The Swingin' A's is a nickname for the Oakland Athletics (A's) Major League Baseball team, primarily used in reference to the A's team of the 1970s that dominated the American League from 1972 to 1975, won three consecutive World Series championships in 1972, 1973 and 1974, and is widely recognized as being among the best in baseball history.[1] The team won five consecutive American League West Division titles and three American League pennants en route to their three World Series titles. They were the first team to win three consecutive World Series championships in two decades; no team other than the New York Yankees have completed a three-peat, and no team repeated as champion three times until the Yankees in 2000.

While the team did not record the most appearances in a World Series in the 1970s (as the Cincinnati Reds went to four), the Athletics won more titles overall without losing once; of the six teams who made multiple appearances in the Series of the 1970s, the Athletics and the Pittsburgh Pirates were the only ones to never lose. The Athletics were also the first team in the League Championship Series era (since 1969) to reach it in five consecutive seasons, and they were the second team to win three of them in a row (after the Baltimore Orioles); no team would reach the LCS five straight times until the Atlanta Braves of the 1990s. In their five-year span, they averaged 95 wins while winning their division by at least five games each time. They were characterized by utilizing a tremendous pitching staff to hold precarious leads whenever needed; they scored sixteen, 21, and sixteen runs combined in their respective World Series runs but managed to win each time.[2] In the division era, they are the first and only team to have won the American League West five seasons in a row.

Background

At one point in time, the Athletics organization had achieved success in the city of Philadelphia in the early 20th century. They had reached the World Series five times in nine years before owner Connie Mack dismantled and rebuilt them in the late 1920s, which led to three more World Series appearances. However, their third-place finish in 1933 was the highest they would finish again for over three decades as they would soon be noted as a doormat for both the American League and in the city, and Mack's retirement in 1950 hastened their demise; they moved to Kansas City, Missouri after the 1954 season. The sale of the team from the Macks to Arnold Johnson did little to help their reputation as an also-ran. Johnson's death in 1960 led to a sale to insurance salesman Charlie O. Finley. He attempted to turn a leaf towards trying to put a suitable product on the field, albeit while secretly trying to move the team from the city. He soon became his own general manager the following year while also changing the colors of the team from to Blue to Kelly Green, "Fort Knox" Gold and "Wedding Gown" White. Finley slowly built the nucleus of his team in the mid 1960s that made for a youthful growing core in their farm system, although the Athletics did not have a winning season in the city. He would go through a revolving door of managers who would not last longer than two seasons.

Bert Campaneris and Rollie Fingers were signed in 1964 and Catfish Hunter was signed in 1965. The newly installed entry draft in 1965 resulted in the drafting of Rick Monday (traded later for Ken Holtzman, Gene Tenace and Sal Bando). Reggie Jackson was drafted in 1966, while Vida Blue and Joe Rudi were drafted the following year.

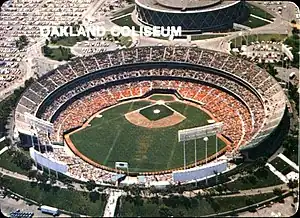

By the time the team moved to Oakland in 1968, the average age of the roster was roughly 24 years old. That season resulted in 82 victories, which was their first winning season since 1952. The following year saw them compete for the newly formed American League West division for a time (although Finley fired Hank Bauer near the end of the year for John McNamara), with the Athletics finishing second by nine games with 88 wins; it was the first time they had back-to-back winning seasons since the 1947-49 years. While Jackson hit 47 home runs in 1969, a slump in the spring had Finley threaten to send him to the minors, although he would end up hitting 23 that year.[3] An 89-win season the following year resulted in the same finish and the dismissal of McNamara. Named to replace him for 1971 was Dick Williams, who was the tenth manager hired by Finley in ten years of ownership.

Dynasty

Williams had played thirteen years of professional baseball before becoming a manager, which included two seasons with Kansas City. He had one previous managerial job before Oakland with the Boston Red Sox (1967–1969), which he led to the American League pennant in 1967 with his aggressive style of managing. Williams once described his team strategy as "We pitch and we catch the ball.’”[4]

The 1971 team came together to roll to 101 victories, the most victories by the club in four decades. They had the fourth best offense in scoring with 691 runs while ranking in the top five in the league in hits and home runs, although they were the only team to have over 1,000 strikeouts. However, their pitching allowed the second fewest runs in the league with 564, while having a team ERA of 3.05 (with only Baltimore being better). Vida Blue, who had pitched just eighteen games combined in his first two seasons, went 24–8 that year with a 1.82 ERA while having eight shutouts (the latter two were league highs) in 312 innings with 301 strikeouts on his way to both the AL Cy Young Award and the AL Most Valuable Player Award. The Athletics won their division by sixteen games over the Kansas City Royals and thus were matched against the other 101-win team in the AL: the Baltimore Orioles, the defending two-time AL champions. The Orioles, which had swept their ALCS opponents in 1969 and 1970, would trounce the Athletics in a sweep, winning 5–3, 5–1, and 5–3 (the Orioles used just one reliever in the series while the Athletics used four). In November, the Athletics attempted to bolster their pitching by trading away Monday to the Chicago Cubs for Ken Holtzman.[5]

In the 1972 season, the Athletics scored the second most runs in the American League with 604, doing so despite having fewer hits than other teams but with the most home runs (134) of all AL teams. They also had the second best team ERA with 2.58 while also allowing the second least amount of runs at 457. They would be matched against the Detroit Tigers, managed by the caustic Billy Martin, which had narrowly beaten Boston by half a game. The 1972 American League Championship Series was a tightly contested one, going the full distance of five games. Oakland won Game 1 with Fingers being tasked to save the game for the last two outs of the ninth inning along with the tenth and eleventh innings. In the eleventh, trailing by one with two on base, Gonzalo Marquez of the Athletics drove a single to right field that scored the tying run before an error by the right fielder scored the winning run. Odom won the second game 5–0 to leave the Athletics one win away as the Series moved to Detroit. However, the Tigers rolled to a 3–0 victory in Game 3. Game 4 saw the A's experience a crushing defeat in which they saw a 3–1 lead in the tenth inning collapse at the hands of three hits by six batters while not getting an out. The pivotal Game 5 matched Odom against Woodie Fryman. Jackson would injure his hamstring in a double steal that saw him knocked out for the rest of the year. A Gene Tenace RBI single broke a 1–1 tie that ultimately proved to be the go-ahead score; Odom went five innings before Vida Blue took over for four innings to help close the game and their first pennant since 1931. The contrast between the Athletics and their opponents, the Cincinnati Reds, in the 1972 World Series led to it being dubbed "The Hairs vs. the Big Squares" (with Oakland referred to as the former). Cincinnati, later dubbed the Big Red Machine, was making its second World Series appearance in three years, having played in 1970 Fall Classic. In a Series that saw the lowest batting average for each team (.209), six of the seven games were decided by just one run. Tenace hit two home runs in Game 1 to rally Oakland to victory (with Blue getting the save) while Joe Rudi hit a home run and made a great catch to help the A's to a Game 2 win (with Fingers getting the save). The A's were outdueled by Jack Billingham in Game 3, but Tenace hit his third home run of the Series in Game 4 and was then part of a ninth inning rally that saw two runs come with three pinch hitters to give Oakland a 3–1 series lead. Tenace hit his fourth and final home run of the Series in Game 5, but a consortium of Reds pitchers held the A's to just four runs while the Reds core rallied on a ninth inning single by Pete Rose; Game 6 was the only rout of the Series, which ended with the Reds scoring eight runs from the fourth to the seventh inning. Odom was matched against Jack Billingham for the pivotal Game 7 at Riverfront Stadium. Oakland got to a quick start with Tenace providing the first run on a two-out single after a three-base error. Cincinnati tied it in the fifth on a sacrifice fly with the bases loaded. In the sixth, Tenace and Sal Bando each hit RBI doubles to make it 3–1. In the eighth inning, Tony Perez hit a sacrifice fly with the bases loaded to make it 3–2, but the Reds could not get a hit afterwards; Rose committed the final out of the Series on a flyball out as the Athletics won. [6]

In the 1973 season, the Athletics scored 758 runs, most in the American League. Other teams outranked them in hits and home runs, but Oakland had the most runners batted in. They allowed 615 runs in the season, third least among all twelve teams for a 3.29 ERA. Jackson was named Most Valuable Player that season, having hit .293 with 117 RBIs with 32 home runs (the latter two were league highs). They were matched against the 97-win Baltimore Orioles. The teams split the first two contests in Baltimore before it moved to Oakland. In Game 3, they won in eleven innings before Baltimore responded with a 5–4 win to even the series at two. Hunter was sent to start Game 5 and he prevailed with a complete-game shutout.[7] Their opponent was the New York Mets, who had won just 83 games but had displaced the Reds in five games to get to their second World Series in four years. Oakland won Game 1 2–1, but Game 2 was a nightmare contest that lasted four hours and resulted in a 10–7 victory for New York. The A's had to rally from a three-run deficit after six innings, but it came un-done in the eleventh when second baseman Mike Andrews made two errors that resulted in four runs scored in a 10–7 loss. Finley was so angered by what he saw of Andrews that he attempted to have Andrews put on the disabled list (with a fake injury) that would have had him miss the entire Series. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn stepped in and reactivated Andrews. Game 3 saw them win in eleven innings, but the Mets responded with a 6–1 victory in Game 4 (after Rusty Staub hit a three-run shot in the first) and a 2–0 victory in Game 5 (with Odom outdueled by Jerry Koosman). This was the only one of the World Series where the Athletics faced elimination while trailing. Hunter started Game 6 and held the Mets to one run while outdueling Tom Seaver for the win. Holtzman started Game 7 against Jon Matlack and he helped his cause with a double that got him scored by Campaneris on his subsequent home run (the first one of the Series for the A's) that started a four-run rally. Holtman went five innings before Rollie Fingers and Darold Knowles (the first pitcher to pitch in all seven games of a World Series) stepped in to neutralize the Mets. Jackson was named World Series MVP, having hit .310 with a home run and six RBIs.

Williams had grown tired of Finley and his antics, and he attempted to leave his contract to manage the New York Yankees. However, Finley would not budge on the year owed on the contract, which essentially took him out of the game for the 1974 season. In his place was Alvin Dark, who had managed two seasons previously in Kansas City. Even before the season started, the players were ticked at Finley, who had given them their championship rings without a diamond. At any rate, the Athletics went on to win 90 games that year, rolling over a close AL West by five games over the Texas Rangers in a year that saw the AL East champion in Baltimore only win 91. Oakland scored 689 runs (third most in the league) while ranking second in home runs and first in stolen bases with high rates in walks and strikeouts. Their 2.95 team ERA was the best in the AL, and they were the only team to allow less than 600 runs in the season (allowing just 551). Tinges of friction showed in the season, however. Reggie Jackson and Billy North had a locker room fight, and attempts by catcher Ray Fosse to break it up resulted in him getting on the disabled list. Hunter had signed a deal with the A's for two years with the stipulation that payments of $50,000 were to be paid as a life insurance annuity in both seasons. Finley balked at having to pay when he was notified of the $25,000 tax payment that was due immediately (if it was not paid, Hunter could be considered a free agent). He went 25–12 with a league-leading 2.49 earned run average and won the AL Cy Young Award. Oakland met Baltimore once again for the ALCS. The Orioles trounced Oakland 6–3, but the A's would win the next three games in tight fashion, winning 5–0, 1–0, and 2–1 in a series that featured both teams bat under .200.[8] They were matched against the Los Angeles Dodgers, managed by Walter Alston. Around the time of the Series, a member of the Dodgers organization was asked about the talents of the Athletics players. They stated that only Jackson and Hunter were good enough to merit being on their team. Compounding the strangeness of this Series would occur right before Game 1 started, when Blue Moon Odom and Fingers had a fight that required stitches for Fingers and a sprained ankle for Odom. Although the Series would be decided in just five games, it was a tight affair, as four of the games were decided by just one run each; the Dodgers batted .228 to Oakland's .211, but Oakland came though most when needed among the five pitchers (Hunter-Blue-Holtzman-Odom-Fingers) utilized by the A's in the series. He pitched 9+1⁄3 innings and allowed just two runs while earning a win in Game 1 along with two saves that saw him named World Series MVP; perhaps fittingly, Odom was the winning pitcher in the clinching Game 5, which marked the only time the Athletics did not need to compete in seven games to win a World Series.

The Athletics did not seem to have lost a step in the 1975 season. They scored 758 runs, second only to the Boston Red Sox in the AL. They did not have as many hits as other teams, but they ranked second in home runs, runs batted in, and stolen bases. Their 3.27 ERA was second to Baltimore while allowing the least amount of hits while allowing 606 runs (third least). They won the AL West for the fifth straight year in a row by seven games over the Kansas City Royals. They met the Boston Red Sox in the 1975 American League Championship Series. However, the Athletics would be trounced by Boston in three games, losing 7–1, 6–3, and 5–3.

Decline

The Athletics utilized tremendous defense and timely hitting to win their championships, winning twelve World Series games in three years, despite being outscored by a total of 56 to 53.

In the end, the man who merited the most credit for building the key core members that won three championships, ended up being the one associated with its downfall. The disagreements that Finley had with numerous players and managers would come back to haunt him when the reserve clause ended in 1975. Hunter was the first step, as he brought up his breach of contract dispute to arbitration on November 26, 1974.[9] On December 16, arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled him a free agent.[10] Finley had to deal with the fact that any player of his not signed under a multi-year deal would be a free agent after 1976. He decided to try and gut his team before it could be done. It started on April 2, when he traded Jackson and Holtzman to the Baltimore Orioles for three players (most notably Don Baylor).[11] Dark was fired after the end of the 1975 season, with Finley describing him as "too busy with church activities" (this occurred after Dark stated in a church talk that Finley had to accept Jesus Christ as his savior or else he would go to Hell); Finley replaced him with Chuck Tanner.

Finley then tried to sell Rudi and Fingers to the Boston Red Sox and Blue (who he had signed to a deal in order to entice a team) to the New York Yankees (each for cash), but the sales were vetoed by Commissioner of Baseball Bowie Kuhn, who stated it was not in the best interest of baseball. Finley tried to sue and then followed it up by benching the three players, until a near player-strike forced his hand to allow them back on the team. The 1976 team would finish 2+1⁄2 games behind the Kansas City Royals, who started their own run of ALCS appearances. Fingers departed the team after the season, and the following year's team lost 98 games. At last, Blue (who in 1976 hoped Finley would take his last breath soon) was finally traded to the San Francisco Giants for Gary Thomasson, Gary Alexander, Dave Heaverlo, John Henry Johnson, Phil Huffman, Alan Wirth and $300,000 on March 15, 1978.[12] Finley agreed to sell the A's to Walter A. Haas, Jr., president of Levi Strauss & Co. in August 1980 for $12.7 million, owing to troubles with his wife that meant he had to sell the team. [13] In 1981, the Athletics returned to the postseason and returned to the World Series in 1988.

Despite their success in the early to mid 70s, the Athletics never drew well even when the team made it to and won three consecutive World Series titles, averaging only 777,000 fans per season the only time they topped the 1 million mark in fan attendance was in the 1973 and 1975 seasons. Charlie Finley would sell the team to Walter Haas in 1980. Under Haas's ownership, the team would begin to make a profit drawing on average around 1.7 million fans per year and would return to the playoffs again in 1981 and would ultimately return to the World Series in 1988 (losing to Los Angeles) and would win a world title the next year (against San Francisco) in a series interrupted by an earthquake.

Statistics

| Season | Record | Divisional finish | Playoffs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 101–60 | 1st (West) | Lost ALCS to Baltimore Orioles, 3–0 |

| 1972 | 93–62 | 1st (West) | Won ALCS vs. Detroit Tigers, 3–2 Won World Series vs. Cincinnati Reds, 4–3 |

| 1973 | 94–68 | 1st (West) | Won ALCS vs. Baltimore Orioles, 3–2 Won World Series vs. New York Mets, 4–3 |

| 1974 | 90–72 | 1st (West) | Won ALCS vs. Baltimore Orioles, 3–1 Won World Series vs. Los Angeles Dodgers, 4–1 |

| 1975 | 98–64 | 1st (West) | Lost ALCS to Boston Red Sox, 3–0 |

Legacy

Four individuals from the group would be inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame: Jackson, Fingers, Hunter, and Williams.

Sparky Anderson, who managed the Big Red Machine, described that the best World Series in history was not the 1975 World Series that he managed to victory, saying "I'll always maintain that the best Series I was ever involved in was the 1972 World Series against Oakland. That's because those were the two of the finest ball clubs to go against each other that you'll ever see in I don't know how long.” Reggie Jackson called his team the best in a generation, one that dwarfed his later success with the New York Yankees (who won two titles in the latter half of the 1970s).[14][15]

In 2017, MLB Network released a documentary detailing The Swingin' A's that told the story of the group.[16]

Further reading

- Bruce Markusen (1998). Baseball's Last Dynasty: Charlie Finley's Oakland A's. Masters Press. ISBN 1570281882.

- Jason Turbow (2017). Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic: Reggie, Rollie, Catfish, and Charlie Finley's Swingin' A's. Houston Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 9780544303171.

- Roger D. Launius, G. Michael Green (2010). Charlie Finley: The Outrageous Story of Baseball's Super Showman. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0802778574.

- Nancy Finley (2016). Finley Ball: How Two Baseball Outsiders Turned the Oakland A's Into a Dynasty and Changed the Game Forever. Regency Publishing. ISBN 9781621575429.

References

- ↑ "The 1970s Oakland A's Were 'Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic'". Npr.org. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ Holmes, Dan (17 May 2021). "The Mod Style of the Swingin' A's - Baseball Egg". Baseballegg.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ "Times Daily - Google News Archive Search". News.google.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ "A's 1970s dynasty built on incredible arms, refusal to be outpitched". Nbcsports.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ "The Day - Google News Archive Search". News.google.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ "1972 World Series Game 7, Oakland Athletics at Cincinnati Reds, October 22, 1972". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ "1973 American League Championship Series (ALCS) Game 5, Baltimore Orioles at Oakland Athletics, October 11, 1973". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ "1974 ALCS - Oakland Athletics over Baltimore Orioles (3-1)". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ Turbow, Jason. "How Catfish Hunter became MLB's first free agent". Si.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ "The Montreal Gazette - Google News Archive Search". News.google.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ Hickey, John. "A Decade of A's Trades: The 1970s". Si.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ "Seven Players Traded to A's," United Press International (UPI), Thursday, March 16, 1978. Retrieved October 22, 2020

- ↑ "Finley sells Oakland A's". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. August 24, 1980. p. 1C.

- ↑ "A's shut down Big Red Machine in thrilling Game 7". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ "Reggie Jackson claims A's 1970s dynasty better than his Yankees teams". Nbcsports.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ "'The Swingin' A's' highlights dynasty in all its glorious dysfunction". Nbcsports.com. Retrieved 9 January 2022.