredients that increased the volume and masked the adulteration.[6] Swill milk dairies were noted for their filthy conditions and overpowering stench both caused by the close confinement of hundreds (sometimes thousands) of cows in narrow stalls where, once they were tied, they would stay for the rest of their lives, often standing in their own manure, covered with flies and sores, and suffering from a range of virulent diseases. These cows were fed boiling distillery waste, often leaving the cows with rotting teeth and other maladies. The milk drawn from the cows was routinely adulterated with water, rotten eggs, flour, burnt sugar and other adulterants with the finished product then marketed falsely as "pure country milk" or "Orange County Milk".[7][8]

In an editorial published at the height of the scandal, the New York Times described swill milk as a "bluish, white compound of true milk, pus and dirty water, which, on standing, deposits a yellowish, brown sediment that is manufactured in the stables attached to large distilleries by running the refuse distillery slops through the udders of dying cows and over the unwashed hands of milkers..."[1]

Frank Leslie's exposé caused widespread public outrage and local politicians were strongly pressured to punish and regulate the distillery-dairies, which were formally complained to be "swill milk nuisance".[9] The Tammany Hall politician Alderman Michael Tuomey, known as "Butcher Mike", defended the distillers vigorously throughout the scandal—in fact, he was put in charge of the Board of Health investigation. Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper staked out distillery owner Bradish Johnson's mansion at 21st and Broadway, and reported that in the midst of the investigation, Tuomey was observed making late night visits. Tuomey assumed a central role in the ensuing investigations, and, with fellow Aldermen E. Harrison Reed and William Tucker, shielded the dairies and turned the hearings into one-sided exercises designed to make dairy critics and established health authorities look ridiculous, even going to the extent of arguing that swill milk was actually as good or better for children than regular milk.[9] With Reed and others, Tuomey successfully blocked any serious inquiry into the dairies and stymied calls for reform. The Board of Health exonerated the distillers, but public outcry led to the passage of the first food safety laws in the form of milk regulations in 1862.[10] Tuomey became known for his attempts to block the new regulations, and earned the new moniker "Swill Milk" Tuomey.[11] In addition to Tuomey's assistance in clearing up the unclean image milk developed, Robert Milham Hartley, a social reformist, aided in the restoration of milk being a nutritional and safe-to-drink beverage. During the mid to late nineteenth century, Hartley utilized Biblical references in his essays to appeal to the urban community. He asserted that universal milk consumption could help alleviate society's "sins", poverty, and alcohol consumption.[12]

The United States' first pure milk agitator

Robert Hartley was the United States' first consumer advocate and milk agitator. After resigning from his job as a factory manager in Mohawk Valley, New York, Hartley decided to move to New York City, to dedicate his life to joining and establishing many of the city’s major reform organizations: such as, the New York City Temperance Society, The City Mission tract Society, and The New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor (DuPuis). Hartley had a desire to better the lives of humans, which is why he was interested in New York City's poor milk supply.

Hartley's desire to perfect human society provided the basis for his interest in the New York City milk supply. As a temperance reformer, he aimed to eliminate the extra profits provided to the city's brewers through the linked milk and alcohol production systems. As a social reformer interested in the welfare of the poor, he improved the New York milk supply. Beginning in the 1830s in newspaper articles and lectures, and eventually summarized in a publication titled "A Historical, Scientific, and Practical Essay on Milk as an Article of Human Sustenance", Hartley exposed the unsanitary practices of the swill milk system. He was the first American to make a sustained argument that milk was the perfect food.[12]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "How We Poison Our Children" (PDF). New York Times. May 13, 1858. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ "Swill - Milk and Infant Mortality", The New York Times, May 22, 1858

- ↑ Bee Wilson (29 September 2008). "The Swill is Gone". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ↑ Richard A. Meckel (1990). Save the Babies: American Public Health Reform and the Prevention of Infant Mortality, 1850–1929. University of Michigan Press. p. 64. ISBN 0-472-08556-5.

- ↑ Vanderheijden (16 July 1999). International Food Safety Handbook: Science, International Regulation, and Control. CRC Press. p. 651. ISBN 978-0-8247-9354-8.

- ↑ David B. Sachsman; David W. Bulla (2013). Sensationalism: Murder, Mayhem, Mudslinging, Scandals, and Disasters in 19th-Century Reporting. Transaction Publishers. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-4128-5171-8.

- ↑ John Mullaly (1853). The Milk Trade in New York and Vicinity: Giving an Account of the Sale of Pure and Adulterated Milk. Fowlers and Wells. p. 39.

- ↑ Johnson, Steven (2021). Extra Life (1st ed.). Riverhead Books. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-525-53885-1.

- 1 2 "The Swill-Milk Nuisance", The New York Times, June 8, 1858

- ↑ Wilson, Bee (2008). Swindled. Princeton University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780691138206.

- ↑ "They Ought to Be Beaten – "Swill Milk" Tuomey" (PDF). New York Times. October 29, 1878. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- 1 2 DePuis, E. (2002). Nature's Perfect food: How milk became America's Drink. New York: New York University Press.