| |

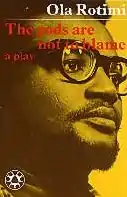

| Author | Ola Rotimi |

|---|---|

| Country | Nigeria |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Play |

| Publisher | Oxford University Press Oxford, University Press plc (UPPLC) |

Publication date | 1971 |

| Media type | Print (Paperback) |

| Pages | 72 pp |

| ISBN | 0-19-211358-5 |

| Preceded by | Our Husband Has Gone Mad Again |

| Followed by | Kurunmi |

The Gods Are Not To Blame is a 1968 play and a 1971 novel by Ola Rotimi.[1] An adaptation of the Greek classic Oedipus Rex, the story centres on Odewale, who is lured into a false sense of security, only to somehow get caught up in a somewhat consanguineous trail of events by the gods of the land.[2]

The novel is set in an indeterminate period of a Yoruba kingdom. This reworking of Oedipus Rex was part of the African Arts (Arts d'Afrique) playwriting contest in 1969. Rotimi's play has been celebrated on two counts: at first scintillating as theatre and later accruing a significant literary aura.[3] This article focuses specifically on the 1968 play.

Characters

Odewale: The king of Kutuje, who had risen to power by unknowingly murdering the old king, King Adetusa, whom, also not to his knowledge, was his father. The manner in which he kills his father is revealed in a flashback when his childhood friend, Alaka, comes to Kutuje to ask him why he was not in the village of Ede as he said he would be when he departed at age thirteen. Similar in nature to the Greek play, Oedipus Tyrannus his royal parents receive a prophecy from Baba Fakunle that Odewale would grow up to kill his parents. To prevent this from occurring, King Adetusa orders for Odewale to be killed. Instead, he is wrapped in a white cloth (symbolizing death) and left in a bush far from Kutuje. He is found and picked up by a farmer hunter Ogundele and raised by him along with his wife Mobe. Odewale is confronted by Gbonka, a messenger, who tells of the event that lead to King Adetusa's end. Along with the Ogun Priest, it is revealed to him that the old king was his father, and that Ojuola was his mother.

Ojuola: Wife of the late King Adetusa. Current wife of King Odewale. She is the mother of six children: two under King Adetusa (Odewale and Aderepo), and four under King Odewale (Adewale, Adebisi, Oyeyemi, Adeyinka). She was given a prophecy, along with King Adetusa, that their child, Odewale, would one day grow up to usurp the thrown, killing his father and marry his mother. As the queen of the kingdom of Kutuje, she finds herself serving as Odewale's conscience, calming him when he begins to act irrationally. When it is revealed by the Ogun Priest that Ojuola is, in fact, Odewale's mother, she goes to her bedroom and kills herself.

Aderopo: Brother of Odewale, and son of King Adetusa and Ojuola. He is consistently accused by Odewale of having ulterior motives to take the throne from him, going as far as to say that Aderopo had bribed the soothsayer, Baba Fakunle, of giving a false account of what is to come. Aderopo is also accused of spreading the rumor that Odewale was the one who murdered the old king, Adetusa.

King Adetusa: Former king of Kutuje. Despite his best efforts to curb the prophecy that his child, Odewale, would grow up to take the throne by murdering him, he is inevitably slain when he encounters his son, now fully grown, in the village of Ede.

Baba Fakunle: A blind, old man, Baba Fakunle serves as a soothsayer to those who seek him. He is summoned by Odewale to ask of a way to rid the suffering of his kingdom. Baba Fakunle tells him that the source of the kingdom's ails lay with him. After a dispute, Baba Fakunle calls Odewale a "murderer," alluding to the assault that occurred on the yam patch in Ede, in which Odewale kills King Adetusa, unknowingly his father.

Alaka: Odewale's childhood friend. Alaka hails from the village of Ishokun. He comes to Kutuje to tell Odewale that the man he called father had passed two years prior and that his mother, though old, was still in good health. It is during the course of the play that Odewale reveals to Alaka why it was that he left the village of Ede, where Odewale said he would live after leaving Ishokun when he was thirteen.

Gbonka: The former messenger of the late King Adetusa. Gbonka was present when King Adetusa was slain at the hands of Odewale. Near the play's end, Gbonka retells this event to Odewale, which leads to the discovery that Odewale was in fact the son of the former king, and the son of the current queen, and his birth mother, Ojuola.

Plot

Number of Acts and Scenes The play consists of three acts and ten scenes as follows;

Act 1 : 2 scenes

Act 2 : 4 scenes

Act 3 : 4 scenes

Prologue

Ola Rotimi's The Gods Are Not To Blame is the series of unfortunate events that occur in King Odewale's life. Rotimi seals Odewale's fate by having an omen placed over his life at birth. Odewale's horrible fate, whether it had been the Seer being silent, or even his parents not ordering his death.

Act I

Odewale storms Kutuje with his chiefs flanking by his side, and is declared King by the town's first chief. The King expresses sympathy to the townspeople for the illness that has been plaguing them. He brings his sick children for the town to see, that way they know that his family is also suffering. Aderopo gives good news to Odewale from Orunmila concerning the sickness going around the kingdom, but along with the good news comes the bad. Odewale learns that there is a curse on the land, and in order for the sickness to stop going around the curse has to be purged. Odewale finds out that the man who is cursed killed King Adetusa I.

Act II

The village elders gather round to discuss the allegations that have been made against Odewale. A blind soothsayer, Baba Fakunle, is brought in to share with Odewale the murderer of the old king. Odewale begins to make accusations of a plot being made against him, spearheaded by Aderopo, to one of the village chiefs in response to Baba Fakunle's silence. Aderopo arrives and is immediately confronted by Odewale about his suspicions. Aderopo denies the allegations, and Odewale calls forth the Priest of Ogun. Odewale banishes Aderopo from the kingdom.

Act III

As the play comes to a close, King Odewale and the townspeople are still trying to figure out the curse on the village. At this point we are introduced to Alaka, who claims to have known King Odewale since before he came to conquer Kutuje. Odewale confesses that his life spiraled out of control when he killed a man. Later, Ojuola explains that Baba Fakunle made her kill her first born son, convinced that her first son had brought bad luck. Odewale says to the land that the biggest trouble today is not their sickness but instead the plague in their hearts. In the last part Odewale leaves. Odewale brings real facts to the people of the land. Odewale closes the play by stating, ″the gods have lied″ Nathaniel.

Theme and motifs

African symbolism

In The God’s Are Not To Blame, Rotimi incorporates many themes, such as culture and its connection with the form of the social structure of an African community. The culture represents "the way of life for an entire society", as noted in Pragmatic Functions of Crisis – Motivated Proverbs in Ola Rotimi's The Gods Are Not to Blame. All the messages conveyed, although bring the play together and provide the audience with insightful readings, the play may also serve as a symbol as to how some of the African societies model the structure presented in the play. The practices exhibited in Yoruban culture show the structure of both a social and economical factors. The leadership in the play forms a comparison to that of the King and many of the townspeople. One finds that their roles compared to King Odewale's serve as a primary example of the social aspect. In the economic structure, one observes the resources the Yoruban culture considers vital to maintain wellness and health. During their time of sickness, the townspeople solely depend on the herbs used as an attempt to cure the "curse" put on the people.

Yoruba culture and influences

The Gods Are Not to Blame is influenced by Yoruba and Yoruban culture. Ola Rotimi had an immense knowledge and interest in African cultures, as indicated in his ability to speak several ethnic languages, such as Yoruba, Ijaw, Hausa, and pidgin.[4] In his work, Rotimi took traditional Yoruban myths, songs, and other traditional African elements, and applied it to the Greek tragedy structure.

The comical character Alaka, for example, represents Odewale's childhood growing up in the village of Ishokun. Ishokun, in the play, is a small farming village, wherein Odewale learned to harvest yams. By juxtaposing Alaka in Odewale's new environment, Kutuje, Rotimi illustrates the cultural differences between traditional Yoruban life, with that of the industrialized west. Rotimi, in response to the Nigerian Civil War, says that the root cause of the strife among Nigerians, of the bloodshed, was in their lingering mutual ethnic distrust which culminate in open hostility.[5] He says that in post-colonial Africa, much of the blame over the suffering incurred by native Africans was the result of the colonial powers. To this Rotimi argues that while some of the suffering may have been the result of attempted colonial conquests, the lingering animosity that is felt and dispersed among fellow Nigerians, by fellow Nigerians, cannot be blamed solely on an outside party. He felt that the future of Nigerian culture cannot continue to be blamed forces from the past, much like Odewale would blame the suffering of his people, in his kingdom, on the sins of the old king, Adetusa.

Yoruba theory

The Gods Are Not To Blame reflects critically on perhaps the most cherished myth of cultural transmission that civilization entertains about itself as a means of explaining its own perpetuation. Rotimi's play does so not only by dramatizing this myth with certain ironic instance, but also by juxtaposing this myth with a Yoruba model of cultural transmission.[nb 1]

Colonization

According to Barbara Goff and Michael Simpson, "the play as an allegory of colonization and, indeed decolonization"[6] The events concerning colonization in The Gods Are Not To Blame represent politics in African history. When the old man takes over Odewale's land it is a metaphor of colonialism. It's about having power over the land and Odewale no longer has the power because the old man took it from him, which is why he turns a hoe, which is a gardening tool, into a sword. The old man happens to also be his father, though Odewale is not aware of this at the time. His father does to Odewale what European colonizers did to Africa.

Language

The use of myths with dances in the play. Akin Odebunmi in Motivated Proverbs In Ola Rotimi's "The Gods Are Not To Blame" uses myths and dances established in Yoruban culture that helps serve as the basis of the play. Some aspects of the sociocultural and linguistic problems of teaching English to students of one of Nigeria's major language groups"[7]

[8] Odebunmi" Language,Culture and Proverbs". Simply suggest, the use of language is part of culture. Indeed, culture is the way of life.

Scholar Odebunmi says, the concept of this is to understand referring to the actual context of a word said in a play (dialogue) has developed similarities with speech and how it works in culture. In the Yoruban culture, like many others, have symbolic. Odebunmi (2008) then says, language, therefore, expresses the patterns and structures of culture, and consequently influences human thinking, manners and judgement. I believe this scholar is claiming to the idea that proverbs deal with issues in the Yoruban culture. Adewale a character in the play, as Ola Romiti explains in The Gods Are Not To Blame adds that was used for functional means......

Performances and renewed interest

The Gods Are Not To Blame made its début in Nigeria in 1968. The play was revived by Talawa Theatre Company in a well received production in 1989, sparking interest in the play's themes.[9][10] It was nominated for an award at the ESB Dublin Fringe Festival 2003. It was launched again in February 2004, Bisi Adigun and Jimmy Fay's Arambe Productions presenting what Roddy Doyle described as an exhilarating and exciting version of the play to the O'Reilly Theatre.[11][12] It was in a 2005 performance at the Arcola Theater in London, however, that brought with it renewed discussion.[13]

Notes

- ↑ Barbara Goff and Michael Simpson 2007: c2 92-93

References

- ↑ Dictionary of Literary Biography Complete Online Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine: Emmanuel Gladstone Olawale Rotimi|E.G.O (ed 2009) Gale Research

- ↑ "Preview: The Gods Are Not To Blame, Arcola Theatre, London". The Independent. May 26, 2005. Archived from the original on June 12, 2011. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ↑ Barbara Goff and Michael Simpson, Crossroads in the Black Aegean: Oedipus, Antigone, and dramas of the African diaspora, Oxford University Press, United States, 2006 ISBN 0-19-921718-1

- ↑ Akefor, Chinyere. "Ola Rotimi: The Man, The Playwright, and the Producer on the Nigerian Theater Scene", World Literature Today 64.1 (1990): 24-29. Print.

- ↑ Barbara, Goff. "Back to the Motherland: Ola Rotimi's The Gods Are Not to Blame" , Crossroads in the Black Aegean, Oxford University Press, 2008. 84. Print.

- ↑ Goff, Barbara & Simpson, Michael, “Back to the Motherland: Crossroads In The Black Aegean” (97).

- ↑ Odebunmi, Akin. Pragmatic Functions of Crisis – Motivated Proverbs in Ola Rotimi's The Gods Are Not to Blame. Ibadan, January 2008. Retrieved 2008-9-1.

- ↑ "Proverbs deal with issues that border on the values, norms, institutions and artifacts of a society across the whole gamut of the people's experiences. Two examples of the way proverbs do this can be cited from the Yoruba culture"

- ↑ "The Gods Are Not to Blame".

- ↑ "Item Details".

- ↑ Arambe Productions, The Gods Are Not To Blame, O’Reilly Theatre, Belvedere College, Dublin, Ireland, February 2004. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ↑ O’Reilly Theatre, The Gods Are Not To Blame Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Main Auditorium, Belvedere College, Dublin, Ireland, 7–14 February 2004. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ↑ Barbara, Goff. "Back to the Motherland: Ola Rotimi's The Gods Are Not to Blame." Crossroads in the Black Aegean. Oxford UP, 2008. 79. Print.

Further reading

- Martin Owusu, Drama of the Gods: A study of seven African plays, Omenana, Roxbury, Massachusetts, 1983 ISBN 0-685-06783-1

External links

- "The Gods Are Not to Blame.", eNotes.com, 2006. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- Bookrags Staff, (Emmanuel) (Gladstone) Ola(wale) Rotimi, 2005. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- BBC World Drama: Stages of Independence - A celebration of 50 years of African drama, BBC World Service, broadcast 16, 17 October 2010. Retrieved 2011-03-09.