Robert Henri | |

|---|---|

Robert Henri, 1897 | |

| Born | Robert Henry Cozad June 24, 1865 Cincinnati, Ohio, US |

| Died | July 12, 1929 (aged 64) New York City, US |

| Education | Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Académie Julian, École des Beaux Arts |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Ashcan School |

Robert Henri (/ˈhɛnraɪ/; June 24, 1865 – July 12, 1929) was an American painter and teacher.

As a young man, he studied in Paris, where he identified strongly with the Impressionists, and determined to lead an even more dramatic revolt against American academic art, as reflected by the conservative National Academy of Design. Together with a small team of enthusiastic followers, he pioneered the Ashcan School of American realism, depicting urban life in an uncompromisingly brutalist style. By the time of the Armory Show, America's first large-scale introduction to European Modernism (1913), Henri was mindful that his own representational technique was being made to look dated by new movements such as Cubism, though he was still ready to champion avant-garde painters such as Henri Matisse and Max Weber.

Henri was named as one of the top three living American artists by the Arts Council of New York.

Early life

Robert Henri was born Robert Henry Cozad in Cincinnati, Ohio, to Theresa Gatewood Cozad and John Jackson Cozad, a gambler and real estate developer.[1][2] Henri was a distant cousin of the painter Mary Cassatt.[3] In 1871, Henri's father founded the town of Cozaddale, Ohio. In 1873, the family moved west to Nebraska, where John J. Cozad founded the town of Cozad.[3][4]

In October 1882, Henri's father became embroiled in a dispute with a rancher, Alfred Pearson, over the right to pasture cattle on land claimed by the family. When the dispute turned physical, Cozad shot Pearson fatally with a pistol. Cozad was eventually cleared of wrongdoing, but the mood of the town turned against him. He fled to Denver, Colorado, and the rest of the family followed shortly afterwards. In order to disassociate themselves from the scandal, family members changed their names. The father became known as Richard Henry Lee, and his sons posed as adopted children under the names Frank Southern and Robert Earl Henri (pronounced "hen rye"). In 1883, the family moved to New York City, then to Atlantic City, New Jersey, where the young artist completed his first paintings.[5]

Education

In 1886, Henri enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, where he studied under Thomas Anshutz, a protege of Thomas Eakins, and Thomas Hovenden, who was especially interested in anatomy.[6][7] In 1888, he traveled to Paris to study at the Académie Julian,[8] where he studied under the academic realist William-Adolphe Bouguereau, came to admire greatly the work of Francois Millet, and embraced Impressionism. "His European study had helped Henri develop rather catholic tastes in art."[9] He was admitted into the École des Beaux Arts. He visited Brittany and Italy during this period. At the end of 1891, he returned to Philadelphia, studying under Robert Vonnoh at the Pennsylvania Academy. In 1892, he began teaching at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. "A born teacher, Henri enjoyed immediate success at the school."[10]

Work

In Philadelphia, Henri began to attract a group of followers who met in his studio to discuss art and culture, including several illustrators for the Philadelphia Press who would become known as the "Philadelphia Four": William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and John Sloan. They called themselves the Charcoal Club. Their gatherings featured life drawing, raucous socializing, and readings and discussions of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Émile Zola, Henry David Thoreau, William Morris Hunt, and George Moore.

Ashcan School

By 1895, Henri had come to reconsider his earlier love of Impressionism, calling it a "new academicism." He was urging his friends and proteges to create a new, more realistic art that would speak directly to their own time and experience. He believed that it was the right moment for American painters to seek out fresh, less genteel subjects in the modern American city. The paintings by Henri, Sloan, Glackens, Luks, Shinn, and others of their acquaintance that were inspired by this outlook eventually came to be called the Ashcan School of American art. They spurned academic painting and Impressionism as an art of mere surfaces. Art critic Robert Hughes declared that, "Henri wanted art to be akin to journalism. He wanted paint to be as real as mud, as the clods of horse-shit and snow, that froze on Broadway in the winter, as real a human product as sweat, carrying the unsuppressed smell of human life."[11] Ashcan painters began to attract public attention in the same decade in which the realist fiction of Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser, and Frank Norris was finding its audience and the muckraking journalists were calling attention to slum conditions.[12]

For several years, Henri divided his time between Philadelphia and Paris, where he met the Canadian artist James Wilson Morrice.[13] Morrice introduced Henri to the practice of painting pochades on tiny wood panels that could be carried in a coat pocket along with a small kit of brushes and oil. This method facilitated the kind of spontaneous depictions of urban scenes which would come to be associated with his mature style.

In 1898, Henri married Linda Craige, a student from his private art class. The couple spent the next two years on an extended honeymoon in France, during which time Henri prepared canvases to submit to the Salon.[14] In 1899 he exhibited "Woman in Manteau" and La Neige ("The Snow"), which was purchased by the French government for display in the Musée du Luxembourg.[15] He taught at the Veltin School for Girls beginning in 1900[16] and at the New York School of Art from 1902, where his students included Joseph Stella, Edward Hopper and his future wife Josephine Nivison, Rockwell Kent, George Bellows, Norman Raeben, Louis D. Fancher, and Stuart Davis. In 1905, Linda, long in poor health, died.[15] Three years later, Henri remarried; his new wife, Marjorie Organ, was a twenty-two-year-old cartoonist for the New York Journal.[17] (Henri's 1911 portrait of Marjorie, The Masquerade Dress, is one of his most famous paintings and hangs in the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

In 1906, Henri was elected to the National Academy of Design, but when painters in his circle were rejected for the academy's 1907 exhibition, he accused fellow jurors of bias and walked off the jury, resolving to organize a show of his own. He would later refer to the academy as "a cemetery of art."

The Eight

In 1908, Henri was one of the organizers of a landmark show entitled "The Eight" (after the eight painters displaying their works) at the Macbeth Galleries in New York. Besides his own works and those produced by the "Philadelphia Four" (who had followed Henri to New York by this time), three other artists who painted in a different, less realistic style—Maurice Prendergast, Ernest Lawson, and Arthur B. Davies—were included. The exhibition was intended as a protest against the exhibition policies and narrowness of taste of the National Academy of Design. The show later traveled to several cities from Newark to Chicago, prompting further discussion in the press about the revolt against academic art and the new ideas about acceptable subject matter in painting.

Henri was, by this point, at the heart of the group who argued for the depiction of urban life at its toughest and most exuberant. Conservative tastes were necessarily affronted. About Henri's Salome of 1909, critic Hughes observed: "Her long legs thrust out with strutting sexual arrogance and glint through the over-brushed back veil. It has far more oomph than hundreds of virginal, genteel muses, painted by American academics. He has given it urgency with slashing brush marks and strong tonal contrasts. He's learned from Winslow Homer, from Édouard Manet, and from the vulgarity of Frans Hals".[18]

In 1910, with the help of John Sloan and Walt Kuhn, Henri organized the Exhibition of The Independent Artists, the first nonjuried, no-prize show in the U.S., which he modeled after the Salon des Indépendants in France. Works were hung alphabetically to emphasize an egalitarian philosophy. The exhibition was very well-attended but resulted in few sales.[19] The relationship between Henri and Sloan, both believers in Ashcan realism, was a close and productive one at this time; Kuhn would play a key role in the 1913 Armory Show. Biographer William Innes Homer writes: "Henri's emphasis on freedom and independence in art [as demonstrated in the Exhibition of Independent Artists], his rebuttal of everything the National Academy stood for, makes him the ideological father of the Armory Show."[20]

Two more shows were organized in 1911 and 1912.[21]

The Armory Show, American's first large-scale introduction to European Modernism, was a mixed experience for Henri. He exhibited five paintings but, as a representational artist, he naturally understood that Cubism, Fauvism, and Futurism implied a challenge to his style of picture-making. In fact, he had cause to be worried. A man, not yet fifty, who saw himself in a vanguard was about to be relegated to the position of a conservative whose day had passed. Arthur B. Davies, an organizer of the show and a member of The Eight, was particularly disdainful of Henri's concern that the new European art would overshadow the work of American artists. On the other hand, some Henri scholars have insisted that the reputation Henri earned in later histories as an opponent of the Armory Show and of Modernism in general is unfair and vastly overstates his objections.[22] They point out that he had a keen interest in new art and recommended that his students avail themselves of opportunities to study it.[23] Art historian Sarah Vure notes that "[as] early as 1910, Henri advised students to attend an exhibition of works by Henri Matisse and two years later he urged them to see the work of Max Weber, one of the most avant-garde of American moderns." He urged painter Charles Sheeler to visit the Albert C. Barnes collection of modern art in Pennsylvania.[24]

Never a conservative politically, Henri admired anarchist and Mother Earth publisher Emma Goldman and taught from 1911 at the Modern School. Goldman, who later sat for a portrait by Henri, described him as "an anarchist in his conception of art and its relation to life."[25]

Ireland and Santa Fe

.jpg.webp)

Henri made several trips to Ireland's western coast and rented Corrymore House near Dooagh, a small village on Achill Island, in 1913. Every spring and summer for the following years he would paint the children of Dooagh. Henri's portraits of children, seen today as the most sentimental aspect of his body of work, were popular at the time and sold well. In 1924, he purchased Corrymore House.[26] During the summers of 1916, 1917 and 1922, Henri went to Santa Fe, New Mexico to paint. He found that locale as inspirational as the countryside of Ireland had been. He became an important figure in the Santa Fe art scene and persuaded the director of the state art museum to adopt an open-door exhibition policy. He also persuaded fellow artists George Bellows, Leon Kroll, John Sloan and Randall Davey to come to Santa Fe.[27] In 1918 he was elected as an associate member of the Taos Society of Artists.[28]

Death and burial

While traveling to the United States after visiting his summer home in Ireland in November 1928, Robert Henri suffered an attack of neuritis, which crippled his leg. The underlying cause was metastatic prostate cancer.[29] He was hospitalized at St. Luke's Hospital in New York. Gradually he became weaker, until he died of cardiac arrest early in the morning of July 12, 1929. His illness was not generally known, and came as a surprise in art circles.[30] Upon his death, artist and pupil Eugene Speicher said "not only was he a great painter, but ... I don't think it too much to call him the father of independent painting in this country."[30] At his death, it was reported that he was cremated, and his ashes buried in the family vault in Philadelphia.[31][lower-alpha 1]

Influence and legacy

From 1915 to 1927, Henri was a popular and influential teacher at the Art Students League of New York. "He gave his students, not a style (though some imitated him), but an attitude, an approach, [to art]."[34] He also lectured frequently about the theories of Hardesty Maratta, Denham Waldo Ross, and Jay Hambidge.[35] (Henri's interest in these men, whose ideas were in fashion at the time but were not taken seriously later, has proved to be "the most misunderstood aspect of [Henri's] pedagogy").[36] Maratta and Ross were color theorists (Maratta manufactured his own system of synthetic pigments), while Hambidge was the author of an elaborate treatise, Dynamic Symmetry, that argued for a scientific basis for composition. Henri's philosophical and practical musings were collected by former pupil Margery Ryerson and published as The Art Spirit (1923), a book that remained in print for several decades. Henri's other students include George Bellows, Arnold Franz Brasz, Stuart Davis, Edward Hopper, Rockwell Kent, Henry Ives Cobb, Jr., Lillian Cotton, Amy Londoner, John Sloan, Minerva Teichert,[37][38] Peppino Mangravite, Rufus J. Dryer, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and Mabel Killam Day.

The significance and often formative influence of Henri as a teacher and mentor to women artists was acknowledged in American Women Modernists: The Legacy of Robert Henri (2005). Comparing the work of Henri's female students to their male Ashcan School contemporaries, Marion Wardle asserts, "An examination of their experiments in many media illuminates a much broader application of Henri's modernist ideals. ...Henri's women students contributed significantly to the structure of American modernism. They produced a large body of work, exhibited widely, won major art awards, belonged to and administered arts organizations, and taught art classes across America."[39]

In the spring of 1929, Henri was named as one of the top three living American artists by the Arts Council of New York. Henri died of cancer that summer at the age of sixty-four. He was eulogized by colleagues and former students and was honored with a memorial exhibition of seventy-eight paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Forbes Watson, editor of The Arts magazine wrote, "Henri, quite aside from his extraordinary personal charm, was an epoch-making man in the development of American art."[40]

Fittingly, among Henri's most enduring works are his portraits of his fellow painters. His 1904 full-length portrait of George Luks (in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa)[41] and his 1904 portrait of John Sloan (in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, formerly in the collection of The Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.),[42] for example, exhibit all the classic elements of his style: forceful brushwork, intense (if dark) color effects, evocation of personality (his and the sitter's), and generosity of spirit.

The Robert Henri Museum in Cozad, Nebraska occupies one of Henri's former homes and focuses on his work.

The National Arts Club in New York City is home to the Robert Henri Library which includes artwork and a number of scrapbooks belonging to Henri. The Library is made available to qualifying scholars and professionals. Henri became an Artist Life Member of the Club in 1913.

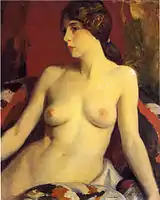

Gallery

Portrait of Carl Gustav Waldeck, 1896, Robert Henri Museum

Portrait of Carl Gustav Waldeck, 1896, Robert Henri Museum Woman in Manteau, 1898, Brooklyn Museum

Woman in Manteau, 1898, Brooklyn Museum The Blue Kimono, 1909, New Orleans Museum of Art

The Blue Kimono, 1909, New Orleans Museum of Art The Dancer, 1910

The Dancer, 1910 Dutch Girl, 1910 (photograph from 1910)

Dutch Girl, 1910 (photograph from 1910) Figure in Motion, 1913

Figure in Motion, 1913 Mildred Clarke von Kienbusch, 1914, Princeton University Art Museum

Mildred Clarke von Kienbusch, 1914, Princeton University Art Museum Tam Gan, 1914, Albright-Knox Art Gallery

Tam Gan, 1914, Albright-Knox Art Gallery The Beach Hat, 1914, oil on canvas, The Detroit Institute of Arts

The Beach Hat, 1914, oil on canvas, The Detroit Institute of Arts Edna Smith in a Japanese Wrap, 1915, Indianapolis Museum of Art

Edna Smith in a Japanese Wrap, 1915, Indianapolis Museum of Art

Portrait of Fay Bainter, 1918

Portrait of Fay Bainter, 1918 Mata Moana, 1920

Mata Moana, 1920 Bernardita, 1922

Bernardita, 1922 Portrait of Eugenie Stein, 1906/1907, The National Arts Club

Portrait of Eugenie Stein, 1906/1907, The National Arts Club

Bibliography

- Henri, Robert (2007) [1923]. The Art Spirit. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-06-430138-1.

Notes

- ↑ There is also a listing for Robert Henri (along with Richard and Theresa Lee) in the database of Providence, Rhode Island's Swan Point Cemetery.[32] A 1957 AP news story suggests that Henri's father John Cozad/Richard Lee was disinterred and reburied in Rhode Island.[33]

References

Citations

- ↑ Homer (1969).

- ↑ Perlman (1991).

- 1 2 Perlman (1991), p. 1.

- ↑ Henshaw (1957): "Cozad, Nebraska, finally has found its founder after, lo, these many moons."

- ↑ Homer (1969), p. 7.

- ↑ "Robert Henri". Retrieved August 17, 2022.

- ↑ Homer (1969), pp. 25–27.

- ↑ oxfordindex.oup.com

- ↑ Homer (1969), p. 65.

- ↑ Homer (1969), p. 71.

- ↑ Hughes, Robert (February 5, 2002). "The Wave from the Atlantic". American Visions. Episode 5 of 8. BBC.

- ↑ Hunter (1959), pp. 28–40.

- ↑ Homer (1969), p. 86.

- ↑ Homer (1969), pp. 90–94.

- 1 2 Homer (1969), p. 119.

- ↑ Bennard B. Perlman; Arthur Bowen Davies (1998). The Lives, Loves, and Art of Arthur B. Davies. SUNY Press. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-0-7914-3835-0.

- ↑ Homer (1969), p. 146.

- ↑ Hughes (1997), p. 325.

- ↑ Homer (1969), pp. 152–156.

- ↑ Homer (1969), p. 155.

- ↑ Levin, Gail. Edward Hopper an intimate biography.

- ↑ Rose (1975) refers to Henri as "blind and hostile" to Picasso and Matisse (p. 30).

- ↑ Homer (1969), p. 174.

- ↑ Vure (2009), p. 57.

- ↑ Goldman, Emma (1931). "Chapter 40". Living My Life. Vol. two. New York: Alfred A Knopf Inc. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ↑ Perlman (1991), p. 133.

- ↑ Leeds, Valerie Anne (1998). Robert Henri in Santa Fe : His Work and Influence. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Gerald Peters Gallery. ISBN 0935037837.

- ↑ White, Robert R. (1998). The Taos Society of Artists. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. ISBN 0826319467.

- ↑ Perlman (1991), p. 135.

- 1 2 "Robert Henri Dies; Ill Eight Months" (PDF). The New York Times. July 13, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

Robert Henri, eminent American artist, died early yesterday morning at St. Luke's Hospital. Although he had been a patient at the institution since November, his illness was not generally known and his death came as a surprise to art circles.

- ↑ "Robert Henri's Funeral" (PDF). The New York Times. July 14, 1929. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

The ashes will be buried in the family vault at Philadelphia this week.

- ↑ "Burial Information". Swan Point Cemetery. Retrieved April 16, 2015.

- ↑ Henshaw (1957): "Lee-Cozad died (with his boots off of pneumonia) in New York City in 1906. He was buried in Pleasantville, NJ. Later his remains were disinterred and reburied in Providence, RI."

- ↑ Homer (1969), p. 269.

- ↑ Homer (1969), pp. 184–194.

- ↑ Vure (2009), p. 60.

- ↑ Jan Underwood Pinborough, Minerva Kohlhepp Teichert: With a Bold Brush

- ↑ Wardle (2005), p. 206.

- ↑ Wardle (2005), p. 4.

- ↑ Homer (1969), p. 209.

- ↑ "Robert Henri, George Luks (1904)". Retrieved September 26, 2023.

- ↑ Henri, Robert (1904), John Sloan, retrieved September 26, 2023

Sources

- Goodman, Helen. "Robert Henri, Teacher." Arts Magazine, September 1979, pp. 158–160.

- Henshaw, Tom (April 28, 1957). "Man Behind the Name: Mystery of Cozad is Finally Broken". The Lincoln Star. Lincoln, Nebraska. Associated Press. p. 35.

- Homer, William Innes (1969). Robert Henri and his Circle. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0878173269.

- Hughes, Robert (1997). American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America. New York: Knopf. ISBN 0676527841.

- Hunter, Sam (1959). Modern American Painting and Sculpture. New York: Dell.

- Perlman, Bennard (1991). Robert Henri: His Life and Art. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0486267229.

- Rose, Barbara (1975). American Art Since 1900. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 050020067X.

- Vure, Sarah (2009). "After the Armory: Robert Henri, Individualism and American Modernisms". In Kennedy Elizabeth (ed.). The Eight and American Modernisms. Chicago: Terra Foundation For American Art. ISBN 978-0932171566.

- Wardle, Marian, ed. (2005). American Women Modernists: The Legacy of Robert Henri, 1910–1945. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813536839.

Further reading

- Brown, Milton W. (1955). American Painting from the Armory Show to the Depression. Princeton: Princeton University Press. OCLC 2310948.

- Leeds, Valerie Ann (1994). My People: The Portraits of Robert Henri. Orlando, FL: Orlando Museum of Art. ISBN 1-880699-03-6.

- Leeds, Valerie Ann (2005). Robert Henri: The Painted Spirit. New York: Gerald Peters Gallery. ISBN 1-931717-15-X.

- Leeds, Valerie Ann; Stuhlman, Jonathan (2011). From New York to Corrymore: Robert Henri and Ireland. Charlotte, NC: Mint Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-9762300-9-0.

- Leeds, Valerie Ann (2013). Spanish Sojourns: Robert Henri and the Spirit of Spain. Savannah, GA: Telfair Museums. ISBN 978-0-933075-20-7.

- Nicoll, Jessica F. (1995). The Allure of the Maine Coast: Robert Henri and His Circle, 1903–1918. Portland, ME: Portland Museum of Art. ISBN 0-916857-07-7.

- Perlman, Bennard, ed. (1997). Revolutionaries of Realism: The Letters of John Sloan and Robert Henri. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691044132.

External links

- Robert Henri exhibition catalogs (full pdf) from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries

- Robert Henri Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.