| Tamambo | |

|---|---|

| Malo | |

| Native to | Vanuatu |

| Region | Malo, Espiritu Santo |

Native speakers | 4,000 (2001)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | mla Malo[2] |

| Glottolog | malo1243 |

| ELP | Tamambo |

Tamambo is not endangered according to the classification system of the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Tamambo,[3] or Malo,[1][2] is an Oceanic language spoken by 4,000 people on Malo and nearby islands in Vanuatu. It is one of the most conservative Southern Oceanic languages.[4]

Name

The word Tamambo is the native name of the island of Malo, as pronounced in the western dialect.[5]

In the eastern dialect, the island's name is Tamapo.[5] The same form Tamapo is also used as the name of that eastern dialect of the Tamambo language, now almost extinct.[6][7] Of the same origin is the word R̄am̈apo, which is the name of Malo in the neighboring Araki language.[8]

Phonology

Vowels

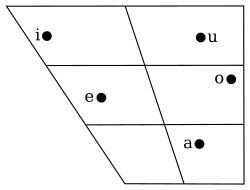

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | i | u |

| Mid | e | o |

| Low | a | |

/i u/ become [j w] respectively when unstressed and before another vowel. /o/ may also become [w] for some speakers.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| labialized | plain | |||||

| Nasal | mʷ | m | n | ŋ | ||

| Plosive | prenasalized | ᵐbʷ | ᵐb | ⁿd | ᶮɟ | |

| plain | t | k | ||||

| Fricative | βʷ | β | s | x | ||

| Trill | r | |||||

| Lateral | l | |||||

The prenasalized postalveolar stop /ᶮɟ/ is often affricated and voiceless, i.e. [ᶮtʃ].

Younger speakers often realize /β/ as [f] initially and [v] medially, while /βʷ/ is often replaced by [w].

/x/ is usually realized as [x] initially, but some speakers use [h]. Medially, it may be pronounced as any of [x ɣ h ɦ ɡ].

Most syllables are of the form CV; closed syllables usually end in a nasal and can also optionally occur in reduplication.

Writing system

Few speakers of Tamambo are literate, and there is no standard orthography. Spelling conventions used include:

| Phoneme | Representation |

|---|---|

| /ᵐb/ | ⟨b⟩ initially, ⟨mb⟩ medially |

| /ᵐbʷ/ | ⟨bu⟩ or ⟨bw⟩ initially, ⟨mbu⟩ or ⟨mbw⟩ medially |

| /x/ | ⟨c⟩ or ⟨h⟩ |

| /ⁿd/ | ⟨d⟩ initially, ⟨nd⟩ medially |

| /ᶮɟ/ | ⟨j⟩ initially, ⟨nj⟩ medially |

| /k/ | ⟨k⟩ |

| /l/ | ⟨l⟩ |

| /m/ | ⟨m⟩ |

| /mʷ/ | ⟨mu⟩ or ⟨mw⟩ |

| /n/ | ⟨n⟩ |

| /ŋ/ | ⟨ng⟩ |

| /r/ | ⟨r⟩ |

| /s/ | ⟨s⟩ |

| /t/ | ⟨t⟩ |

| /β/ | ⟨v⟩ |

| /βʷ/ | ⟨vu⟩ or ⟨w⟩ |

Pronouns and person markers

In Tamambo, personal pronouns distinguish between first, second, and third person. There is an inclusive and exclusive marking on the first-person plural and gender is not marked. There are four classes of pronouns, which is not uncommon in other Austronesian languages:[10]

- Independent pronouns

- Subject pronouns

- Object pronouns

- Possessive pronouns.

| Independent pronouns | Subject pronouns | Object pronouns | Possessive pronouns | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | singular | iau | ku | -(i)au | -ku | |

| plural | inclusive | hinda | ka | -nda | -nda | |

| exclusive | kamam | ka | kamam | -mam | ||

| 2nd person | singular | niho | o | -ho | -m | |

| plural | kamim | no | kamim | -mim | ||

| 3rd person | singular | nia | mo (realis) / a (irrealis) | -a / -e | -na | |

| plural | nira | na | -ra | -ra | ||

Independent pronouns

Independent pronouns behave grammatically similarly to other NPs in that they can occur in the same slot as a subject NP, functioning as the head of a NP. However, in regular discourse, they are not used a great deal due to the obligatory nature of cross-referencing subject pronouns. Use of independent pronouns is often seen as unnecessary and unusual except in the following situations:

- Indicate person and number of conjoint NP

- Introduce new referent

- Reintroduce referent

- Emphasise participation of known referent

Indicating person and number of conjoint NP

In the instance where two NPs are joined as a single subject, the independent pronoun reflects the number of the conjoint NP:

Ku

1SG

vano.

go

'I went.'

and

Nancy

Nancy

mo

3SG

vano.

go

'Nancy went.'

Thus, merging the two above clauses into one, the independent pronoun must change to reflect total number of subjects:

Introducing a new referent

When a new referent is introduced into the discourse, the independent pronoun is used. In this case, kamam:

Ne

But

kamam

1PL.EX

mwende

particular.one

talom,

first

kamam

1PL.EX

ka-le

1PL-TA

loli

do

na

ART

hinau

thing

niaro.

EMPH

'But we who came first, [well] as for us, we do this very thing'[12]

Reintroduction of referent

In this example, the IP hinda in the second sentence is used to refer back to tahasi in the first sentence.

Ka

1PL

tau

put.in.place

tahasi

stone

mo

3SG

sahe,

go.up

le

TA

hani.

burn

Hani

burn

hinda

1PL.IN

ka-le

1PL-TA

biri~mbiri.

REDUP~grate

'We put the stones up (on the fire) and it's burning. While it's burning we do the grating [of the yams].'[13]

Emphasis on participation of known subject

According to Jauncey,[13] this is the most common use of the IP. Comparing the two examples, the latter placing the emphasis on the subject:

O

2SG

vano?

go

'Are you going?'

and

Subject pronouns

Subject pronouns are an obligatory component of a verbal phrase, indicating the person and number of the NP. They can either co-occur with the NP or independent in the subject slot, or exist without if the subject has been deleted through ellipsis or previously known context.

Object pronouns

Object pronouns are very similar looking to independent pronouns, appearing to be abbreviations of the independent pronoun as seen in the pronoun paradigm above. Object pronouns behave similarly to the object NP, occurring in the same syntactic slot, however only one or the other is used, both cannot be used simultaneously as an object argument – which is unusual in Oceanic languages as many languages have obligatory object pronominal cross-referencing on the verb agreeing with NP object.

Possessive pronouns

Possessive pronouns substitute for NP possessor, suffixing to the possessed noun in direct possessive constructions or to one the four possessive classifiers in indirect constructions.

Direct possession

Tama-k

Father-POSS:1SG

mo

3SG

vora

be.born

bosinjivo.

bosinjivo area

'My father was born in the Bisinjivo area.'[17]

Indirect possession

Negation

Negation in Tamambo involves the use of a negative particle; negative verb and negative aspectuals (semantics of time) to change positive constructions into negative ones.

Negation and the VP

The negative particle -te and negative aspectual tele 'not yet' and lete 'never' can appear in the same slot of the Verb Phrase, illustrated below:

| Obligatory (bolded) and optional components of a VP in Tamambo[19] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Subject Pronoun | 2 Modality markers of

Realis mo FUT -mbo |

3 Aspectual

ta |

4 Aspectuals

le male Negative -te Negative Aspectuals tele lete

|

5 Manner modifiers | 6 Head | 7 Manner modifiers

Directionals Non-resultative modifiers |

Both the negative aspectuals appear to be derived from the tense-aspect marker le and the negative particle -te.[19] All the optional modifiers in the VP are mutually exclusive thus; the negative morphemes allow no modifiers between them and the head of the VP.[20]

Negative particle -te

The negative particle -te which expresses negative polarity on the verb[21] is a bound morpheme, meaning it must be attached to the subject pronominal clitic. The negative particle also occurs immediately before the verb noted in example [105].[22] Furthermore, example [105] demonstrates what Jauncey[23] terms a 'negative progressive'; a way of expressing the negative in the present tense such as 'he's not doing it' using the negative particle -te.

Mo-te

3SG-NEG

loli-a

do-OBJ:3SG

'He didn't do it'./ 'He's not doing it.' [105]

Negative aspectuals

The negative aspectuals are used to refer to different aspects of time. The aspectual lete 'never' is used to refer to event times that are prior to speech time noted in example [107] and [100].[19]

Mo

3SG

lete

never

loli-a.

do-OBJ:3SG

'He's never done it.' [107]

Na

3PL

lete

never

skul.

school

'They never went to church.' [100]

The negative aspectual tele 'not yet' is used only where the events are referring to an event time prior to or simultaneous with speech time noted in example [106] and [103].[22]

Mo

3SG

tele

not.yet

loli-a.

do-OBJ:3SG

'He's not yet done it'. [106]

Mo-iso

3SG-finish

na-le

3PL-TA

ovi,

live

na-natu-ra

PL-child-POSS:3PL

na

3PL

tele

not.yet

suiha...

strong

'So then they were living there, (but) their children were not yet strong...' [103]

Negation and modality

In Tamambo, modality can be expressed through the future marker –mbo and the two 3SG subject pronouns, mo (realis) and a (irrealis). In Tamambo realis is 'the grammatical or lexical marking of an event time or situation that has happened (or not) or is happening (or not) relative to speech time' and irrealis refers to 'the grammatical or lexical marking of an event time or situation that may have happened, or that may or may not happen in the future'.[24] In Tamambo, the negative particle -te and aspectual lete can be used in conjunction with the 3SG irrealis a to express that a situation or action is not known to have happened. This is used because the negative markers cannot occur next to the future marker –mbo, however they can occur separately in the same construction evident in example [101][25] containing lete.

Mo

3SG

matahu

frightened

matan

SUB

taura-na

uncle-POSS:3SG

a-te

3SG-NEG

mai.

come

'He is afraid that his uncle might not come.' [97]

Ne

but

are

if

sohen

like

a

3SG

lete

never

lai

take

na

ART

manji,

animal,

a-mbo

3SG-FUT

turu

stand

aie

there

a

3SG

hisi

touch

a

3SG

mate...

die

'But if it was such that he never caught any fish, he would stand there until he died...' [101]

In Tamambo, only the 3SG preverbal subject form has a irrealis, thus when -te is used with other preverbal subject pronouns, the time of event can be ambiguous, and phrases must be understood from context and other lexemes.[26] For example, [98][26] illustrates the various interpretations one phrase may have.

Mo

3SG

matahu

frightened

matan

SUB

bula-na

CLF-POSS:3SG

dam

yam

na-te

3PL-NEG

sula

grow

'S/he is/was afraid that her yams didn't grow/are not growing/won't grow/mightn't grow.' [98]

Negative verb tete

The negative verb tete is a part of Tamambo's closed subset of intransitive verbs, meaning that it has grammatical limitations. For example, the verb tete can only be used in conjunction with the 3SG preverbal subject pronominal clitic. The negative verb tete can function with a valency of zero or one.[27] Valency refers to the number of syntactic arguments a verb can have.

Zero Valency

The most common use of the verb tete is illustrated in example [59],[27] where the verb has zero valency.

Mo

3SG

tete.

negative

'No.' [59]

The 3SG pronoun's of a (irrealis) and mo (realis) are used in conjunction with tete to respond to varying questions depending on whether the answer is certain or not. Example [60][27] illustrates the use of a and tete in a construction to answer a question where the answer is not certain.

A

3SG.IRR

kiri?

rain

A

3SG.IRR

tete.

negative

'Will it/might it rain?' [60] 'No.' [60]

However, if the answer is certain than mo and tete are used highlighted in example [61].[27]

O-mbo

2SG.FUT

vano

go

ana

PREP

maket

market

avuho?

tomorrow

Mo

3SG

tete.

negative

'Are you going to the market tomorrow?' [61] 'No.' [61]

Valency of one

If tete functions with a valency of one, then the intransitive subject must precede the verb similar to a prototypical verb phrase. In this situation, 3SG marking can only represent both the singular and plural, highlighted in example [65].[28]

Tuai,

long.ago

bisuroi

bisuroi.yam

mo

3SG

tete.

negative

'Long ago, there were no bisuroi yams.' [65]

Tete can also function with an 'existential meaning' illustrated in example [62],[27] to express there was 'no one/no people'.

Tuai,

long.ago

Natamabo,

Malo

mo

3SG

tete

negative

tamalohi...

person

'Long ago, on Malo, there were no people...' [62]

Ambient serial verb constructions

The negative verb tete can also be used following a verb in an ambient serial verb construction. In Tamambo, a serial verb construction is defined by Jauncey[29] as 'a sequence of two or more verbs that combine to function as a single predicate'. Furthermore, the term ambient in this verb construction refers to the phenomena when a verb, which follows a transitive or intransitive verb, makes a predication concerning the previous event rather than the participant.[30] When the negative tete verb is used in an ambient serial verb construction, tete makes a negative predication regarding the event expressed by the previous verb highlighted in example [64] and [65].[31] Furthermore, in this instance it is ungrammatical to insert other words between the negative verb and the previous verb.

Tama-na

Father-POSS:3SG

mo

3SG

viti-a

speak-OBJ:3SG

mo

3SG

re

say

"Tamalohi

person

na

3PL

dami-h

ask-OBJ:2SG

mo

3SG

tete"

negative

'Her father spoke to her and said "Men ask for you to no avail." [64]

...ka-te

1PL-NEG

soari-a,

see-OBJ:3SG

ka

1PL

sai-a

search-OBJ:3SG

mo

3SG

tete

negative

'...we didn't see it, we looked for it (but) there was nothing.' [65]

Negation and realis conditional sentences

Negative realis conditional sentences express an idea that something will happen if the condition is not met, such as an imperative or warning. The sentence outlines the conditions, and includes an 'otherwise' or 'if not' component.[32] The condition and the 'if not' (bolded) component occur together before the main clause illustrated in example [124].[32]

Balosuro

present.time

ku

1SG

vuro-ho

fight-OBJ:2SG

hina

PREP

hamba-ku

wing-POSS:1SG

niani

this

o

2SG

laia-a,

take-OBJ:3SG

ro

thus

o

2SG

lai-a

take-OBJ:3SG

ale

if

a-tete-ro

3SG-negative-thus

o

2SG

mate!

die

'(So) now I'm going to fight you with these wings of mine and you defend yourself, so you defend yourself and if not then you're dead!' [124]

Demonstratives

Tamambo distinguishes between demonstrative pronouns, demonstrative adverbs and demonstrative modifiers.

Demonstrative pronouns

Demonstrative pronouns occur in core argument slots, where they occur next to the predicate, can be relativised and can be fronted.[33] These features distinguish them from demonstrative modifiers and demonstrative adverbs which may take the same form.[34] Demonstrative pronouns in Tamambo include pronouns used for spatial deixis, anaphoric reference and emphatic reference.[34] They do not change when referring to animate or inanimate entities.[34]

Spatial deictics

Demonstrative pronouns are organised into a two-way framework, which is based on the distance relative to the speaker and the addressee. While it is common for Oceanic languages to have a distinction based on distance from the speaker, the two-way organisation is unusual for Oceanic languages, where demonstratives usually have a three-way distinction.[35] These pronouns refer to entities which both the speaker and the addressee can see.[34]

niani

The pronoun niani 'this one' refers to an entity which is near the speaker.[34]

niala

The pronoun niala 'that one over there' refers to an entity that is further away from both the speaker and the addressee.[34]

Nirala, which translates to 'those ones over there', is used in colloquial speech as a plural form of niala .[34]

Anaphoric reference

Tamambo, like many other Oceanic languages and possibly Proto-Oceanic, includes a demonstrative system which functions to reference previous discourse.[35] Tamambo includes two pronouns used for anaphora, mwende and mwe, which are only used for anaphora without any marking for person or distance, a common feature of Oceanic languages.[35]

mwende

The pronoun mwende 'the particular one, the particular ones' can function as either a proform or a noun phrase.[34] As shown in example (3) below, mwende is used for a singular noun, specifying which particular knife is the better one, whereas in example (4), the same pronoun, mwende, is referring to multiple 'ones'.

Simba

knife

niala

that

mo

3SG

duhu

good

mo

3SG

liu

exceed

mwende

particular.one

niani.

this

That knife is better than this one.[34]

Mo

3SG

sahe,

go.up

mwende

particular.one

na-le

3PL-TA

turu

stand

aulu

up.direction

na

3PL

revei-a

drag-OBJ:SG

He went up (first) and the ones standing up on top dragged her up.[34]

Emphatic reference

Tamambo includes the demonstrative pronoun, niaro, used for emphasis, as shown in example (5).[36]

Demonstrative adverbs

Spatial modifiers

Spatial modifier adverbs in Tamambo are sentential, and cannot occur within the proposition.[37] There are three sets of spatial modifiers, which are shown in the table below. These three sets of spatial modifiers can be organised into three groups depending on the distance from the speaker, a trait common to demonstratives in Oceanic languages.[35] The following table shows the three sets of spatial modifiers in Tamambo. In this arrangement by Kaufman, the formatives -ni, -e, and -la can be seen to correlate with distance from the speaker.[38]

| Speaker proximate | Hearer proximate | Distal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Set A | aie-n(i) | ai-e | |

| Set B | ro-ni | ro-la | |

| Set C | nia-ni | nia-e | nia-la |

aien and aie

These adverbs begin with ai-, which suggests that they are related to a locative proform in Proto-Oceanic, *ai-.[39] Aien can mean either 'in this place', referring to a location, as shown in example (6), or used for anaphoric reference, where it can mean 'at this stage of events', as shown in example (7). Aien refers to location in place or time more generally than another spatial modifier, roni.[39]

Aie refers to 'another place which is not visible', or may be used for a place which has already been introduced earlier in conversation,[39] as shown in example (8).

roni and rola

Roni is used to refer to a place visible to both the speaker and the listener, and is more specific than aien. It translates to 'right here close to me'.[39]

Rola is an old word for 'there' which is rarely used, and is said to have come from the east.[39] In her research, Jauncey reports no examples of rola being used in narrative or conversation but provides the example below.[39]

niani, niae and niala

These adverbs share the same forms as demonstrative pronouns and modifiers, but they occur at different parts of the sentence and perform different functions. These adverbs refer to places which are visible and in addition, the speaker will point.[40] Niala and niani are not used for anaphoric reference.[40] The nia- component of this set of demonstratives suggests a relationship to the Proto-Austronesian proximate demonstrative, which contains *ni.[38] In addition, the pointing gesture which commonly accompanies the adverbs niani, niae and niala can be derived from the demonstrative function of the Proto-Austronesian component *ni.[41]

Niani translates to 'here', where the referenced entity is close to the speaker, as shown in example (11).[40]

O

2SG

mai

come

ka

1PL

eno

lie

niani

here

ka

1PL

tivovo

cover.over

Come and we'll lie here and cover ourselves...[40]

Niae translates to 'there near you', where the referenced entity is close to the addressee, shown in example (12) below.[40]

Niala translates as 'there' or 'over there', and refers to a place that can be seen or a close place that cannot be seen.[40]

...mwera

male

atea

one

le

TA

ovi

live

aulu

up.direction

niala

there

le

TA

loli-a

do-OBJ:3SG

sohena.

the.same

...a man living up over there (pointing) does it the same way. [40]

Demonstrative modifiers

Demonstrative modifiers are a non-obligatory component of the noun phrase in Tamambo. In Tamambo, demonstrative modifiers function within the noun phrase, after the head noun to modify it. In languages spoken in Vanuatu, and Oceanic languages more generally,[42] the demonstrative commonly follows the head noun. In Proto-Oceanic, this also seems to be the case for adnominal demonstratives.[42] Demonstrative modifiers in Tamambo include spatial reference, anaphoric reference and emphatic reference uses.

Spatial reference

These demonstratives have a three-way distinction, based on distance relative to the speaker.[43] They can occur following the head directly, as shown in example (14), or follow a descriptive adjective, as shown in example (15).[43] The same forms are used as demonstrative pronouns, however niae is not used as a pronoun. The modifiers are the same for singular and plural nouns.[43]

niani

Niani translates to 'this' or 'these' and references something close to the speaker.

In example (14), niani is modifying mwende, the demonstrative pronoun, which is the head.[43]

In this example, the demonstrative modifier niani follows directly after the descriptive adjective tawera, which in turn follows the head noun jara.

niae

Niae refers to something that is close to the addressee, and translates to 'that' or 'those'.[43]

In example (16), the demonstrative modifier niani directly follows the after the noun samburu.

niala

Niala references something that is distant from both the speaker and the addressee.[43]

In example (17), the demonstrative modifier niala follows directly after the first tamalohi, which is the person the speaker is referring to.

Anaphoric referential markers

Tamambo includes two anaphoric referential modifiers, rindi and mwende. Both are used posthead.[44]

rindi

Rindi indicates a noun phrase which has been already introduced in either a preceding clause or earlier string of narrative or conversation, and limits the reference of an entity that has already been introduced.[44]

In example (18), vavine has already been introduced at an earlier stage of the conversation, therefore rindi is used directly following the noun vavine when it is reintroduced.

mwende

Mwende is more specific than rindi and indicates a referent which is definitely known.[44]

Na-re

3PL-say

"Motete,

no

tamalohi

person

mwende

particular.one

mo-ta

3SG-REP

mai

come

They said, "No that particular person hasn't come again."[44]

The demonstrative modifier mwende follows the tamalohi, the noun.

Emphatic reference modifier

Niaro is the only emphatic reference modifier, which can also only occur posthead as shown in example (20).[44]

...vevesai

every

mara-maranjea

REDUP-old.man

nira

3PL

na

3PL

rongovosai

know

na

ART

kastom

custom

niaro

EMPH

...all of the old men know about this very custom.[45]

Niaro can occur with the anaphoric referential modifier rindi, and in that circumstance, rindi is shortened to ri, as shown in example (21) below. Both modifiers follow after the noun Kastom, with the anaphoric reference marker preceding the emphatic reference modifier.[45]

Ro

thus

Kastom

custom

ri

REF

niaro

EMPH

nia

3SG

mo

3SG

tahunju

start

tuai...

of.old

So that particular custom, it started in olden times.[45]

Abbreviations

| 1,2,3 | first, second, third person |

| ART | article |

| CLF | classifier |

| EMPH | emphatic |

| FUT | future |

| IRR | irrealis |

| LINK | possessive linker |

| NEG | negative particle |

| NMZ | nominalising affix |

| OBJ | object pronoun |

| POSS | possessive pronominal |

| PL | plural |

| PREP | preposition |

| REDUP | reduplicated |

| REF | prior reference made |

| REP | repeating action |

| SG | singular |

| SUB | subject |

| TA | tense-aspect marker |

| TR | transitivising suffix |

References

- 1 2 Malo at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- 1 2 "Documentation for ISO 639 identifier: mla". ISO 639-3 Registration Authority - SIL International. Retrieved 2017-07-07.

Name: Malo

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forke, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2020). "Tamambo". Glottolog 4.3.

- ↑ Clark, Ross. 2009. *Leo Tuai: A comparative lexical study of North and Central Vanuatu languages. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics (Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University).

- 1 2 Jauncey (2011:3)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:1, 418)

- ↑ See the introduction to the Tamambo dictionary.

- ↑ See entry R̄am̈apo in the dictionary of Araki.

- ↑ Riehl & Jauncey (2005:256)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:87)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:88)

- 1 2 Jauncey (2011:89)

- 1 2 Jauncey (2011:90)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:91)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:435)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:430)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:434)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:102)

- 1 2 3 Jauncey (2011:323)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:261)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:104)

- 1 2 Jauncey (2011:324)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:262)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:297)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:263, 323)

- 1 2 Jauncey (2011:263)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jauncey (2011:254)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:255)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:325)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:341)

- ↑ Jauncey (2011:343)

- 1 2 Jauncey (2011:416)

- ↑ Jauncey (1997: 61)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Jauncey (1997: 108)

- 1 2 3 4 Ross (1988: 177)

- 1 2 Jauncey (1997: 110)

- ↑ Jauncey (1997: 92)

- 1 2 3 Kaufman (2013: 280)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Jauncey (1997: 93)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Jauncey (1997: 94)

- ↑ Kaufman (2013: 281)

- 1 2 Ross (1988: 179)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Jauncey (1997: 208)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jauncey (1997: 210)

- 1 2 3 Jauncey (1997: 211)

External links

- Materials on Malo are included in the open access Arthur Capell collections (AC1 and AC2) held by Paradisec.

- Jauncey, Dorothy (2011b). "Dictionary of Tamambo, Malo". Retrieved 16 September 2023..

Bibliography

- Dryer, M. (2013). Feature 88A: Order of Demonstrative and Noun. Retrieved 28 March 2021, from https://wals.info/feature/88A#2/16.3/152.9

- Jauncey, Dorothy G. (1997). A Grammar of Tamambo, the Language of Western Malo, Vanuatu (PDF) (Ph.D. thesis). Australian National University. doi:10.25911/5D666220A63B3. hdl:1885/145981.

- Jauncey, Dorothy G. (2002). "Tamambo". In Lynch, J.; Ross, M.; Crowley, T. (eds.). The Oceanic Languages. Richmond, Surrey: Curzon. pp. 608–625.

- Jauncey, Dorothy G. (2011). Tamambo: the Language of Western Malo, Vanuatu (PDF). Pacific Linguistics 622. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. hdl:1885/29991. ISBN 9780858836334.

- Kaufman, Daniel. (2013) “Tamambo, a Language of Malo, Vanuatu, by Dorothy G. Jauncey (Review).” Oceanic Linguistics, 52(1): 277–290. (read online)

- Riehl, Anastasia K.; Jauncey, Dorothy (2005). "Illustrations of the IPA: Tamambo". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (2): 255–259. doi:10.1017/S0025100305002197.

- Ross, Malcolm. (2004) Demonstratives, local nouns and directionals in Oceanic languages: a diachronic perspective, in Gunter Senft (ed.), Deixis and demonstratives in Oceanic Languages, Pacific Linguistics, Canberra, pp. 175 - 204