Tactile hallucination is the false perception of tactile sensory input that creates a hallucinatory sensation of physical contact with an imaginary object.[1] It is caused by the faulty integration of the tactile sensory neural signals generated in the spinal cord and the thalamus and sent to the primary somatosensory cortex (SI) and secondary somatosensory cortex (SII).[2] Tactile hallucinations are recurrent symptoms of neurological diseases such as schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease, Ekbom's syndrome and delirium tremens. Patients who experience phantom limb pains also experience a type of tactile hallucination. Tactile hallucinations are also caused by drugs such as cocaine and alcohol.[1]

History and background

During ancient Greek times, touch was considered to be an unrefined perceptual system because it differed from the other senses on the basis of the distance and timing of perception of the stimulus. Unlike vision and audition, one perceives touch simultaneously with the medium and the stimulus is always proximal and not distal.[1]

By the 17th century, the British empiricist John Locke attributed the word "feeling" with two types of sensation.[1] Weber distinctly identified these two types of sensation as the sense of touch and common bodily sensibility.[1] This distinction further helped 19th century psychiatrists to distinguish between tactile hallucinations and cenesthopathy.

During the 19th century, tactile hallucinations were classified as symptoms associated with insanity, organic and toxic syndromes and delusional parasitosis yet there was no identification on how such hallucinations were caused.[1] Neuroscientists such as Dr. Oliver Sacks and Dr. V.S. Ramachandran have analyzed and attributed tactile hallucinations as a dysfunctional perception of the brain as opposed to just a symptom related to insanity. They have contributed significantly to propose tactile hallucinations as the false perception of tactile sensory input creating a sensation of touch with an imaginary object.

In schizophrenia

Hallucinations of pain and touch are very rare in schizophrenic disorders but 20% of patients with schizophrenia experience some sort of tactile hallucinations along with visual and auditory hallucinations.[3] The most common tactile hallucination in patients with schizophrenia is a sensation in which a patch of their skin is stretched elastically across their head.[4] They vary in intensity, range and speed at which they feel this stretching painful sensation. They are usually triggered by emotional cues such as guilt, anger, fear and depression.[4] Other types of tactile hallucinations takes on a sexual form in patients with schizophrenia. Patients with schizophrenia may sometimes experience the feeling of being kissed or the feeling of someone lying by their side in response to their emotion of being lonely.[1] Additionally, they occasionally hallucinate the feeling of small animals such as snakes crawling over their body.[1] Such vivid tactile sensation of an object that is not present results from the unsuccessful attempt of the brain trying to perceive objects that are novel and that represent unreal situations usually triggered by guilt and fear.[4] Patients with schizophrenia also have a hard time portraying emotions as they divert most of their energy to control the pain from their tactile hallucinations.[4]

Olfactory and tactile hallucinations correlate with one another in terms of prevalence in patients with schizophrenia.[3] One particular study was conducted by Langdon et al., in which the prevalence of olfactory hallucinations and tactile hallucinations was analyzed in two distinct clinical samples of patients with schizophrenia. One of the samples contained patients with schizophrenia with tactile hallucinations as reported by the World Health Organization while the other sample contained cases with negative and positive types of tactile hallucinations in patients with schizophrenia. It was concluded that about 13% to 17% of patients with schizophrenia experience olfactory and tactile hallucinations.[5] The study reported that socio-cultural factors influenced self-reporting of tactile hallucinations. Since hallucinations in general were feared as a symptoms of insanity, patients were reluctant to seek help for such symptoms.[5] Moreover, the study concluded that tactile hallucinations were usually accompanied by several other hallucinations associated with different modalities such as taste and sight.[5] However, the study failed to recognize the pathophysiology of tactile hallucinations in individuals with schizophrenia.

In Parkinson's disease

About 7% of individuals with Parkinson's disease (PD) also experience mild or severe types of tactile hallucinations.[6] Most of these hallucinations are based on the sensation of a particular kind of animal.[6] Several case studies were conducted by Fénelon and his colleagues on patients with PD that had tactile hallucinations. One of his patients described that he sensed "spiders and cockroaches chewing on his lower limb" which was rather painful.[6] Several other patients felt that there was a parasitic infestation of their skin which caused lesions on their skins due to the obsessive need of itching.[6] Fénelon also analyzed the particular types of tactile hallucinations experienced, the timing of such experience and certain drugs that could eliminate such experience. It was concluded that patients with both PD and tactile hallucinations not only experienced sensations elicited by insects under their skin but also by vivid tactile sensations of people.[6] These hallucinations were aggravated during evening times due to altered arousal states and were alleviated by dopaminergic treatment such as the intake of clozapine.[6] The study also explains that the pathophysiology of tactile hallucinations is uncertain, however, such hallucinations can be attributed to narcoleptic rapid eye movement sleep disorders due to its concordance with visual hallucinations.[6] Moreover, it emphasizes that individuals who have had PD for a longer period of time have a more severe form of tactile hallucinations than with individuals who have succumbed to this disease for just a short period of time.[6]

Clinical drugs used as an antiparkinsonian agent such as Trihexyphenidyl are known to create tactile hallucinations in patients with PD.[7][8]

Restless legs syndrome

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) causes unpleasant or uncomfortable sensations in the legs and an irresistible urge to move them.[9][10] Tactile hallucinations in RLS include feelings of itching, pulling, crawling or creeping mainly in the legs, with the accompanying overwhelming urge to move them.[9][10] These symptoms are more prominent in the late afternoon and at night, often causing insomnia.[9] The causes of RLS are generally unknown, though there are three major hypotheses: iron deficiency, dopamine insufficiency and genetic inheritance.[9][10] RLS can also occur due to nerve damage, or neuropathy.[9] Treatments for RLS typically focus on symptom relief through supplementing iron, blocking nerve receptors through the use of alpha-2 delta drugs such as gabapentin, or through the use of opioids or benzodiazepines.[10]

Phantom limbs

Phantom limb pain is a type of tactile hallucination because it creates a sensation of excruciating pain in a limb that has been amputated.[11] In 1996, VS Ramachandran conducted a research on several amputees to pinpoint the neural reasons behind these illusionary pains. Most of these amputees that had an unbearable phantom limb pain are reported by patients whose limb was paralyzed before amputation. VS Ramachandran proposed the "learned paralysis" hypothesis. The hypothesis suggested that every time the patients tried to move their paralyzed limb, they received sensory feedback (through vision and proprioception) that the limb did not move. This feedback hardwired itself into the brain circuitry, so that, even when the limb was no longer present, the brain had learned that the phantom limb was paralyzed.[11] As a treatment for phantom limb pains, VS Ramachandran devised a mirror box that would superimpose the mirror image of the normal arm in place of the missing arm and the patient would immediately be relieved of the pain. This suggested that the brain had a plastic nature in the somatosensory system and the brain had reorganized its somatosensory region to accommodate for this new change.[11] Patients that experience this phantom limb pain are very important in research studies for their role in determining brain plasticity. The vivid tactile sensation of the arm that is no longer present suggest the highly complex nature of the brain to reorganize different functions which were once thought to be hardwired to specific regions (localization).

Inducement through drugs

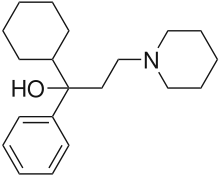

Organic and toxic syndromes can also induce tactile hallucinations. The use of cocaine for recreational purposes has been reported to induce tactile hallucinations.[12] They usually have sensations of moving itches and crawling insects. Cocaine and alcohol can induce rapid firing of neuronal cells of the somatosensory region of the brain leading to vivid perception of illusionary bugs on the skin.[12] Additionally, as mentioned above, Trihexyphenidyl is an antiparkinsonian drug that creates tactile hallucination. The mechanism through which these drugs induce tactile hallucinations is still unknown.

Cenesthopathy

Cenesthopathy is a rare medical term used to refer to the feeling of being ill and this feeling is not localized to one region of the body.[1] Cenesthopathic hallucinatory experiences are caused by the hyperactive neuronal stimulation of the primary somatosensory cortex due to a disorder or a damage to this area. There are two theories that are established to portray sensation of unified bodily feeling. One of these theories is called associationism, which states that cenesthesia is an amalgamation of propioceptive and interoceptive sensations.[1] Faculty psychology is the other theory which states that there is a particular brain region where all of the sensory information converged and the integration of this information gives one cenesthetic sensation. The latter theory became more predominant and it established two types of cenestopathic hallucinations namely "painful" and "paraesthetic". Patients that experience "painful" type of cenesthopathic hallucination felt that their organs were stretched apart and twisted.[1] On the other hand, patients with "paraesthetic" cenesthopathic hallucination experience severe hallucinatory itching.[1]

Pathophysiology

Tactile hallucinations are the result of a dysfunctional somatosensory and a dysfunctional awareness regions of the brain.[2] Tactile sensory input is produced and conducted through the spinal cord and thalamus and it is received at the primary somatosensory cortex. Once it has reached the primary somatosensory cortex, it is distributed across the brain and it will not be processed unless it is important and one pays close attention to the information based on a specific context. Consciousness to these specific tactile sensations is generated only through multiple feedback loops passing through higher cortical areas such as secondary somatosensory area, parietal, insular cortex and premotor areas.[2] The intensity of the tactile stimulus is directly proportional to the area of the primary somatosensory region activated.[13] A feedback mechanism from different cortical areas results in the awareness of touch. Even with complete sensory deprivation, discrete tactile memories can trigger spontaneous firing of impaired neurons.[2] Therefore, individuals with various psychiatric disorders are more prone to tactile hallucinations than normal individuals.

Tactile hallucinations are especially possible due to faulty sensory integration of neuronal signals in the primary and secondary somatosensory system with neuronal signals in the parietal cortex, insular cortex and premotor cortex. Moreover, the posterior insula is responsible for mental body schema representation and can produce tactile hallucination if defected. Additionally, the regions of the brain involved in tactile hallucinations are similar to the regions of the brain involved in pain.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Berrios, G.E. (1982). "Tactile hallucinations: conceptual and historical aspects". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 45 (4): 285–293. doi:10.1136/jnnp.45.4.285. PMC 491362. PMID 7042917.

- 1 2 3 4 Gallace, A.; Spence, C. (2010). "Touch and the body: the role of the somatosensory cortex in tactile awareness". Psyche. 16 (1): 30–60.

- 1 2 Lewandowski, Kathryn E. (2009). "Tactile, olfactory, and gustatory hallucinations in psychotic disorders: a descriptive study". Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 38 (5): 383–385. doi:10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.V38N5p383. PMID 19521636. S2CID 17883653.

- 1 2 3 4 Pfeifer, Louis (1970). "A subjective report of tactile hallucinations in schizophrenia". Journal of Clinical Psychology. 26 (1): 57–60. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(197001)26:1<57::aid-jclp2270260113>3.0.co;2-5. PMID 5411092.

- 1 2 3 Langdon, Robyn; Jonathan McGuire; Richard Stevenson; Stanley V. Catts (2011). "Clinical correlates of olfactory hallucinations in schizophrenia". British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 50 (2): 145–163. doi:10.1348/014466510X500837. PMID 21545448.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Fénelon, Gilles; Stéphane Thobois; Anne-Marie Bonnet; Emmanuel Broussolle; François Tison (2002). "Tactile hallucinations in Parkinson's disease". Journal of Neurology. 249 (12): 1699–1703. doi:10.1007/s00415-002-0908-9. ISSN 1432-1459. PMID 12529792. S2CID 12976293.

- ↑ "Trihexyphenidyl: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- ↑ Funakawa, Itaru; Kenji Jinnai (2005). "Tactile hallucinations induced by trihexyphenidyl in a patient with Parkinson's disease". Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 45 (2): 125–127. PMID 15782612.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Restless Legs Syndrome Fact Sheet | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Kieffer, Sara. "What is Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS)? | The Johns Hopkins Center for Restless Legs Syndrome". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- 1 2 3 Ramachandran, Vilayanur S; William Hirstein (1998). "The perception of phantom limbs. The DO Hebb lecture". Brain. 121 (9): 1603–1630. doi:10.1093/brain/121.9.1603. PMID 9762952.

- 1 2 Morani, Aashish S.; Vikram Panwar; Kenneth Grasing (2013). "Tactile Hallucinations with Repetitive Movements Following Low‐Dose Cocaine: Implications for Cocaine Reinforcement and Sensitization". The American Journal on Addictions. 22 (2): 181–182. doi:10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00336.x. PMID 23414508.

- ↑ Blakemore, SJ; Bristow D; Bird G; Frith C; Ward J (2005). "Somatosensory activations during the observation of touch and a case of vision-touch synaesthesia". Brain. 128 (7): 1571–83. doi:10.1093/brain/awh500. PMID 15817510.