| The Adventures of Mark Twain | |

|---|---|

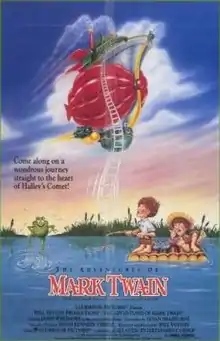

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Will Vinton |

| Screenplay by | Susan Shadburne[1] |

| Based on | The works of Mark Twain |

| Produced by | Will Vinton |

| Starring | James Whitmore |

| Cinematography | Bruce McKean |

| Edited by | Kelley Baker Michael Gall Will Vinton |

| Music by | Billy Scream |

Production companies | Will Vinton Productions Harbour Town Films |

| Distributed by | Clubhouse Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 86 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.5 million[3] |

| Box office | $849,915[4] |

The Adventures of Mark Twain, also known as Comet Quest in the United Kingdom, is a 1985 American independent[5] stop-motion claymation fantasy film directed by Will Vinton and starring James Whitmore. It received a limited theatrical release in May 1985 and was released on DVD in January 2006[6] and again as a collector's edition in 2012 on DVD and Blu-ray.

The film features a series of vignettes extracted from several of Mark Twain's works, woven together by a plot that follows Twain's attempts to keep his "appointment" with Halley's Comet. Twain and three children, Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn, and Becky Thatcher, travel on an airship to various adventures, encountering characters from Twain's stories along the way.[7]

Plot

Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer sneak aboard an airship piloted by Mark Twain in their dreams of becoming famous aeronauts. After a bout of one-upmanship, Becky Thatcher follows them to call their bluff. The balloon takes off and the stowaways are soon discovered, but they are surprised to learn that Twain already knows their names. Upon seeing the frog the boys had caught outside of town, Twain relates his first popular short story, "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County".

The boys learn that Twain intends to pilot the airship to meet Halley's Comet, and are worried that this goal will end in their deaths. They stumble upon the Index-o-Vator, a strange elevator that can take them to any part of the vessel, or into any of Twain's writing. Using it, they meet up with Twain and Becky, who is intrigued by a coin-operated automaton of Adam and Eve. Twain takes the chance to begin telling them the story of Adam and Eve, based on his stories Eve's Diary and Extracts from Adam's Diary. The story comes to a halt when a real storm surrounds the airship just as storm clouds fill the Garden of Eden. Twain quickly coaches the kids on how to pilot the ship, but they fail to avoid smashing into a mountain and losing a chunk of the hull.

Disheartened, the three head back to the Index-o-Vator, where the door opens to a scene from The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Huck and Becky are excited at the opportunity to return home, but Tom only cares about avoiding Aunt Betty's chores and changes the floor before the others can protest. Mark Twain emerges from the open void, now dressed in a black suit instead of his usual white one. He changes the floor again and encourages the kids to enter a scene from The Chronicles of Young Satan.

Tom explains his plan to Huck and Becky, and they conspire to sabotage Twain's suicidal voyage and take control of the airship. They lie low as Twain teaches them how to fly the vessel, and Tom senses an opportunity in the central power panel. They follow Twain into his office to tie him up when he falls asleep, but to their surprise, he greets them again on the deck. The kids ask if there is another life waiting for them after they collide with the comet, and Twain relates the story of Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven.

With their plan in place, the children wait anxiously as Twain continues the story of Adam and Eve, whose designs bear a striking resemblance to Mark Twain and his wife, Olivia. Twain says, "Wherever she was, there was Eden," and laments her death, wishing to see her again when he meets the comet. The children discover the true reason for Twain's journey: he believes he is destined to die with the return of the comet, and this journey is his way of accepting his fate and leaving the children behind unharmed. It is too late to stop him, however, and Tom's contraption goes off, destroying the main power and trapping them below decks. Huck's pet frog saves the day by leaping from the porthole and landing on the backup power button.

The crew sets off, with the children now expertly piloting the ship under Twain's command. They enter the comet and finally come face-to-face with the strange figure who has been haunting the ship: Twain's double. Twain explains that the double is his darker side, who is as much an important part of him as the lighthearted humorist the children are familiar with. The two give the children several pieces of advice, all real Mark Twain quotes, and muse on whether or not there is another life waiting for them. They merge and disappear into dust, leaving Twain's face to appear in the comet's clouds. When asked where he is going, he answers, "Back to Eden."

The airship is blown out of the comet by Twain, and the kids decide to write up their journey in a book called "The Adventures of Mark Twain by Huck Finn".

Cast

- James Whitmore as Mark Twain

- Michele Mariana as Becky Thatcher

- Gary Krug as Huck Finn

- Chris Ritchie as Tom Sawyer

- John Morrison as Adam

- Carol Edelman as Eve

- Dallas McKennon as Jim Smiley and Newspaper Boy

- Herb Smith as The Stranger

- Marley Stone as Aunt Polly

- Michele Mariana & Wilbur Vincent as The Mysterious Stranger

- Wally Newman as Captain Stormfield

- Tim Conner as Three-Headed Alien

- Todd Tolces as Saint Peter

- Billy Scream as The Indexivator

- Wilf Innton as Dan'l Webster

- Billy Victor as God

- Compton Downs as Injun Joe

- Gary Thompson as Baby Cain

Production

The concept was inspired by a famous quote by the author:

"I came in with Halley's Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year (1910), and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don't go out with Halley's Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: 'Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.'"[8]

Twain died on April 21, 1910, one day after Halley's Comet reached perihelion in 1910.[9]

Research into the life of Mark Twain was performed by Daniel and Mary Yost which in turn was adapted by Will Vinton's then wife, Susan Shadburne, into an original story.[10] The characters were designed and sculpted by Barry Bruce, and Gary McRobert developed a new computerized motion system to replace the old wooden hand-cranked method.[10] Vinton took black-and-white footage of actors during recording sessions for the animators to use as reference for timing and motion.[10] The film took three and-a-half years to complete.[10]

This animated film, which tested well with teens and college students before it was labeled with a G rating which hurt their box office chances, was shot in Portland, Oregon[11] and when he was asked about the rumors of this film being made by a 17-person crew,[3] Vinton stated:

Well it's all true, though that's probably exaggerating a bit. Seventeen or so represents the full-time staff and then freelance people came and went, plus you have musical talent and writing talent and things that go beyond that number. We shot the film in a converted house that had a barbershop in front of it, so we called it the Barbershop Studio. The bedrooms and things were editing rooms and offices. The high-ceiling basement was conveniently connected to a four thousand square foot studio that we built in the back, and that basement was where the animators and sculptors worked on the characters. So, yes, we spent a lot of time in the basement![3]

Release

Despite the film's successful showings to various adult audiences during test screenings, Atlantic Releasing chose to release the film as part of their children's matinee label, Clubhouse Pictures.[10] Producer Hugh Tirrell attempted to avoid this fate for the film by making a deal with Atlantic to do a test run of the film as a feature in his home town of Buffalo, New York for a week.[10] While Tirrell did what he could to promote the film including screening the film for Mark Twain scholars at the University at Buffalo as well as promoting the film on TV and Radio interviews, but without support from Atlantic who did little to distance the film from the Clubhouse label, the movie's feature run failed and the movie would play out as a matinee.[10]

Reception and legacy

On Rotten Tomatoes it has a score of 80% based on reviews from five critics, with an average rating of 8/10.[12]

On Common Sense Media it has 3/5 stars.[13]

Animation critic Charles Solomon listed it as one of the best animated films of the 1980s a year after the film's release and calling it Vinton's most mature work.[14][15]

See also

References

- ↑ "Movie Review - - SCREEN: 'ADVENTURES OF MARK TWAIN". The New York Times. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ↑ '"The Adventures of Mark Twain (1985)". tcm.com. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- 1 2 3 "Feat of Clay: The Forgotten 'Adventures of Mark Twain". Animation World Network. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ↑ The Adventures of Mark Twain at Box Office Mojo

- ↑ 3 Reasons Why: The Adventures of Mark Twain (1985)|Zippy Frames

- ↑ "DVD Review – 'The Adventures Of Mark Twain' - Collider". Collider. 13 February 2006. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ Lenburg, Jeff (2009). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons (3rd ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8160-6600-1.

- ↑ Albert Bigelow Paine. "Mark Twain, a Biography, Chapter 282 "Personal Memoranda"". Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ↑ Albert Bigelow Paine. "Mark Twain, a Biography, Chapter 293 "The Return to the Invisible"". Archived from the original on September 21, 2019. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Reboy, Joseph A. (May 1988). "Atlantic Releasing saw Mark Twain only as kiddie fodder". Cinemafantastique. Fourth Castle Micromedia. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ↑ Claymation Mark Twain film gets new life on home video - cleveland.com

- ↑ "The Adventures of Mark Twain (1985) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ↑ "The Adventures of Mark Twain Movie Review - Common Sense Media". 10 September 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ↑ MOVIES OF THE '80s : ANIMATION : MICE DREAMS - Los Angeles Times

- ↑ Enchanted Drawings - Google Books (pgs.287-293)