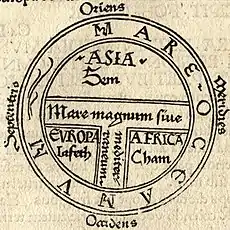

A T and O map or O–T or T–O map (orbis terrarum, orb or circle of the lands; with the letter T inside an O), also known as an Isidoran map, is a type of early world map that represents the physical world as first described by the 7th-century scholar Isidore of Seville in his De Natura Rerum and later his Etymologiae.[1]

Although not included in the original Isidorian maps,[1] a later manuscript added the names of Noah's sons (Sem, Iafeth and Cham) for each of the three continents (see Biblical terminology for race).[1]

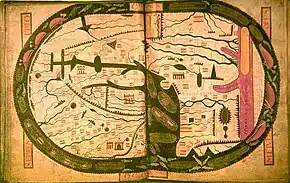

More detailed later maps with equivalent orientation are sometimes described as a "Beatine map" after the Beatus map because one of the earliest known representations of this sort is attributed to Beatus of Liébana, an 8th-century Spanish monk, in the prologue to his Commentary on the Apocalypse.

Isidore's description

De Natura Rerum, Chapter XLVIII, 2 (translation):

So the earth may be divided into three sides (trifarie), of which one part is Europe, another Asia, and the third is called Africa. Europe is divided from Africa by a sea from the end of the ocean and the Pillars of Hercules. And Asia is divided from Libya with Egypt by the Nile... Moreover, Asia – as the most blessed Augustine said – runs from the southeast to the north ... Thus we see the earth is divided into two to comprise, on the one hand, Europe and Africa, and on the other only Asia.[2]

Etymologiae, chapter 14, de terra et partibus:

Latin: Orbis a rotunditate circuli dictus, quia sicut rota est [...] Undique enim Oceanus circumfluens eius in circulo ambit fines. Divisus est autem trifarie: e quibus una pars Asia, altera Europa, tertia Africa nuncupatur.

Etymologiae, chapter 14, de terra et partibus (translation):

The [inhabited] mass of solid land is called round after the roundness of a circle, because it is like a wheel [...] Because of this, the Ocean flowing around it is contained in a circular limit, and it is divided in three parts, one part being called Asia, the second Europe, and the third Africa.[3]

History and description

Although Isidore taught in the Etymologiae that the Earth was "round", his meaning was ambiguous and some writers think he referred to a disc-shaped Earth. However, other writings by Isidore make it clear that he considered the Earth to be globular.[4][5] Indeed, the theory of a spherical Earth had always been the prevailing assumption among the learned since at least Aristotle, who had divided the spherical earth into zones of climate, with a frigid clime at the poles, a deadly torrid clime near the equator, and a mild and habitable temperate clime between the two.

.png.webp)

The T and O map represents only the one half of the spherical Earth.[6] It was presumably considered a convenient projection of known-inhabited parts, the northern temperate half of the globe. It was then believed that no one could cross the torrid equatorial clime and reach the unknown lands on the other half of the globe. These imagined lands were called antipodes.[6][7]

The T is the Mediterranean, the Nile, and the Don (formerly called the Tanais) dividing the three continents, Asia, Europe and Africa, and the O is the encircling ocean. Jerusalem was generally represented in the center of the map. Asia was typically the size of the other two continents combined. Because the Sun rose in the east, Paradise (the Garden of Eden) was generally depicted as being in Asia, and Asia was situated at the top portion of the map.

This qualitative and conceptual type of medieval cartography could yield extremely detailed maps in addition to simple representations. The earliest maps had only a few cities and the most important bodies of water noted. The four sacred rivers of the Holy Land were always present. More useful tools for the traveler were the itinerarium, which listed in order the names of towns between two points, and the periplus that did the same for harbors and landmarks along a seacoast. Later maps of this same conceptual format featured many rivers and cities of Eastern as well as Western Europe, and other features encountered during the Crusades. Decorative illustrations were also added in addition to the new geographic features. The most important cities would be represented by distinct fortifications and towers in addition to their names, and the empty spaces would be filled with mythical creatures.

Gallery

The world map from the Saint-Sever Beatus, dating to ca. AD 1050.

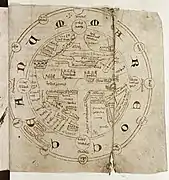

The world map from the Saint-Sever Beatus, dating to ca. AD 1050. From a 12th c. copy of Etymologiae.

From a 12th c. copy of Etymologiae. Map centred on Delos according to Greek tradition, from a French manuscript of Henry of Huntingdon, late 13th century

Map centred on Delos according to Greek tradition, from a French manuscript of Henry of Huntingdon, late 13th century Mappa Mundi in La Fleur des Histoires. 1459–1463.

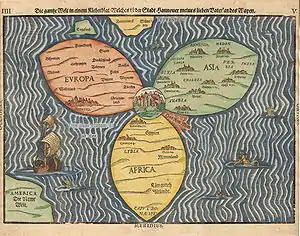

Mappa Mundi in La Fleur des Histoires. 1459–1463. Bünting Clover Leaf Map. A 1581 woodcut, Magdeburg. Jerusalem is in the center, surrounded by Europe, Asia and Africa.

Bünting Clover Leaf Map. A 1581 woodcut, Magdeburg. Jerusalem is in the center, surrounded by Europe, Asia and Africa. Unknown, Mer Des Hystoires World Map, 1491. This map follows the model of the T-O map, centered on Jerusalem with East (the biblical location of Paradise) at the top.

Unknown, Mer Des Hystoires World Map, 1491. This map follows the model of the T-O map, centered on Jerusalem with East (the biblical location of Paradise) at the top. On the left part of the sheet is a zonal or climatic map, communicating geographical information. On the right is a "T-O" map.By Jacobus Philippus Bergomensis.

On the left part of the sheet is a zonal or climatic map, communicating geographical information. On the right is a "T-O" map.By Jacobus Philippus Bergomensis. T and O map accompanied by a V-in-square map, from a copy of the Etymologiae (c. late 8th century).

T and O map accompanied by a V-in-square map, from a copy of the Etymologiae (c. late 8th century).%252C_Isidore-Codex_236.png.webp) From the Saint Gall manuscript

From the Saint Gall manuscript T and O map from the Flemish manuscript of Brunetto Latini, Le Livre dou Tresor, early 14th century.

T and O map from the Flemish manuscript of Brunetto Latini, Le Livre dou Tresor, early 14th century.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Williams 1997, p. 13: "...the Isidoran tradition as it was known from peninsular examples, including the earliest of the ubiquitous T-O maps. This emblematic figure appears twice at the foot of folio 24v in a copy of Isidore's De Natura Rerum, now Escorial R.II.18... The relevant text comes from the concluding passage of the De Natura Rerum, Chapter XLVIII, 2... When, in the ninth century, the Escorial manuscript fell into the hands of Eulogius and was supplemented, this precise text (Etymologiae XIV, 2, 3) was placed on the page, folio 25r, facing the primitive map and was introduced another small T-O map. To this later T-O diagram, however, were added the names of Noah's sons- Shem, Japheth and Ham, for Asia, Europe and Africa, respectively-outside the circle of the globe. This apportionment is only implicit in the Bible (Genesis 9: 18-19). Josephus (d. c.100 AD) is more explicit as was Hippolytus of Rome, whose chronicle of 234 in its Latin translation disseminated the Noachid distribution in the West. Isidore's Etymologiae, however, the distribution of Noah's sons is not highlighted, but only incidentally reported with the description of the location of cities in Book IX. It seems clear, if we accept the evidence of Escorial R.II.18, that the Shem-Japheth-Ham distribution was not in the primitive Isidoran diagram. This means that Isidore's use of the T-O diagram was not informed by any overt religious content."

- ↑ Williams 1997, p. 13.

- ↑ Isidore of Seville (c. 630). Etymologiae (in Latin). Retrieved 10 December 2019.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Stevens, Wesley M. (1980). "The Figure of the Earth in Isidore's 'De natura rerum'". Isis. 71 (2): 268–277. doi:10.1086/352464. JSTOR 230175. S2CID 133430429.

- ↑ Woodward, David. "Reality, Symbolism, Time, and Space in Medieval World Maps", Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 1985, p. 517-519.

- 1 2 Michael Livingston, Modern Medieval Map Myths: The Flat World, Ancient Sea-Kings, and Dragons Archived 2006-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, 2002.

- ↑ Hiatt, Alfred (2002). "Blank Spaces on the Earth". The Yale Journal of Criticism. 15 (2): 223–250. doi:10.1353/yale.2002.0019. S2CID 145164637.

Further reading

- Christoph Mauntel, Die Erdteile in der Weltordnung des Mittelalters. Asien – Europa – Afrika (Monographien zur Geschichte des Mittelalters 71), Hiersemann, Stuttgart 2023.

- Christoph Mauntel, ‘The T-O Diagram and its Religious Connotations – a Circumstantial Case’, in Christoph Mauntel (ed.), Geography and Religious Knowledge in the Medieval World, Berlin/Boston, deGruyter, 2021, pp. 57-82. ISBN 9783110685954

- Crosby, Alfred W. (1996). The Measure of Reality: Quantification in Western Europe, 1250-1600. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-55427-6.

- Lester, Toby (2009). The fourth part of the world: the race to the ends of the Earth, and the epic story of the map that gave America its name. New York, NY: Free Press. ISBN 9781416535317.

- Carlo Zaccagnini, ‘Maps of the World’, in Giovanni B. Lanfranchi et al., Leggo! Studies Presented to Frederick Mario Fales on the occasion of his 65th birthday, Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2012, pp. 865–874. ISBN 9783447066594

- Mode, PJ. "The History and Academic Literature of Persuasive Cartography". Persuasive Cartography, The PJ Mode Collection. Cornell University Library. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- Brigitte Englisch, Ordo orbis terrae. Die Weltsicht in den Mappae mundi des frühen und hohen Mittelalters. Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003635-4

- Williams, John (1997), "Isidore, Orosius and the Beatus Map", Imago Mundi, 49: 7–32, doi:10.1080/03085699708592856, JSTOR 1151330