Texarkana, Arkansas | |

|---|---|

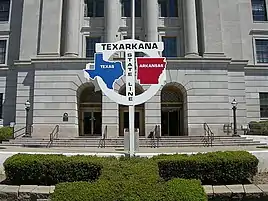

From top, left to right: Downtown, Augustus M. Garrison House, Texarkana City Hall, Texarkana state line | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The Arkansas Side, TXK | |

| Motto: "Twice as Nice" | |

Location in Miller County, Arkansas | |

Texarkana Location within Arkansas  Texarkana Location within the United States  Texarkana Texarkana (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 33°25′59″N 94°1′14″W / 33.43306°N 94.02056°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arkansas |

| County | Miller |

| Incorporated | August 10, 1880 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Allen L. Brown |

| • Board of Directors | Directors

|

| • City Manager | Robert Thompson |

| Area | |

| • Total | 42.21 sq mi (109.31 km2) |

| • Land | 41.98 sq mi (108.72 km2) |

| • Water | 0.23 sq mi (0.59 km2) |

| Elevation | 361 ft (110 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 29,387 |

| • Density | 700.06/sq mi (270.30/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 71854 |

| Area code | 870 |

| FIPS code | 05-68810 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0078542 |

| Website | cityoftexarkanaar |

Texarkana is a city in the U.S. state of Arkansas and the county seat of Miller County, on the southwest border of the state. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 29,387.[2] The city is located across the state line from its twin city of Texarkana, Texas. The city was founded at a railroad intersection on December 8, 1873, and was incorporated in Arkansas on August 10, 1880. Texarkana and its Texas counterpart are the principal cities of the Texarkana metropolitan area, which in 2021 was ranked 289th in the United States with a population of 147,174, according to the United States Census Bureau.

Within the Ark-La-Tex subregion of southwest Arkansas, Texarkana is located in the Piney Woods, an oak–hickory forest that dominates the flat Gulf Coastal Plain. Texarkana's economy is based on agriculture. The city has long been a trading center, first located at the intersection of major railroads serving Texas, Arkansas and north into Missouri. Since then three major Interstate highways constructed crossroads here: Interstate 30 (I-30), I-49, and the future I-69. Outdoor tourism, such as fishing at Lake Millwood and related activities, is important economically in the region. The Red River Army Depot & Tenants comprise the largest single employer in the city.

The Texarkana Arkansas School District is the largest public school district on the Arkansas side. The city has a branch campus of the University of Arkansas Community College at Hope (UACCH). On the Texas side is located Texarkana College.

History

Miller County was formed in 1820 in the Arkansas Territory; it was named in honor of James Miller, Arkansas' first territorial governor and a general during the War of 1812. Much of its eastern border is formed by the Red River. At the time, there was considerable uncertainty among Americans as to the location of the boundary between the county (and the United States) and national territory of Mexico, which then included Texas.

Consequently, settlers believed that Arkansas levied and collected taxes on land that eventually might be held by Mexico. Moreover, many who resented what they considered Mexican oppression of European-American Texans were openly declaring allegiance to the Texans.

After the Texas Republic gained independence from Mexico, regional unrest increased. In 1838, Governor James Conway proposed that the "easiest and most effective remedy is the abolition of Miller County to an area which is more patriotic." Miller County was dissolved and its land was made part of Lafayette County, Arkansas.

In 1873 town lots were sold in Texarkana, Arkansas, at the intersection of two railroads, which stimulated its growth as a trading center. In this area and time period, railroads had replaced rivers as the preferred method of transportation and shipping, and new towns were sited for best advantage via the railroad. The next year (1874), Texarkana, Texas, was founded on the rail line on June 12 across the state border.

That same year, the Arkansas legislature re-established Miller County.[3] Efforts of the young town in Arkansas to be incorporated were not realized until October 17, 1880, nearly seven years after Texarkana, Texas, was formed. Both Texarkana cities generally recognize December 8, 1873, as the date of organization.[3]

On February 11, 1922, masked men lynched Mr. Norman, an African-American man, in Texarkana, Miller County, Arkansas. Lynchings were perpetrated by white men primarily against black males, although some black women were also lynched in the South.

Geography

Texarkana, Arkansas, is located at 33°25′59″N 94°1′14″W / 33.43306°N 94.02056°W (33.433075, -94.020514).[4] It is 143 miles (230 km) southwest of Little Rock, 72 miles (116 km) north of Shreveport, Louisiana, and 180 miles (290 km) northeast of Dallas, Texas. According to the United States Census Bureau, Texarkana has a total area of 42.2 square miles (109 km2), of which 42.0 square miles (109 km2) are land and 0.2 square miles (0.5 km2), or 0.54%, are water.[1] The city is mainly drained by Nix Creek, a southwest-flowing tributary of Days Creek, part of the Sulphur River watershed leading to the Red River.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Texarkana has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[5]

| Climate data for Texarkana, Arkansas (Webb Field), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1892–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 85 (29) |

89 (32) |

94 (34) |

95 (35) |

100 (38) |

108 (42) |

110 (43) |

117 (47) |

108 (42) |

104 (40) |

89 (32) |

84 (29) |

117 (47) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 73.8 (23.2) |

76.2 (24.6) |

83.0 (28.3) |

86.4 (30.2) |

91.3 (32.9) |

95.9 (35.5) |

100.1 (37.8) |

100.7 (38.2) |

96.7 (35.9) |

90.1 (32.3) |

80.1 (26.7) |

74.8 (23.8) |

102.4 (39.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 54.0 (12.2) |

58.2 (14.6) |

66.7 (19.3) |

74.5 (23.6) |

81.6 (27.6) |

88.7 (31.5) |

92.7 (33.7) |

92.8 (33.8) |

86.4 (30.2) |

76.0 (24.4) |

64.3 (17.9) |

55.7 (13.2) |

74.3 (23.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.6 (7.0) |

48.3 (9.1) |

56.0 (13.3) |

63.6 (17.6) |

71.6 (22.0) |

78.9 (26.1) |

82.5 (28.1) |

82.0 (27.8) |

75.4 (24.1) |

64.9 (18.3) |

53.9 (12.2) |

46.4 (8.0) |

64.0 (17.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 35.1 (1.7) |

38.4 (3.6) |

45.2 (7.3) |

52.7 (11.5) |

61.6 (16.4) |

69.1 (20.6) |

72.3 (22.4) |

71.3 (21.8) |

64.5 (18.1) |

53.7 (12.1) |

43.6 (6.4) |

37.2 (2.9) |

53.7 (12.1) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 19.0 (−7.2) |

24.6 (−4.1) |

29.7 (−1.3) |

37.2 (2.9) |

48.2 (9.0) |

60.4 (15.8) |

65.4 (18.6) |

64.5 (18.1) |

52.0 (11.1) |

38.5 (3.6) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

22.9 (−5.1) |

16.8 (−8.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −7 (−22) |

−9 (−23) |

11 (−12) |

24 (−4) |

35 (2) |

50 (10) |

56 (13) |

51 (11) |

37 (3) |

21 (−6) |

15 (−9) |

−1 (−18) |

−9 (−23) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.64 (92) |

4.28 (109) |

4.45 (113) |

4.43 (113) |

5.10 (130) |

3.92 (100) |

3.37 (86) |

2.98 (76) |

3.60 (91) |

4.51 (115) |

3.91 (99) |

4.68 (119) |

48.87 (1,241) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.6 (4.1) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.9 (2.3) |

2.7 (6.91) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.2 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 8.9 | 9.8 | 8.2 | 6.7 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 7.2 | 8.7 | 9.3 | 99.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.2 |

| Source: NOAA (snow/snow days 1981–2010)[6][7][8] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 1,390 | — | |

| 1890 | 3,528 | 153.8% | |

| 1900 | 4,914 | 39.3% | |

| 1910 | 5,655 | 15.1% | |

| 1920 | 8,257 | 46.0% | |

| 1930 | 10,764 | 30.4% | |

| 1940 | 11,821 | 9.8% | |

| 1950 | 15,875 | 34.3% | |

| 1960 | 19,788 | 24.6% | |

| 1970 | 21,682 | 9.6% | |

| 1980 | 21,459 | −1.0% | |

| 1990 | 22,631 | 5.5% | |

| 2000 | 26,448 | 16.9% | |

| 2010 | 29,919 | 13.1% | |

| 2020 | 29,387 | −1.8% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[9] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 16,113 | 54.83% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 10,347 | 35.21% |

| Native American | 158 | 0.54% |

| Asian | 175 | 0.6% |

| Pacific Islander | 2 | 0.01% |

| Other/Mixed | 1,348 | 4.59% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,244 | 4.23% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 29,387 people, 11,404 households, and 7,348 families residing in the city.

2016

As of the census[11] of 2016, there were 30,283 people, 13,565 households, and 7,040 families residing in the city. The population density was 830.5 inhabitants per square mile (320.7/km2). There were 11,721 housing units at an average density of 368.1 per square mile (142.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 65.93% White, 31.00% Black or African American, 0.48% Native American, 0.50% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.61% from other races, and 1.46% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.78% of the population.

There were 13,565 households, out of which 32.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.3% were married couples living together, 18.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.2% were non-families. 28.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 2.99.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 25.9% under the age of 18, 10.1% from 18 to 24, 28.5% from 25 to 44, 21.5% from 45 to 64, and 14.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 87.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,343, and the median income for a family was $38,292 . Males had a median income of $35,204 versus $21,731 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,130. About 17.2% of families and 21.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 33.0% of those under age 18 and 15.7% of those age 65 or above.

Government and infrastructure

The Arkansas Department of Correction operates the Texarkana Regional Correction Center in Texarkana.[12]

Arkansas residents whose permanent residence is within the city limits of Texarkana, Arkansas, are exempt from Arkansas individual income taxes.[13]

The Federal Courthouse (which holds the city's only post office) is located directly on the Arkansas-Texas state line. It is the only federal office building to straddle a state line.

According to the city's 2018 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[5] the top employers in the area are:

- Red River Army Depot & Tenants 4,135,

- Christus St. Michael Health Care 1,800,

- Cooper Tire & Rubber Company 1,750,

- AECOM/URS 1,300,

- Southern Refrigerated Transport 1,235,

- Wal-Mart 1,200,

- Texarkana TX Independent School District 1,150,

- Domtar, Inc. 900,

- Graphic Packaging 800,

- Wadley Regional Medical Center 755,

- Texarkana Arkansas School District 785,

Transportation

Education

Public education for elementary and secondary school students is provided by two school districts:

- Texarkana Arkansas School District, which leads to graduating from Arkansas High School. The high school mascot is the Razorback. The University of Arkansas selected this mascot in exchange for giving the school some used athletic equipment. This practice no longer occurs.[14]

- A very small portion of the city is within the Genoa Central School District,[15] which leads to graduation from Genoa Central High School. The high school mascot is the Dragon; green and white serve as the school colors.

Private education opportunities include:

- Trinity Christian School, a Baptist school serving pre-kindergarten through grade 12.

In 2012, a branch of the University of Arkansas Community College at Hope was established at Texarkana. It is known as University of Arkansas Hope-Texarkana (UAHT). In 2015 UAHT began partnering with the University of Arkansas Little Rock, to offer bachelor's degree programs through UALR Texarkana, with classes held on the UAHT Texarkana campus.[16]

Pop culture

- Clutch's 2001 song "Immortal" refers to the city with the lyric, "Who found the ark inside Texarkana?"

- Texarkana is referenced in the song "Cotton Fields" by the American folk and blues musician Lead Belly. This was later covered by several notable country and rock artists, including The Highwaymen, Buck Owens, The Beach Boys, Elton John, and Creedence Clearwater Revival. Lead Belly (Huddie Ledbetter) was born on a cotton plantation near Linden, Texas, about 40 miles (64 km) southwest of Texarkana. He later worked on a plantation near De Kalb, Texas, about 35 miles (56 km) west of Texarkana.

- Brenda Lee's 1959 song "Let's Jump the Broomstick" refers to the city with the lyric, "Goin' to Alabama back from Texarkana, Goin' all around the world".

- Texarkana is one of the places visited by the red car in The Brave Little Toaster during the song "Worthless".

- Tesla's 1991 song "Call It What You Want" contains the lyric, "All I am is all I'll ever be, and that's just a boy from Texarkana." Jeff Keith, the lead singer of the band, is from Texarkana.

- "Texarkana" is a 1991 song by R.E.M. The track appears on the band's seventh studio album, Out of Time.

- In the 1977 movie Smokey and the Bandit, The Bandit (Burt Reynolds and the Snowman Jerry Reed) are making a run from Atlanta to Texarkana to get a load of beer; afterward, Sheriff Buford T. Justice (Jackie Gleason) and his son of Texarkana, Texas, pursue them. Jerry Reed's 1977 hit song "East Bound and Down" from the soundtrack refers to the city in the lyric, "The boys are thirsty in Atlanta and there's beer in Texarkana," regarding the lack of availability of Coors beer east of Texas at that time. (In fact, Texarkana, Texas, was dry until 2014 - the alcohol distributor is actually in Texarkana, Arkansas.)

- In Season 5, Episode 5, "Southbound and Down" of the FX TV show Archer, Archer and the crew from ISIS encounter a hostile biker gang in Texarkana while on their way to Austin, Texas.

- In a 2013 episode of American Pickers on The History Channel, Frank and Mike visited several spots in Texarkana.

- In the movie Zombieland, Woody Harrelson refers to his relationship with companion Jesse Eisenberg that he figures it will last "all the way to Texarkana".

- This was the setting for the movie The Town That Dreaded Sundown (1976), which was loosely based on the Texarkana Moonlight Murders.

- In the novel A Canticle for Leibowitz, centuries after a nuclear war that reduces world civilization to a second dark age, Texarkana rises as the capital of a burgeoning empire that expands across the former United States and becomes known as the Atlantic Confederacy.

- The end scene of Sacha Baron Cohen's movie Brüno (2009) was filmed in Texarkana.

- In 2016, a video of a Texarkana minister defending LGBT rights in a speech went viral online.[17]

Notable people

- Buster Benton, blues singer-guitarist[18]

- Ben M. Bogard, founder in 1924 of the American Baptist Association; while living in Texarkana, Arkansas, in 1914 he founded The Baptist Commoner denominational newspaper, later in 1917 combined as The Baptist and Commoner[19]

- Mike Cherry, New York Giants football, Murray State quarterback[20]

- Willie Davis, player with Green Bay Packers in the NFL and Super Bowl champion

- Martin Delray, country music singer

- Wayne Dowd, Arkansas state senator and lawyer

- Wilhelm L. Friedell, U.S. Navy rear admiral, Navy Cross recipient, and submariner[21]

- Prissy Hickerson, former member of Arkansas Highway Commission for whom Loop 245 is named "Hickerson Highway"; current member of Arkansas House of Representatives from Miller County[22]

- Mike Huckabee, governor; pastored Beech Street First Baptist Church, 1986-1992[23]

- Parnelli Jones, 1963 Indianapolis 500 champion

- Scott Joplin, composer and pianist of ragtime music

- Jeff Keith, lead singer of rock band Tesla

- Dana Kimmell, actress

- A. Lynn Lowe, farmer and former Arkansas Republican Party state chairman and 1978 gubernatorial nominee against Bill Clinton

- Jimmy Means, NASCAR driver and owner[24]

- Bryce Mitchell, professional mixed martial artist competing in the UFC

- Dustin Moseley, Major League Baseball player with the San Diego Padres in the MLB

- Conlon Nancarrow, composer who specialized in works for the player piano

- Charles B. Pierce, director and movie producer of The Legend of Boggy Creek and The Town That Dreaded Sundown

- Don Rogers, football player with Cleveland Browns in the NFL

- Mike Ross, former congressman and 2014 Arkansas gubernatorial nominee

- Max Sandlin, former congressman from Texas, and husband of former congresswoman Stephanie Herseth Sandlin from South Dakota's at-large congressional district

- Rod Smith, football player with the Denver Broncos in the NFL; two-time Super Bowl Champion

- Jasper Taylor, early jazz drummer, recorded with Jelly Roll Morton, Freddy Keppard, many others

- Jerry Turner, former Major League Baseball outfielder

- Dennis Woodberry, player with Washington Redskins in the NFL and one-time Super Bowl champion

References

- 1 2 "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files: Arkansas". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- 1 2 "P1. Race – Texarkana city, Arkansas: 2020 DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- 1 2 "Texarkana Chamber of Commerce". Texarkana.org. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Texarkana, Arkansas Köppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ↑ "Station: Texarkana Webb FLD, AR". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ↑ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Texarkana Webb Field, AR (1981–2010)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Arkansas Department of Corrections". Adc.arkansas.gov. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ "State of Arkansas Department of Finance and Administration Texarkana Exemption Letter" (PDF). Dfa.arkansas.gov. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ↑ "History of Texarkana: Did You Know?". Texarkana Arkansas School District. Archived from the original on February 22, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ↑ "SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP (2010 CENSUS): Miller County, AR." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on October 15, 2017.

- ↑ "University of Arkansas at Little Rock". Ualr.edu. Archived from the original on June 8, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Facebook". Facebook. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ Bill Dahl. "Buster Benton | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ↑ "Benjamin Marcus Bogard (1868–1951)". encyclopediaofarkansas.net. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Mike Cherry, QB at". Nfl.com. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ "Wilhelm Lee Friedell". Military Times. Retrieved December 17, 2021.

- ↑ "Representative Prissy Hickerson's Political Summary". votesmart.org. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- ↑ Mike Huckabee, From Hope to Higher Ground, New York: Center Street Publishers, 2007, p. 5

- ↑ "Jimmy Means • Career & Character Info | Motorsport Database". Motorsport Database - Motor Sport Magazine. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

External links

- Official website

- Texarkana Business Reviews

- History of Texarkana's Jewish community (from the Institute of Southern Jewish Life)

- Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture entry: Texarkana (Miller County)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)