| Tendinopathy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | [1] tendinosus[2] |

| |

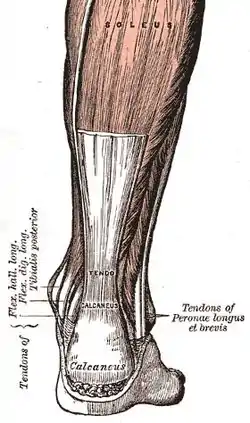

| Achilles tendon (a commonly affected tendon) | |

| Specialty | Primary care |

| Symptoms | Pain, swelling[3] |

| Causes | Injury, repetitive activities[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, examination, medical imaging[4] |

| Treatment | Rest, NSAIDs, splinting, physiotherapy[5] |

| Prognosis | 80% better within 6 months[2] |

| Frequency | Common[3][2] |

Tendinopathy is a type of tendon disorder that results in pain, swelling, and impaired function.[3][1] The pain is typically worse with movement.[6] It most commonly occurs around the shoulder (rotator cuff tendinitis, biceps tendinitis), elbow (tennis elbow, golfer's elbow), wrist, hip, knee (jumper's knee, popliteus tendinopathy), or ankle (Achilles tendinitis).[3][7][2]

Causes may include an injury or repetitive activities.[3] Less common causes include infection, arthritis, gout, thyroid disease, diabetes and the use of quinolone antibiotic medicines.[8][9] Groups at risk include people who do manual labor, musicians, and athletes.[10] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms, examination, and occasionally medical imaging.[4] A few weeks following an injury little inflammation remains, with the underlying problem related to weak or disrupted tendon fibrils.[11]

Treatment may include rest, NSAIDs, splinting, and physiotherapy.[5] Less commonly steroid injections or surgery may be done.[5] About 80% of patients recover completely within six months.[2] Tendinopathy is relatively common.[3] Older people are more commonly affected.[10] It results in a large amount of missed work.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms include tenderness on palpation, swelling, and pain, often when exercising or with a specific movement.[12]

Cause

Causes may include an injury or repetitive activities.[3] Groups at risk include people who do manual labor, musicians, and athletes.[10] Less common causes include infection, arthritis, gout, thyroid disease, and diabetes.[9] Despite the injury of the tendon, there are roads to healing which includes rehabilitation therapy and/or surgery.[13] Obesity, or more specifically, adiposity or fatness, has also been linked to an increasing incidence of tendinopathy.[14]

Quinolone antibiotics are associated with increased risk of tendinitis and tendon rupture.[15] A 2013 review found the incidence of tendon injury among those taking fluoroquinolones to be between 0.08 and 0.2%.[16] Fluoroquinolones most frequently affect large load-bearing tendons in the lower limb, especially the Achilles tendon which ruptures in approximately 30 to 40% of cases.[17]

Types

- Achilles tendinitis

- Calcific tendinitis

- Patellar tendinitis (jumper's knee)

Pathophysiology

As of 2016, the pathophysiology of tendinopathy is poorly understood. While inflammation appears to play a role, the relationships among changes to the structure of tissue, the function of tendons, and pain are not understood and there are several competing models, none of which have been fully validated or falsified.[18][19] Molecular mechanisms involved in inflammation includes release of inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β which reduces the expression of type I collagen mRNA in human tenocytes and causes extracellular matrix degradation in the tendon.[20] However, in a recent systematic review, signs of chronic inflammation, including either the presence of inflammatory cells or an increase in inflammatory markers, were observed in the majority of tendons with tendinopathy.[21]

There are multifactorial theories that could include: tensile overload, tenocyte related collagen synthesis disruption, load-induced ischemia, neural sprouting, thermal damage, and adaptive compressive responses. The intratendinous sliding motion of fascicles and shear force at interfaces of fascicles could be an important mechanical factor for the development of tendinopathy and predispose tendons to rupture.[22]

The most commonly accepted cause for this condition is seen to be an overuse syndrome in combination with intrinsic and extrinsic factors leading to what may be seen as a progressive interference or the failing of the innate healing response. Tendinopathy involves cellular apoptosis, matrix disorganization and neovascularization.[23]

Classic characteristics of "tendinosis" include degenerative changes in the collagenous matrix, hypercellularity, hypervascularity, and a lack of inflammatory cells which has challenged the original misnomer "tendinitis".[24][25]

Histological findings include granulation tissue, microrupture, degenerative changes, and there is no traditional inflammation. As a consequence, "lateral elbow tendinopathy or tendinosis" is used instead of "lateral epicondylitis".[26]

Examination of tennis elbow tissue reveals noninflammatory tissue, so the term "angiofibroblastic tendinosis" is used.[27]

Cultures from tendinopathic tendons contain an increased production of type III collagen.[28][29]

Longitudinal sonogram of the lateral elbow displays thickening and heterogeneity of the common extensor tendon that is consistent with tendinosis, as the ultrasound reveals calcifications, intrasubstance tears, and marked irregularity of the lateral epicondyle. Although the term "epicondylitis" is frequently used to describe this disorder, most histopathologic findings of studies have displayed no evidence of an acute, or a chronic inflammatory process. Histologic studies have demonstrated that this condition is the result of tendon degeneration, which causes normal tissue to be replaced by a disorganized arrangement of collagen. Therefore, the disorder is more appropriately referred to as "tendinosis" or "tendinopathy" rather than "tendinitis".[30]

Colour Doppler ultrasound reveals structural tendon changes, with vascularity and hypo-echoic areas that correspond to the areas of pain in the extensor origin.[31]

Load-induced non-rupture tendinopathy in humans is associated with an increase in the ratio of collagen III:I proteins, a shift from large to small diameter collagen fibrils, buckling of the collagen fascicles in the tendon extracellular matrix, and buckling of the tenocyte cells and their nuclei.[32]

Diagnosis

.jpg.webp)

Symptoms can vary from aches or pains and local joint stiffness, to a burning that surrounds the whole joint around the inflamed tendon. In some cases, swelling occurs along with heat and redness, and there may be visible knots surrounding the joint. With this condition, the pain is usually worse during and after activity, and the tendon and joint area can become stiff the following day as muscles tighten from the movement of the tendon. Many patients report stressful situations in their life in correlation with the beginnings of pain which may contribute to the symptoms.

Medical imaging

Ultrasound imaging can be used to evaluate tissue strain, as well as other mechanical properties.[33] Ultrasound-based techniques are becoming more popular because of its affordability, safety, and speed. Ultrasound can be used for imaging tissues, and the sound waves can also provide information about the mechanical state of the tissue.[34]

Treatment

Treatment of tendon injuries is largely conservative. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), rest, and gradual return to exercise is a common therapy. Resting assists in the prevention of further damage to the tendon. Ice, compression and elevation are also frequently recommended. Physical therapy, occupational therapy, orthotics or braces may also be useful. Initial recovery is typically within two to three days and full recovery is within three to six months.[2] Tendinosis occurs as the acute phase of healing has ended (six to eight weeks) but has left the area insufficiently healed. Treatment of tendinitis helps reduce some of the risks of developing tendinosis, which takes longer to heal.

There is tentative evidence that low-level laser therapy may also be beneficial in treating tendinopathy.[35] The effects of deep transverse friction massage for treating tennis elbow and lateral knee tendinitis is unclear.[36]

NSAIDs

NSAIDs may be used to help with pain.[2] They however do not alter long term outcomes.[2] Other types of pain medication, like paracetamol, may be just as useful.[2]

Steroids

Steroid injections have not been shown to have long term benefits but have been shown to be more effective than NSAIDs in the short term.[37] They appear to have little benefit in tendinitis of the rotator cuff.[38] There are some concerns that they may have negative effects.[39]

Other injections

There is insufficient evidence on the routine use of injection therapies (autologous blood, platelet-rich plasma, deproteinised haemodialysate, aprotinin, polysulphated glycosaminoglycan, skin derived fibroblasts etc.) for treating Achilles tendinopathy.[40] As of 2014 there was insufficient evidence to support the use of platelet-rich therapies for treating musculoskeletal soft tissue injuries such as ligament, muscle and tendon tears and tendinopathies.[41]

Prognosis

Initial recovery is usually within two to three months, and full recovery usually within three to six months. About 80% of people will fully recover within 12 months.[2]

Epidemiology

Tendon injury and resulting tendinopathy are responsible for up to 30% of consultations to sports doctors and other musculoskeletal health providers.[42] Tendinopathy is most often seen in tendons of athletes either before or after an injury but is becoming more common in non-athletes and sedentary populations. For example, the majority of patients with Achilles tendinopathy in a general population-based study did not associate their condition with a sporting activity.[43] In another study the population incidence of Achilles tendinopathy increased sixfold from 1979–1986 to 1987–1994.[44] The incidence of rotator cuff tendinopathy ranges from 0.3% to 5.5% and annual prevalence from 0.5% to 7.4%.[45]

Terminology

Tendinitis is a very common, but misleading term. By definition, the suffix "-itis" means "inflammation of". Inflammation[46] is the body's local response to tissue damage which involves red blood cells, white blood cells, blood proteins with dilation of blood vessels around the site of injury. Tendons are relatively avascular.[47] Corticosteroids are drugs that reduce inflammation. Corticosteroids can be useful to relieve chronic tendinopathy pain, improve function, and reduce swelling in the short term. However, there is a greater risk of long-term recurrence.[48] They are typically injected along with a small amount of a numbing drug called lidocaine. Research shows that tendons are weaker following corticosteroid injections.

Tendinitis is still a very common diagnosis, though research increasingly documents that what is thought to be tendinitis is usually tendinosis.[49]

Anatomically close but separate conditions are:

- Enthesitis, wherein there is inflammation of the entheses, the sites where tendons or ligaments insert into the bone.[50][51] It is associated with HLA B27 arthropathies such as ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, and reactive arthritis.[52][53]

- Apophysitis, inflammation of the bony attachment, generally associated with overuse among growing children.[54][55][56]

Research

The use of a nitric oxide delivery system (glyceryl trinitrate patches) applied over the area of maximal tenderness was found to reduce pain and increase range of motion and strength.[57]

A promising therapy involves eccentric loading exercises involving lengthening muscular contractions.[58]

Other animals

Bowed tendon is a horseman's term for tendinitis (inflammation) and tendinosis (degeneration), most commonly seen in the superficial digital flexor tendon in the front leg of horses.

Mesenchymal stem cells, derived from a horse's bone marrow or fat, are currently being used for tendon repair in horses.[59]

References

- 1 2 "Tendinopathy MeSH Browser". US National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Wilson JJ, Best TM (Sep 2005). "Common overuse tendon problems: A review and recommendations for treatment" (PDF). American Family Physician. 72 (5): 811–8. PMID 16156339. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Tendinitis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- 1 2 "Tendinitis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Tendinitis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ↑ "Tendinitis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ↑ "Tendinitis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ↑ "Fluoroquinolones and risk of Achilles tendon disorders: case-control study". British Medical Journal. 1 June 2002. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- 1 2 "Tendinitis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Tendinitis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ↑ Khan KM, Cook JL, Kannus P, Maffulli N, Bonar SF (2002-03-16). "Time to abandon the "tendinitis" myth: Painful, overuse tendon conditions have a non-inflammatory pathology". BMJ. 324 (7338): 626–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7338.626. PMC 1122566. PMID 11895810.

- ↑ Rees JD, Maffulli N, Cook J (Sep 2009). "Management of tendinopathy". Am J Sports Med. 37 (9): 1855–67. doi:10.1177/0363546508324283. PMID 19188560. S2CID 1810473.

- ↑ Nirschl RP, Ashman ES (2004). "Tennis elbow tendinosis (epicondylitis)". Instr Course Lect. 53: 587–98. PMID 15116648.

- ↑ Gaida JE, Ashe MC, Bass SL, Cook JL (2009). "Is adiposity an under-recognized risk factor for tendinopathy? A systematic review". Arthritis Rheum. 61 (6): 840–9. doi:10.1002/art.24518. PMID 19479698.

- ↑ FDA May 12, 2016 FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA advises restricting fluoroquinolone antibiotic use for certain uncomplicated infections; warns about disabling side effects that can occur

- ↑ Stephenson, AL; Wu, W; Cortes, D; Rochon, PA (September 2013). "Tendon Injury and Fluoroquinolone Use: A Systematic Review". Drug Safety. 36 (9): 709–21. doi:10.1007/s40264-013-0089-8. PMID 23888427. S2CID 24948660.

- ↑ Bolon, Brad (2017-01-01). "Mini-Review: Toxic Tendinopathy". Toxicologic Pathology. 45 (7): 834–837. doi:10.1177/0192623317711614. ISSN 1533-1601. PMID 28553748.

- ↑ Millar, NL; Murrell, GA; McInnes, IB (25 January 2017). "Inflammatory mechanisms in tendinopathy - towards translation". Nature Reviews. Rheumatology. 13 (2): 110–122. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2016.213. PMID 28119539. S2CID 10794196.

- ↑ Cook, JL; Rio, E; Purdam, CR; Docking, SI (October 2016). "Revisiting the continuum model of tendon pathology: what is its merit in clinical practice and research?". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 50 (19): 1187–91. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095422. PMC 5118437. PMID 27127294.

- ↑ Millar, Neal L.; Murrell, George A. C.; McInnes, Iain B. (2017-01-25). "Inflammatory mechanisms in tendinopathy - towards translation". Nature Reviews. Rheumatology. 13 (2): 110–122. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2016.213. ISSN 1759-4804. PMID 28119539. S2CID 10794196.

- ↑ Jomaa G, et al. (2020). "A systematic review of inflammatory cells and markers in human tendinopathy". BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 21 (1): 78. doi:10.1186/s12891-020-3094-y. PMC 7006114. PMID 32028937.

- ↑ Sun YL, et al. (2015). "Lubricin in Human Achilles Tendon: The Evidence of Intratendinous Sliding Motion and Shear Force in Achilles Tendon". J Orthop Res. 33 (6): 932–7. doi:10.1002/jor.22897. PMID 25864860. S2CID 20575820.

- ↑ Charnoff, Jesse; Naqvi, Usker (2017). "Tendinosis (Tendinitis)". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28846334.

- ↑ Fu SC, Rolf C, Cheuk YC, Lui PP, Chan KM (2010). "Deciphering the pathogenesis of tendinopathy: a three-stages process". Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2: 30. doi:10.1186/1758-2555-2-30. PMC 3006368. PMID 21144004.

- ↑ Abate M, Silbernagel KG, Siljeholm C, Di Iorio A, De Amicis D, Salini V, Werner S, Paganelli R (2009). "Pathogenesis of tendinopathies: inflammation or degeneration?". Arthritis Research & Therapy. 11 (3): 235. doi:10.1186/ar2723. PMC 2714139. PMID 19591655.

- ↑ du Toit, C; Stieler, M; Saunders, R; Bisset, L; Vicenzino, B (2008). "Diagnostic accuracy of power Doppler ultrasound in patients with chronic tennis elbow". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (11): 572–576. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2007.043901. hdl:10072/22142. ISSN 0306-3674. PMID 18308874. S2CID 3274396.

- ↑ Nirschl RP (October 1992). "Elbow tendinosis/tennis elbow". Clin Sports Med. 11 (4): 851–70. doi:10.1016/S0278-5919(20)30489-0. PMID 1423702.

- ↑ Maffulli N, Ewen SW, Waterston SW, Reaper J, Barrass V (2000). "Tenocytes from ruptured and tendinopathic achilles tendons produce greater quantities of type III collagen than tenocytes from normal achilles tendons. An in vitro model of human tendon healing". Am J Sports Med. 28 (4): 499–505. doi:10.1177/03635465000280040901. PMID 10921640. S2CID 13511471.

- ↑ Ho JO, Sawadkar P, Mudera V (2014). "A review on the use of cell therapy in the treatment of tendon disease and injuries". J Tissue Eng. 5: 2041731414549678. doi:10.1177/2041731414549678. PMC 4221986. PMID 25383170.

- ↑ McShane JM, Nazarian LN, Harwood MI (October 2006). "Sonographically guided percutaneous needle tenotomy for treatment of common extensor tendinosis in the elbow". J Ultrasound Med. 25 (10): 1281–9. doi:10.7863/jum.2006.25.10.1281. PMID 16998100. S2CID 22963436.

- ↑ Zeisig, Eva; Öhberg, Lars; Alfredson, Håkan (2006). "Sclerosing polidocanol injections in chronic painful tennis elbow-promising results in a pilot study". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 14 (11): 1218–1224. doi:10.1007/s00167-006-0156-0. ISSN 0942-2056. PMID 16960741. S2CID 23469092.

- ↑ Pingel J, Lu Y, Starborg T, Fredberg U, Langberg H, Nedergaard A, et al. (2014). "3-D ultrastructure and collagen composition of healthy and overloaded human tendon: evidence of tenocyte and matrix buckling". J Anat. 224 (5): 548–55. doi:10.1111/joa.12164. PMC 3981497. PMID 24571576.

- ↑ Duenwald S, Kobayashi H, Frisch K, Lakes R, Vanderby R (February 2011). "Ultrasound echo is related to stress and strain in tendon". J Biomech. 44 (3): 424–9. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.09.033. PMC 3022962. PMID 21030024.

- ↑ Duenwald-Kuehl S, Lakes R, Vanderby R (June 2012). "Strain-induced damage reduces echo intensity changes in tendon during loading". J Biomech. 45 (9): 1607–11. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.04.004. PMC 3358489. PMID 22542220.

- ↑ Tumilty S, Munn J, McDonough S, Hurley DA, Basford JR, Baxter GD (February 2010). "Low level laser treatment of tendinopathy: a systematic review with meta-analysis". Photomedicine and Laser Surgery. 28 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1089/pho.2008.2470. PMID 19708800. S2CID 10634480.

- ↑ Loew, Laurianne M; Brosseau, Lucie; Tugwell, Peter; Wells, George A; Welch, Vivian; Shea, Beverley; Poitras, Stephane; De Angelis, Gino; Rahman, Prinon (2014-11-08). "Deep transverse friction massage for treating lateral elbow or lateral knee tendinitis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (11): CD003528. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003528.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7154576. PMID 25380079.

- ↑ Gaujoux-Viala C, Dougados M, Gossec L (December 2009). "Efficacy and safety of steroid injections for shoulder and elbow tendonitis: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 68 (12): 1843–9. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.099572. PMC 2770107. PMID 19054817.

- ↑ Mohamadi, A; Chan, JJ; Claessen, FM; Ring, D; Chen, NC (January 2017). "Corticosteroid Injections Give Small and Transient Pain Relief in Rotator Cuff Tendinosis: A Meta-analysis". Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 475 (1): 232–243. doi:10.1007/s11999-016-5002-1. PMC 5174041. PMID 27469590.

- ↑ Dean, BJ; Lostis, E; Oakley, T; Rombach, I; Morrey, ME; Carr, AJ (February 2014). "The risks and benefits of glucocorticoid treatment for tendinopathy: a systematic review of the effects of local glucocorticoid on tendon". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 43 (4): 570–6. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.08.006. PMID 24074644.

- ↑ Kearney, RS; Parsons, N; Metcalfe, D; Costa, ML (26 May 2015). "Injection therapies for Achilles tendinopathy" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD010960. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010960.pub2. PMID 26009861.

- ↑ Moraes, Vinícius Y; Lenza, Mário; Tamaoki, Marcel Jun; Faloppa, Flávio; Belloti, João Carlos (2014-04-29). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 (4): CD010071. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd010071.pub3. PMC 6464921. PMID 24782334.

- ↑ McCormick A, Charlton J, Fleming D (Jun 1995). "Assessing health needs in primary care. Morbidity study from general practice provides another source of information". BMJ. 310 (6993): 1534. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6993.1534d. PMC 2549904. PMID 7787617.

- ↑ de Jonge S, et al. (2011). "Incidence of midportion Achilles tendinopathy in the general population". Br J Sports Med. 45 (13): 1026–8. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2011-090342. hdl:1765/30870. PMID 21926076. S2CID 206879020.

- ↑ Leppilahti J, Puranen J, Orava S. Incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:277-9

- ↑ Littlewood, Chris; May, Stephen; Walters, Stephen (2013-10-01). "Epidemiology of rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review". Shoulder & Elbow. 5 (4): 256–265. doi:10.1111/sae.12028. ISSN 1758-5740. S2CID 74208378.

- ↑ "Inflammation". The Free Dictionary.

- ↑ "avascular". The Free Dictionary.

- ↑ Rees, J. D.; Stride, M.; Scott, A. (2013). "Tendons - time to revisit inflammation". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 48 (21): 1553–1557. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091957. ISSN 0306-3674. PMC 4215290. PMID 23476034.

- ↑ Bass, Lmt (2012). "Tendinopathy: Why the Difference Between Tendinitis and Tendinosis Matters". International Journal of Therapeutic Massage & Bodywork: Research, Education, & Practice. 5 (1): 14–7. doi:10.3822/ijtmb.v5i1.153. PMC 3312643. PMID 22553479.

- ↑ D'Agostino MA, Olivieri I (June 2006). "Enthesitis". Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. Clinical Rheumatology. 20 (3): 473–86. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2006.03.007. PMID 16777577.

- ↑ "Enthesitis". Enthesitis. The Free Dictionary. 2009. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ↑ Schett, G; Lories, RJ; D'Agostino, MA; Elewaut, D; Kirkham, B; Soriano, ER; McGonagle, D (November 2017). "Enthesitis: from pathophysiology to treatment". Nature Reviews Rheumatology (Review). 13 (12): 731–741. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2017.188. PMID 29158573. S2CID 24724763.

- ↑ Schmitt, SK (June 2017). "Reactive Arthritis". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America (Review). 31 (2): 265–277. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2017.01.002. PMID 28292540.

- ↑ "OrthoKids - Osgood-Schlatter's Disease".

- ↑ "Sever's Disease". Kidshealth.org. Retrieved 2014-04-29.

- ↑ Hendrix CL (2005). "Calcaneal apophysitis (Sever disease)". Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery. 22 (1): 55–62, vi. doi:10.1016/j.cpm.2004.08.011. PMID 15555843.

- ↑ Murrell GA (2007). "Using nitric oxide to treat tendinopathy". Br J Sports Med. 41 (4): 227–31. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.034447. PMC 2658939. PMID 17289859.

- ↑ Rowe V, Hemmings S, Barton C, Malliaras P, Maffulli N, Morrissey D (November 2012). "Conservative management of midportion Achilles tendinopathy: a mixed methods study, integrating systematic review and clinical reasoning". Sports Med. 42 (11): 941–67. doi:10.2165/11635410-000000000-00000. PMID 23006143.

- ↑ Koch TG, Berg LC, Betts DH (2009). "Current and future regenerative medicine - principles, concepts, and therapeutic use of stem cell therapy and tissue engineering in equine medicine". Can Vet J. 50 (2): 155–65. PMC 2629419. PMID 19412395.

External links

- Questions and Answers about Bursitis and Tendinitis - US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases