| Symphony of Psalms | |

|---|---|

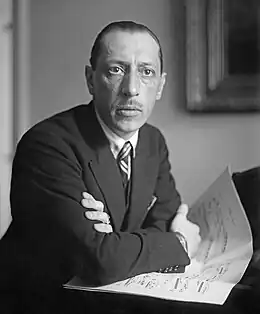

| Choral symphony by Igor Stravinsky | |

| |

| Text | Psalms 39, 40, and 150 |

| Language | Latin |

| Composed | 1930 |

| Movements | Three |

| Scoring | Orchestra and SATB chorus |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 13 December 1930 |

| Location | Brussels, Belgium |

| Conductor | Ernest Ansermet |

| Performers | Société Philharmonique de Bruxelles |

The Symphony of Psalms is a choral symphony in three movements composed by Igor Stravinsky in 1930 during his neoclassical period. The work was commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. The symphony derives its name from the use of Psalm texts in the choral parts.

History

According to Stravinsky, the commission for the work came about from "a routine suggestion" from Koussevitzky, who was also Stravinsky's publisher, that he write something "popular" for orchestra without chorus. Stravinsky, however, insisted on the psalm-symphony idea, which he had had in mind for some time. The choice of Psalm 150, however, was in part because of the popularity of that text. The symphony was written in Nice, and Echarvines near Talloires, which was Stravinsky's summer home in those years.[1] The three movements are performed without break, and the texts sung by the chorus are drawn from the Vulgate versions in Latin. Unlike many pieces composed for chorus and orchestra, Stravinsky said that it is not "a symphony in which I have included psalms to be sung." On the contrary, "it is the singing of psalms that I am symphonizing."[2]

Although the piece was written for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the world premiere was actually given in Brussels by the Société Philharmonique de Bruxelles on December 13, 1930, under the direction of Ernest Ansermet. The American premiere of the piece was given soon afterwards by Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, with the chorus of the Cecilia Society (trained by Arthur Fiedler) on December 19, 1930.[3] The first recording was made by Stravinsky himself with the Orchestre des Concerts Straram and the Alexis Vlassov Choir at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris on February 17 and 18, 1931.[4] One reviewer wrote, "The choir, throaty, full-blooded, darkly, inwardly passionate, sing with liturgical conviction and intensity in a memorable performance."[5]

General analysis

Like many of Stravinsky's other works, including Petrushka and The Rite of Spring, the Symphony of Psalms occasionally employs the octatonic scale (which alternates whole steps and half steps), the longest stretch being eleven bars between rehearsal numbers 4 and 6 in the first movement.[6] Stravinsky stated that the root of the entire symphony is "the sequences of two minor thirds joined by a major third... derived from the trumpet-harp motive at the beginning of the allegro in Psalm 150".[7]

Stravinsky portrays the religious nature of the text through his compositional techniques. He wrote substantial portions of the piece in fugal counterpoint, which was used widely in the church in the Renaissance and Baroque periods. He also uses the large chorus to create a ritual atmosphere like that of the Church.

Instrumentation

The work is scored for the following instrumentation:

|

|

In the score preface, Stravinsky stated a preference for children's voices for the upper two choral parts.

Movements

First movement

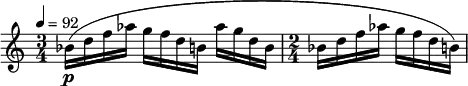

The first movement of the Symphony of Psalms is marked "Tempo ![]() = 92" and uses the text from Psalm 38, verses 13 and 14. This movement was finished on August 15, 1930, which is the feast of the Assumption in the Catholic Church and is written as a prelude to the second movement, a double fugue.

= 92" and uses the text from Psalm 38, verses 13 and 14. This movement was finished on August 15, 1930, which is the feast of the Assumption in the Catholic Church and is written as a prelude to the second movement, a double fugue.

The movement is composed of flowing ostinato sections punctuated with E-minor block chords, in a voicing known as the "Psalms chord", which stop the constant motion.

The first ostinato section in measure 2, which is played in the oboe and bassoon, could be six notes from the octatonic scale starting C♯–D–E–F, etc., but incomplete sets such as this illustrate the controversial nature of the extent of its use.[8] Stravinsky himself regarded this ostinato as "the root idea of the whole symphony", a four-note set consisting of a sequence of "two minor thirds joined by a major third", and stated that it initiated in the trumpet–harp motive at the beginning of the allegro section of the third movement, which was composed first.[7]

If a liturgical character is produced by the use of modal scales even before the chorus's entrance (in measures 12–13, the piano plays an F Dorian scale and in measures 15–16, the piano plays in the E Phrygian mode), it was not a conscious decision:

I was not aware of "Phrygian modes," "Gregorian chants," "Byzantinisms," or anything else of the sort, while composing this music, though, of course, the "influences" said to be denoted by such script-writers' baggage-stickers may very well have been operative.[7]

The presence of the chorus is used to create a church-like atmosphere in this piece as well as to appropriately set the Psalm. It enters with a minor-second motif, which is used both to emphasize the C♯/D octatonic scale and set the pleading text. The minor second motif in the chorus is continued throughout the movement. The use of the octatonic scale and the church modes pervade the sound of the movement, contributing to both the ritual feel of the piece and the plaintive setting of the text.

There are various ways of analyzing the tonal structure of the first movement. The most popular analysis is to view the movement in E minor, pronounced at the opening chord.[9] The following arpeggios on B♭7 and G7 act as dominants to the other tonal centers in the next two movements, E♭ and C respectively. However, the strong presence of G in the movement also points to another tonal center. The opening chord is orchestrated in such a way so that the third of E minor, G, is emphasized. Moreover, the movement concludes with a loud G-major chord, which becomes the dominant to C minor at the start of the second movement.[10]

| Latin (Vulgate) | English (Douay-Rheims) |

Exaudi orationem meam, Domine, et deprecationem meam; auribus percipe lacrimas meas. Ne sileas, quoniam advena ego sum apud te, et peregrinus sicut omnes patres mei. |

Hear my prayer, O Lord, and my supplication: give ear to my tears. Be not silent: for I am a stranger with thee, and a sojourner as all my fathers were. |

Second movement

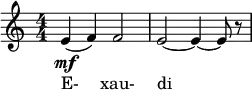

The second movement is a double fugue in C minor,[11] and uses as text Psalm 39, verses 2, 3, and 4. The first fugue theme is based on the same four-note cell used in the first movement,[11] and begins in the oboe in measure one:

The first entrance of the second theme starts in measure 29 in the soprano, followed by an entrance in the alto in measure 33 a fourth down:

The third and fourth entrances are in the tenor in measure 39 and bass in measure 43. Meanwhile, the first fugue theme can be heard in the bass instruments at the entrance of the soprano at measure 29. A stretto is heard in measure 52 based on the second fugal theme.

At measure 71, the voices sing in homophony on the text "He hath put a new song in my mouth". In the accompaniment, a variation of the first fugue theme is played in stretto. Finally, unison is heard in the voices in measure 84 on the text "and shall put their trust in the Lord." This completes the gradual clarification of texture from counterpoint to unison.

The piece concludes with E♭ as the tonal center.[12] Some analyses interpret the E♭ as being part of an inverted C-minor chord which creates a suitable transition into the third movement in C.[13]

| Latin (Vulgate) | English (Douay-Rheims) |

Expectans expectavi Dominum, et intendit mihi. |

With expectation I have waited for the Lord, and he was attentive to me. |

Third movement

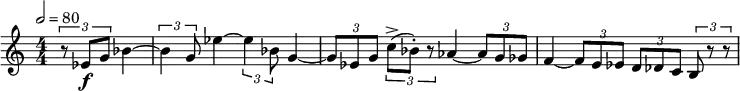

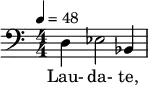

The third movement of the Symphony of Psalms alternates "Tempo ![]() = 48" and "Tempo

= 48" and "Tempo ![]() = 80", and uses nearly the complete text of Psalm 150. Stravinsky wrote:

= 80", and uses nearly the complete text of Psalm 150. Stravinsky wrote:

The allegro in Psalm 150 was inspired by a vision of Elijah's chariot climbing the Heavens; never before had I written anything quite so literal as the triplets for horns and piano to suggest the horses and chariot.[14]

The triplets passage is:

Stravinsky continues by saying:

The final hymn of praise must be thought of as issuing from the skies; agitation is followed by the calm of praise. In setting the words of this final hymn I cared only for the sounds of the syllables and I have indulged to the limit my besetting pleasure of regulating prosody in my own way.[15]

The second part of the slow opening introduction, setting the word "Laudate Dominum", was originally composed to the Old Slavonic words "Gospodi Pomiluy", and Stravinsky regarded this as his personal prayer to the Russian Ecumenical image of the Infant Christ with the scepter and the Globe.[15]

| Latin (Vulgate) | English (Douay-Rheims) |

Alleluia. Laudate Dominum in sanctis ejus; laudate eum in firmamento virtutis ejus. |

Alleluia. Praise ye the Lord in his holy places: praise ye him in the firmament of his power. |

Sergei Prokofiev's use of the text in Alexander Nevsky

When writing music for Sergei Eisenstein's film Alexander Nevsky, Prokofiev needed a Latin text to characterise the invading Teutonic knights. The nonsensical text, peregrinus expectavi pedes meos in cymbalis, appears in Prokofiev's cantata, based on the film score, for the movements "The Crusaders in Pskov" and "The Battle on the Ice". Kerr suggests that these words had been lifted by Prokofiev from the Symphony of Psalms – "peregrinus" from Stravinsky's first movement, "expectavi", and "pedes meos" from the second, and "in cymbalis" from the third – as a barb at Stravinsky.[16]

Notes

- ↑ Stravinsky & Craft 1962, 15.

- ↑ Tommasini, Anthony (2003-05-11). "Music: Tuning Up/'Symphony of Psalms'; Stravinsky's Psalm On Psalm Singing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- ↑ Steinberg 2005, 265.

- ↑ Hill & Simeone 2005, 30

- ↑ Wood 1993.

- ↑ Berger 1963, 40.

- 1 2 3 Stravinsky & Craft 1962, 16

- ↑ Tymoczko 2002, 90–91.

- ↑ Cole 1980, 4.

- ↑ Kang 2007, 9.

- 1 2 Berger 1963, 32

- ↑ Steinberg 2005, 268.

- ↑ Kang 2007, 21.

- ↑ Stravinsky & Craft 1963, 78.

- 1 2 Stravinsky & Craft 1962, 17.

- ↑ Kerr 1994.

Sources

- Berger, Arthur (Autumn–Winter 1963). "Problems of Pitch Organization in Stravinsky". Perspectives of New Music. 2 (1): 11–42. doi:10.2307/832252. JSTOR 832252. Reprinted in Perspectives on Schoenberg and Stravinsky, 2nd edition, edited by Benjamin Boretz and Edward T. Cone, 123–154. New York: W. W. Norton, 1972.

- Cole, Vincent Lewis (1980). Analyses of 'Symphony of Psalms' (1930, rev. 1948) and 'Requiem Canticles' (1966) by Igor Stravinsky (Ph.D., Music Theory). University of California at Los Angeles.

- Hill, Peter; Simeone, Nigel (2005). Messiaen. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10907-5.

- Kang, Jin Myung (2007). An Analysis of Stravinsky's Symphony of Psalms Focusing on Tonality and Harmony (DMA diss). Columbus: Ohio State University. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- Kerr, Morag G (October 1994). "Prokofiev and His Cymbals". The Musical Times. 135 (1820): 608–609. doi:10.2307/1003123. JSTOR 1003123. Text also available at "Alexander Nevsky and the Symphony of Psalms". 6 May 2003. Archived from the original on January 9, 2009. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- Steinberg, Michael (2005). Choral Masterworks: A Listener's Guide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512644-0.

- Stravinsky, Igor; Craft, Robert (Autumn 1962). "A Quintet of Dialogues". Perspectives of New Music. 1 (1): 7–17. doi:10.2307/832175. JSTOR 832175.

- Stravinsky, Igor; Craft, Robert (1963). Dialogues and a Diary. New York: Doubleday. Reprinted London: Faber, 1968; reissued by Faber in 1982 without the Diary section, as Dialogues.

- Tymoczko, Dmitri (2002). "Stravinsky and the Octatonic: A Reconsideration". Music Theory Spectrum. 24 (1): 68–102. doi:10.1525/mts.2002.24.1.68.

- White, Eric Walter (1966). Stravinsky: The Composer and His Works. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press. LCCN 66-27667.

- Wood, Hugh (1993). Igor Stravinsky – Plays & Conducts. Composers in Person. EMI Classics. D202405. Igor Stravinsky – Plays & Conducts at Discogs

Further reading

- Anon. (n.d.). "Symphony of Psalms". Archived from the original on September 12, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- Gielen, Michael. Stravinsky: Symphony in 3 Movements, Symphony in C, and Symphony of Psalms. South West German Radio Symphony Orchestra and West German Radio Chorus, Hanssler.

- Heinemann, Stephen. 1998. "Pitch-Class Set Multiplication in Theory and Practice." Music Theory Spectrum 20, no. 1 (Spring): 72–96.

- Holloway, Robin. 1974. "Stravinsky's Self-Concealment". Tempo, New Series, 108:2–10.

- Kuster, Andrew. "Symphony of Psalms". Archived from the original on February 4, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- Van den Toorn, Pieter. 1983. The Music of Igor Stravinsky. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02693-5

- Van den Toorn, Pieter, and Dmitri Tymoczko. 2003. "Colloquy: Stravinsky and the Octatonic – The Sounds of Stravinsky." Music Theory Spectrum 25, no. 1:167–202.

- Walsh, Steven. 1967. '"Stravinsky's Choral Music". Tempo, New Series, 81 (Stravinsky's 85th Birthday): 41–51.

External links

- Symphony of Psalms – Analysis, background, and texts, by Victor Huang

![\relative c'' { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"oboe" \clef treble \key c \minor \time 4/8 \tempo 8 = 60 c8--[\mf \breathe ees--] \breathe b'--[ \breathe d,--~] | d16[ \breathe c(-- ees-.) b'->~] b[ d,( c') ees,(] | b'8) d,16-- r c( ees b') d,( | c') des,( a') c,( bes'8) b,16-- r | r g' bes,( aes') a,( f') aes,( fis') }](../I/42034807c868f73d9b9c303b5bc1d711.png.webp)

![\relative c'' { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"voice oohs" \clef treble \key c \minor \time 4/8 \tempo 8 = 60 \autoBeamOff ees->\mf bes->~ | bes8 bes bes a | aes!4~ aes16[ bes] ces8 | bes ges' f4~ | f8 } \addlyrics { Ex- pec- tans ex- pec- ta- vi DO- MI- NUM, }](../I/6235b7b98bf9af7d59bf4d914228513a.png.webp)