Temple Bar

Barra an Teampaill | |

|---|---|

Neighbourhood of Dublin | |

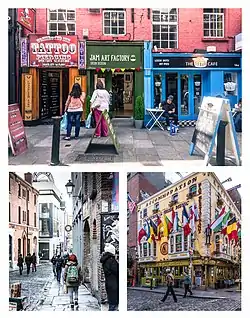

Clockwise from top: Shops along Crown Alley, the OIiver St. John Gogarty bar, pedestrians on Fownes Street | |

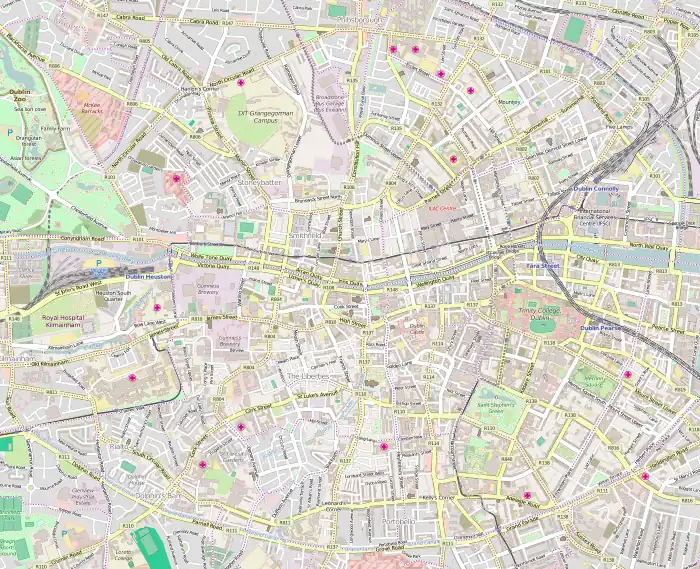

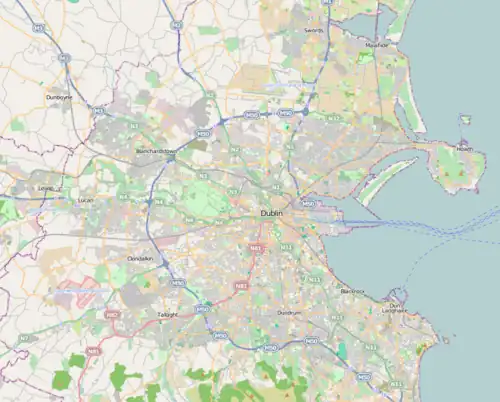

Temple Bar Location in Dublin  Temple Bar Temple Bar (Dublin) | |

| Coordinates: 53°20′44″N 6°15′46″W / 53.34556°N 6.26278°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| City | Dublin |

| Postal district | D02 |

Temple Bar (Irish: Barra an Teampaill)[1] is an area on the south bank of the River Liffey in central Dublin, Ireland. The area is bounded by the Liffey to the north, Dame Street to the south, Westmoreland Street to the east and Fishamble Street to the west. It is promoted as Dublin's 'cultural quarter' and, as a centre of Dublin's city centre's nightlife, is a tourist destination.[2] Temple Bar is in the Dublin 2 postal district.

History

In medieval (Anglo-Norman) times, the name of the district was St. Andrews Parish.[3] It was a suburb, located outside the city walls. But the area fell into disuse beginning in the 14th century because it was exposed to attacks by the native Irish.[3]

The land was redeveloped in the 17th century, to create gardens for the houses of wealthy English families. At that time the shoreline of the River Liffey ran further inland of where it lies today, along the line formed by Essex Street, Temple Bar and Fleet Street. Marshy land to the river side of this line was progressively walled in and reclaimed, allowing houses to be built upon what had been the shoreline; but unusually, the reclaimed land was not quayed, so that the backyards of the houses ran down to the water's edge. (Not until 1812 were these backyards replaced by Wellington Quay.) The fronts of the houses then constituted a new street. The first mention of Temple Bar as the name of this street is in Bernard de Gomme's Map of Dublin from 1673, which shows the reclaimed land and new buildings. Other street names given nearby are Dammas Street (now Dame Street) and Dirty Lane (now Temple Lane South).[3][4]

It is generally thought that the street known as Temple Bar got its name from the Temple family, whose progenitor Sir William Temple built a house and gardens there in the early 1600s.[5] Temple had moved to Ireland in 1599 with the expeditionary force of the Earl of Essex, for whom he served as secretary. (He had previously been secretary of Sir Philip Sydney until the latter was killed in battle.) After Essex was beheaded for treason in 1601, Temple "retired into private life", but he was then solicited to become provost of Trinity College, serving from 1609 until his death in 1627 at age 72. William Temple's son John became the Master of the Rolls in Ireland (a senior judicial position) and was the author of a famous pamphlet excoriating the native Irish population for an uprising in 1641.[6] John's son William Temple became a famous English statesman.[7]

Despite this grand lineage, however, the name of Temple Bar street seems to have been more directly borrowed from the storied Temple Bar district in London, where the main toll-gate into London was located dating back to medieval times.

London's Temple Bar is adjoined by Essex Street to the west and Fleet Street to the east, and streets of the same names occupy similar positions in relation to Dublin's Temple Bar. It seems almost certain therefore that Dublin's Temple Bar was named firstly in imitation of the historic Temple precinct in London. However, a secondary and equally plausible reason for using the name Temple Bar in Dublin would be a reference to one of the area's most prominent families, in a sort of pun or play on words. Or as it has been put more succinctly, Temple Bar 'does honour to London and the landlord in nicely-gauged proportions'.[8]

Fishamble Street near Temple Bar was the location of the first performance of Handel's Messiah on 13 April 1742. An annual performance of the Messiah is held on the same date at the same location. A republican revolutionary group, the Society of the United Irishmen, was formed at a meeting in a tavern in Eustace Street in 1791.

In the 18th century Temple Bar was the centre of prostitution in Dublin.[9] During the 19th century, the area slowly declined in popularity, and in the 20th century, it suffered from urban decay, with many derelict buildings.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the state-owned transport company Córas Iompair Éireann (CIÉ) proposed to buy up and demolish property in the area and build a bus terminus in its place. While that was in the planning stages, the purchased buildings were let out at low rents, which attracted small shops, artists and galleries to the area.[10] The plans included a large underground carpark with 1,500 spaces, a shopping centre on the ground and first floors, with the bus station at second floor level accessed by large, long ramps to accommodate double-decker buses.[11] Protests by An Taisce, residents and traders led to the cancellation of the bus station project, and then Taoiseach Charles Haughey was responsible for securing funding,[12] and, in 1991, the government set up a not-for-profit company called Temple Bar Properties, managed by Laura Magahy, to oversee the regeneration of the area as Dublin's cultural quarter.[13][14]

In 1999, stag parties and hen nights were supposedly banned (or discouraged) from Temple Bar, mainly due to drunken, loutish behaviour, although this seems to have lapsed.[15] However, noise and anti-social behaviour remain a problem at night.[16]

Present day

The area is the location of a number of cultural institutions, including the Irish Photography Centre (incorporating the Dublin Institute of Photography, the National Photographic Archive and the Gallery of Photography), the Ark Children's Cultural Centre, the Irish Film Institute, incorporating the Irish Film Archive, the Button Factory (music venue and club), the Arthouse Multimedia Centre, Temple Bar Gallery and Studios, the Project Arts Centre, the Gaiety School of Acting, IBAT College Dublin, the New Theatre, as well as the Irish Stock Exchange.

At night the area is a centre for nightlife, with various nightclubs, restaurants and bars geared towards tourists. Pubs in the area include The Temple Bar pub, The Porterhouse, The Oliver St. John Gogarty, The Turk's Head, The Quays Bar, The Foggy Dew, The Auld Dubliner, Bad Bobs and Busker's Bar. Bar prices in the Temple Bar area are generally much more expensive than in surrounding areas.

The area has two renovated squares – Meetinghouse Square and the central Temple Bar Square. The Temple Bar Book Market is held on Saturdays and Sundays in Temple Bar Square. Meetinghouse Square, which takes its name from the nearby Quaker Meeting House, is used for outdoor film screenings in the summer months.[17] Since summer 2004, Meetinghouse Square is also home to the 'Speaker's Square' project (an area of public speaking) and to the 'Temple Bar Food Market' on Saturdays.

The 'Cow's Lane Market' is a fashion and design market which takes place on Cow's Lane on Saturdays.[18]

Part of the 13th-century Augustinian Friary of the Holy Trinity is visible within an apartment/restaurant complex called 'The Friary'.[19]

In popular culture

A dance sequence from Bollywood film Ek Tha Tiger was filmed in the area.[20] Irish singer/songwriter Billy Treacy wrote a song about the area,[21] and country singer Nathan Carter as well as Irish rock band Kodaline have released songs called Temple Bar.[22]

See also

References

- ↑ "Barra an Teampaill / Temple Bar". logainm.ie. Irish Placenames Commission. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ↑ "Dublin Quarters - Visit Dublin". visitdublin.com. National Tourism Development Authority (Fáilte Ireland). Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- 1 2 3 Sean Murphy. "A Short History of Dublin's Temple Bar". Bray, County Wicklow: Centre for Irish Genealogical and Historical Studies. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ↑ Dirty Lane was originally called "Hoggen Lane" (i.e. hogs' lane); in the late 1680s it acquired the name "Dirty Lane", and this was then changed to "Temple Lane" in the early 1700s. At that time it was mostly occupied by warehouses and stables, along with the Shakespeare Tavern, "a much frequented establishment". (John T. Gilbert, A History of the City of Dublin, 1859, vol. 2, p. 316.)

- ↑ Maurice Curtis (2016). Temple Bar: A History. History Press Ireland. ISBN 9781845888961.

- ↑ "For One Local Historian, a Rediscovery of Temple Bar". dublininquirer.com. Dublin Inquirer. 10 August 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ↑ John T. Gilbert (1859). A History of the City of Dublin. Vol. 2. pp. 315–316.

- ↑ Murphy, op. cit., quoting National Library of Ireland, '’Historic Dublin Maps'’, Dublin 1988.

- ↑ Niamh O’Reilly. "Striapacha Tri Chead Bliain Duailcis (Prostitutes: Three Hundred Years of Vice)". J Irish Studies. Estudios Irlandeses.

- ↑ McDonald, Frank (1985). The destruction of Dublin. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. p. 194. ISBN 0-7171-1386-8. OCLC 60079186.

- ↑ McDonald, Frank (1989). Saving the city : how to halt the destruction of Dublin. Dublin: Tomar Pub. p. 67. ISBN 1-871793-03-3. OCLC 21019180.

- ↑ "Obituary - Charles Haughey". independent.co.uk. The Independent. 14 June 2006. Archived from the original on 1 April 2010.

- ↑ Temple Bar Framework Plan (Report). Dublin Corporation. 1991.

- ↑ "Temple Bar - Home Page". TempleBar.ie. Archived from the original on 4 December 2003.

Temple Bar Properties is the company established in 1991 to revitalise the area as a Cultural Quarter

- ↑ "Bar Stag Ban Sends Revellers To London". Sunday Mirror. 4 January 1999. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008.

- ↑ "Nightmare in a city that never sleeps". irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 9 September 2008.

- ↑ "The Story of Meeting House Square". meetinghousesquare.ie. Temple Bar Cultural Trust. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ↑ "To market, to market ..." irishtimes.com. Irish Times. 13 November 2003. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ↑ Casey, Christine (2005). Dublin: The City Within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park. Yale University Press. p. 440. ISBN 0300109237.

- ↑ "Bollywood Film 'Ek Tha Tiger' ('I am Tiger') Shoots in Temple Bar, Dublin in October". Film Ireland. 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Kehoe, Michael (13 October 2014). "Singer warns of Dublin tourist trap". Irish Music Daily. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- ↑ "Stayin' Up All Night". nathancartermusic.com. Retrieved 27 July 2016.