A tatami (畳) is a type of mat used as a flooring material in traditional Japanese-style rooms. Tatami are made in standard sizes, twice as long as wide, about 0.9 metres (3') by 1.8 metres (6') depending on the region. In martial arts, tatami are the floor used for training in a dojo and for competition.[1]

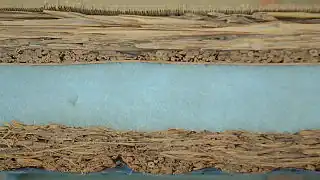

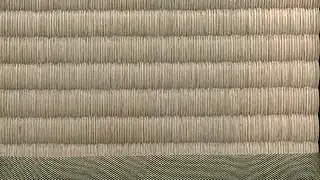

Tatami are covered with a weft-faced weave of soft rush (藺草, igusa) (common rush), on a warp of hemp or weaker cotton. There are four warps per weft shed, two at each end (or sometimes two per shed, one at each end, to cut costs). The doko (core) is traditionally made from sewn-together rice straw, but contemporary tatami sometimes have compressed wood chip boards or extruded polystyrene foam in their cores, instead or as well. The long sides are usually edged (縁, heri) with brocade or plain cloth, although some tatami have no edging.[2][3]

Machine-sewing of tatami

Machine-sewing of tatami Cross-section of a modern tatami with an extruded polystyrene foam core

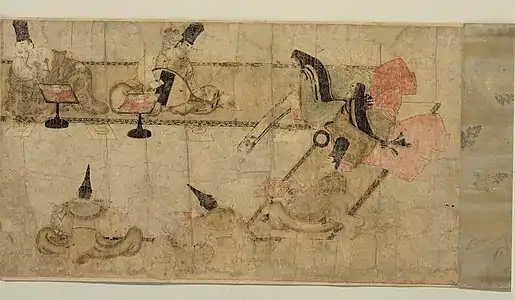

Cross-section of a modern tatami with an extruded polystyrene foam core Making tatami mats, late 19th century.

Making tatami mats, late 19th century. Close-up of mat surface and edging

Close-up of mat surface and edging

History

The term tatami is derived from the verb tatamu (畳む), meaning 'to fold' or 'to pile'. This indicates that the early tatami were thin and could be folded up when not used or piled in layers.[4]

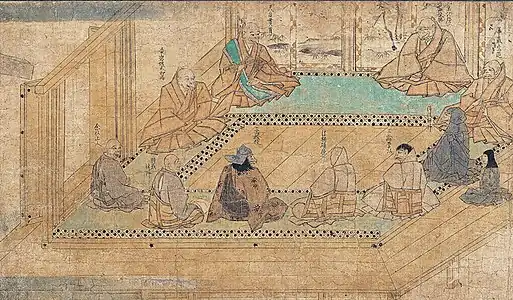

Tatami were originally a luxury item for the nobility. The lower classes had mat-covered earthen floors.[5] During the Heian period, when the shinden-zukuri architectural style of aristocratic residences was consummated, the flooring of shinden-zukuri palatial rooms were mainly wooden, and tatami were only used as seating for the highest aristocrats.[6]

In the Kamakura period, there arose the shoin-zukuri architectural style of residence for the samurai and priests who had gained power. This architectural style reached its peak of development in the Muromachi period, when tatami gradually came to be spread over whole rooms, beginning with small rooms. Rooms completely spread with tatami came to be known as zashiki (座敷, lit. 'spread out for sitting'), and rules concerning seating and etiquette determined the arrangement of the tatami in the rooms.[6]

It is said that prior to the mid-16th century, the ruling nobility and samurai slept on tatami or woven mats called goza (茣蓙), while commoners used straw mats or loose straw for bedding.[7] Tatami were gradually popularized and reached the homes of commoners toward the end of the 17th century.[8]

Houses built in Japan today often have few tatami-floored rooms, if any. Having just one is not uncommon. The rooms having tatami flooring and other such traditional architectural features are referred to as nihonma or washitsu, "Japanese-style rooms".

Size

The size of tatami traditionally differs between regions in Japan:

- Kyoto: 0.955 by 1.91 m (3 ft 1.6 in by 6 ft 3.2 in), called Kyōma (京間) tatami

- Nagoya: 0.91 by 1.82 m (3 ft 0 in by 6 ft 0 in), called Chūkyōma (中京間) or Ainoma (合の間, lit. "in-between" size) tatami

- Tokyo: 0.88 by 1.76 m (2 ft 11 in by 5 ft 9 in), called Edoma (江戸間) or Kantōma (関東間) tatami

In terms of thickness, 5.5 cm (2.2 in) is average for a Kyōma tatami, while 6.0 cm (2.4 in) is the norm for a Kantōma tatami.[6] A half mat is called a hanjō (半畳), and a mat of three-quarter length, which is used in tea-ceremony rooms (chashitsu), is called daimedatami (大目畳 or 台目畳).[4] In terms of traditional Japanese length units, a tatami is (allowing for regional variation) 1 ken by 0.5 ken, or equivalently 6 shaku by 3 shaku – formally this is 1.81818 m × 0.90909 m (72 in × 36 in), the size of Nagoya tatami. Note that a shaku is almost the same length as one foot in the traditional English-American measurement system.

In Japan, the size of a room is often measured by the number of tatami mats (-畳, -jō), about 1.653 m2 (17.79 sq ft) for a standard Nagoya-size tatami. Alternatively, in terms of traditional Japanese area units, room area (and especially house floor area) is measured in terms of tsubo, where one tsubo is the area of two tatami mats (a square); formally 1 ken by 1 ken or about 3.306 m2 (35.59 sq ft).

Some common room sizes in the Nagoya region are:

- 4+1⁄2 mats = 9 shaku × 9 shaku ≈ 2.73 m × 2.73 m (8 ft 11 in × 8 ft 11 in)

- 6 mats = 9 shaku × 12 shaku ≈ 2.73 m × 3.64 m (8 ft 11 in × 11 ft 11 in)

- 8 mats = 12 shaku × 12 shaku ≈ 3.64 m × 3.64 m (11.9 ft × 11.9 ft)

Shops were traditionally designed to be 5+1⁄2 mats, and tea rooms are frequently 4+1⁄2 mats.

A special format is the Ryūkyū (琉球) tatami, which is in square-size and can have various measurements.[9] The Ryūkyū tatami does not have a border and is therefore becoming popular in modern rooms for its simplicity.[10]

Layout

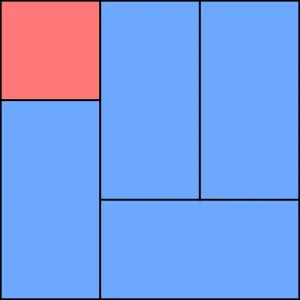

There are rules concerning the number of tatami mats and the layout of the tatami mats in a room. In the Edo period, "auspicious" (祝儀敷き, shūgijiki) tatami arrangements and "inauspicious" (不祝儀敷き, fushūgijiki) tatami arrangements were distinctly differentiated, and the tatami accordingly would be rearranged depending on the occasion. In modern practice, the "auspicious" layout is ordinarily used. In this arrangement, the junctions of the tatami form a "T" shape; in the "inauspicious" arrangement, the tatami are in a grid pattern wherein the junctions form a "+" shape.[6] An auspicious tiling often requires the use of 1⁄2 mats to tile a room.[11] It is NP-complete to determine whether a large room has an auspicious arrangement using only full mats.[12]

An inauspicious layout was used to avoid bringing bad fortune at inauspicious events, such as funerals. However now it is widely associated with bad luck and avoided. [13]

Some auspicious layouts from the early 1800s (Edo Period)

Some auspicious layouts from the early 1800s (Edo Period) One possible auspicious layout of a 4+1⁄2 mat roomHalf matFull mat

One possible auspicious layout of a 4+1⁄2 mat roomHalf matFull mat Typical layout of a 4+1⁄2 mat tea room in the cold season, when the hearth built into the floor is in use. The room has a tokonoma and mizuya dōko

Typical layout of a 4+1⁄2 mat tea room in the cold season, when the hearth built into the floor is in use. The room has a tokonoma and mizuya dōko Room with tatami flooring in an inauspicious layout and paper doors (shōji)

Room with tatami flooring in an inauspicious layout and paper doors (shōji).jpg.webp) An auspicious layout

An auspicious layout.jpg.webp) "T" shape

"T" shape.jpg.webp) Ryūkyū tatami are square shaped without borders

Ryūkyū tatami are square shaped without borders

See also

References

- ↑ "The Quest for the Perfect Judo Floor | Judo Info". judoinfo.com. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ↑ "Understanding Tatami". Motoyama Tatami shop. 28 June 2015. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- ↑ "Structure of Tatami". kyo-tatami.com. Motoyama Tatami Shop. 2015-06-28. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- 1 2 Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, entry for "tatami".

- ↑ "The Yoshino Newsletter". Floors/Tatami. Yoshino Japanese Antiques. Archived from the original on 2007-03-31. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Sato Osamu, "A History of Tatami," in Chanoyu Quarterly no. 77 (1994).

- ↑ Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, entry for "bedding"

- ↑ "Kyoto International Community House Newsletter". 2nd section titled History of tatami. Kyoto City International Foundation. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- ↑ https://www.ryu-kyutatami.com/f/about-ryukyutatami

- ↑ https://www.ikehikojapan.com/blogs/product/l_20210111

- ↑ Erickson, Alejandro; Ruskey, Frank; Schurch, Mark; Woodcock, Jennifer (2010). "Auspicious tatami mat arrangements". In Thai, My T.; Sahni, Sartaj (eds.). Computing and Combinatorics, 16th Annual International Conference, COCOON 2010, Nha Trang, Vietnam, July 19-21, 2010. Proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 6196. Springer. pp. 288–297. arXiv:1103.3309. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-14031-0_32. MR 2720105.

- ↑ Erickson, Alejandro; Ruskey, Frank (2013). "Domino tatami covering is NP-complete". In Lecroq, Thierry; Mouchard, Laurent (eds.). Combinatorial Algorithms: 24th International Workshop, IWOCA 2013, Rouen, France, July 10-12, 2013, Revised Selected Papers. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 8288. Heidelberg: Springer. pp. 140–149. arXiv:1305.6669. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-45278-9_13. MR 3162068. S2CID 12738241.

- ↑ Kalland, Arne (April 1999). "Houses, People and Good Fortune: Geomancy and Vernacular Architecture in Japan". Worldviews. 3 (1): 33–50. doi:10.1163/156853599X00036. JSTOR 43809122.

External links

Media related to Tatami at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tatami at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)