The Great Goddess of Teotihuacan (or Teotihuacan Spider Woman) is a proposed goddess of the pre-Columbian Teotihuacan civilization (ca. 100 BCE - 700 CE), in what is now Mexico.

Discovery and interpretation

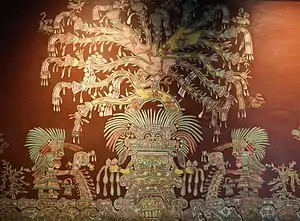

In years leading up to 1942, a series of murals were found in the Tepantitla compound in Teotihuacan. The Tepantitla compound provided housing for what appears to have been high status citizens and its walls (as well as much of Teotihuacan) are adorned with brightly painted frescoes. The largest figures within the murals depicted complex and ornate deities or supernaturals. In 1942, archaeologist Alfonso Caso identified these central figures as a Teotihuacan equivalent of Tlaloc, the Mesoamerican god of rain and warfare. This was the consensus view for some 30 years.

In 1974, Peter Furst suggested that the murals instead showed a feminine deity, an interpretation echoed by researcher Esther Pasztory. Their analysis of the murals was based on a number of factors including the gender of accompanying figures, the green bird in the headdress, and the spiders seen above the figure.[1] Pasztory concluded that the figures represented a vegetation and fertility goddess that was a predecessor of the much later Aztec goddess Xochiquetzal. In 1983, Karl Taube termed this goddess the "Teotihuacan Spider Woman". The more neutral description of this deity as the "Great Goddess" has since gained currency.

The Great Goddess has since been identified at Teotihuacan locations other than Tepantitla – including the Tetitla compound (see photo below), the Palace of the Jaguars, and the Temple of Agriculture – as well as on portable art including vessels[2] and even on the back of a pyrite mirror.[3] The 3-metre-high blocky statue (see photo below) which formerly sat near the base of the Pyramid of Moon is thought to represent the Great Goddess,[4] despite the absence of the bird-headdress or the fanged nosepiece.[5]

Esther Pasztory speculates that the Great Goddess, as a distant and ambivalent mother figure, was able to provide a uniting structure for Teotihuacan that transcended divisions within the city.[6]

After Teotihuacan

The Great Goddess is apparently peculiar to Teotihuacan, and does not appear outside the city except where Teotihuacanos settled.[7] There is very little trace of the Great Goddess in the Valley of Mexico's later Toltec culture, although an earth goddess image has been identified on Stela 1, from Xochicalco, a Toltec contemporary.[8] While the Aztec goddess Chalchiuhtlicue has been identified as a successor to the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan, archaeologist Janet Catherine Berlo has suggested that at least the Goddess' warlike aspect was assumed by the Aztec's protector god – and war god – Huītzilōpōchtli. The wresting of this aspect from the Great Goddess was memorialized in the myth Huitzilopochtli, who slew his sister Coyolxauhqui shortly after his birth.[9]

Berlo also sees echoes of the Great Goddess in the veneration of the Virgin of Guadalupe.[8]

The Great Goddess

Defining characteristics of the Great Goddess are a bird headress and a nose pendant with descending fangs.[10] In the Tepantitla and Tetitla murals, for example, the Great Goddess wears a frame headdress that includes the face of a green bird, generally identified as an owl or quetzal,[11] and a rectangular nosepiece adorned with three circles below which hang three or five fangs. The outer fangs curl away from the center, while the middle fang points down. She is also always seen with jewelry such as beaded necklaces and earrings which were commonly worn by Teotihuacan women. Her face is always shown frontally, either masked or partially covered, and her hands in murals are always depicted stretched out giving water, seeds, and jade treasures.[12]

Other defining characteristics include the colors red and yellow;[13] note that the Goddess appears with a yellowish cast in both murals.

In the depiction from the Tepantitla compound, the Great Goddess appears with vegetation growing out of her head, perhaps hallucinogenic morning glory vines[14] or the world tree.[15] Spiders and butterflies appear on the vegetation and water drips from its branches and flows from the hands of the Great Goddess. Water also flows from her lower body. These many representations of water led Caso to declare this to be a representation of the rain god, Tlaloc.

Below this depiction, separated from it by two interwoven serpents and a talud-tablero, is a scene showing dozens of small human figures, usually wearing only a loincloth and often showing a speech scroll (see photo below). Several of these figures are swimming in the criss-crossed rivers flowing from a mountain at the bottom of the scene. Caso interpreted this scene as the afterlife realm of Tlaloc, although this interpretation has also been challenged, most recently by María Teresa Uriarte, who provides a more commonplace interpretation: that "this mural represents Teotihuacan as [the] prototypical civilized city associated with the beginning of time and the calendar".[16]

.jpg.webp)

Domain

The Great Goddess is thought to have been a goddess of the underworld, darkness, the earth, water, war, and possibly even creation itself. To the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica, the jaguar, the owl, and especially the spider were considered creatures of darkness, often found in caves and during the night. The fact that the Great Goddess is frequently depicted with all of these creatures further supports the idea of her underworld connections.

In many murals, the Great Goddess is shown with many of the scurrying arachnids in the background, on her clothing, or hanging from her arms. She is often seen with shields decorated with spider webs, further suggesting her relationship with warfare. The Great Goddess is often shown in paradisial settings, giving gifts.[17] For example, the mural from Tepantitla shows water dripping from her hands while in the tableau under her portrait mortals swim, play ball, and dance (see photo to right). This seeming gentleness is in contrast to later similar Aztec deities such as Cihuacoatl, who frequently has a warlike aspect.[18] This contrast, according to Esther Pasztory, an archaeologist who has long studied Teotihuacan, extends beyond the goddesses in question to the core of the Teotihuacan and Aztec cultures themselves: "Although I cannot prove this precisely, I sense that the Aztec goal was military glory and staving off the collapse of the universe, whereas the Teotihuacan aim seems to have been the creation of paradise on earth."[19]

This is not to say, however, that the Great Goddess does not have her more violent aspect: one mural fragment, likely from Techinantitla, shows her as a large mouth with teeth, framed by clawed hands.[20]

Other interpretations

Mixed-Gender Interpretation

Elisa C. Mandell's 2015 article "A New Analysis of the Gender Attribution of the 'Great Goddess' of Teotihuacan"[21] published by Cambridge challenges the interpretation of the Great Goddess as being not only female but also male, a mixed-gender figure. Sex is understood as the biological and anatomical difference between men and women, while gender is a socially and culturally constructed identity. There are disagreements among historians over the role of biology to informing gender and “whether sex as a biological concept exists outside Western society”.[22] There is a history of mixed-gender identity within Mesoamerican people, and considering that the Goddess is from Teotihuacan, Western models of gender binary should not be imposed upon non-Western figures. Additionally, there are no explicit sexual characteristics shown on the Great Goddess so their sex cannot be deduced.[21]

There is a history of masculine and feminine attributes being shown within the same figure in Mesoamerican art. The Maya Maize Deity can be seen as an example of this, as posited by Bassie-Sweet. Considering the importance of maize, or corn, which has the ability to switch between the two biological sexes. With the fact that Mesoamerican people considered themselves to be descendants of the corn plant, this nature based culture allows for ambiguity of sex and gender within the peoples.[23] Furthermore, we have evidence that the Maize God inspired Maya elites, no matter their gender, to wear mixed-gender costumes to honor the Maize God.[24]

Mandell's article analyzes and reattributes each element included in the Goddesses depiction in the Tepantitla and Tetitla murals, reconsidering previous gendering of these elements. Pasztory references the three main elements of the Goddess: the avian headdress, the yellow and red zig-zags, and the nosebar.[25] Mandell references many depictions of male and female deities where these elements are including, suggesting that it is impossible to determine any specific gendering from the headdress, zig-zags, and nosebar. Mandell then suggests that the mixture of these male and female attributes suggests that the Goddess is mixed-gender.

More generally, many images have been understood as depicting the Goddess because of their inclusion of water, which is also understood as a feminine symbol. Mandell posits that there is nothing inherently feminine about this liquid.[21] In the Tepantitla and Tetitla murals, the water is filled with seed and shell shaped object. Liquid with sea-life and sperm may represent semen made up of sperm, thus suggesting a masculine association. One of the reasons Pasztory had asserted that the Goddess was a feminine deity is because it was understood to be wearing a quechquemitl.[25] The quechquemitl is often associated with female figures. However, the triangular shirt or cape had multiple meanings for different people that also changed over time,[26] and therefore it cannot be used as a simple demarcation of a figure’s sex or gender. Similarly, the Goddess’ ear ornaments had been a factor in deciphering the deity as feminine. Mandell asserts that there is no conclusive evidence to support these ornaments as feminine, and rather this particular ear ornament has been seen on male and female gods. The short skirt seen worn by figures in the Tepantitla mural has been considered another attribute of femininity, yet in Teotihuacan it was more common for males to be depicted in short kilts.[27] The profile figures in the Tepantitla mural carry small bags, which men are known to carry, as seen in depictions of priests in Maya art. Mandell asserts that the ambiguity and combination of masculine and feminine attributes should be seen as a mixed-gender performance, not subjected to the Western binary model of gender.[21]

Various Interpretations within the Archaeological Community

- In a 2006 article in Ancient Mesoamerica, Zoltán Paulinyi argues that the Great Goddess or Spider Woman is "highly speculative" and is a result of fusing up to six unrelated gods and goddesses.

- In "The Olmec Mountain and Tree Creation in Mesoamerican Cosmology", Linda Schele states that the primary mural represents "either a Teotihuacan ruler or the Great Goddess".[28]

- In her 2007 book, The Teotihuacan Trinity, Anna Headrick is cautious in identifying the murals as portraits of the Great Goddess, preferring the term "mountain-tree". Headrick identifies the tree which sprouts from the headdress as the Mesoamerican world tree.[29]

Similar deities

Some American Indians, such as the Pueblo and Navajo, revered what seems to be a similar deity. Referred to as the Spider Grandmother, she shares many traits with the Teotihuacan Spider Woman.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Pasztory (1977), pp. 83–85.

- ↑ Pasztory (1977), pp.87–91.

- ↑ Berlo (1992), p. 145. This mirror back is presently in the Cleveland Museum of Art and can be seen here.

- ↑ Headrick (2002). Berlo (1992), p. 137.

- ↑ The absence of the bird-headdress and the fanged nosepiece is noted in Cowgill (1997), p. 149.

- ↑ Pasztory (1993), p. 61-62.

- ↑ Pasztory (1993), p. 56-57.

- 1 2 Berlo, p. 154.

- ↑ Berlo, p. 152.

- ↑ Cowgill, p. 149. Headrick (2007), p. 33.

- ↑ Pasztory (1977), p.87.

- ↑ Million, Rene (1993). Berrin, Kathleen.; Pasztory, ., Esther. (eds.). Teotihuacan : art from the city of the gods. New York,New York: Thames and Hudson. p. 55. ISBN 978-0500277676.

- ↑ Berlo, p. 140.

- ↑ Furst (1974).

- ↑ Headrick (2002), p. 86. Headrick (2007). See also course notes by Kappelman (2002). Note, however, that there appear to be two separate and differently colored trees, one with spiders and one with butterflies.

- ↑ Uriarte (2006, abstract). Note that Uriarte's description gibes with Pasztory's assessment of a Teotihuacan culture dedicated to the creation of paradise on earth.

- ↑ Pasztory (1993), p. 61.

- ↑ Miller & Taube, p. 61.

- ↑ Pasztory (1993), p. 49.

- ↑ Berrin & Pasztory, p. 195.

- 1 2 3 4 Mandell, Elisa (2015). "A NEW ANALYSIS OF THE GENDER ATTRIBUTION OF THE "GREAT GODDESS" OF TEOTIHUACAN". www-cambridge-org.lp.hscl.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

- ↑ Ardren, Traci (2008-03-01). "Studies of Gender in the Prehispanic Americas". Journal of Archaeological Research. 16 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1007/s10814-007-9016-9. ISSN 1059-0161. S2CID 144613579.

- ↑ Bassie-Sweet, Karen 2002 Corn Deities and the Male/Female Principle. In Ancient Maya Gender Identity and Relations, edited by Gustafson, Lowell S.and Trevelyan, Amelia M., pp. 169–190. Bergin and Garvey, Westport, CT.

- ↑ F. Kent Reilly 2002 Female and Male: The Ideology of Balance and Renewal in Elite Costuming Among the Classic Period Maya. In Ancient Maya Gender Identity and Relations, edited by Lowell S.Gustafson and Amelia M.Trevelyan, pp. 319–328. Bergin and Garvey, Westport, CT.

- 1 2 Esther Pasztory 1992b Abstraction and the Rise of a Utopian State at Teotihuacan. In Art, Ideology, and the City of Teotihuacan, edited by Janet C.Berlo, pp. 281–320. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, DC.

- ↑ McCafferty, Sharisse D.; McCafferty, Geoffrey G. (Fall 1994). "The Conquered Women of Cacaxtla: Gender identity or gender ideology?". Ancient Mesoamerica. 5 (2): 159–172. doi:10.1017/S0956536100001127. ISSN 1469-1787. S2CID 161794332.

- ↑ Scott, Sue (2001). The Corpus of terracotta figurines from Sigvald Linné's excavations at Teotihuacan, Mexico (1932 & 1934-35) and comparative material. Stockholm, Sweden: National Museum of Ethnography. ISBN 978-9185344406. OCLC 48115920.

- ↑ Schele (1996), p.111, fig. 20. See also this synopsis.

- ↑ Headrick (2007), p. 141.

- ↑ Headrick, Annabeth (2002), p. 86. Headrick (2007), p. 33.

References

- Berlo, Janet Catherine (1992) "The Great Goddess Reconsidered", in Art, Ideology, and the City of Teotihuacan", Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C.

- Cowgill, George (1997). "State and Society at Teotihuacan, Mexico" (PDF online reproduction). Annual Review of Anthropology. 26 (1): 129–161. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.129. OCLC 202300854.

- Furst, Peter (1974). "Morning Glory and Mother Goddess at Tepantitla, Teotihuacan: Iconography and Analogy in Pre-Columbian Art". In Norman Hammond (ed.). Mesoamerican Archaeology: New Approaches. proceedings of a Symposium on Mesoamerican Archaeology held by the University of Cambridge Centre of Latin American Studies, August 1972. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 187–215. ISBN 978-0-292-75008-1. OCLC 1078818.

- Headrick, Annabeth (2002) "The Great Goddess at Teotihuacan" in Andrea Stone Heart of Creation: the Mesoamerican World and the Legacy of Linda Schele, University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, ISBN 0-8173-1138-6.

- Headrick, Annabeth (2007). The Teotihuacan Trinity: The Sociopolitical Structure of an Ancient Mesoamerican City. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71665-0.

- Kappelman, Julia G. (2002). "Mesoamerican Art - Teotihuacan". Precolumbian Art and Art History. Department of Art & Art History, University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original (ART347L course syllabus and notes) on 2007-12-09. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya: An Illustrated Dictionary of Mesoamerican Religion. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05068-2. OCLC 27667317.

- Pasztory, Esther (1971). The Murals of Tepantitla, Teotihuacan (PhD thesis). Columbia University.

- Pasztory, Esther (1977). "The Gods of Teotihuacan: A Synthetic Approach in Teotihuacan Iconography". In Alana Cordy-Collins; Jean Stern (eds.). Pre-Columbian Art History: Selected Readings. Palo Alto, CA: Peek Publications. pp. 81–95. ISBN 978-0-917962-41-7. OCLC 3843930..

- Pasztory, Esther (1993). "Teotihuacan Unmasked". In Berrin, Kathleen and Esther Pasztory (ed.). Teotihuacan: Art from the City of the Gods. New York: Thames and Hudson. pp. 44–63.

- Paulinyi, Zoltán (2006). "The "Great Goddess" of Teotihuacan: Fiction or Reality?". Ancient Mesoamerica. 17 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1017/S0956536106060020. ISSN 0956-5361. OCLC 21544811. S2CID 163124002.

- Schele, Linda (1996). "The Olmec Mountain and Tree Creation in Mesoamerican Cosmology". The Olmec World: Ritual and Rulership (Cloth ed.). Princeton, NJ: The Art Museum, Princeton University in association with Harry N. Abrams (New York). pp. 105–119. ISBN 978-0-8109-6311-5. OCLC 34103154. Catalog of an exhibition held Dec. 16, 1995—Feb. 25, 1996 at the Art Museum, Princeton University, and Apr. 14—June 9, 1996 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

- Taube, Karl (1983). "The Teotihuacan Spider Woman". Journal of Latin American Lore. 9 (2): 107–189. ISSN 0360-1927. OCLC 1845716.

- Uriarte, Maria Teresa (2006). "The Teotihuacan Ballgame and the Beginning of Time". Ancient Mesoamerica. 17 (1): 17–38. doi:10.1017/S0956536106060032. ISSN 0956-5361. OCLC 88827568. S2CID 162613065.