| Ballet of the Nuns | |

|---|---|

Marie Taglioni, 1839 | |

| Choreographer | Filippo Taglioni |

| Music | Giacomo Meyerbeer |

| Libretto | Eugène Scribe |

| Based on | Quarante miracles dits de Notre-Dame |

| Premiere | 22 November 1831 Paris Opéra |

| Original ballet company | Paris Opéra Ballet |

| Characters | Bertram Robert le Diable Helena, an Abbess Ghosts of Nuns |

| Design | Henri Duponchel Pierre Ciceri |

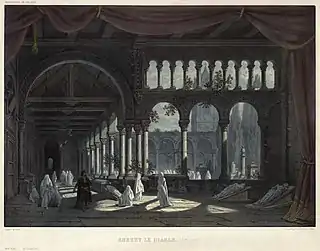

| Setting | Sainte-Rosalie Cloister in ruins |

| Created for | Marie Taglioni |

| Genre | Gothic Romanticism |

| Type | Romantic ballet |

Ballet of the Nuns is the first ballet blanc and the first romantic ballet.[1] It is an episode in Act 3 of Giacomo Meyerbeer's grand opera, Robert le diable. It was first performed in November 1831 at the Paris Opéra. The choreography (now lost) was created by Filippo Taglioni. Jean Coralli may have choreographed the entry of the nuns.[2]

The short ballet tells of deceased nuns rising from their tombs in a ruined cloister. Their aim is to seduce the knight, Robert le Diable, into accepting a talisman to win him a princess. At the end of the ballet, the white-clad nuns return to their tombs. The ballet was created (in part) to demonstrate the building's newly installed gas lighting. The lighting was capable of creating ghastly effects.[3]

Ballet of the Nuns starred Marie Taglioni as the Abbess Helena. Although opening night was marred with a few mishaps, Taglioni made her indelible mark on the ballet world in the role. She became known for her ethereal qualities and her moral purity, and is one of the most celebrated ballerinas in history.[3]

Story

The ballet opens with Bertram, Robert le Diable's father, entering the ruined cloister of Sainte-Rosalie. He summons the ghosts of nuns who have violated their vows. They rise from their graves. He orders them to seduce his son Robert into accepting a deadly talisman. The Abbess Helena orders the ghosts to waltz. In spite of their sacred vows, the nuns waltz. The dead nuns give themselves over to unholy thrills.[4]

Robert enters. The nuns hide, but return to prevent his escape. Robert stands terrified before a saint's tomb. The Abbess lures him towards the talisman in the saint's hand. Robert seizes it. The nuns continue their dance, fluttering like white moths. Their graves open and they sink into the earth. Stone slabs slide into place, covering the dead. A choir of demons is heard.[5]

Background

Ballet of the 18th century was based on rational thought and classical art. The French Revolution however ushered in a period that brought romantic ballet to the stage. Trapdoors, gas lighting, and other elements that became associated with the romantic ballet had been used in the popular theaters on the Paris boulevards for some time. Such elements would gain official sanction and prestige at the Paris Opéra in the middle decades of the 19th century.[3]

A ballet on a Robert le Diable theme was danced in Paris before Her Highness Mlle de Longueville in 1652. Ballet of the Nuns however was something entirely new in concept to audiences on the ballet's opening night. Henri Duponchel, managing director of the Paris Opéra, was in charge of visual effects at the Opéra. He wanted to demonstrate the venue's recently installed gas lighting.[3] Its reflectors produced a stronger, more keenly directed light than ever before. Working with him was Pierre-Luc-Charles Ciceri, chief scenery designer. Ciceri was inspired by either the Saint-Trophime cloister in Arles or the cloister of Monfort-l'Amaury for the ballet's moonlit setting.[2][3]

The theme of the ballet is passion and death, and love beyond the grave. The scene is night rather than day, and Gothic Europe rather than the classical world of Greece and Rome. After almost 100 years of rational thought, audiences were clamoring for the mysterious, the supernatural, the vague, and the doomed. The story of the ballet is about a knight who slips into a cloister at midnight to steal a talisman from a dead saint's hand that will allow him to win a princess.[3]

Hans Christian Andersen included the scene in one of his novels. Andersen writes of the scene, "By the hundred they rise from the graveyard and drift into the cloister. They seem not to touch the earth. Like vaporous images, they glide past one another ... Suddenly their shrouds fall to the ground. They stand in all their voluptuous nakedness, and there begins a bacchanal."[6] The nuns were not completely naked, but Andersen did capture the essence of the scene.[7]

Opening night

Opening night was spoiled by a falling gaslight and a trapdoor that would not close properly. A piece of scenery fell, narrowly missing Taglioni. The curtain was brought down. The ballerina assured everyone she was unharmed. The curtain rose and the performance continued. It ended in a triumph for Meyerbeer, the Taglionis, and Dr. Louis Véron, the Opéra's new manager.[8]

Dr. Véron had recently been awarded the Paris Opéra as a private enterprise. He had great faith in Taglioni. He raised her salary to an unprecedented 30,000 francs a year. Her father was named ballet master with a three-year contract. Véron's boldness was rewarded when Taglioni fulfilled her promise and became a great star.[8]

Reception

The audience took prurient delight in the scandalous Nuns. A reviewer for the Revue des Deux-Mondes wrote:

A crowd of mute shades glides though the arches. All these women cast off their nuns' costume, they shake off the cold powder of the grave; suddenly they throw themselves into the delights of their past life; they dance like bacchantes, they play like lords, they drink like sappers. What a pleasure to see these light women.[9]

Nuns was the first ballet blanc and the first romantic ballet.[1] The opera was performed 756 times between 1831 and 1893 at the Paris Opéra.[1] French Impressionist painter Edgar Degas painted the ballet scene several times between 1871 and 1876.[8]

Under her contract, Taglioni was to appear in Nuns about a dozen times. She left after six. It is possible that the erotic implications of the nuns' ballet did not set well with her. She may have been reluctant to appear in a ballet within an opera. A foot injury and the accidents that marred the first performance may have given the ballerina pause for thought.[2][8] Bad press directed at her father may have caused Taglioni to withdraw.[10] Taglioni was replaced by Louise Fitzjames, who danced the role 232 times.[11]

The Danish choreographer August Bournonville saw Fitzjames's performance as the Abbess in Paris in 1841. He based his own choreography, which was used in Copenhagen between 1843 and 1863, on this. His choreography has been fully preserved. It represents the only record of the original.[12]

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's future wife Fanny Appleton wrote, "The diabolical music and the dead rising from their tombs and the terrible darkness and the strange dance unite to form a stage effect almost unrivaled. The famous witches' (nuns) dance in the freezing moonlight in the ruined abbey, was as impressive as expected ... They drop in like flakes of snow and are certainly very charming witches with their jaunty Parisian figures and most refined pirouettes."[8]

Critic and dance historian Andre Levinson writes, "The academic dance had been an agreeable exercise to watch. Now, [ballet] clarified matters of the soul. Ballet was a divertissement (an entertainment, a distraction). It became a mystery."[8] Kisselgoff writes, "... the preoccupation with the supernatural that characterized so much of 19th-century ballet could be traced to the success of the Ballet of the Nuns in Meyerbeer's first production at the Paris Opéra".[2]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Stoneley 2007, p. 22

- 1 2 3 4 Kisselgoff 1984

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kirstein 1984, p. 142

- ↑ Kirstein 1984, p. 142.

- ↑ Kirstein 1984, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Quoted in Stoneley 2007, pp. 22–23

- ↑ Stoneley 2007, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Quoted in Kirstein 1984, p. 143

- ↑ Cited in Williams 2003, p. 71

- ↑ Guest 2008, p. 205.

- ↑ Jürgenson 1998, p. 76.

- ↑ Jürgenson 1998, pp. 78–79.

References

- Guest, Ivor (2008), The Romantic Ballet in Paris, Dance Books, pp. 201–210, ISBN 978-185273-119-9

- Jürgenson, Knud Arne (1998), The "Ballet of the Nuns" from Robert le diable and its Revival", in Meyerbeer und das europäische Musiktheater, Laaber-Verlag, pp. 73–86, ISBN 3-89007-410-3

- Kirstein, Lincoln (1984), Four Centuries of Ballet : Fifty Masterworks, Dover Publications, Inc., ISBN 0-486-24631-0

- Kisselgoff, Anna (December 2, 1984), "Romantic Ballet began in an Opera by Meyerbeer", The New York Times

- Stoneley, Peter (2007), A Queer History of the Ballet, Routledge, pp. 24–25

- Williams, Simon (2003), The Spectacle of the Past in Grand Opera, in Charlton (2003), pp. 58–75