T. P. O'Connor | |

|---|---|

| |

| Father of the House of Commons | |

| In office 14 December 1918 – 18 November 1929 | |

| Speaker | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Burt |

| Succeeded by | David Lloyd George |

| Member of Parliament for Liverpool Scotland | |

| In office 18 December 1885 – 18 November 1929 | |

| Preceded by | New constituency |

| Succeeded by | David Logan |

| Member of Parliament for Galway Borough | |

| In office 27 April 1880 – 18 December 1885 | |

| Preceded by | George Morris Michael Francis Ward |

| Succeeded by | William Henry O'Shea |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 October 1848 Athlone, County Westmeath, Ireland |

| Died | 18 November 1929 (aged 81) London, England |

| Resting place | St Mary's Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green, London |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Paschal (m. 1885) |

| Alma mater | Queen's College Galway |

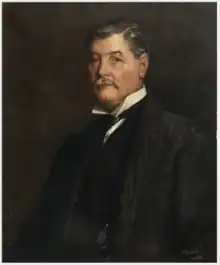

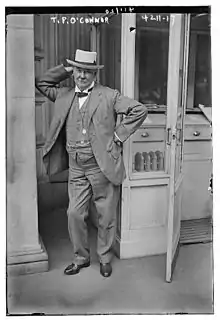

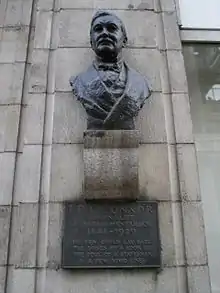

Thomas Power O'Connor, PC (5 October 1848 – 18 November 1929), known as T. P. O'Connor and occasionally as Tay Pay (mimicking his own pronunciation of the initials T. P.), was an Irish nationalist politician and journalist who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland for nearly fifty years.

Early life and education

O'Connor was born in Athlone,[1] County Westmeath, on 5 October 1848. He was the eldest son of Thomas O'Connor, an Athlone shopkeeper, and his wife Teresa (née Power), the daughter of a non-commissioned officer in the Connaught Rangers. He was educated at the College of the Immaculate Conception in Athlone, and Queen's College Galway, where he won scholarships in history and modern languages and built up a reputation as an orator, serving as auditor of the college's Literary and Debating Society.

Career

O'Connor entered journalism as a junior reporter on Saunders' Newsletter, a Dublin journal, in 1867. In 1870, he moved to London, and was appointed a sub-editor on The Daily Telegraph, principally on account of the utility of his mastery of French and German in reportage of the Franco-Prussian War.[1] He later became London correspondent for The New York Herald. He compiled the society magazine Mainly About People (M.A.P.) [2] from 1898 to 1911.

O'Connor was elected Member of Parliament for Galway Borough in the 1880 general election, as a representative of the Home Rule League (which was under the leadership of William Shaw, though virtually led by Charles Stewart Parnell, who would win the party's leadership a short time later). At the next general election in 1885, he was returned both for Galway and for the Liverpool Scotland constituencies, which had a large Irish population. He chose to sit for Liverpool, and represented that constituency in the House of Commons from 1885 until his death in 1929. He remains the only British MP from an Irish nationalist party ever to be elected to a constituency outside of the island of Ireland. O'Connor continued to be re-elected in Liverpool under this label unopposed in the 1918, 1922, 1923, 1924 and 1929 general elections, despite the declaration of a de facto Irish Republic in early 1919, and the establishment by 1921 treaty of a quasi-independent Irish Free State in late 1922.

From 1905, he belonged to the central leadership of the United Irish League.[3] During much of his time in parliament, he wrote a nightly sketch of proceedings there for the Pall Mall Gazette. He became "Father of the House of Commons", with unbroken service of 49 years 215 days. The Irish Nationalist Party ceased to exist effectively after the Sinn Féin landslide of 1918, and thereafter O'Connor effectively sat as an independent. On 13 April 1920, O'Connor warned the House of Commons that the death on hunger strike of Thomas Ashe would galvanise opinion in Ireland and unite all Irishmen in opposition to British rule.[4]

Newspapers and journals

T. P. O'Connor founded and was the first editor of several newspapers and journals: The Star, the Weekly Sun (1891), The Sun (1893), M.A.P. and T.P.'s Weekly (1902). In August 1906, O'Connor was instrumental in the passing by Parliament of the Musical Copyright Act 1906, also known as the T.P. O'Connor Bill, following many of the popular music writers at the time dying in poverty due to extensive piracy by gangs during the piracy crisis of sheet music in the early 20th century.[5][6][7] The gangs would often buy a copy of the music at full price, copy it, and resell it, often at half the price of the original.[8] The film I'll Be Your Sweetheart (1945), commissioned by the British Ministry of Information, is based on the events of the day.[9]

He was appointed as the second president of the Board of Film Censors in 1916 and appeared in front of the Cinema Commission of Inquiry (1916), set up by the National Council of Public Morals where he outlined the BBFC's position on protecting public morals by listing forty-three infractions, from the BBFC 1913–1915 reports, on why scenes in a film may be cut.[10] He was appointed to the Privy Council by the first Labour government in 1924. He was also a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Journalists, the world's oldest journalists' organisation. It continues to honour him by having a T.P. O'Connor charity fund.

Publications

- Lord Beaconsfield – A Biography (1879);

- The Parnell Movement (1886);

- Gladstone's House of Commons (1885);

- Napoleon (1896);

- The Phantom Millions (1902);

- Memoirs of an Old Parliamentarian (1929).

Personal life

In 1885, O'Connor married Elizabeth Paschal, a daughter of a judge of the Supreme Court of Texas.

Death

He died in London on 18 November 1929 and is buried at St Mary's Catholic Cemetery, Kensal Green in north-west London. He was the last Father of the House to die as a sitting MP until Sir Gerald Kaufman in 2017.

References

- 1 2 Dennis Griffiths (ed.) The Encyclopedia of the British Press, 1422–1992, London & Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992, pp.445–46

- ↑ "London Mainly About People Archives, May 27, 1899, p. 3". 27 May 1899.

- ↑ Miller, David W.: Church, State and Nation in Ireland 1898–1921 p.142, Gill & Macmillan (1973) ISBN 0-7171-0645-4

- ↑ Charles Townshend, "The Republic", p.143.

- ↑ Atkinson, Benedict. & Fitzgerald, Brian. (eds.) (2017). Copyright Law: Volume II: Application to Creative Industries in the 20th Century. Routledge. p181.

- ↑ Dibble, Jeremy. (2002). Charles Villiers Stanford: Man and Musician Oxford University press. pp340-341. ISBN 9780198163831

- ↑ Sanjek, Russell. (1988). American Popular Music and Its Business: The First Four Hundred Years. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195043105

- ↑ Johns, Adrian. (2009). Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates. University of Chicago Press. pp349-352. ISBN 9780226401195

- ↑ Johns, Adrian. (2009). Piracy: The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates. University of Chicago Press. p354. ISBN 9780226401195

- ↑ BBFC. 1912–1949: The Early Years at the BBFC: 1916 – T. P. O’CONNOR. Retrieved 14 May 2020

Bibliography

- Boyce, D George (1982). Nationalism in Ireland. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Cottrell, Peter (2008). Irish Civil War, 1922–23. Botley, Oxford.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Walsh, Maurice (2008). The News from Ireland: Foreign Correspondents and the Irish Revolution. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wilson, Trevor, ed. (1970). The Political Diaries of C.P.Scott 1911–1928. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

Media related to T. P. O'Connor at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to T. P. O'Connor at Wikimedia Commons Works by or about Thomas Power O'Connor at Wikisource

Works by or about Thomas Power O'Connor at Wikisource- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by T. P. O'Connor

- Works by T. P. O'Connor at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about T. P. O'Connor at Internet Archive